Socially Constructed Environmental Issues and Sport: a Content Analysis of Ski Resort Environmental Communications Sam Spector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, Let’s build a bridge - a bridge to the future. Like any bridge designed to stand the test of time, our bridge needs a strong foundation. LETTER FROM BOARD OF At Team Summit Colorado, our mission promotes a strong foundation in DIRECTORS - our athletes by elevating their sense of responsibility, integrity, and ex- cellence while they pursue their personal best in their chosen athletic PRESIDENT discipline. We believe these values provide direction and purpose to the whole athlete youth who participate in our programs. By providing the whole team opportunity to succeed on and off the mountain, whole community our athletes will grow to be- come outstanding individuals, supportive team members, and the future leaders in their communities. The lessons they learn along the way build a foundation for the bridge to the future. We welcome you to join us as we build this bridge. Jay Long Board President Dear Friends, U14’s in North America. Other highlights were the many podiums at LETTER FROM both the Age Class and Youth Ski League races, proof that TSC has a The last twelve months at Team very bright future. EXECUTIVE Summit Colorado (TSC) have been a time of rebuilding, growth, invest- The past season saw a revamping of programs, as we fully committed DIRECTOR ment, community awareness and overall to providing competitive programs that will enable our athletes to accomplishments. To start the fiscal year, elevate and reach their personal podiums. For those competing in li- we began investing in our future by hiring an censed events, we provided the opportunity to train a minimum of two Office Manager and a Business Development days per week for little or no additional cost to the family. -

Loyalty Programs Hit the Ski Hills Industry Analysis from Ideaworks

Issued: December 3, 2004 Contact: Jay Sorensen For inquiries: 414-961-1939 Powder and Points – Loyalty Programs Hit the Ski Hills Industry Analysis from IdeaWorks The ski industry embraces airline-style frequent customer programs at 11 of the 20 largest U.S. ski areas. Frequent-skier programs offered by major ski areas are far more generous and consumer friendly than their airline industry counterparts: • Squaw Valley offers a free lift ticket for every four purchased - - an amazing return of 25%. • The PEAK Rewards program associated with Breckenridge Ski Resort allows up to 8 family members to pool their points into one account. • PEAK Rewards also allows the exchange of points and airline miles with Frontier’s EarlyReturns frequent flier program. • The Vertical Plus program offered by the Northstar-at-Tahoe ski area is most unusual because its members accrue benefits based upon the vertical feet on ski runs taken by its members. Each program has its unique qualities – - yet they are very similar on the issue of reward restrictions. Leaving the inventory restrictions and black-out dates of the airline industry behind, these frequent skier programs allow members to redeem rewards for free lift tickets on the busiest of holiday weekends. Where the programs seem to lag their airline-industry counterparts is in areas involving bonus partners, co-branded credit cards, elite customer recognition and year-round participation. Frequent-Skier Programs at the 20 Largest U.S. Ski Areas IdeaWorks reviewed the frequent-skier programs associated with the 20 largest U.S. ski areas as determined by “2003 season skier visits” data compiled by the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA). -

Past Summer Ops Camp Attendance

Past Summer Ops Camp Attendance Alta Jiminy Peak Andacor S.A. Keystone Resort Antelope Butte Killington Resort Arapohoe Basin Kläppen Ski Resort, Sweden Asessippi Ski Area & Resort Las Vega Ski & Snowboard Resort Aspen Skiing Company Le Massif Le Charlevoix Association for Challenge Loon Mountain Course Tech. Massanutten Resort Attitash Mont Sutton Bear Creek Mount Hernon Adventure Program Big Bear Mountain Resorts Mount Hood Ski Bowl Snow King Mountain Resort Blue Mountain Mount Snow Snow Valley, AB Bogus Basin Mountain Mount Sunapee Resort Snow Valley, CA Recreation Area Mountain Creek Snowbasin Boler Mountain Mt Baldy Resort Snowbird Boy Scouts of America Mt Seymour Resorts Snowshow Mountain Boyne Highlands Mt. Hood Meadows Soaring Eagle, Inc. Boyne Resorts Nashoba Valley Ski Area Station Massif du Sud Breckenridge Resort National Ability Center Steamboat Ski & Resort Corporation Bretton Woods Nemacolin Woodlands Sterling Vinyards Brian Head Resort Nippon Cable Stevens Pass Bromley Nordic Mountain Sugarloaf Bryce Resort Northstar California Suicide Six Ski Area Camelback Resort Okemo Mountain Resort Summit at Snowqualmie Camp Fortune Omni Mountain Washington Resort Sun Peaks Resort Canyons Panorama Mountain Resort Sun Valley Resort Cascade Mountain Park City Mountain Resort Sunday River Catamount Pats Peak Sunrise Park Resort Chinese ski inustry Pebble Creek Tamarack Resort CNL Financial Peek’n Peak Resort Telluride Cooper Mountain Pico Mountain Texas Capital Partners Cranmore Mountain Resort Powderhorn Resort Timber Ridge Ski Area -

