Klass, Winseck, Nanni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fidelity Channel Lineup - El-Dorado-Springs, MO

Fidelity Channel Lineup - El-Dorado-Springs, MO HD MUSTVIEW 471...Hallmark Channel HD 514...Lifetime Movie Network HD ------------------------------------------------------ 472...Hallmark Movies and Mysteries HD 517...FOX Business HD 403...NBC KYTV HD 473...Oxygen HD 523...NFL Network HD 404...FOX KRBK Springfield HD 477...Outdoor Channel HD 526...ESPNews HD 408...HSN HD 479...FOX Sports 2 527...ESPNU HD 410...CBS KOLR HD Springfield 484...NewsNation HD 528...NBCSN HD 412...Ion Television HD 488...Olympic Channel HD 529...Golf Channel HD 413...ABC KSPR HD 489...Investigation Discovery HD 538...Ovation 414...PBS KOZK HD 489...WE TV HD 541...Destination America HD 415...CW KYCW HD Springfield 491...FXM 543...GSN HD 416...Ozark's Local KOZL Springfield HD 492...IFC 545...FYI HD 418...The Weather Channel HD 493...Nat Geo Wild 547...Science Channel HD 422...C-SPAN 3 494...HSN2 HD 554...Tennis Channel 495...Hillsong Channel 557...Hallmark Drama HD 497...Hope Channel 560...Aspire MUSTVIEW 498...Sundance HD 561...Crime and Investigation ------------------------------------------------------ 563...NASA TV 3...NBC KYTV Springfield 564...CBS Sports 4...FOX KRBK Springfield MEGAVIEW 565...Big 10 Network 5...QVC ------------------------------------------------------ 567...ACC Network 8...HSN 23...Disney Channel 10...CBS KOLR Springfield 25...Cartoon Network | Adult Swim 11...INSP 26...Freeform MAXVIEW 13...ABC KSPR Springfield 27...Lifetime ------------------------------------------------------ 14...PBS KOZK Springfield 28...USA 104...Disney XD 15...CW -

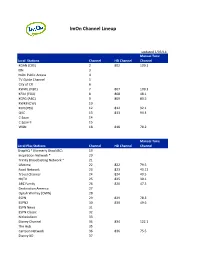

Imon Channel Lineup

ImOn Channel Lineup updated 3/03/14 Manual Tune Local Stations Channel HD Channel Channel KGAN (CBS) 2 802 109.1 ION 3 ImOn Public Access 4 TV Guide Channel 5 City of CR 6 KWWL (NBC) 7 807 109.3 KFXA (FOX) 8 808 48.1 KCRG (ABC) 9 809 83.5 KWKB (CW) 10 KIIN (PBS) 12 812 92.1 QVC 13 813 94.4 C-Span 14 C-Span II 15 WGN 18 818 78.2 Manual Tune Local Plus Stations Channel HD Channel Channel ShopHQ * (formerly ShopNBC) 19 Inspiration Network * 20 Trinity Broadcasting Network * 21 Lifetime 22 822 79.5 Food Network 23 823 40.11 Travel Channel 24 824 40.5 HGTV 25 825 39.1 ABC Family 26 826 47.3 Destination America 27 Oprah Winfrey (OWN) 28 ESPN 29 829 78.3 ESPN2 30 830 49.6 ESPN News 31 ESPN Classic 32 Nickelodeon 33 Disney Channel 34 834 122.1 The Hub 35 Cartoon Network 36 836 75.5 Disney XD 37 Manual Tune Local Plus Stations Channel HD Channel Channel Disney Junior 38 NBC Sports Network 43 843 81.2 Comcast Sportsnet 44 844 88.1 Big Ten Network - moved from ch. 42 45 845 94.5 Bravo 50 850 42.7 TVland 51 Fox Sports 1 52 852 41.21 Oxygen - moved from ch. 45 53 Comedy Central 54 E! Entertainment 55 FX 56 856 83.6 TNT 57 857 81.28 Hallmark 58 Spike 59 AMC 60 TBS 61 861 82.32 USA 62 862 42.8 A&E 63 863 123.3 BET 64 WE tv 69 TCM 70 Syfy 71 871 tru TV 72 872 82.2 Independent Film Channel 73 National Geographic - moved from ch. -

