2002 Calgary Homelessness Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement of Rodney J. Bosco Navigant Consulting, Inc. On

STATEMENT OF RODNEY J. BOSCO NAVIGANT CONSULTING, INC. ON THE “THE FUTURE OF MONEY: COIN PRODUCTION” BEFORE THE HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES SUBCOMMITTEE ON DOMESTIC MONETARY POLICY & TECHNOLOGY UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES APRIL 17, 2012 Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, my name is Rodney Bosco and I am a Director in the Disputes and Investigations practice at Navigant Consulting, Inc. (“Navigant”). I am pleased to testify today concerning our coin system, its cost drivers, and an analysis we conducted recently that identified approximately $200 million in annual cost savings if the United States moved to a steel‐based composition for our vended nickel, dime, and quarter. Navigant is an international consulting firm that provides independent, objective analysis of and opinions on accounting, financial and economic issues. Our report was commissioned by Jarden Zinc Products, North America’s leading plated coin blank producer and a licensee of the Royal Canadian Mint’s multi‐ply plated steel technology. We acknowledge the significant assistance of the Royal Canadian Mint (“RCM”) and Worthington Industries in the preparation of our analysis. As the Subcommittee examines ways to make our coins less expensively, and awaits the United States Mint’s recommendations on alternative metals later this year, our work has led us to three major conclusions which I want to share with you today. (1) Adoption of a multi‐ply plated steel composition for the vended five‐cent, dime and quarter‐dollar coins will reduce the per‐unit raw material costs of these coins by 84% to 89%, based on recent prices of copper, nickel and low‐carbon steel during the United States Mint’s 2011 fiscal year. -

U.S. & Canadian

U.S. & Canadian Coin Inserts In this free coin insert pack, you'll find: •U.S. coin amount inserts •U.S. coin name inserts •U.S. coins {front and back} with names for penny, nickel, dime, quarter, half dollar, the Sacagawea dollar •U.S. coins {front and back} without names •Canadian coin amount inserts for penny, nickel, dime, quarter, Loonie, and Toonie •Canadian coin name inserts •Canadian coins {fronts} with names •Canadian coins {fronts} without names Make learning about money more HANDS-ON by inserting the coin inserts into your pocket cubes. You can roll and match the coins, names, or amounts! Fun! Be sure to visit This Reading Mama! Terms of Use: This printable pack was created for you to use at home with your child/students or with multiple children in a classroom/tutoring setting. Please do not sell, host, reproduce, giveaway, or store on any other site (including a blog, Facebook, 4Shared, Dropbox, etc.). Thank you! You May Also Like Let’s Connect! Blog: www.thisreadingmama.com Subscribe to my Newsletter: HERE TpT: /This-Reading-Mama Facebook: /thisreadingmama Pinterest: /thisreadingmama Twitter: @thisreadingmama Email: [email protected] U.S. Coin Pocket Cube Inserts www.thisreadingmama.com 1¢ 5¢ Mama Reading ©This www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com 10¢ 25¢ www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com 50¢ $1.00 www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com U.S. Coins Inserts Nickel Penny Mama Reading ©This www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com Dime Quarter www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com Half Sacagawea Name Inserts Name - Dollar Dollar www.thisreadingmama.com www.thisreadingmama.com U.S. -

Crude Optimism Romanticizing Alberta’S Oil Frontier at the Calgary Stampede Kimberly Skye Richards

Crude Optimism Romanticizing Alberta’s Oil Frontier at the Calgary Stampede Kimberly Skye Richards An immaculate young woman regally waves at a sea of enthusiastic fans. Perched on her head is a white cowboy hat embellished with a tiara that has “Calgary Stampede Queen” written on it in rhinestones. She is a vision of “westernness” in cowboy boots, a buckskin skirt and jacket, and turquoise jewels. Her express purpose this hot July afternoon is to welcome the 115,000 folks attending the “Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth,” the Calgary Exhibition and Stampede. She is a “welcome figure,”1 like those white-cowboy-hat-wearing individuals in the Calgary air- port who stand in the arrivants’ path and greet travelers. These performances of western hospi- tality amount to a performance of power: the assertion of settler rights to land.2 They are just 1. I borrow this term from Stó:lō scholar Dylan Robinson’s essay “Welcoming Sovereignty,” which examines Indigenous sovereignty and gestures of welcome that take place in spaces of transit and gathering (2016:24). 2. In using the term “settler” to describe non-Indigenous people living in western Canada, I am referring to the idea within settler colonial studies that being a settler is not an identity, but a structural position and experience of power and privilege. Settlers settle into land appropriated by imperial nations and create independent homelands for themselves. They are defined by conquest; they are “founders of political orders and carry their sovereignty TDR: The Drama Review 63:2 (T242) Summer 2019. ©2019 138 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/dram_a_00839 by guest on 26 September 2021 Student Essay Contest Winner Kimberly Skye Richards is a PhD Candidate in Performance Studies at the University of California-Berkeley. -