WIR Englisch 14 01 15 7.Indd

February 2014 No. 192 • 39th Year Aerial tram with seat heating: world first on the 150-ATW Piz Val Gronda in Ischgl, Tyrol. The design and functionality of this installation also include special features such as the cabin layout with seats along the wall and in the center. p.6 10-MGD boosts uphill performance for La Tovière 35 Doppelmayr lifts for the Winter French ski region Tignes/Espace Killy. p.8 Olympics in Sochi/Krasnaya Polyana. More staying guests thanks to new tramway pp.2-5 Tourism gets a boost in Blatten, Central Switzerland. p.10 New lifts for the Allgäu Alps Combined ticketing thanks to the latest installations. pp.12-15 Six-Packs for Vail and Whistler A major step toward further development of the ski resorts. pp.16-19 Caracas: New ropeway for public transport network Cabletren Bolivariano links district of Petare with the Metro. p. 20 Expansion of Doppelmayr After-Sales All systems go at Doppelmayr Russia. p.22 2 Doppelmayr/Garaventa Group 35 Doppelmayr lifts for the Winter Olympics Doppelmayr has supplied 35 he Winter Olympics were awarded The stadiums for indoor events are at lifts that are operating in the to Russia in 2007, triggering a huge the site on the coast, while Krasnaya Poly- Teconomic boom for the entire region. ana will host the skiing competitions. These Olympic region of Krasnaya While Doppelmayr had already built two sports centers are linked by a modern Polyana in Russia's Caucasus ropeway installations here prior to that date, highway as well as a brand new rail line. -

Keystone Resort Dercum Mountain Improvements Project Environmental Assessment I Table of Contents

DERCUM MOUNTAIN IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FEBRUARY 2014 USDA Forest Service White River National Forest Dillon Ranger District The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE AND NEED ................................................................................................................................. 1-1 A. Document Structure ..................................................................................................................................... 1-1 B. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ -

8128 Summer Play Guilde 2019 R10.Indd

Looking for a digital copy? Want to know what’s happening around the resort? Head over to KeystonePlayGuide.com! playguidesummer 2019 DISCOVER ALL THE WAYS TO PLAY ON AND OFF THE MOUNTAIN 1 summer events June September Keystone Bacon & Bourbon Festival Taste of Keystone June 22 - 23 September 1 Kick-off our summer festival season with bacon, bacon and more bacon! Round out your Labor Day Weekend with the annual Taste of Keystone. Join us for a weekend of delicious bacon-inspired cuisine, whiskey tastings Enjoy sampling dishes from the resort's award-winning culinary talent while and great live music from the Village stage. strolling around the shores of Keystone Lake. Kids’ activities and live music keep the day fun for the whole family! Kidtopia Stars & Guitars July 4 - 7 Enjoy four days of family fun with Keystone's Star & Guitars celebration. Recurring Events Pack you dancing shoes for live music from the Village stage, cruise around Friday Afternoon Club during the bike parade, feast on BBQ, cupcakes and plenty s'more! It's a Fridays, June 14 - August 30 giant birthday party for America--and you! Kick off your weekend in style with an afternoon of live music, delicious food and drinks, and mountaintop activities including horseshoes, corn hole and July ladder ball! Keystone Wine & Jazz Festival FREE gondola/lift foot passenger tickets are available at the River Run July 13 – 14 Ticket Office every Friday, 1 - 7 p.m. Free live music begins at 4 p.m. weekly. Join us in scenic River Run Village for two days of wine tasting, great food and live jazz. -