See TV in a Whole

1367 Oxygen HD 1119 Smithsonian Channel 3202 CNN en Espanol 1683 PAC-12 Arizona HD NEW HD (W) NEW 3102 Discovery en Espanol 1684 PAC-12 Bay Area HD NEW 1791 Sony Movie Channel HD NEW 3103 Discovery Familia 1685 PAC-12 Los Angeles HD NEW 1145 Spike TV HD 3051 Disney en Espanol 1686 PAC-12 Mountain HD NEW 1642 Sportsman Channel HD 3052 Disney XD Espanol See TV in a whole 1687 PAC-12 Oregon HD NEW 1337 Sprout HD 3302 ESPN Deportes 1688 PAC-12 Washington HD NEW 1908 Starz! Cinema HD (E) NEW 3077 EWTN en Espanol 1682 PAC-12 Network HD NEW 1904 Starz! Edge HD NEW 3303 FOX Deportes 106 Pay Per View Events HD 1902 Starz! HD (E) NEW 3304 GolTV 1101 Pay Per View Events HD 1903 Starz! HD (W) NEW 3104 History en Espanol 1170 Pets.TV HD NEW 1906 Starz! In Black HD NEW 3056 La Familia Cosmovision 1787 PixL HD NEW 1912 Starz! Kids and Family 3017 Latele Novela 9161 Premier League Extra HD NEW 3078 TBN Enlace Time 1 HD 1931 Starz! On Demand 3024 TV Chile 9162 Premier League Extra 1151 Syfy HD 3020 Video Rola Time 2 HD 1560 TBN HD 3013 WAPA America 9163 Premier League Extra 1112 TBS HD Time 3 HD 1022 The CW HD (WLFLDT) 9164 Premier League Extra 1335 The Hub HD International Channels Time 4 HD 1225 The Weather Channel HD 9165 Premier League Extra 1838 ThrillerMAX HD (E) 3740 Al Jazeera America Time 5 HD 1839 ThrillerMAX HD (W) 3710 Bollywood Hits on Demand 1420 QVC HD 1250 TLC HD 3882 Channel One Russia 1458 Recipe.TV HD NEW 1882 TMC HD (E) NEW 3603 China Central TV 1799 REELZ HD 1883 TMC HD (W) NEW 3604 CTI-Zhong Tian Channel 1916 RetroPlex HD NEW 1888 TMC On Demand 3682 Filipino on Demand Raleigh 1476 RFD-TV HD NEW 1884 TMC Xtra HD (E) NEW 3802 Rai Italia 1258 Science HD 1885 TMC Xtra HD (W) NEW 3704 Sony Entertainment 1424 ShopHQ HD 1108 TNT HD Television Asia (SET Asia) Channel Lineup 1789 ShortsHD NEW 1254 Travel Channel HD 3706 STAR India PLUS 3681 The Filipino Channel Channel lineup is subject to change. -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer. All rights reserved. This log may First issued in August 2001, The PAL lists all known medium wave not reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part in any form, except with broadcasting stations in southern and eastern Asia and the Pacific. It the expressed permission of the author. Contents may be used freely in covers an area extending as far west as Afghanistan and as far east as non-commercial publications and for personal use. Some of the material in Alaska, or roughly one half of the earth's surface! It now lists over 4000 this log was obtained from copyrighted sources and may require special stations in 60 countries, with frequencies, call signs, locations, power, clearance for anything other than personal use. networks, schedules, languages, formats, networks and other information. The log also includes longwave broadcasters, as well as medium wave beacons and weather stations in the region. Acknowledgements Since early 2005, there have been two versions of the Log: a downloadable pdf version and an interactive on-line version. My sources of information include DX publications, DX Clubs, E-bulletins, e- mail groups, web sites, and reports from individuals. Major online sources The pdf version is updated a few a year and is available at no cost. There include Arctic Radio Club, Australian Radio DX Club (ARDXC), British DX are two listings in the log, one sorted by frequency and the other by country. Club (BDXC), various Facebook pages, Global Tuners and KiwiSDR receivers, Hard Core DXing (HCDX), International Radio Club of America The on-line version is updated more often and allows the user to search by (IRCA), Medium Wave Circle (MWC), mediumwave.info (Ydun Ritz), New frequency, country, location, or station. -

