Economic Activity in Quernmore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Blood Service-Lancaster

From From Kendal Penrith 006) Slyne M6 A5105 Halton A6 Morecambe B5273 A683 Bare Bare Lane St Royal Lancaster Infirmary Morecambe St J34 Ashton Rd, Lancaster LA1 4RP Torrisholme Tel: 0152 489 6250 Morecambe West End A589 Fax: 0152 489 1196 Bay A589 Skerton A683 A1 Sandylands B5273 A1(M) Lancaster A65 A59 York Castle St M6 A56 Lancaster Blackpool Blackburn Leeds M62 Preston PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - BARTHOLOMEW(2 M65 Heysham M62 A683 See Inset A1 M61 M180 Heaton M6 Manchester M1 Aldcliffe Liverpool Heysham M60 Port Sheffield A588 e From the M6 Southbound n N Exit the motorway at junction 34 (signed Lancaster, u L Kirkby Lonsdale, Morecambe, Heysham and the A683). r Stodday A6 From the slip road follow all signs to Lancaster. l e Inset t K A6 a t v S in n i Keep in the left hand lane of the one way system. S a g n C R e S m r At third set of traffic lights follow road round to the e t a te u h n s Q r a left. u c h n T La After the car park on the right, the one way system t S bends to the left. A6 t n e Continue over the Lancaster Canal, then turn right at g e Ellel R the roundabout into the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (see d R fe inset). if S cl o d u l t M6 A h B5290 R From the M6 Northbound d Royal d Conder R Exit the motorway at junction 33 (signed Lancaster). -

ALDCLIFFE with STODDAY PARISH COUNCIL

ALDCLIFFE with STODDAY PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting held on 1st June 2021 at 7.00pm at the Quaker Meeting House, Lancaster Present: Councillor Nick Webster (Chairman) Councillors Denise Parrett and Duncan Hall. City Councillor Tim Dant Derek Whiteway, Parish Clerk One member of the public attended the meeting 21/032 Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Councillors Kevan Walton and Chris Norman and from County Councillor Gina Dowding. 21/033 Minutes of the previous meeting 1) The minutes of the Parish Council Annual Meeting held on 4th May 2021, were approved subject to a minor typographical change to minute 21/016(b) – appointment of the Deputy Chair for 2021/22. Matters arising: 2) 21/029(3) – Lengthsman. The Chairman reported that the Lengthsman had cleared the steps leading from leading from the Smuggler’s Lane public footpath onto the estuary multi-use path. The Lengthsman had advised that handrails were not generally installed in such locations, but that alternative options to assist walkers when negotiating the steps would be considered. 21/034 Declarations of Interest No further declarations were made. 21/035 Planning Applications No new planning applications had been referred to the Parish Council since the last meeting. 21/036 Councillors’ Roles The Clerk reported that a request had been received from Scotforth Parish Council inviting Councillors, along with those from Thurnham with Glasson and Ellel Parish Councils, to collaborate in a meeting to discuss issues presented by Bailrigg Garden Village (BGV) developments. Councillors agreed that this would be beneficial and resolved to respond positively to the invitation. -

Quernmore Link

HAPPY EASTER! Quernmore Link Village Churches School Sports dqowbenefice.co.uk ST. PETERS CHURCH MAGAZINE SERVICES AT ST. PETER’S Sunday 24th March – 3rd Sunday of Lent 9.30am Eucharist Sunday 31st March - Mothering Sunday 9.30am Mothering Sunday service Sunday 7th April - Passiontide Begins 10am Family Service Sunday 14th April - Palm Sunday 9.30am Palm Sunday Eucharist Sunday 21st April - Easter Day 9.30am Easter Eucharist Sunday 28th April - 2nd Sunday of Easter 9.30am Eucharist Sunday 5th May - 3rd Sunday of Easter 10am Family Service Sunday 12th May—4th Sunday of Easter 9.30am Eucharist Sunday 19th May—5th Sunday of Easter 9.30am Morning Prayer For more information about St Peter’s please log on to dqowbenefice.co.uk The website contains a calendar of services and events and you can access the weekly pew sheet even if you miss the service! Next edition of Quernmore2 Link—June 2019 From the Editor I hope that you enjoy the Spring 2019 edition of the Quernmore Link. Please feel free to share it with friends and neighbours. The Link is also available in glorious colour on the Church website . If you haven’t discovered it yet you can find the website at Dqowbenefice.co.uk You will find lots of up-to-date information on the website about church services and events . Make sure you look at the ‘Blog’ section to access the weekly Pew Sheet. You can subscribe to the Pew Sheet with a single click! The schedule of publication for the Link for 2019 is Summer/Pentecost edition - early June Autumn/Harvest edition - early September Winter/Advent edition - mid November Particular thanks for contributions in this edition to Stephen and Audrey Potter Margaret Standen David Curwen Cindy The cover displays the banner ‘Village Churches School Sports’ and all contributions, written pieces, photographs, reviews, adverts, notices, will be gratefully received and there will always be space……. -

