Legaisavoir.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Juliet Berto (1947-1990)

Communiqué de presse Merci de bien vouloir diffuser cette info Emmanuelle De Schrevel 02 551 19 40 [email protected] A CINEMATEK (Rue Baron Horta 9, 1000 Bruxelles) du 02.12 au 24.01 un programme Juliet Berto (1947-1990) Introduction Programmer Juliet Berto au-delà des célébrations d’anniversaire de Mai 1968 dont elle est une icône, c’est choisir de rendre hommage à une femme sensible et drôle, à une manière de vivre « autre », qui s’exprime à travers l’actrice impulsive au corps fragile, devenue réalisatrice avec l’urgence de retrouver la magie première du cinéma, pour témoigner de l’optimisme présent chez ceux qui recherchent désespérément l’essentiel et un équilibre, face au vent. C’est découvrir d’autres films dans lesquels elle a joué, ainsi que les trois longs métrages qu’elle a réalisés. Ils n’ont pour la majorité jamais été montrés dans nos salles. Juliet Berto Lors d’un ciné-club à Grenoble elle fait la rencontre de Godard et part pour Paris. Celui-ci l’immortalise dans ses films en icône de la génération 1968. À travers le cinéma commercial, elle se forge ensuite au métier de comédienne. En Alain Tanner, pour qui elle joue dans deux films, elle trouve quelqu’un comme elle en périphérie de la nouvelle vague, aux larges horizons. Attirée par le tiers-monde elle découvre chez Glauber Rocha un cinéma en écho à son désir de vie, de rythme... Au milieu des années 1970, l’actrice autodidacte redécouvre chez Jacques Rivette le plaisir de jouer « comme quand on est enfant », tout en coécrivant Céline et Ju lie vont en bateau. -

GODARD FILM AS THEORY Volker Pantenburg Farocki/Godard

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FAROCKI/ GODARD FILM AS THEORY volker pantenburg Farocki/Godard Farocki/Godard Film as Theory Volker Pantenburg Amsterdam University Press The translation of this book is made possible by a grant from Volkswagen Foundation. Originally published as: Volker Pantenburg, Film als Theorie. Bildforschung bei Harun Farocki und Jean-Luc Godard, transcript Verlag, 2006 [isbn 3-899420440-9] Translated by Michael Turnbull This publication was supported by the Internationales Kolleg für Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie of the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar with funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. IKKM BOOKS Volume 25 An overview of the whole series can be found at www.ikkm-weimar.de/schriften Cover illustration (front): Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, Chapter 4B (1988-1998) Cover illustration (back): Interface © Harun Farocki 1995 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 891 4 e-isbn 978 90 4852 755 7 doi 10.5117/9789089648914 nur 670 © V. Pantenburg / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. -

GODARD and the CINEMATIC ESSAY by Charles Richard Warner

RESEARCH IN THE FORM OF A SPECTACLE: GODARD AND THE CINEMATIC ESSAY by Charles Richard Warner, Jr. B.A., Georgetown College, 2000 M.A., Emory University, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Charles Richard Warner, Jr. It was defended on September 28, 2010 and approved by Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Randalle Halle, Klaus Jones Professor, Department of German Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Colin MacCabe, Distinguished University Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Assistant Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Associate Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Rick Warner 2011 iii RESEARCH IN THE FORM OF A SPECTACLE: GODARD AND THE CINEMATIC ESSAY Charles Richard Warner, Jr., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation is a study of the aesthetic, political, and ethical dimensions of the essay form as it passes into cinema – particularly the modern cinema in the aftermath of the Second World War – from literary and philosophic sources. Taking Jean-Luc Godard as my main case, but encompassing other important figures as well (including Agnès Varda, Chris Marker, and Guy Debord), I show how the cinematic essay is uniquely equipped to conduct an open-ended investigation into the powers and limits of film and other audio- visual manners of expression. I provide an analysis of the cinematic essay that illuminates its working principles in two crucial respects. -

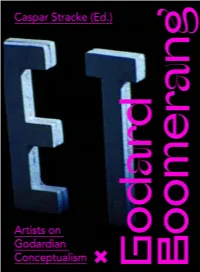

Caspar Stracke (Ed.)