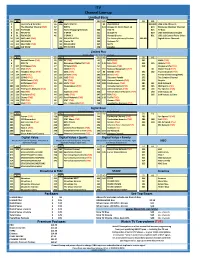

FLIP RIGHT to YOUR TV FAVORITES a Complete Channel Guide

Channel Lineup Destin/Niceville Destin/Niceville January 2016 FLIP RIGHT TO YOUR TV FAVORITES A complete channel guide. For the most recent Channel Line Up, please visit www.cox.com/channels TV Starter 2 ABC - WMBB (Panama City) 10 FOX - WALA (Mobile) 19 HSN 81 C-SPAN 2 Δ 119 The Country Network - WEAR Δ 3 ABC - WEAR (Pensacola) 11 TBS 20 QVC 82 C-SPAN 3 Δ 692 This TV - WMBB (Panama City) Δ 4 CBS - WECP (Panama City ) 12 My Network - WFGX (Pensacola) 22 IND - WFBD (Destin) Δ 84 POP TV Δ 693 PBS World - WSRE DT (Pensacola) Δ 5 CBS - WKGR (Mobile) 13 CTN - WHBR 23 IND - WAWD (Fort Walton) 88 Jewelry TV Δ 694 PBS Plus - WSRE DT (Pensacola) Δ 6 Cox 6 14 TBN - WMPV (Mobile) 24 WGN America 112 Comet TV - WFGX Δ 695 PBS VeMe - WSRE DT (Pensacola) Δ 7 NBC - WJHG (Panama City) 15 CW - WFNA (Mobile) 39 Leased Access Δ 115 Grit TV - WJTC DT2 (Mobile) Δ 696 Weather Nation - WPMI DT Δ 8 NBC - WPMI (Mobile) 16 IND - WJTC (Mobile) 67 TVGN (Scrolling) Δ 116 GetTV - WFGX (Pensacola) Δ 699 Me TV - WKRG Δ 9 PBS - WSRE (Pensacola) 17 Daystar - WDPM (Mobile) 80 C-SPAN Δ 117 Bounce TV - WFNA DT (Mobile) Δ TV Starter HD 1002 ABC HD - WMBB (Panama City) 1007 NBC HD - WJHG 1011 TBS HD 1016 UPN HD - WJTC 1023 IND HD -WAWD (Fort Walton Beach) 1003 ABC HD - WEAR (Pensacola) 1008 NBC HD - WPMI (Mobile) 1012 My Network HD - WFGX (Pensacola) 1019 HSN HD 1024 WGN America HD 1004 CBS HD - WECP ( Panama City)) 1009 PBS HD - WSRE (Pensacola) 1013 CTN HD - WHBR 1020 QVC HD 1084 Pop TV 1005 CBS HD - WKRG (Mobile) 1010 FOX HD - WALA (Mobile) 1015 CW HD - WFNA (Mobile) 1022 -