Trail, Or Are Not Visible from Above

AA BB CC DD EE FF GG HH II JJ KK LL MM paper. recycled on Printed Heads Up—Know the Code, It’s Your Responsibility reserved. rights All Inc. Trademarks, Vail Designated trademarks are the property of of property the are trademarks Designated Vail Resorts Management Company. Company. Management Resorts Vail © You are on one of the great ski mountains of the world. But you aren’t alone. There 2008 1 are many other skiers and riders here to relish the experience too. Please, respect K_\9XZb9fncj each other’s space, act responsibly, and watch your relative speed. Check the daily grooming report for monitored runs, and don’t hesitate to talk to The fastest way to Two Elk our staff in the red and yellow jackets. The mountain is waiting. restaurant is to ski down Whisky Jack and ride Your Responsibility Code Vail Mountain is committed to promoting skier safety. Sourdough Express (Chair #14) In addition to people using traditional alpine ski equipment, you may be joined on the slopes by snowboarders, telemark skiers or cross-country skiers, skiers with disabilities, skiers with specialized equipment and others. Always show courtesy to 2 others and be aware that there are elements of risk in skiing and snowboarding that common sense and personal awareness can help reduce. Know your ability level and stay within it. Observe “Your Responsibility Code” listed below and share with other skiers the responsibility for a great skiing experience. 1. always stay in control, and be able to stop or avoid other people or objects. 2. -

NSAA Ski Lift Safety Fact Sheet

CONTACT: Adrienne Saia Isaac Director of Marketing & Communications [email protected] (720) 963-4217 office UPDATED: December 2018 NSAA Ski Lift Safety Fact Sheet In the 2017/18 season, ski lifts and aerial tramways transported a total of 53.3 million skiers a total of 200 million miles. The last guest fatality resulting from a mechanical malfunction of a ski lift occurred in the 2016/17 season. Since 2004, there have been three fatalities resulting from falls from chairlifts unrelated to mechanical malfunctions. A passenger is five times more likely to suffer a fatality riding an elevator than a ski lift, and more than eight times more likely to suffer a fatality riding in a car than on a ski lift. Lift maintenance, safety and operation is governed by ANSI B77 and regulated in many states by a state agency. Overview Aerial ropeways (including lifts, trams, and gondolas) remain one of the safest methods of transportation. Ski areas across the United States are committed to lift safety and have an excellent safety record for uphill transportation as a result of this commitment. There is no other transportation system that is as safely operated, with so few injuries and fatalities, as the uphill transportation provided by chairlifts at ski resorts in the United States. Methodology & Terms NSAA compiles lift incident information and updates this Ski Lift Safety Fact Sheet annually to provide ski areas and the public with the most current information on the ski industry’s commitment to overall lift safety, financial investment in lifts and lift maintenance, industry education and training on lifts, and frequently asked questions about chairlifts. -

The Winter Blues Travel Savings Tips

WINTER 2020 LIFE INSURANCE AND LONG-TERM CARE: IT’S ABOUT FAMILY HIT THE SLOPES AT THESE FAMILY-FRIENDLY SKI RESORTS WAYS TO BEAT 9 THE WINTER BLUES SIMPLE & SMART TRAVEL SAVINGS TIPS A LETTER FROM OUR OFFICE DEAR CLIENT, It’s hard to believe that 2019 has already come and gone. What a great year it was, and we’re so honored we were able to serve you and your family. And now that 2020 is underway, we hope you had a joyous holiday season and a great winter thus far! Winter, along with a new year, reminds us of many things to be grateful for like family, new beginnings, and a slower pace of life. For our first seasonal newsletter article in 2020, we wanted to focus on you and your family. Our leading article highlights the importance of long-term care (LTC) insurance and life insurance for you and your family, along with reasons one may consider a policy. In our second article, we hit the slopes to find some of the best family-friendly ski resorts in America. We combined personal knowledge with hours of research to highlight four great options to consider on each coast for your next mountain trip. Then, with winter well underway, it’s no secret the conditions outside can put a damper on our lives. The wayward weather can even cause clinical depression. With that in mind, we defined nine tried and true ways that you can battle back to beat those pesky winter blues. Lastly, if you're experiencing cabin fever or just want to get away, it's a perfect time of year to begin preparations for your next grand vacation. -

