Proyecto, Progreso, Arquitectura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Brochure

TO LET NEW BUILD INDUSTRIAL UNIT COMPUTER GENERATED ILLUSTRATION 23,069 SQ FT 2,143.2 sq m Indicative cgi of finished scheme WILLIAMS BMW A565 GREAT MERCEDES BENZ HOWARD STREET LEEDS PALL STREET MALL PUMPFIELDS ROAD 30% site cover Liverpool City fringe location 2 no. level access loading doors 3 phase electricity supply 0.3 acres – potential external storage or additional car parking 25m 25m turning circle TO LET NEW BUILD INDUSTRIAL UNIT 8m minimum eaves height to underside of haunch 23,069 SQ FT 2,143.2 sq m First floor offices extending to 1,600 sq ft 47 car parking space (including 5 disabled) 10% translucent rooflights 50KN/m2 loading Offices 53.8m 125KVA and mains gas 39.3 m masterplan B1, B2 & B8 Planning 1.75 acre site equating to a low site cover of c. 30% 0.3 acres of expansion land which could be used for additional 25m car parking or external storage 26.4m terms Pumpfields Road The property is available To Let on terms to be agreed. vat Chargeable where applicable at the prevailing rate. 31 7 LYTHAM 6 ST ANNES PRESTON BLACKBURN location 30 RIVER 29 9 2 RIBBLE 1 3 4 Central 23 is located in a prominent position on Carruthers Street, off Pumpfield Road and is a few metres from the junction with the A5038 Vauxhall Road. The LIVERPOOL RAWTENSTALL LEYLAND M65 ECHO ARENA ROYAL ALBERT 28 DARWEN DOCK site sits just 0.5 miles from Liverpool City Centre and only 15 minutes (4.6 miles) LIVERPOOL ONE from the M62 motorway. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Hotel Futures 2014

LIVERPOOL HOTEL FUTURES 2014 Final Report Prepared for: Liverpool Hotel Development Group July 2014 Liverpool Hotel Futures 2014 – Final Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................... i 1.INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES ........................................................................... 1 1.2 RESEARCH AND CONSULTATIONS UNDERTAKEN ...................................................... 2 1.3 REPORT STRUCTURE .............................................................................................. 3 2.LIVERPOOL HOTEL SUPPLY TRENDS.............................................................................. 4 2.1 CHANGES IN LIVERPOOL HOTEL SUPPLY 2004-2014 .............................................. 4 2.2. HOTEL SUPPLY PIPELINE AND FUTURE PROPOSALS .................................................. 12 2.3. INVESTMENT IN EXISTING HOTELS .......................................................................... 14 2.4. COMPARATOR CITY BENCHMARKING ................................................................. 16 2.5. NATIONAL HOTEL DEVELOPMENT TRENDS IN UK CITIES .......................................... 26 2.6. TARGET HOTEL BRANDS FOR LIVERPOOL .............................................................. 32 3.LIVERPOOL -

Industrial Units to Let from 4,364 to 35,000 Sq Ft

MERSEYSIDE, CH41 7ED Industrial Units To Let from 4,364 to 35,000 sq ft • Flexible terms • Fully secure site • Strategically located • Located less than 1 mile to J2 M53 • extensively refurbished Description Junction One Business Park comprises • Steel portal frame The site also benefits from secure of a fully enclosed industrial estate, • Service yards palisade fencing to its entire perimeter, made up of 24 units. • Pitched roofs a barrier entry and exit system with security gatehouse, CCTV coverage • Loading doors Providing a range of unit sizes. over the entire estate and 24 hour • Metal sheet cladding security. • Separate car parking • Level access loading door Industrial Units To Let from 4,364 to 35,000 sq ft HOME DESCRIPTION AERIALs LOCATION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION LIVERPOOL JOHN LENNON AIRPORT LIVERPOOL CITY CENTRE CAMMELL LAIRD STENA LINE BIRKENHEAD RIVER MERSEY KINGSWAY MERSEY TUNNEL BIRKENHEAD DOCKS BIRKENHEAD NORTH RAILWAY STATION click to see AERIAL 2 Industrial Units To Let from 4,364 to 35,000 sq ft HOME DESCRIPTION AERIALsAERIALS LOCATION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION TO WIRRAL & M56 junction 1 m53 TO MERSEY TUNNEL & DOCKS WIRRAL TENNIS & junction 1 retail park A553 SPORTS CENTRE tesco click to see AERIAL 1 Industrial Units To Let from 4,364 to 35,000 sq ft HOME DESCRIPTION AERIALsAERIALS LOCATION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION Ormskirk 5 CK ROAD M61 DO M58 4 SEY 3 4 LA A 5 AL 51 26 3 9 W 39 13 W A5 AL Walkden L 1 ES 14 EY KIN D GSWAY TUN A 25 O NEL APPR 5 CK OAC 0 7 A580 L H 2 -