Itv Channel Line-Up

iTV Channel Line-up Limited Basic SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 2 Local Info & Weather 36 136 MyTV KMTW 94 PBS KOODW 800-809 H&B Help Channels 3 The Weather Channel (TVE) 37 EWTN 113 Always On Storm Team 12 813 Ellinwood Chamber Channel 4 104 FOX KSAS 39 Home Shopping Network 220 TBD TV 815 TV Boss 8 81 PBS KPTS 40 C-SPAN 221 Charge TV 820 USD 355 Ellinwood Eagles 9 91 PBS KOOD 41 C-SPAN 2 222 Heroes & Icons 821 USD 112 Central Plains Oilers 10 110 ABC KAKE (TVE) 82 PBS KIDS KPTS1 233 The Country Network/Stadium 900-929 Digital Music Channels 12 112 CBS KWCH 83 Create TV 235 Antenna TV 22 102 NBC KSNC (TVE) 92 PBS KOODH 237 MeTV 33 133 CW KSCW 93 PBS KOOD3 238 Decades Limited Plus (Includes all channels in Limited Basic Package) SD HD SD HD SD HD SD HD 5 Animal Planet (TVE) 25 125 FX (TVE) 48 MTV (TVE) 251 OWN (TVE) 6 RFD-TV 26 Paramount (Spike TV) (TVE) 49 149 SyFy (TVE) 255 155 History (TVE) 7 107 FOX News (TVE) 27 TV Land (TVE) 50 Discovery (TVE) 258 Discovery Life (TVE) 11 111 CNN (TVE) 28 WGN (TVE) 51 151 National Geographic (TVE) 161 Motor Trend (TVE) 13 95 Headline News (TVE) 29 AMC (TVE) 52 96 MSNBC (TVE) 262 162 Travel Channel (TVE) 14 114 ESPN (TVE) 30 130 Lifetime (TVE) 202 199 Bravo (TVE) 271 Trinity Broadcasting (TBN) 15 115 ESPN2 (TVE) 31 131 A&E (TVE) 203 Discovery Family 272 The Cowboy Channel 16 ESPN Classic (TVE) 34 TLC (TVE) 207 198 Cartoon Network (TVE) 273 Daystar 17 ESPN News (TVE) 35 135 HGTV (TVE) 212 108 Fox Business (TVE) 281 181 MLB Network 282 116 ESPN U (TVE) 38 Nickelodeon (TVE) 236 Comedy Central (TVE) 285 185 -

Channel Lineup

channel lineup 34 ¯ History Channel ¯ BASIC SERVICE 35 ¯ Discovery Channel ¯ DIGITAL CHANNELS 36 ¯ Animal Planet ¯ DIGITAL PREMIUMS 37 ¯ Travel Channel ¯ DIGITAL MUSIC 38 ¯ National Geographic Channel n HIGH DEFINITION TELEVISION 39 ¯ TLC 40 ¯ Disney Channel 2 ¯ CW 41 ¯ Disney XD 3 ¯ WHOI-ABC 19 Peoria 42 ¯ ABC Family 4 ¯ WEEK-NBC 25 Peoria 43 ¯ Cartoon Network 5 ¯ WMBD-CBS 31 Peoria 44 ¯ Nickelodeon 6 ¯ WTVP-PBS 47 Peoria 45 ¯ TV Land 7 ¯ TBS Superstation 46 ¯ Hallmark Channel 8 ¯ WYZZ FOX 43 Bloomington 47 ¯ Disney Jr 9 ¯ WGN 9 Chicago 48 ¯ CMT 10 ¯ WAOE UPN 59 Peoria/Blm 49 ¯ Great American Country 11 ¯ The Weather Channel 50 ¯ VH1 12 ¯ Community Channel 51 ¯ MTV 13 ¯ CNN 53 ¯ American Movie Classics 14 ¯ Home Shopping Network 54 ¯ Turner Classic Movies 15 ¯ MSNBC 55 ¯ Bravo 16 ¯ Fox News Channel 56 ¯ Lifetime Television 17 ¯ FoxPROOF Business News 57 ¯ USA Network 18 ¯ CNBC 58 ¯ Spike TV 19 ¯ C-SPAN 59 ¯ Comedy Central 20 ¯ Fox Sports 1 60 ¯ FX 21 ¯ NBC Sports Network 61 ¯ TNT 22 ¯ ESPNU 62 ¯ SyFy 23 ¯ Big Ten Alternate 63 ¯ FXX 24 ¯ Comcast SportsNet Chicago 307 ¯ Turner Classic Movies 25 ¯ Big Ten Network 308 ¯ GSN 26 ¯ NFL Network 311 ¯ Esquire 27 ¯ Fox Sports Midwest 315 ¯ YouToo 28 ¯ ESPN 320 ¯ National Geographic Channel 29 ¯ ESPN 2 326 ¯ OWN Oprah Winfrey Network 30 ¯ ESPN Classic 328 ¯ Destination America 31 ¯ Home and Garden 329 ¯ HUB 32 ¯ Food Network 330 ¯ American Heroes Channel 33 ¯ A & E 331 ¯ Investigation Discovery 747.2324 more channel lineup 332 ¯ Science Channel 107 n PBS Create HD 335 ¯ SyFy 108 n Fox HD 340 ¯ Biography -

