Music As Literature, Literature As Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YCH Monograph TOTAL 140527 Ts

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1hr7f5x4 Author Hu, Yuchun Chloé Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 Copyright by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary by Yu-Chun Hu Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair Music and vision are undoubtedly connected to each other despite opera and film. In opera, music is the primary element, supported by the set and costumes. The set and costumes provide a visual interpretation of the music. In film, music and sound play a supporting role. Music and sound create an ambiance in films that aid in telling the story. I consider the musical to be an equal and reciprocal balance of music and vision. More importantly, a successful musical is defined by its plot, music, and visual elements, and how well they are integrated. Observing the transformation of the musical and analyzing many different genres of concert music, I realize that each new concept of transformation always blends traditional and contemporary elements, no matter how advanced the concept is or was at the time. Through my analysis of three musicals, I shed more light on where this ii transformation may be heading and what tradition may be replaced by a new concept, and vice versa. -

Assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Morgan Robertson & Ellie Wise Junior Voice Recital assisted by Katie Rowan, Accompanist Tuesday, April 9, 2013 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM I Wish It So from Juno Marc Blitzstein • 1905 - 1964 My Ship from Lady in the Dark Kurt Weill • 1900 - 1950 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Out There from Hunchback of Notre Dame Stephen Schwarts • b. 1948 Alan Menken • b. 1949 There Won’t Be Trumpets from Anyone Can Whistle Stephen Sondhiem • b. 1930 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Take Me to the World from Evening Primrose Stephen Sondheim The Girls of Summer from Marry Me a Little Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim My New Philosophy from You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown Clark Gesner • 1938 - 2002 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Mr. Snow from Carousel Richard Rodgers • 1902 - 1979 Oscar Hammerstein II • 1895 - 1960 Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist My Party Dress from Henry and Mudge Kait Kerrigan • b. 1981 Brian Loudermilk • b. 1983 Ellie Wise, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist INTERMISSION Always a Bridesmaid from I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change Jimmy Roberts Morgan Robertson, Soprano; Katie Rowan, Accompanist Music and the Mirror from A Chorus Line Joe DiPietro • b. -

Scenes from Opera and Musical Theatre

LEON WILSON CLARK OPERA SERIES SHEPHERD SCHOOL OPERA presents an evening of SCENES FROM OPERA AND MUSICAL THEATRE Debra Dickinson, stage director Thomas Jaber, musical director and pianist January 30 and 31, February 1 and 2, 1998 7:30 p.m. Wortham Opera Theatre RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM DER FREISCHOTZ Music by Carl Maria von Weber; libretto by Johann Friedrich Act II, scene 1: Schelm, halt' fest// Kommt ein schlanker Bursch gegangen. Agatha: Leslie Heal Annie: Laura D 'Angelo CANDIDE Music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by John Latouche, Dorothy Parker, Stephen Sondheim, Richard Wilbur OHappyWe Candide: Matthew Pittman Cunegonde: Sibel Demirmen \. THE THREEPENNY OPERA Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Bertolt Brecht The Jealousy Duet Lucy Brown: Aidan Soder Polly Peachum: Kristina Driskill MacHeath: Adam Feriend DON GIOVANNI Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte Act I, scene 3: Laci darem la mano/Ah! fuggi ii traditor! Don Giovanni: Christopher Holloway Zerlina: Elizabeth Holloway Donna Elvira: Michelle Herbert STREET SCENE Music by Kurt Weill; lyrics by Elmer Rice Act/I Duet Rose: Adrienne Starr Sam: Matthew Pittman MY FAIR LADY Music by Frederick Loewe; lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner On the Street Where You Live/Show Me Freddy Eynsford Hill: David Ray Eliza Doolittle: Dawn Bennett LA BOHEME Music by Giacomo Puccini; libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica Act/II Mimi: Kristin Nelson Marcello: Matthew George Rodolfo: Creighton Rumph Musetta: Adrienne Starr Directed by Elizabeth Holloway INTERMISSION LE NOZZE DI FIGARO -

