Cert Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1:21-Cv-02006 Document #: 54-1 Filed: 07/15/21 Page 2 of 13 Pageid #:1555

Case: 1:21-cv-02006 Document #: 54-1 Filed: 07/15/21 Page 2 of 13 PageID #:1555 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION PROTECT OUR PARKS, INC., et al. Plaintiffs, No. 1:21-CV-02006 v. Judge John Robert Blakey PETE BUTTIGIEG, SECRETARY OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, et al. Defendants. BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE CIVIC GROUPS IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Craig C. Martin Matt D. Basil Samuel J. Gamer Willkie Farr & Gallagher 300 North LaSalle Chicago, Illinois 60654-3406 (312) 728-9000 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae Civic Committee of the Commercial Club of Chicago, the Chicago Urban League, and the Chicago Community Trust Case: 1:21-cv-02006 Document #: 54-1 Filed: 07/15/21 Page 3 of 13 PageID #:1556 INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE1 Amici curiae Civic Groups are three long-standing and leading Chicago organizations in their respective non-profit fields: the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club of Chicago (“Civic Committee”) is one of the city’s foremost non-profits focused on the business community; the Chicago Urban League (“Urban League”) is among the city’s preeminent non-profits focused on its Black residents; and the Chicago Community Trust (“Community Trust”) (together, “Civic Groups”) is one of the city’s foremost non-profits in the philanthropic sector. Collectively, the Civic Groups have been acting in their leadership roles for over 350 years. As long-standing Chicago non-profit organizations, each of the Civic Groups has contributed to the city’s progress for over a century. -

Contact: Kate Berner, [email protected] Obama

Contact: Kate Berner, [email protected] Obama Presidential Center Economic Impact Assessment Key Findings Today the Obama Foundation released an Economic Impact Assessment that estimates the potential economic impact that the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) will have on the South Side of Chicago, Cook County and the State of Illinois. The economic impact includes both potential jobs created as well as the estimated increase in tax revenue attributed to construction and ongoing operations of the OPC. TOURISM Among the elements that have the most potential to be transformative for the City of Chicago and the South Side is the number of people who will come to visit the Obama Presidential Center (OPC), and, with the right mix of opportunities, stay to explore the South Side. Expected Number of Visitors The OPC is expected to attract 625,000 to 760,000 visitors annually following a period of higher visitorship in the first few years. The first few years after opening the OPC may have significantly higher visitor numbers based on patterns observed at other presidential centers. Furthermore, the range of visitors provided above is a conservative estimate. Because of the historic nature of the Obama presidency, the OPC’s location in an urban area surrounded by other cultural attractions, and its mission to serve as a hub for civic engagement, there is reason to believe the true number of visitors could be significantly higher. JOB CREATION More than just a museum, the Obama Presidential Center intends to serve as a community center and catalyst for local economic development. Phase South Side Jobs Created Cook County Jobs & Income Generated Created & Income (Estimated) Generated (Estimated) Construction 1407 jobs/$86M in 4945 jobs/$296M in additional income additional income Ongoing Operations 2175 jobs/$81M in annual 2536 jobs/$104M in annual income income SUPPORTING CHICAGO’S ECONOMY OPC visitors may generate additional income for local business owners in Chicago and on the South Side. -

What a Biden Harris Administration Could Look Like

President Biden’s Team Confirmed choices of the 46th President Secretary of Secretary of State Secretary of Defense Treasury Antony Blinken Janet Yellen Lloyd Austin Former Deputy Former Chairwoman of Retired General, former Secretary of State the Federal Reserve head of U.S. Central Board Command Secretary of Secretary of Health and Secretary of Agriculture Interior Human Services Deb Haaland Tom Vilsack Xavier Becerra Congresswoman from Former Secretary of Current Attorney Arizona, one of the first Agriculture under General of California Native American Obama, former women elected to Governor of Iowa Congress and the first Native American nominated for a cabinet position Secretary of Housing and Secretary of Secretary of Energy Urban Development Transportation Marcia Fudge Pete Buttigieg Jennifer Granholm Congresswoman from Ohio Mayor of South Bend, Former Governor of and former chair of the IN and former Michigan and previous Congressional Black Caucus presidential candidate front-runner for the position under Obama Secretary of Secretary of Secretary of Veteran Affairs Education Homeland Security Dr. Miguel Cardona Denis McDonough Alejandro Mayorkas Current Commission of Former White House Former Deputy Education for the state Chief of Staff and Secretary of Homeland of Connecticut and Deputy National Security former public school Security Advisor during teacher the Obama Administration President Biden’s Team Confirmed choices of the 46th President EPA Administrator Domestic Climate Czar Michael Regan Gina McCarthy Current Secretary of Former EPA Administrator the North Carolina under the Obama Department of Administration Environmental Quality President Biden’s Team Rumored choices of the 46th President U.S. Attorney Secretary of Secretary of General Commerce Labor Doug Jones Ursula Burns Andy Levin Former Senator from Alabama and former U.S. -