ENTERTAINMENT PACKAGES/CHANNEL GUIDE Toll Free: 1.877.814.7101 BASIC PREMIUM DIGITAL

210401 Turn on the TV and let the music take off! Enjoy 50 commercial-free audio channels! Included with all cable packages. 905 ADULT ALTERNATIVE 930 NOTHING BUT 90’S 906 CLASSIC MASTERS 931 MAXIMUM PARTY 907 CLASSIC ROCK 932 DANCIN CLUBBIN’ 908 COUNTRY CLASSICS 935 BLUEGRASS 909 EASY LISTENING 937 HIP HOP 910 FLASHBACK 70’S 939 JAZZ NOW 911 FOLK ROOTS 941 THE CHILL LOUNGE 912 HIT LIST 942 THE SPA 913 HOT COUNTRY 943 BROADWAY 914 JAMMIN’ 944 ECLECTIC ELECTRONIC 915 JAZZ MASTERS 945 CHAMBER MUSIC 916 JUKEBOX OLDIES 946 ÉXITOS DEL MOMENTO 917 KID STUFF 947 CLASSIC R&B SOUL 918 ÉXITOS TROPICALES 948 NO FENCES 919 POP ADULT 949 GROOVE DISCO & FUNK 920 POP CLASSIC 950 HOLIDAY HITS 921 EVERYTHING 80’S 951 HEAVY METAL 922 ROCK 952 ALT COUNTRY AMERICANA 923 ALTERNATIVE 953 ALT ROCK CLASSICS 924 SMOOTH JAZZ 954 GOSPEL 925 SOUL STORM 955 GALAXIE Y2K 926 SWINGING STANDARDS 956 RETRO LATINO 927 THE BLUES 957 RITMOS LATINOS 928 CHRISTIAN POP & ROCK 958 ROCK EN ESPANOL 929 HIP-HOP/R&B 959 ROMANCE LATINO ENTERTAINMENT PACKAGES/CHANNEL GUIDE www.prtcnet.org Toll Free: 1.877.814.7101 BASIC PREMIUM DIGITAL $41.00 MOVIE CHANNELS Discounts available when you add multiple Premium Movie Channel packages. +taxes/fees 1 IPTV TUTORIAL 129 THIS TV 100 WLEX (NBC) 130 START TV 101 ME TV 131 CHARGE! *Must have Basic 102 WTVQ (ABC) 132 TBD *Must have Basic 103 MY KY 133 KET + $17.95 + $11.95 104 JUSTICE NETWORK 134 COURT TV MYSTERY 105 WKYT (CBS) 135 COURT TV 601 HBO 621 STARZ 106 WKYT2 (CW) 136 CIRCLE 602 HBO FAMILY 622 STARZ CINEMA 107 WEATHER RADAR 137 AMG TV -

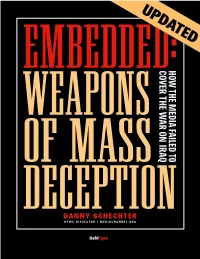

Weapons of Mass Deception

UPDATED. EMBEDDEDCOVER THE WAR ON IRAQ HOW THE TO MEDIA FAILED . WEAPONS OF MASS DECEPTIONDANNY SCHECHTER NEWS DISSECTOR / MEDIACHANNEL.ORG ColdType WHAT THE CRITICS SAID This is the best book to date about how the media covered the second Gulf War or maybe miscovered the second war. Mr. Schecchter on a day to day basis analysed media coverage. He found the most arresting, interesting , controversial, stupid reports and has got them all in this book for an excellent assessment of the media performance of this war. He is very negative about the media coverage and you read this book and you see why he is so negative about it. I recommend it." – Peter Arnett “In this compelling inquiry, Danny Schechter vividly captures two wars: the one observed by embedded journalists and some who chose not to follow that path, and the “carefully planned, tightly controlled and brilliantly executed media war that was fought alongside it,” a war that was scarcely covered or explained, he rightly reminds us. That crucial failure is addressed with great skill and insight in this careful and comprehensive study, which teaches lessons we ignore at our peril.” – Noam Chomsky. “Once again, Danny Schechter, has the goods on the Powers The Be. This time, he’s caught America’s press puppies in delecto, “embed” with the Pentagon. Schechter tells the tawdry tale of the affair between officialdom and the news boys – who, instead of covering the war, covered it up. How was it that in the reporting on the ‘liberation’ of the people of Iraq, we saw the liberatees only from the gunhole of a moving Abrams tank? Schechter explains this later, lubricious twist, in the creation of the frightening new Military-Entertainment Complex.” – Greg Palast, BBC reporter and author, “The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.” "I'm your biggest fan in Iraq. -