Street Scene

U of T Opera presents Kurt Weill’s Street Scene Artwork: Fred Perruzza November 22, 23 & 24, 2018 at 7:30 pm November 25, 2018 at 2:30 pm MacMillan Theatre, 80 Queen’s Park Made possible in part by a generous gift from Marina Yoshida. This performance is funded in part by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land. Street Scene Based on Street Scene by Elmer Rice Music by Kurt Weill Lyrics by Langston Hughes Conductor: Sandra Horst Director: Michael Patrick Albano Set and Lighting Design: Fred Perruzza Costume Design: Lisa Magill Choreography: Anna Theodosakis* Stage Manager: Susan Monis Brett* +Peter McGillivray’s performance is made possible by the estate of Morton Greenberg. *By permission of Canadian Actors’ Equity Association The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc. promotes and perpetuates the legacies of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya by encouraging an appreciation of Weill’s music through support of performances, recordings, and scholarship, and by fostering an understanding of Weill’s and Lenya’s lives and work within diverse cultural contexts. It administers the Weill-Lenya Research Center, a Grant and Collaborative Performance Initiative Program, the Lotte Lenya Competition, the Kurt Weill/Julius Rudel Conducting Fellowship, the Kurt Weill Prize for scholarship in music theater; sponsors and media. -

The 13 Best Broadway Songs About Getting Older | Next Avenue

The 13 Best Broadway Songs About Getting Older | Next Avenue http://www.nextavenue.org/blog/13-best-broadway-songs-about... View Edit Revisions Workflow From our sponsors : The 13 Best Broadway Songs About Getting Older Tony-nominated Andrea Martin steals 'Pippin' with her trapeze-swinging rendition of 'No Time At All.' Here are more boomer-friendly show tunes. posted by John Stark, June 7, 2013 More by this author John Stark is the articles editor of Next Avenue. Follow John on Twitter @jrstark. New York theatergoers can’t stop talking about Andrea Martin’s Tony-nominated performance in the current revival of the Broadway musical Pippin. (You can find out if she wins Best Performance by an Actress in a Featured Role in a Musical on the Annual Tony Awards this Sunday, 8 p.m. Eastern time, CBS). The highlight of this circus-inspired Pippin is Martin’s rendition of “No Time At All,” a feel-good motivational song about living every moment of your life before The company of "Pippin." it’s too late. The new cast album Photo by Joan Marcus, courtesy TonyAwards.com was released this week. Martin, known for stealing scenes (who can forget her as Aunt Voula in “My Big Fat Greek Wedding”?) has redefined the role of Charlemagne’s mother, Berthe, Pippin's grandmother. She doesn’t play her sitting in a wheelchair or using a cane. Martin executes derring-do circus acts, like swinging from a trapeze. “I am the age the character is singing about,” Martin recently told The Wall Street Journal, “and in the 40 years since the show first ran, 66 has changed.” Martin’s performance got me to thinking about other show tunes that are sung by mature characters (though not from a trapeze). -

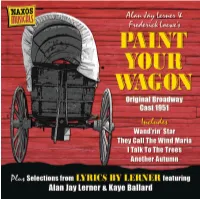

Paint Your Wagon Original Broadway Cast 1951 Rewrites Could Fix the Problems of the Script Still See Elisa) Beautifully

120877bk Paint Your Wagon:MASTER 3+3 16/7/08 10:48 AM Page 2 Paint Your Wagon 9. Whoop-Ti-Ay! 1:45 Lyrics By Lerner 22. Progress 4:07 Chorus Alan Jay Lerner and Quartet Original Broadway Cast 1951 16. Wand’rin’ Star 3:00 10. Carino Mio 2:46 23. Susan’s Dream 5:53 1. I'm On My Way 3:53 Alan Jay Lerner and Quartet Olga San Juan, Tony Bavaar Kaye Ballard and Quartet Rufus Smith, Robert Penn, Dave Thomas 17. I Talk To The Trees 2:33 and Chorus 11. There’s A Coach Comin’ In 1:59 Alan Jay Lerner 24. Mr Right 3:37 Chorus Kaye Ballard 2. Rumson 0:47 From Paint Your Wagon Robert Penn 12. Hand Me Down That Can O’ Beans Music by Frederick Loewe From Love Life 1:45 Music by Kurt Weill 3. What’s Goin’ On Here 3:27 Robert Penn and Chorus 18. Green-Up Time 2:12 Olga San Juan Kaye Ballard Tracks 16–24: Heritage H 0060 13. Another Autumn 2:53 Billy Taylor, piano; Allen Hanlon, guitar; 4. I Talk To The Trees 3:32 19. Love Song 3:11 Tony Bavaar, Rufus Smith Milt Hinton or Clyde Lombardi, bass; Tony Bavaar Alan Jay Lerner 14. All For Him 2:29 Herb Harris or Percy Brice, drums 5. They Call The Wind Maria 3:17 Olga San Juan 20. Economics 3:22 Recorded 1955 Rufus Smith and Chorus Quartet 15. Wand’rin’ Star 2:31 6. I Still See Elisa 3:18 James Barton and Chorus 21. -