FLEC Public Meeting May 26, 2021 Speaker BIO's

Financial Literacy and Education Commission Public Meeting May 26, 2021 SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Janet L. Yellen, Secretary of the Treasury On January 26, 2021, Janet Yellen was sworn in as the 78th Secretary of the Treasury of the United States. An economist by training, she took office after almost fifty years in academia and public service. She is the first person in American history to have led the White House Council of Economic Advisors, the Federal Reserve, and the Treasury Department. Janet Louise Yellen was born in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn in 1946. Her mother, Anna Ruth, was an elementary school teacher while her father, Julius, worked as a family physician, treating patients out of the ground floor of the family’s brownstone. In 1967, Secretary Yellen graduated from Brown University and went on to earn her PhD at Yale. She was an assistant professor at Harvard until 1976 when she began working at the Federal Reserve Board. There, in the Fed’s cafeteria, she met fellow economist, George Akerlof. Janet and George would marry later that year. They would go on to have a son, Robert, now also an economics professor. In 1980, Secretary Yellen joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley, where she became the Eugene E. and Catherine M. Trefethen Professor of Business and Professor of Economics. She is Professor Emeritus at the university. Secretary Yellen’s scholarship has focused on a range of issues pertaining to labor and macroeconomics. Her work on “efficiency wages” with her husband George Akerlof studied why firms often choose to pay more than the minimum needed to hire employees. -

Biden Cabinet Candidates and Senior White House Positions 4835-4287-3297 V.4.Xlsx

Nominated/Appointed Favored Department Name Description Rep. Cheri Bustos Congresswoman from Illinois; former member of East Moline, Ill. City Council Rep. Marcia Fudge Congresswoman from Ohio; former mayor of Warrensville Heights, Ohio Krysta Harden Former Deputy Agriculture Secretary Senior Fellow in International and Public Affairs at Brown University’s Watson Institute; former senator from North Dakota; former North Dakota attorney Heidi Heitkamp general Amy Klobuchar Minnesota senator; former prosecutor in Minneapolis and candidate for the Democratic nomination AGRICULTURE Kathleen Merrigan Former deputy Agriculture Secretary Collin Peterson Representative from Minnesota and House Agriculture Committee Chairman Chellie Pingree Representative from Maine Karen Ross Former Chief of Staff to Obama Secretary of Agriculture Michael Scuse Delaware Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack Former Iowa governor who served as agriculture secretary for Mr. Obama Xavier Becerra California attorney general; former California congressman and state Assembly member Preet Bharara Former US Attorney for the Southern District of NY Merrick Garland Federal appeals court judge Jeh Johnson Former Obama Homeland Security Secretary ATTORNEY GENERAL/ Doug Jones Alabama senator; former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama JUSTICE Lisa Monaco Former chief counterterrorism and homeland security advisor to Obama Deval Patrick Former Massachusetts Governor Tom Perez Chair of the Democratic National Committee; former secretary of Labor; former assistant attorney general for civil rights Sally Yates Partner, King and Spalding; former acting attorney general and deputy attorney general; former U.S. attorney in the Northern District of Georgia CIA David Cohen Former Deputy CIA Director CLIMATE ENVOY John Kerry Former Secretary of State Jared Bernstein Biden Economic Advisor Heather Boushey Economist Rep. -