Mersey Tunnels Long Term Operations & Maintenance

Mersey Tunnels Long Term Operations & Maintenance Strategy Contents Background ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Strategic Overview .................................................................................................................................. 2 Supporting Economic Regeneration ................................................................................................... 3 Key Route Network ............................................................................................................................. 6 National Tolling Policy ......................................................................................................................... 8 Legislative Context .................................................................................................................................. 9 Mersey Crossing Demand ..................................................................................................................... 12 Network Resilience ........................................................................................................................... 14 Future Demand ................................................................................................................................. 14 Tunnel Operations ................................................................................................................................ 17 Supporting Infrastructure -

Lupts 60 Programme

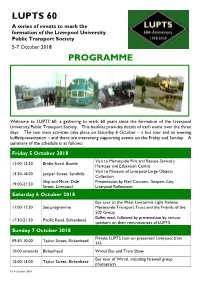

LUPTS 60 A series of events to mark the formation of the Liverpool University Public Transport Society 5-7 October 2018 PROGRAMME Welcome to LUPTS 60, a gathering to mark 60 years since the formation of the Liverpool University Public Transport Society. This booklet provides details of each event over the three days. The two main activities take place on Saturday 6 October – a bus tour and an evening buffet/presentation – and there are interesting supporting events on the Friday and Sunday. A summary of the schedule is as follows: Friday 5 October 2018 Visit to Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service’s 11:00-12:30 Bridle Road, Bootle Heritage and Education Centre Visit to Museum of Liverpool Large Objects 13:30-16:00 Juniper Street, Sandhills Collection Ship and Mitre, Dale Presentation by Neil Cossons: ‘Seaport City: 19:00-21:30 Street, Liverpool Liverpool Reflections’ Saturday 6 October 2018 Bus tour to the West Lancashire Light Railway, 11:00-17:30 See programme Merseyside Transport Trust and the Friends of the 502 Group Buffet meal, followed by presentation by various 17:30-21:30 Pacific Road, Birkenhead speakers on their reminiscences of LUPTS Sunday 7 October 2018 Private LUPTS tour on preserved Liverpool tram 09:30-10:00 Taylor Street, Birkenhead 245 10:00 onwards Birkenhead Wirral Bus and Tram Show Bus tour of Wirral, including farewell group 12:00-13:00 Taylor Street, Birkenhead photograph v2: 4 October 2018 Details of each of the events are given in the succeeding pages. The programme is subject to last minute change, particularly on availability of vehicles. -

Arrowe Brook Park

Arrowe Brook Park A collection of 3 and 4 bedroom homes Arrowe Brook Park Arrowe Brook Road Wirral CH49 1SX Telephone: 0151-391 9881 www.bellway.co.uk Bellway is delighted to welcome Built across a range of styles to Bring together you to Arrowe Brook Park, a the exacting Bellway standard, collection of 3 and 4-bedroom these beautiful new homes convenience, homes in Wirral, boasting a present a variety of features such sought-after location close to as open plan living spaces and countryside both countryside and coast. en suite bathrooms, created for Good shopping facilities, well- modern living. Arrowe Brook and coast regarded local schools and Park is an ideal setting for traditional village amenities are all families, first-time buyers and close to home whilst both commuters alike. Liverpool and the coastal town of West Kirby are within easy reach. Choose a fine quality of life at Arrowe Brook Park Transport connections in the area are excellent Boasting a desirable location, this attractive new with convenient commuter links to surrounding development is well-placed to explore the outdoors. cities and local towns. The site is just 1.6 miles Opposite the development is an area of public green from J3 of the M53, connecting with Liverpool via space which leads directly onto the impressive Arrowe the Kingsway Tunnel (toll £1.80) to the north and Country Park and Golf Club. Spanning 250-acres of with the main motorway network (via the M56) open space and woodland, the park offers numerous waterside walking routes, designated areas for outdoor and Ellesmere Port, to the south east. -