The 1969 Large Date Ten Cents

The 1969 Large Date Ten Cents by Jeremy Day This is the story of the incredibly rare 1969 Large Date ten cents - a coin so rare that its very existence was not confirmed until nine years after it was struck! The first hint of this coin's existence came in 1970 when a woman walked into Peter Degraaf's coin store in Ottawa and showed him a 1969 Large Date ten cent piece she had found in her change. She inquired about its rarity and possible value, but Peter, never having seen one, could not verify its worth. The woman then left without giving her name or phone number. She never returned. But. Peter recognized that the coin was important for the reason that the old 1953-1968 reverse die had been used to produce a 1969 ten cent coin, when the nor mal production of 1969 ten cent coins showed an entirely remodelled schooner, date and devices, all of which are significantly smaller in style than the older type. Peter reasoned that the 1968 and earlier reverse master die had had the date repunched to read 1969. In such a case, one would expect several working dies, and thus large quantities of the 1969 large date, large schooner type. So Peter started checking around to find out what had happened at the Royal Canadian Mint to produce these coins. Were they trial coins and if so, how did they get into circulation? Were they knowingly produced and released for general circulation? If so, how many dies were made and what "".il~ the mintage? Were they "back door jobs"? If so, why would the perpetrator spenc them, and where were they all? Had anyone else seen or heard of any? Peter tried to get information from the Royal Canadian Mint in vain. -

Canadian Money

Canadian Money Grades 1 to 2 Written by Leanne Howse Learning how to count money is an important skill as we need money to buy some of our favourite things! This resource is packed with worksheets and activities that allow students to practice important concepts involving money to meet expectations of the grade 1 and 2 Ontario Mathematics Curriculum. Concepts covered include: identifying Canadian coins and their value; representing money amounts in one or more ways; counting on to find the total value of a collection of coins; adding and subtracting money amounts; solving problems involving money. Assessments that can be used at the end of the math unit are included for each grade along with a marking rubric. Leanne Howse has been teaching since 1999. Although she has had experience in all elementary grades, she has found true joy in teaching primary students. She currently teaches grade 1/2. Although teaching is her passion, she enjoys creating resources that other teachers can use in their classrooms. She resides in Delhi, Ontario with her husband and 2 children. Copyright © On The Mark Press 2015 This publication may be reproduced under licence from Access Copyright, or with the express written permission of On The Mark Press, or as permitted by law. All rights are otherwise reserved, and no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, except as specifically authorized. “We acknowledge the -

Collecting America the Beautiful 5 Ounce Silver

Liberty Coin Service Collecting America The Beautiful 5 Ounce Silver Quarters by Thomas Coulson The Statehood Quarter program which ran from 1999 to 2009 was im- mensely popular. It introduced millions of new collectors to numismat- ics. These new collectors were searching their change for the latest issues and eagerly awaiting the release of the quarter from their home state. As a result of this success, Congress authorized a new series of commem- orative quarters honoring important sites in each of the fifty states and six territories and possessions. The new coins were introduced under the title America the Beautiful Quarter Series. They were also known by the abbreviation ‘ATB’. The coins were first issued in 2010, and five sites were honored each year and will continue to be through 2021. There 2010 Mount Hood, Oregon are two main themes for the issues: Natural wonders and Historic sites. 5 Ounce Silver Quarter The America the Beautiful Quarter series is an intriguing collection to assemble. The coins promote awareness of so much of the Nation’s natural grandeur and its hallowed grounds. De- sign lessons the Mint learned from the Statehood Quarter series were applied to the new coins. The America the Beautiful coins are more aesthetically pleasing than the earlier Statehood quarters because of their common border design and more specific subject matter. While the State Quarters could encompass many different types of themes, the America the Beautiful Quarters had specific subjects assigned for each state before the design process. At their best, the designs are innovative and alluring. The Mount Hood, Statehood Quar- ter Obverse Denali, Hawai’i, and White Mountain issues are great examples of modern numismatic art. -

![Activity 1: History of Canadian Money and Crossword [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3758/activity-1-history-of-canadian-money-and-crossword-pdf-2723758.webp)

Activity 1: History of Canadian Money and Crossword [PDF]