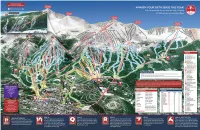

LEGEND Keystone Totals

GRAYS PEAK 14,270 MOUNT EDWARDS 13,850 ARGENTINE PEAK 13,738 GLACIER MOUNTAIN 12,443 MOUNT GUYOT 13,370 WAPITI PEAK 12,354 KEYSTONE PEAK 1.25 miles The Outback™ 11,980' 12,408 ALL UPPER BOWL ACCESS NORTH BOWL G SOUTH BOWL FROM OUTPOST LODGE o Closes at 1:30 p.m. a Closes at 1:30 p.m. l p o Outer 1 mile C s ERICKSON BOWL h t Limits m P ri G adiu um st u St a Closes at 1:30 p.m. m l e Bo INDEPENDENCE MOUNTAIN a l Th es w s y hut l C Wombat S T y Chutes 12,614 tra re tor Bingo y e ic Tele H T V Trees Tom or h est my se e qu Forest Service Access Kn C on 1.75 miles .5 miles ock or C p er ra ra l e T Th Den The Black Forest INDEPENDENCE BOWL BERGMAN BOWL olf W M Closes at 1:30 p.m. Closes at 1:30 p.m. Rath he r B bone T W . T la f o oa c ol lv d k w er ’ n r s O . e in R o b e W B r Co o p . orn m r W i I uco i e l c en P pi T k il d k n a c ld y 8 ha fi R rt 6 w re id e 1 h e s ib us I e P n e L A B ik r l 1.5 miles r a d h e b T T a g o w y t m d B P E E y o E o o F t ri br ad z , l l r t r B z h l rc k k I a a a i k f e P r O u c b p R R B i G R e i y n u u L e u Se e n n ea de NORTHNORTH PEAK h n a i T R The Outpost 11,660 B t i gh g ni THE WINDOWS R h id ou o M le Trot r Closes at 2:00 p.m. -

NEPA Analysis

Notice of Proposed Action Keystone Resort Dercum Mountain Improvements Project Dillon Ranger District, White River National Forest Summit County, Colorado Comments Welcome The Dillon Ranger District of the White River National Forest (WRNF) welcomes your comments on proposed projects on Dercum Mountain at Keystone Ski Resort. Your comments will help us complete an environmental assessment (EA). Details on how to comment are found at the conclusion of this document. Consistent with direction found in 36 CFR §215.5 (Legal Notice of Proposed Actions) this Notice of Proposed Action (NOPA) has been prepared to solicit public comments on: the Purpose and Need for Action; the Proposed Action; and potential alternatives to the Proposed Action. Potential effects of the Proposed Action on the human and biological environment will be analyzed and disclosed in an EA, which will take into account public comment received in response to this NOPA. A Decision Notice will be released concurrent with the EA. A Decision Notice will document the Responsible Official’s selected alternative. Per 36 CFR §215 (Notice, Comment, and Appeal Procedures for National Forest System Projects and Activities) a 45-day administrative appeal period will accompany release of the Decision Notice. Background Keystone Ski Resort (Keystone) opened to the public in 1970. Keystone operates under a Forest Service-issued special use permit (SUP) authorizing the use of National Forest System (NFS) lands for the purposes of constructing, operating, and maintaining a winter sports resort, including food services, rentals, retail sales, and other ancillary facilities. The SUP covers 8,536 acres on the Dillon Ranger District of the WRNF approximately six miles south on Highway 6 from the Silverthorne/Dillon exit off Interstate 70. -

Vail Resorts Annual Report 2020

Vail Resorts Annual Report 2020 Form 10-K (NYSE:MTN) Published: September 24th, 2020 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended July 31, 2020 or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-09614 Vail Resorts, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 51-0291762 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 390 Interlocken Crescent Broomfield, Colorado 80021 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (303) 404-1800 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.01 par value MTN New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. ☒ Yes ☐ No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. ☐ Yes ☒ No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports) and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.