Sutton Kersh 080421

Registration closes promptly at 12pm on Wednesday 7 April and you must be pre-registered before this time in order to bid property auction Thursday 8 April 2021 12 noon prompt Please note this auction will be streamed live online only suttonkersh.co.uk Merseyside’s leading auction team… James Kersh BSc (Hons) Cathy Holt MNAEA Andrew Binstock MRICS MNAVA BSc (Hons) Director Associate Director Auctioneer james@ cathy.holt suttonkersh.co.uk @suttonkersh.co.uk Katie Donohue Victoria Kenyon MNAVA BSc (Hons) MNAVA Business Development Auction Valuer/Business Manager Development Manager victoria.kenyon@ katie@ suttonkersh.co.uk suttonkersh.co.uk Shannen Woods MNAVA Elle Benson Tayla Dooley Lucy Morgan Paul Holt Auction Administrator Auction Administrator Auction Administrator Auction Administrator Auction Viewer shannen@ elle.benson@ tayla.dooley@ lucy.morgan@ paul.holt@ suttonkersh.co.uk suttonkersh.co.uk suttonkersh.co.uk suttonkersh.co.uk suttonkersh.co.uk Contact 2021 Auction Dates Cathy Holt MNAEA MNAVA Auction Closing [email protected] Thursday 18 February Friday 22 January Thursday 8 April Friday 12 March Katie Donohue BSc (Hons) MNAVA [email protected] Thursday 20 May Friday 23 April Thursday 15 July Friday 18 June BSc Hons MRICS James Kersh Wednesday 8 September Friday 13 August [email protected] Thursday 21 October Friday 24 September for free advice or to arrange a free valuation Thursday 9 December Friday 12 November 0151 207 6315 [email protected] Welcome Welcome to our second auction of 2021 which as usual will start at 12 noon prompt! 132 lots available The sale will be live streamed once again with the ever vibrant auctioneer Andrew Binstock gracing our screens to conduct 60+ 50+ proceedings. -

200 Ton Shop

TO LET • 27,404 SQ FT (2,545.9 SQ M) • HIGHBAY WAREHOUSE • 20 METRES TO EAVES • OVERHEAD CRANEAGE • CLOSE PROXIMITY TO MERSEY TUNNEL AND M53 WALLASEY200 TON SHOP SMM BUSINESS PARK, DOCK ROAD, CH41 1DT ENTER WALLASEY 200 TON SHOP AERIAL LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION SMM BUSINESS PARK, DOCK ROAD, CH41 1DT LIVERPOOL FREEPORT & L2 TERMINAL RIVER MERSEY KINGSWAY TUNNEL ENTRANCE TO M53 WALLASEY 200 TON SHOP A5139 CLICK FOR CLOSE UP AERIAL A554 WALLASEY 200 TON SHOP AERIAL LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION SMM BUSINESS PARK, DOCK ROAD, CH41 1DT A5139 DOCK ROAD A5027 GORSEY LANE WALLASEY 200 TON SHOP KINGSWAY TUNNEL ENTRANCE A59 M53 1.9 MILES (4 MINS) WALLASEY 200 TON SHOP AERIAL LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY FURTHER INFORMATION SMM BUSINESS PARK, DOCK ROAD, CH41 1DT P R O M E A N 5 A 5 D 4 E B R IG H T O A N 55 1 B S OR T OUGH R R E O E E AD N T A L K L ING IL S M W AY 8 T 8 U 0 NN 5 A E A 5 L 02 7 G O R WALLASEY S E Y 200 TON SHOP L A N E D A O R A 5 E 1 3 G 9 D I D R O L NE B C KIN TUN GSWAY D 8 K R 8 R 0 O 5 A WALLASEY D A D A A E 5 200 TON SHOP 0 H 2 N 7 E K ROA K G DOC D 39 R O 51 I A B R A 4 50 S 5 Birkenhead 3 E 5 0 BA Y A North U E L FO A RT N R E O AD B5 14 6 C OR PO RA TI ON RO AD 5 26 Walkden 1 25 7 M6 A580 24 6 A580 M57 23 WALLASEYBootle 4 200 TON SHOP ST HELENS M62 Wallasey 3 102 22 11 10 A5058 21A 1 M62 9 Moreton 5 6 7 2 1 21 A553 Birkenhead A5300 A557 3 LIVERPOOL A562 20 A41 Widnes A56 Speke 9 4 10 Heswall Liverpool A533 River Mersey John Lennon 11 Airport A540 M53 A557 12 5 6 7 M6 8 Ellesmere Port 9 A533 M56 A556 LOCATION 10 14 A548 The unit is located within the Stone Manganese Marine Business Park on Dock Road South in Wallasey and as such benefits from easy access to 11 A49 15 NORTHWICH Flint the M53 and Birkenhead Town Centre together with Liverpool City Centre via the Mersey Tunnels. -