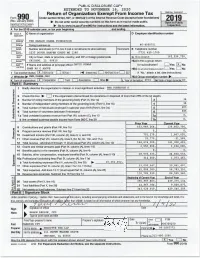

7/13/20 Public Disclosure Copy

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY 7/13/20 Form 990 (2019) THE BARACK OBAMA FOUNDATION 46-4950751 Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III X 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission: SEE SCHEDULE O 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 23,167,927. including grants of $ 1,010,000. ) (Revenue $ -21,268. ) OBAMA FOUNDATION PROGRAMMING: IN SERVICE OF THE FOUNDATION'S MISSION TO INSPIRE, EMPOWER, AND CONNECT PEOPLE TO CHANGE THEIR WORLD, THE FOUNDATION CONTINUED TO WORK WITH YOUNG LEADERS IN A VARIETY OF LOCAL, NATIONAL, AND GLOBAL PROGRAMS. FELLOWS: THE OBAMA FOUNDATION FELLOWSHIP SUPPORTS OUTSTANDING CIVIC INNOVATORS -- LEADERS WHO ARE WORKING WITH THEIR COMMUNITIES TO CREATE TRANSFORMATIONAL CHANGE, ADDRESSING SOME OF THE WORLD'S MOST PRESSING PROBLEMS. IN 2019, THE PROGRAM WELCOMED 20 NEW COMMUNITY-MINDED RISING STARS FROM AROUND THE WORLD FOR A TWO-YEAR, NON-RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM, DESIGNED TO AMPLIFY THE IMPACT OF THEIR WORK AND INSPIRE A WAVE OF CIVIC INNOVATION. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:21-cv-02006 Document #: 48 Filed: 07/15/21 Page 1 of 47 PageID #:1474 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION PROTECT OUR PARKS, INC., et al. ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Case No. 21 CV 2006 ) PETE BUTTIGIEG ) Judge John Robert Blakey SECRETARY OF THE U.S. ) DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, ) et al. ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OF LAW OF DEFENDANT THE BARACK OBAMA FOUNDATION IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Case: 1:21-cv-02006 Document #: 48 Filed: 07/15/21 Page 2 of 47 PageID #:1475 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................5 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................................8 I. Plaintiffs Are Unlikely to Succeed on the Merits. ...........................................................9 II. Plaintiffs Cannot Establish Irreparable Harm. ...............................................................10 A. Plaintiffs’ Delay Undermines Their Claims of Irreparable Harm. ............................10 B. Plaintiffs’ Claim of Procedural Harm Is Insufficient as a Matter of Law. ................12 C. Plaintiffs Fail to Support Their Claim of Organizational Harm. ...............................12 D. Plaintiffs Fail To Support -

Reclaiming Democracy

RECLAIMING DEMOCRACY GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE SAN FRANCISCO BAY | APRIL 1–3 RECLAIMING DEMOCRACY GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 1–3, 2 19 SAN FRANCISCO BAY 2019 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2019 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Minor adjustments have been to remarks for clarity. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team— Meghan Kennedy, Angelina Donhoff, Suzy Antounian, Claire McMahon, Carla Thorson, Julia Levin, Taytum Sanderbeck, Jarrod Sport, Laura Beatty, Sylvia Hacaj, Isaac Mora, and Lucia Johnson Seller—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Anonymous Newman’s Own Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation The David & Lucile Packard Margaret A. Cargill Foundation Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Sall Family Foundation World Bank Group SUPPORTING MEMBERS African Development Fund MEMBERS The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley William Draper III Charitable Trust Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Felipe Medina Humanity United Inter-American Development Bank International Finance Corporation MacArthur Foundation The MasterCard Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

August 2021 Law Review 1 Standing to Challenge

AUGUST 2021 LAW REVIEW STANDING TO CHALLENGE OBAMA CENTER IN CHICAGO PARK James C. Kozlowski, J.D., Ph.D. © 2021 James C. Kozlowski Contrary to popular opinion, the jurisdiction of the courts, particularly federal courts, is actually quite limited. The judiciary does not have the power or authority to address, let alone provide legal redress, for every individual grievance or perceived social ill. Resolution of policy disputes and political questions are typically the responsibility of elected representatives in the legislative and executive branches of government, not the judiciary. As illustrated by the case described herein, the standing requirement oftentimes poses a significant procedural hurdle for citizen activists to have a federal court consider a challenge to a local government project which diverts park resources to other uses. In the case of Protect Our Parks, Inc. v. Chicago Park District, 971 F.3d 722 (10th Cir. 8/21/2020), Plaintiff Protect Our Parks and several individual Chicago residents (POP) sued the Defendants City of Chicago and the Chicago Park District (City) to halt construction of the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago's Jackson Park. Unhappy with the environmental and financial impact of the project, POP brought a number of federal and state claims which essentially contended "the Obama Presidential Center does not serve the public interest, but rather the private interest of its sponsor, the Barack Obama Foundation." (This opinion from the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit was written by Judge Amy Coney Barrett prior to her nomination and confirmation as an associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States.) OBAMA CENTER USE AGREEMENT First developed as the site for the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, Jackson Park has a storied place in Chicago history, and as public land, it must remain dedicated to a public purpose. -