MODULE 1: Money—Earn it! Session 1: Introduction and expectation setting Reading: History of Canadian Money Source: www.thecanadaguide.com/basics/money From the 1800s to Today In early Canadian history, people in Britain’s Canadian colonies used a variety of different currencies to buy things, including British pounds, American dollars, Spanish pesos, and even unique colonial currencies made by local banks and governments. In 1867, the new unified Canadian government gained exclusive constitutional power over currency, and in 1870 it used this power to pass the Dominion Notes Act (now known as the Currency Act) which made the Canadian Dollar ($) the official currency of Canada. A Canadian dollar is made up of 100 Canadian cents (¢). Originally tied to value of the British pound, and then the price of gold, since 1931 the Canadian dollar has been a so-called “free-floating” currency with a value determined by the international marketplace. Like most advanced countries, Canada also has a national bank, known as the Bank of Canada, that has the power to both print and buy currency in order to help control the currency’s value. In the opinion of the International Monetary Fund, the Canadian dollar is one of the world’s seven reserve currencies known for its stability and reliability even in times of economic uncertainty. Loonie (one dollar) The Loonie is a large coin made of gold-coloured nickel. There used to be a one-dollar bill, but it was phased out in the 1980s. The coin is called a “Loonie” because it has a picture of a loon, the national bird of Canada, on it. -

Date and Mint Mark

Littleton’s Illustrated Guide to Mint Marks on Regular-Issue U.S. Coins Philadelphia: Mint mark “P” – coinage Carson City: Mint mark “CC” – coinage New Orleans: Mint mark “O” – coinage years 1793 to date. Since this was the first years 1870-1893. Named after the famous years 1838-1861, 1879 to 1909. U.S. Mint and has always been the main frontiersman Kit Carson, this intriguing Nicknamed the “Crescent City” for its facility, most coins from historic Philadelphia have no capital city of Nevada was chosen as a mint location location stretching around a bend in the Mississippi mint mark. Exceptions are the Wartime nickels of because of its nearness to such rich silver mines as the River, fascinating New Orleans was the site of a branch 1942-45 (shown), Anthony dollars of 1979-81, and Comstock Lode of Virginia City, Nevada. mint which handled bullion ore from southern mines. all other Philadelphia coins after 1979 except the cent. Note: “C” mint mark gold coins were struck from After closure, the building lay vacant until converted to 1838-61 at Charlotte, North Carolina. a museum and art center. Denver: Mint mark “D” – coinage San Francisco: Mint mark “S” – About Mint Mark Punches: Until the 1990s, dies for branch mints were hand-punched with the mint mark, and the years 1906 to date. Establishment of a coinage years 1854 to 1955, 1968 to size and location of the mint mark varied depending on where Denver Mint was the natural result of major date. The mint facility in this romantic and how deeply the punch was impressed. -

Canadian Currency Literacy Skill-Building Resource

Canadian Currency Literacy Skill-Building Resource Introduction: This resource was created to supplement real-world tasks in food, shopping, banking or any other themes and modules where using Canadian currency is required. These worksheets are not organized by CLB level or in a specific order. Feel free to use what you would like and disregard any worksheets or activities that do not pertain to your learners or learning outcomes. These activities are not meant to be stand alone; all required numeracy concepts likely require presentation and/or introduction by the instructor and further supplemental practice activities are recommended. These worksheets and activities aims to help develop numeracy skills in the category of “Money Concepts” as outline in ESL for Adult Literacy Learners (ALL) (2014, Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks). Please see pg. 3 for a description of which numeracy skills match each activity. Feel free to modify any particular worksheets for your educational, non- commercial in-class use but do not publish, host or distribute this resource without prior permission from the Literacy Centre of Expertise and The Immigrant Education Society (Calgary, AB, Canada). To request an editable MS Word document contact https://www.immigrant- education.ca/literacycentre/contact/ Created by the Literacy Centre of Expertise at The Immigrant Education Society © 2021 1 Table of Contents Activity pg. Numeracy Skills in Activities 3 Activity 1: Match Coins 4 Activity 2: Match Coins to Photos 5 Activity 3: Match Coins to Values 6 -