Caspar Stracke (Ed.) GODARD BOOMERANG Godardian Conceptialism and the Moving Image Francois Bucher Chto Delat Lee Ellickson Irmgard Emmelhainz Mike Hoolboom Gareth James Constanze Ruhm David Rych Gabriële Schleijpen Amie Siegel Jason Simon Caspar Stracke Maija Timonen Kari Yli-Annala Florian Zeyfang CONTENT: 1 Caspar Stracke (ed.) Artists on Godardian Conceptualism Caspar Stracke | Introduction 13 precursors Jason Simon | Review 25 Gabriëlle Schleijpen | Cinema Clash Continuum 31 counterparts Gareth James | Not Late. Detained 41 Florian Zeyfang | Dear Aaton 35-8 61 Francois Bucher | I am your Fan 73 succeeding militant cinema Chto Delat | What Does It Mean to Make Films Politically Today? 83 Irmgard Emmelhainz | Militant Cinema: From Internationalism to Neoliberal Sensible Politics 89 David Rych | Militant Fiction 113 jlg affects Mike Hoolboom | The Rule and the Exception 121 Caspar Stracke I Intertitles, Subtitles, Text-images: Godard and Other Godards 129 Nimetöna Nolla | Funky Forest 145 Lee Ellickson | Segue to Seguestration: The Antiphonal Modes that Produce the G.E. 155 contemporaries Amie Siegel | Genealogies 175 Constanze Ruhm | La difficulté d‘une perspective - A Life of Renewal 185 Maija Timonen | Someone To Talk To 195 Kari Yli-Annala | The Death of Porthos 205 biographies 220 previous page: ‘Aceuil livre d’image’ at Hotel Atlanta, Rotterdam, colophon curated by Edwin Carels, IFFR 2019. Photo: Edwin Carels 225 CASPAR STRACKE INTRODUCTION “Pourquoi encore Godard? A question I was asked many times in the course of producing this edited volume. And further: “Wouldn’t this be an appropriate moment in history to pass the torch?” 13 Most likely there is no more torch to pass. -

Theatricality and French Cinema : the Films of Jacques Rivette

THEATRICALITY AND FRENCH CINEMA: THE FILMS OF JACQUES RIVETTE By MARY M. WILES A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 Copyright 2002 by Mary M. Wiles ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the concern and support of many people. I wish to express my sincerest thanks to my advisor, Maureen Turim, whose intellectual guidance and firm belief in this project made its completion possible. Any intellectual rigor that this project possesses is due to her vigilance. Her exhaustive knowledge of French theater, continental film and literary theory, and film history' provided the touchstone of this project; her open and receptive spirit allowed me the freedom to stage my own ideas. Her constant presence in my life as a feminist, a film scholar, and a most demanding editor was critical to my personal and professional growth. I would also like to thank the members of my supervisory committee, who contributed to the development of this dissertation in numerous w'ays: Robert Ray for his dynamic teaching style in his course, “Taylorism, Metaphysics, and the Movies,” and for his scholarly advice, which has been of great help in my professional growth; Scott Nygren for his acute intelligence and warm encouragement; Susan Hegeman for her untiring support and constructive comments; and finally, Nora Alter, whose knowledge of theories of theater gave me fresh insight and imbued me with a new energy at the final stage of the dissertation. -

Le Chef D'œuvre De Jacques Rivette En Version Restaurée

LE CHEF D’ŒUVRE DE JACQUES RIVETTE EN VERSION RESTAURÉE ! JULIET BERTO DOMINIQUE LABOURIER BULLE OGIER MARIE-FRANCE PISIER mise en scène JACQUES RIVETTE 17 FILMOGRAPHIE DE JACQUES RIVETTE Le coup du berger (cm) • Paris nous appartient • La religieuse • JeanRenoir le patron • L’amour fou • Out 1 : Noli me tangere (durée 12h40 - en co- réalisation avec Suzanne Schiffman) • Out 1 : Spectre (version courte) • Céline et Julie vont en bateau • Duelle • Noroît • Merry-go-round • Le pont du nord Paris s’en va • L’amour par terre • Hurlevent • La bande des quatre • La belle noiseuse • Divertimento (version courte de “La belle noiseuse”) • Jeanne la Pucelle : les batailles • Jeanne la pucelle : les prisons • Haut bas fragile • Une aventure de Ninon • Secret défense • Va savoir • Va savoir + • Histoire de Marie et Julien • Ne touchez pas la hache • 36 vues du Pic Saint-Loup 18 FILMOGRAPHIE DE JULIET BERTO (1947-1990) Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle de Jean-Luc Godard • Week-end de Jean-Luc Godard • La Chinoise de Jean-Luc Godard • Juliet dans Paris de Claude Miller • Roue des cendres de Peter Emmanuel Goldman • Le Gai Savoir de Jean-Luc Godard • Slogan de Pierre Grimblat • Vladimir et Rosa de Groupe Dziga Vertov • Un été sauvage de Marcel Camus • Out 1 de Jacques Rivette Camarades de Marin Karmitz • La Cavale de Michel Mitrani • Camille ou la comédie catastrophique de Claude Miller • Sex-shop de Claude Berri Les Caïds de Robert Enrico • Le Retour d’Afrique de Alain Tanner • Erica Minor de Bertrand van Effenterre • Défense de savoir de Michel -