What a Biden Harris Administration Could Look Like

President Biden’s Team Confirmed choices of the 46th President Secretary of Secretary of State Secretary of Defense Treasury Antony Blinken Janet Yellen Lloyd Austin Former Deputy Former Chairwoman of Retired General, former Secretary of State the Federal Reserve head of U.S. Central Board Command Secretary of Attorney General Secretary of Agriculture Interior Merrick Garland Deb Haaland Tom Vilsack Currently the United Congresswoman from Former Secretary of States Court of Appeals Arizona, one of the first Agriculture under for DC and former Native American Obama, former Obama nominee to the women elected to Governor of Iowa Supreme Court Congress and the first Native American nominated for a cabinet position Secretary of Health and Secretary of Labor Secretary of Commerce Human Services Gina Riamondo Marty Walsh Xavier Becerra Current Governor of Current Mayor of Boston Current Attorney and former Union leader Rhode Island and General of California former VP candidate Secretary of Housing and Secretary of Secretary of Energy Urban Development Transportation Marcia Fudge Pete Buttigieg Jennifer Granholm Congresswoman from Ohio Mayor of South Bend, Former Governor of and former chair of the IN and former Michigan and previous Congressional Black Caucus presidential candidate front-runner for the position under Obama President Biden’s Team Confirmed choices of the 46th President Secretary of Secretary of Secretary of Veteran Affairs Education Homeland Security Dr. Miguel Cardona Denis McDonough Alejandro Mayorkas Current Commission of -

Building Strong Communities Obama Foundation Event Aims to Empower Next Generation of Leaders / Pg

today.uic.edu July 11 2018 Volume 37 / Number 35 today.uic.edu For the community of the University of Illinois at Chicago Building strong communities Obama Foundation event aims to empower next generation of leaders / pg. 3 Photo: Jenny Fontaine Daily fasting East Meets Gilman Softball player works for West highlights scholars study named league weight loss collaborations abroad this scholar-athlete summer of season 5 6-7 11 12 Facebook / uicnews Twitter / uicnews YouTube / uicmedia Instagram / thisisuic & uicamiridis 2 UIC News | Wednesday, July 11, 2018 today.uic.edu UIC News | Wednesday, July 11, 2018 3 Obama Foundation hosts Community Conversation at UIC By Carlos Sadovi — [email protected] With University of Illinois at Chicago ship, it must be here,’” Simas said. Chancellor Michael Amiridis standing Amiridis said that UIC’s relationship alongside him before hundreds of grass- with the foundation was a strong one built roots leaders, Obama Foundation CEO on many “common values” that the uni- David Simas recalled how the former versity has maintained throughout the president told him in 2016 that his best last 50 years. work was still to come. “We also have a common desire for That work, creating stronger commu- change and opportunity,” Amiridis said. nities, was on display Tuesday at the Isa- “This institution (UIC) was created by and dore and Sadie Dorin Forum at UIC, where for the people of Chicago, and it was cre- the foundation hosted the Chicago Com- ated on the principles of public service, munity Conversation. civic engagement -

5894 Cullinane and Ellis.Indd

Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organization Michael Patrick Cullinane & Sylvia Ellis, 2018 © the chapters their several authors, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 4744 3731 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3733 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3734 9 (epub) The right of Michael Patrick Cullinane and Sylvia Ellis to be identifi ed as the editors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55894_Cullinane894_Cullinane aandnd EEllis.inddllis.indd iivv 004/10/184/10/18 33:38:38 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vii Notes on Contributors viii An introduction to presidential legacy 1 Michael Patrick Cullinane and Sylvia Ellis 1. Presidential temples: America’s presidential libraries and centers from the 1930s to today 11 Benjamin Hufbauer 2. Presidential legacy: A literary problem 26 Kristin A. Cook 3. Pennsylvania Avenue meets Madison Avenue: The White House and commercial advertising 55 Michael Patrick Cullinane 4. Eisenhower’s Farewell Address in history and memory 76 Richard V.