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

APPLY ONLINE the Closing Date for Applications Is Wednesday 15 January 2020

North · Lancaster and Morecambe · Wyre · Fylde Primary School Admissions in North Lancashire 2020 /21 This information should be read along with the main booklet “Primary School Admissions in Lancashire - Information for Parents 2020-21” APPLY ONLINE www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools The closing date for applications is Wednesday 15 January 2020 www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools This supplement provides details of Community, Voluntary Controlled, Voluntary Aided, Foundation and Academy Primary Schools in the Lancaster, Wyre and Fylde areas. The policy for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools is listed on page 2. For Voluntary Aided, Foundation Schools and Academies a summary of the admission policy is provided in this booklet under the entry for each school. Some schools may operate different admission arrangements and you are advised to contact individual schools direct for clarification and to obtain full details of their admission policies. These criteria will only be applied if the number of applicants exceeds the published admission number. A full version of the admission policy is available from the school and you should ensure you read the full policy before expressing a preference for the school. Similarly, you are advised to contact Primary Schools direct if you require details of their admissions policies. Admission numbers in The Fylde and North Lancaster districts may be subject to variation. Where the school has a nursery class, the number of nursery pupils is in addition to the number on roll. POLICIES ARE ACCURATE AT THE TIME OF PRINTING AND MAY BE SUBJECT TO CHANGE Definitions for Voluntary Aided and Foundation Schools and Academies for Admission Purposes The following terms used throughout this booklet are defined as follows, except where individual arrangements spell out a different definition. -

477 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

477 bus time schedule & line map 477 Lancaster Caton Road - Kirkby Lonsdale Qes View In Website Mode The 477 bus line (Lancaster Caton Road - Kirkby Lonsdale Qes) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kirkby Lonsdale: 7:25 AM (2) Lancaster City Centre: 3:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 477 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 477 bus arriving. Direction: Kirkby Lonsdale 477 bus Time Schedule 43 stops Kirkby Lonsdale Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:25 AM Chapel Street, Lancaster City Centre 2 Chapel Street, Lancaster Tuesday 7:25 AM Sainsbury's Layby, Lancaster City Centre Wednesday 7:25 AM A6, Lancaster Thursday 7:25 AM Our Ladys Rchs, Skerton Friday 7:25 AM Aldrens Lane, Skerton Saturday Not Operational Aldrens Lane, Lancaster Daisy Street, Skerton Daisy Street, Lancaster 477 bus Info Hill Road, Skerton Direction: Kirkby Lonsdale Hill Road, Lancaster Stops: 43 Trip Duration: 65 min The Green, Beaumont Line Summary: Chapel Street, Lancaster City Centre, Wilton Close, Lancaster Sainsbury's Layby, Lancaster City Centre, Our Ladys Rchs, Skerton, Aldrens Lane, Skerton, Daisy Street, Woodlands Road, Beaumont Skerton, Hill Road, Skerton, The Green, Beaumont, Pollard Place, England Woodlands Road, Beaumont, Kellet Lane, Beaumont, Halton Camp, Halton, Bay Gateway, Halton, War Kellet Lane, Beaumont Memorial, Halton, Community Centre, Halton, Forgewood Drive, Halton, Lune Bridge, Caton, Halton Camp, Halton Quernmore Road, Caton, Station Hotel, Caton, Beckside, -