Liverpool RE L Cavern P STREET X

0 1 0 2 y a M . T. PAU Kingsway (Wallasey) 800 L STR F D EET S 48A O R 101 Tunnel services 838 20.26 .27 .47 56 JUVENAL X P C2 D O AIS 103 130 A PLACE L ALL 150 .420 .430 48.52.52 .53 E V 58 O Y R GASC OY T Liverpool N S L S E T M S A TR D E A B D E RE 136 ET A 53 .53 .55.55 R ET C1 220 432.433.N450 T 101 E . A E R T U S W A R T S O T 56 .118.120 E RO ER C3 T B O C1 R A ALL X E ACE 101 S P (some) SE PL City Centre W H NAYLO 122 .150 RO T H R C3 STREET OW SPENCER STREET . R 101 A D 153.155.156.210 B W S 101 T X53 T O N T. E G L T. S N R HMOND O A 221.241 .250.300 GREAT RIC T R L L D R T L E E A R E D S T EV 101 A C G C1 E 311.350.351.420 S R A . A E 48 C1 C2 S O ES 800 C3 T R R E E T O S T A OW T W L R C R E S L A 103 R D S T 430 .432.433.450 N L L A S MO I S H M T N’ 838 B R C S H I S R 136 892 .X2.X6 R Y E EE E B Everton I A T G B A B H VE E U E GI P N 56 21 U D F ET Park T . -

Assessment of Supporting Habitat Liverpool Docks Aug 2015

Assessment of Supporting Habitat (Docks) for Use by Qualifying Features of Natura 2000 Sites in the Liverpool City Region Ornithology Report Report Ref: 4157.005 August 2015 Assessment of Supporting Habitat (Docks) for Use by Qualifying Features of Natura 2000 Sites in the Liverpool City Region Ornithology Report Document Reference: 4157.005 Version 3.0 August 2015 Prepared by: TEP Genesis Centre Birchwood Science Park Warrington WA3 7BH Tel: 01925 844004 Fax: 01925 844002 e-mail: [email protected] for: Merseyside Environmental Advisory Service First floor Merton House Stanley Road Bootle Merseyside L20 3DL Written: Checked: Approved: MW TR TR CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 3.0 SURVEY METHODS .............................................................................................. 11 4.0 SUMMARY SURVEY FINDINGS ............................................................................ 17 5.0 CONCLUSIONS ..................................................................................................... 82 6.0 DISCUSSION OF IMPLICATIONS RELATING TO NATURA 2000 SITES.............. 83 7.0 REFERENCES & FURTHER READING ................................................................. 86 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Examples of Survey Sheets Appendix 2: Vantage Point Survey Coverage Appendix 3: Tabulated Raw Data Appendix 4: -

Road Closure Notice Be Aware. Plan Ahead

ROAD CLOSURE MAP & BE INFORMATION INSIDE ROAD CLOSURES THAT MAY AWARE. IMPACT YOU There is a detailed traffi c management plan to keep the city moving and to maintain access for residents. However, please do plan ahead as delays and road closures are likely in your area. PLAN Diversion routes for your area are available online at runrocknroll.com/liverpool-road-closures Wider scale diversion and access routes are shown on the map overleaf. To travel across the city please use AHEAD. ROAD Queens Drive and move into the city via County Road, Muirhead Ave, West Derby Road, Prescot Road, Edge Lane, Smithdown Road, Allerton Road, and Mather Ave onto Booker Ave, Aigburth Hall Avenue, and Aigburth ROAD CLOSURE NOTICE Road CLOSURE The traffi c management systems will be implemented over a period of time starting from 6am MAY 26, 2019 until 5pm. Roads will be opened as soon as possible Marathon and Half Marathon when the last runner has passed and when it is safe to do so. May 25 2019: 5k race NOTICE SHOPS/BUSINESSES Access to Liverpool One, Albert Dock, Brunswick ROAD CLOSURE INFORMATION The Rock ‘n’ Roll Liverpool Marathon Races will start Business Area, Riverside Drive, and Sefton St., will at 9:00am on Sunday May 26 at Albert Dock. Runners be maintained throughout the day. Please visit will celebrate the city and it’s culture as they run past runrocknroll.com/liverpool-road-closures for a detailed iconic landmarks such as the Three Graces, Football MAY 26, 2019 list of diversions. stadiums, Matthew Street, Penny Lane, and many other Marathon and Half Marathon BUSINESSES are advised to schedule deliveries sights before running along the Waterfront to reach the outside of the road closure times - see location list fi nish line at the Exhibition Centre Liverpool.