Fidelitytv Channel Lineup - Adrian, MO

FidelityTV Channel Lineup - Adrian, MO MUSTVIEW 79...The Country Network 221...Cinemax ------------------------------------------------------ 80...Revolt 223...More Max 3...PBS 81...Jewelry TV 225...Action Max 4...FOX 87...INSP 227...ThrillerMax 5...CBS 88...Olympic Channel 230...Max Spanish 6...Court TV Mystery 90...BBC America 232...OuterMax 8...MyNetworkTV 91...FXM 234...5starMax 9...ABC 92...IFC 10...QVC 93...Nat Geo Wild 11...Ion Television 95...Hillsong Channel SHOWTIME & THE MOVIE CHANNEL 12...NBC 96...SonLife ------------------------------------------------------ 14...HSN2 97...Hope Channel 241...Showtime 15...TBN 98...Sundance 243...Showtime 2 16...HSN 99...PosiTV 245...Showtime Showcase 17...CW 100...Motor Trend 247...Showtime Extreme 18...Comet 250...Showtime Next 19...PBS 252...Showtime Family 20...The Weather Channel MAXVIEW 254...Showtime Women 21...EWTN ------------------------------------------------------ 256...FLIX 22...C-SPAN 101...Kids Central 258...SHO*BET 23...C-SPAN 2 102...Universal Kids 261...The Movie Channel 31...C-SPAN 3 105...Disney XD 263...The Movie Channel Xtra 171...MeTV 106...Disney Junior 172...Antenna TV 107...Discovery Family 175...Bounce TV 114...American Heroes Channel STARZ & ENCORE 187...TrueCrime 116...Turner Classic Movies ------------------------------------------------------ 117...QVC2 271...STARZ 119...POP 274...STARZ Edge MEGAVIEW 120...DIY 276...STARZ Cinema ------------------------------------------------------ 122...WE TV 278...STARZ Kids & Family 24...Disney Channel 123...Cooking Channel -

Chicago 2020 Channel Lineup

Hispanic MiVisión Lite 800 History en Español 824 Music Choice Pop Tropicales 780 FXX 801 WGBO Univision 825 Discovery Familia 784 De Pelicula Clasico 802 WSNS Telemundo 826 Sorpresa 785 De Pelicula 803 WXFT UniMas 827 Ultra Familia 786 Cine Mexicano 804 Galavision 828 Disney XD (SAP) 787 Cine Latino 806 Fox Deportes 829 Boomerang (SAP) 788 Tr3s 809 TBN Enlace 830 Semillitas 789 Bandamax 810 EWTN en Español 831 Tele El Salvador 790 Telehit 811 Mundo FOX 832 TV Dominicana 791 Ritmoson 813 CentroAmerica TV 833 Pasiones 792 Tele Novela 814 WCHU 793 FOX Life 815 WAPA America MiVisión Plus 794 NBC Univsero 816 Telemicro Internacional Includes ALL MiVisión Lite channels PLUS 795 Discovery en Español 817 Caracol TV 369 (805 HD) ESPN Deportes 796 TVN Chile 818 Ecuavisa Internacional 808 beIN Sport 797 TV Española 821 Music Choice Pop Latino 820 Gran Cine 798 CNN en Español 822 Music Choice Mexicana 834 Viendo Movies 799 Nat Geo Mundo 823 Music Choice Urbana RCN On Demand With RCN On Demand get unlimited access to thousands of hours of popular content whenever you want - included FREE* with your Streaming TV subscription! We’ve added 5x the capacity to RCN On Demand, so you never have to miss a moment. Get thousands of hours of programming including more of your favorites from Fox, NBC, A&E, Disney Jr. and more with over 40 new networks. The best part is it’s all included with your RCN Streaming TV!* It’s easy as 1-2-3: 1. Press the VOD or On Demand button on your RCN remote.