Fylde Local Plan COPIES of REPRESENTATIONS MADE TO

Fylde Local Plan COPIES OF REPRESENTATIONS MADE TO THE MAIN MODIFICATIONS CONSULTATION April 2018 2 3 List of representors Ref Representor Main Modifications Page 2 BAE Systems – Cass Associates MM17, MM58, MM59. 7 4 Blackpool Council MM37, MM60, MM61. 8 5 Britmax Developments - Indigo MM31. 12 Planning 6 Canal & River Trust General comment only 14 7 CAPOW MM67. 15 10 Chris Hill - De Pol Associates MM17. 20 13 Environment Agency MM13. 25 15 Friends of the Earth General comment only 26 16 Gladman Developments MM1, MM6, MM29, MM40, 27 MM73 18 Greenhurst Investments - Indigo MM31, MM32, MM36, 30 Planning MM40, MM73. 20 Highways England General comment only 35 21 Historic England General comment only 36 22 Hollins Strategic Land MM1, MM6, MM13, MM40, 38 MM41, MM42, MM67. 23 Home Builders Federation MM6, MM29, MM30, MM40, 45 MM42, MM43, MM73. 26 John Coxon - Smith & Love MM15. 47 31 Lancashire County Council MM51, MM52. 51 34 Mactaggart & Mickel - Colliers MM41, MM72 54 International 36 Metacre Ltd - De Pol Associates MM1, MM6, MM21, MM23, 57 MM29, MM31, MM40, MM42, MM48, MM73. 4 Ref Representor Main Modifications Page 47 Natural England General comment only 62 50 Nuclear Decommissioning Comment on failure to modify 63 Authority - GVA policy EC1. 51 Oyston Estates - Cassidy & MM1, MM6, MM40. 65 Ashton 52 Persimmon Homes MM6, MM29, MM30, MM40, 67 MM42, MM43. 59 Strategic Land Group - Turley MM1, MM6, MM40, MM41. 69 60 Taylor Wimpey - Lichfields MM6, MM14, MM17, MM40. 170 64 Trams to Lytham MM62. 180 65 Treales Roseacre & Wharles MM2, MM50, MM69. 181 Parish Council 66 United Utilities MM25. -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 7 Territorial Boundaries This may seem a superfluous title for an eponymous society, so a few words of explanation are thought necessary. The Society’s sometime reluctance to expand its interests beyond the city boundary has not prevented a more elastic approach when the situation demands it. Indeed it is not true that the Society has never been prepared to look beyond the City boundary. As early as 1971 the committee expressed a wish that the Society might be a pivotal player in the formation of amenity bodies in the surrounding districts. It was resolved to ask Sir Frank Pearson to address the Society on the issue, although there is no record that he did so. When the Society was formed, and, even before that for its predecessor, there would have been no reason to doubt that the then City boundary would also be the Society’s boundary. It was to be an urban society with urban values about an urban environment. However, such an obvious logic cannot entirely define the part of the city which over the years has dominated the Society’s attentions. This, in simple terms might be described as the city’s historic centre – comprising largely the present Conservation Areas. But the boundaries of this area must be more fluid than a simple local government boundary or the Civic Amenities Act. We may perhaps start to come to terms with definitions by mentioning some buildings of great importance to Lancaster both visually and strategically which have largely escaped the Society’s attentions. -

Access Statement for Williamson Park, Lancaster

Access Statement for Williamson Park, Lancaster Williamson Park is situated on the outskirts of the City of Lancaster. It is home to the iconic Ashton Memorial and 54 acres of beautiful parkland with enchanting woodland walks, play areas and breath taking views to the Fylde Coast, Morecambe Bay and the Lake District. The park features a cafe and gift-shop, Butterfly House (formerly a tropical palm house), and is resident to a host of mini beasts, reptiles, birds and meerkats. The park and all amenities are open all year except Christmas Day, Boxing Day and New Year's Day. Our opening times are: October to March: 10am to 4pm April to September: 10am to 5pm The entry to Williamson Park grounds are free with entry to the Butterfly House, mini beasts and small animal zoo available for purchase at the gift shop. There are two pay and display car parks in Williamson Park - at the Quernmore Road entrance (15 spaces, including disabled parking) and at the Wyresdale Road entrance (100 spaces). Quernmore Road Entrance which leads to parking including disabled parking, The Pavillion Café, Butterfly House and Ashton Memorial. Arrival and Car Parking Facilities We have two Pay and Display car parks at Williamson Park; Quernmore Road and Wyresdale Road. We would encourage those with mobility problems to use the Quernmore Road entrance which leads to the car park closer to the park’s facilities. There is no signed disabled parking but ample space for several cars. Our car park at Wyresdale road offers more parking spaces, however there is quite a walk uphill to reach the facilities. -

Initial Template Document

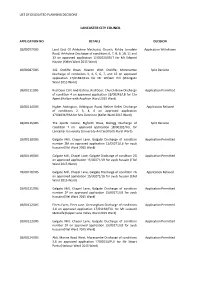

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 18/00077/DIS Land East Of Arkholme Methodist Church, Kirkby Lonsdale Application Withdrawn Road, Arkholme Discharge of conditions 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 13 on approved application 15/01024/OUT for Mr Edward Hayton (Kellet Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00087/DIS 342 Oxcliffe Road, Heaton With Oxcliffe, Morecambe Split Decision Discharge of conditions 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 15 on approved application 17/01384/FUL for Mr William Hill (Westgate Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00111/DIS Red Door Cafe And Gallery, Red Door, Church Brow Discharge Application Permitted of condition 4 on approved application 18/00241/LB for C/o Agent (Halton-with-Aughton Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00114/DIS Higher Addington, Addington Road, Nether Kellet Discharge Application Refused of conditions 2, 3, 4, 6 on approved application 17/01034/PAA for Mrs Dennison (Kellet Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00115/DIS The Sports Centre, Bigforth Drive, Bailrigg Discharge of Split Decision condition 7 on approved application 18/00102/FUL for Lancaster University (University And Scotforth Rural Ward) 18/00118/DIS Galgate Mill, Chapel Lane, Galgate Discharge of condition Application Permitted number 2M on approved application 15/00271/LB for ayub hussain (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00119/DIS Galgate Mill, Chapel Lane, Galgate Discharge of condition 2G Application Permitted on approved application 15/00271/LB for ayub hussain (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00120/DIS Galgate Mill, Chapel Lane, Galgate Discharge of condition 2A Application