Fantasmatic Genealogies of the French and American New Waves

The Mid-Atlantic: Fantasmatic Genealogies of the French and American New Waves By Jonathan Everett Haynes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Kaja Silverman, Co-Chair Professor Kristen Whissel, Co-Chair Professor Jeffrey Skoller Professor Nicholas Paige Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Jonathan Everett Haynes 1 Abstract The Mid-Atlantic: Fantasmatic Genealogies of the French and American New Waves by Jonathan E. Haynes Doctor of Philosophy in Film & Media University of California, Berkeley Professors Kaja Silverman and Kristen Whissel, Co-Chairs This dissertation re-imagines the contexts for the paradigmatic film movement of the sixties. The French New Wave, I argue, was made and remade in translation, as texts circulated among French and American scholars, critics, and filmmakers. Subtending this circulation was a genealogical fantasy, with deep roots in the 19th century of Charles Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe. The Baudelaire-Poe liaison has become the defining symbol of la rencontre franco-américaine and is often invoked to characterize the transformative effects of Truffaut's and Godard's politique des auteurs on the reputations of key American filmmakers, like Howard Hawks and Nicholas Ray. Ambiguously connected to official traffic between the two nations, and manifest in a decades-long labor of translation that Baudelaire himself compared to prayer, l'affaire Baudelaire-Poe illuminates the degree to which French-American exchange was transferential. In Poe, Baudelaire saw the reflection of his own desire, and he spent the last years of his life making Poe's work his own. -

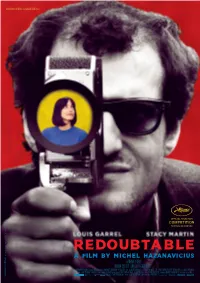

LE REDOUTABLE DP A5.Indd

LES COMPAGNONS DU CINEMA AND LA CLASSE AMERICAINE PRESENT PHOTOS: © PHILIPPE AUBRY – LES COMPAGNONS DU CINÉMA. © LES COMPAGNONS DU CINÉMA – LA CLASSE AMÉRICAINE – STUDIOCANAL – FRANCE 3. DU CINÉMA – LA CLASSE © LES COMPAGNONS DU CINÉMA. – LES COMPAGNONS AUBRY © PHILIPPE PHOTOS: BÉRÉNICE BÉJO MICHA LESCOT GREGORY GADEBOIS LES COMPAGNONS DU CINEMA ET LA CLASSE AMERICAINE PRÉSENTENT LOUIS GARREL STACY MARTIN " LE REDOUTABLE " UN FILM DE MICHEL HAZANAVICIUS AVEC BÉRÉNICE BÉJO MICHA LESCOT GREGORY GADEBOIS FELIX KYSYL ARTHUR ORCIER SCÉNARIO MICHEL HAZANAVICIUS D’APRÈS L’OUVRAGE DE ANNE WIAZEMSKY " UN AN APRÈS " PARU AUX EDITIONS GALLIMARD UNE COPRODUCTION LES COMPAGNONS DU CINÉMA LA CLASSE AMERICAINE FRANCE 3 CINÉMA STUDIOCANAL COPRODUCTEUR WIN MAW / FOREVER GROUP AVEC LA PARTICIPATION DE CANAL + DE FRANCE TÉLÉVISIONS AVEC LE SOUTIEN DE LA RÉGION ILE-DE-FRANCE VENTES INTERNATIONALES WILD BUNCH LES COMPAGNONS DU CINÉMA AND LA CLASSE AMÉRICAINE PRESENT 2017 | France | 1h47 | 4K | 1/85 | 5.1 French release : September 13th, 2017 INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PR Wild Bunch Ryan Werner / +1 917 254 7653 4, Bd de la Croisette [email protected] Hilda Somarriba / +1 323 633 7079 Fanny Beauville [email protected] [email protected] Emilie Spiegel / +1 516 524 9392 [email protected] photos and press kit can be downloaded from: http://www.wildbunch.biz/movie/redoubtable/ SYNOPSIS Paris 1967. Jean-Luc Godard, the most renowned filmmaker of his generation, is shooting La Chinoise with the woman he loves, Anne Wiazemsky, 20 years his junior. Happy, in love, magnetic, they marry. But the film’s reception unleashes a profound self-examination in Jean-Luc. The events of May ‘68 will amplify this process, and the crisis that shakes Jean-Luc will change him profoundly, from star director to Maoist artist outsider, as misunderstood as he is impossible to understand. -