VILLAGE COIN SHOP Serving the Numismatic Community Since 1959

2018 - 2019 Catalog Volume 58 VILLAGE COIN SHOP Serving the numismatic community since 1959 COINS, CURRENCY, AND SUPPLIES www.VillageCoin.com 2018 U.S. Gold Eagles Half Dollar Commemoratives • Brilliant Uncirculated All in original box with COA unless noted **In Capsules Only • Call For Prices USGE1 . 1/10 oz Gold Eagle USGE2 . 1/4 oz Gold Eagle USGE3 . 1/2 oz Gold Eagle USGE4 . 1 oz Gold Eagle ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD82B7 . 1982-D Washington . BU . $16 .00 Commemorative Sets CMHD82C8 . 1982-S Washington . Proof . 16 .50 CMHD86B7 . 1986-D Statue of Liberty** . BU . 6 .25 CMHD86C8 . 1986-S Statue of Liberty** . Proof . 5 .00 CMHD91C7 . 1991-D Mount Rushmore . BU . 20 .00 CMHD91C8 . 1991-S Mount Rushmore . Proof . 28 .00 CMHD92C8 . 1992-S Olympic . BU . 35 .00 CMHD92C8 . 1992-S Olympic . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93C8 . 1993-S Bill of Rights . BU . 40 .00 CMHD93C8 . 1993-S Bill of Rights . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD93A7 . 1993-P World War II . BU . 30 .00 CMHD93A8 . 1993-P World War II . Proof . 36 .00 CMHD94B7 . 1994-D World Cup . BU . 12 .50 ITEM DESCRIPTION GRADE PRICE CMHD94A8 . 1994-P World Cup . Proof . 11 .00 Two-Coin Half Dollar And Silver Dollar Sets CMHD95A7 . 1995-P Civil War . BU . 63 .00 CMTC86A7 . 1986 Statue of Liberty . BU . $ 39 .00 CMHD95C9 . 1995-S Civil War . Proof . 63 .00 CMTC86A8 . 1986 Statue of Liberty . Proof . 39 .00 CMHD95C7 . 1995-S Olympic Basketball . BU . 27 .50 CMTC86C8 . 1989 Congressional . Proof . 49 .00 CMHD95C8 . 1995-S Olympic Basketball . Proof . 35 .00 CMHD95C7 . 1995-S Olympic Baseball . BU . -

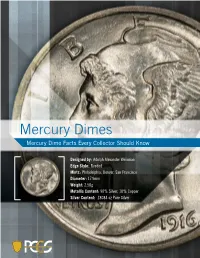

Mercury Dimes Mercury Dime Facts Every Collector Should Know

Mercury Dimes Mercury Dime Facts Every Collector Should Know Designed by: Adolph Alexander Weinman Edge Style: Reeded Mints: Philadelphia, Denver, San Francisco Diameter: 17.9mm Weight: 2.50g Metallic Content: 90% Silver, 10% Copper Silver Content: .18084 oz Pure Silver 2 Mercury Dimes 1916 was a very special year in the history of U.S. coinage. In that year, three new silver coins made their debut, and for the first time in American history, different designs were used on the dime, quarter and half dollar coins. Adolph A. Weinman, who also designed the famed Walking Liberty Half Dollar, designed the Mercury Dime, or Winged Liberty Dime. His monogram “AW” can be found to the right of Liberty’s neck. The mintmark (“D” for Denver, “S” for San Francisco) can be found at the bottom of the reverse, just to the left of the fasces. Mercury Dimes were made through 1945, when a new dime was designed bearing Franklin D. Roosevelt’s image, in response to his death. PCGS.COM 3 Are Mercury Dimes Rare? As a group, Mercury Dimes are not rare. Over 2.5 billion were struck, and even if only 1% survived, that still leaves over 25 million today. During the deepest part of the depression, 1932-1933, no dimes were struck. As a result, collectors today divide Mercury Dimes into the early dates (1916-1931) and late dates (1934-1945). Nearly all of the late dates are common and can be found in roll quantity from online sources such as eBay or from dealers. Enlarged view of monogram shown on obverse of coin. -

The Mountie: from Dime Novel to Disney. by Michael Dawson. (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1998

Document generated on 09/30/2021 4:57 a.m. Ethnologies The Mountie: From Dime Novel to Disney. By Michael Dawson. (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1998. ISBN 1-896357-16-4, pbk.) Kristin Harris Musées Museums Volume 24, Number 2, 2002 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/006653ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/006653ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Association Canadienne d’Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Harris, K. (2002). Review of [The Mountie: From Dime Novel to Disney. By Michael Dawson. (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1998. ISBN 1-896357-16-4, pbk.)]. Ethnologies, 24(2), 256–259. https://doi.org/10.7202/006653ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 256 COMPTES RENDUS / REVIEWS careful to critically examine his sources and to present any potential limitations. While this book focuses on trends and patterns in the development of domestic architecture over a three-century period, Ward is careful to point out the exceptions. He cautions the reader to remember that this development occurred at different paces for different economic levels.