The Depiction of Late 1960'S Counter Culture in the 1968 Films of Jean-Luc Godard

The Depiction of late 1960's Counter Culture in the 1968 Films of Jean-Luc Godard Gary Elshaw A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA in Film, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, November 2000. 2 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4-14 Le Gai Savoir 15-44 Cinétracts 45-68 One Plus One/Sympathy for the Devil 69-79 One AM/One PM 80-93 Un Film Comme les Autres 94-118 Conclusion 119-125 Bibliography 126-130 Filmography 131-139 Appendix 140-143 3 Acknowledgements There are an inordinate number of people to thank for this project. My supervisor, Dr. Russell Campbell, for advice, guidance and the patience and fortitude to put up with my mid- afternoon ramblings. Dr. Harriet Margolis for intellectual and physical sustenance over the couple of years that this project slowly percolated on through. Andrew Brettell for keeping my sense of humour intact. Dr. Lorna McCann for patience, understanding and a sense of humour. Diane Zwimpfer, I owe you many, many thanks, but especially I thank you for helping me to keep sane throughout this and being there for me. My family, who also contributed in so many ways I can't really begin to explain: Brad, Lis, Richard, Renée, Tony, Emma, Mike, Alta, Adrian, Shaye, Clare, Chris, Jon, Rod, Jenny, Mel, Hamish, Steve, Col, Pete, Kay and Muriel, I thank you for keeping me clothed, fed, housed, supported, and most of all--Loved. For putting up with the erratic moods, the continual talk about Godard until you were all bored to death, and the presence of mind to tell me when to shut up. -

Jean-Luc Godard Season – Complete Listings

JEAN-LUC GODARD SEASON – COMPLETE LISTINGS IN CONVERSATIONS, EVENTS AND TALKS Bande à part + Q&A with Anna Karina France 1964. Dir Jean-Luc Godard. With Claude Brasseur, Anna Karina, Sami Frey. 96min. Digital. EST. PG. A BFI release This energetic adaptation of pulp fiction writer Dolores Hitchens’ Fool’s Gold follows the fortunes of an incompetent trio of amateur crooks whose plans to burgle a rich old lady go tragicomically wrong. But the tone is light and the film includes two classic examples of the sheer fun of making movies: the Madison dance scene and the sprint through the Louvre. SAT 16 JAN 15:10 NFT1 Le Mépris Contempt + Introduction with Anna Karina France-Italy 1963. Dir Jean-Luc Godard. With Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang. 103min. Digital. EST. 15. A BFI release A sumptuously stylish study of a rocky marriage and fraught professional relationships, Godard’s unusually straightforward adaptation of a novel by Moravia is also his most hauntingly beautiful film A scriptwriter (Piccoli) adapting Homer’s Odyssey is torn between the demands of a philistine producer (Palance), his loyalty to the director (Lang) and his own self-respect; to make matters worse, his indecision is getting to his wife (Bardot)... Making the most of Raoul Coutard’s luscious ’Scope images and Georges Delerue’s achingly lovely score, Godard ensures that we care about this troubled couple even as he illuminates, with incisive wit, the corrosive compromises often inherent in filmmaking. A monumental achievement which combines the classical with the radical. SAT 16 JAN 17:50 NFT1 Vivre sa vie + Q&A with Anna Karina France 1962.