Street Scene

Kurt Weill’s Street Scene A Study Guide prepared by VIRGINIA OPERA 1 Please join us in thanking the generous sponsors of the Education and Outreach Activities of Virginia Opera: Alexandria Commission for the Arts ARTSFAIRFAX Chesapeake Fine Arts Commission Chesterfield County City of Norfolk CultureWorks Franklin-Southampton Charities Fredericksburg Festival for the Performing Arts Herndon Foundation Henrico Education Fund National Endowment for the Arts Newport News Arts Commission Northern Piedmont Community Foundation Portsmouth Museum and Fine Arts Commission R.E.B. Foundation Richard S. Reynolds Foundation Suffolk Fine Arts Commission Virginia Beach Arts & Humanities Commission Virginia Commission for the Arts Wells Fargo Foundation Williamsburg Area Arts Commission York County Arts Commission Virginia Opera extends sincere thanks to the Woodlands Retirement Community (Fairfax, VA) as the inaugural donor to Virginia Opera’s newest funding initiative, Adopt-A-School, by which corporate, foundation, group and individual donors can help share the magic and beauty of live opera with underserved children. For more information, contact Cecelia Schieve at [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of World Premiere 3 Cast of Characters 3 Musical numbers 4 Brief plot summary 5 Full plot synopsis with musical examples 5 Historical background 12 The creation of the opera 13 Relevance of social themes in 21st century America 15 Notable features of musical style 16 Discussion questions 19 3 STREET SCENE AN AMERICAN OPERA Music by KURT WEILL Book by ELMER RICE, adapted from his play of the same name Lyrics by LANGSTON HUGHES Premiere First performance on January 9, 1947 at the Adelphi Theater in New York City Setting The action takes place outside a tenement house in New York City on an evening in June 1946. -

LOVE LIFE Your Personal Guide to the Production

NEW YORK CITY CENTER EDUCATION MARCH 2020 BEHIND THE CURTAIN: Wiseman Art by Ben ENCORES! LOVE LIFE Your personal guide to the production. TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTEXT 2 A Note from Jack Viertel, Encores! Artistic Director 3 Meet the Creative Team 4 Meet the Cast 5 An Interview with Costume Designer Tracy Christensen 7 Love Life in the 21st Century by Rob Berman and Victoria Clark RESOURCES & ACTIVITIES 10 Before the Show 11 Intermission Activity 13 After the Show 14 Glossary 15 Up Next for City Center Education CONTEXT Selecting shows for Encores! has always been a wonderfully A NOTE FROM enjoyable but informal process, in which Rob Berman, our Music Director and I toss around ideas and titles until we feel like we’ve achieved as perfect a mix as possible: three shows that we are as eager to see as we are to produce, and three JACK that are nothing alike. This year was different only in that we were joined by Lear deBessonet, who will begin her tenure as my successor next season. That only made it more fun, and VIERTEL, we proceeded as if it were any other season. ENCORES! Although we never considered the season a “themed” one— it turned out to have a theme: worlds in transition. And I ARTISTIC suppose my world, and maybe the world of Encores! itself are DIRECTOR about to change too—so it seems appropriate. Love Life is a case in point. Produced in 1948, it is Alan Jay Lerner and Kurt Weill’s only collaboration (they had tremendous success in other collaborations, including My Fair Lady and The Threepenny Opera). -

Musical Theatre S & E

Musical Theatre Solo & Ensemble Festival Solos & Duets only this year Festival is November 12 , 2011 at Parker Middle School in Howell Guidelines and Rules -To be eligible for a rating each participating entry is required to sing two selections of contrasting character one song must be from before 1965.. -Adjudicators MUST be provided with original copies of each selection with all measures clearly numbered or a rating will not be issued. -Use of illegally duplicated copies will disqualify the soloist or ensemble from receiving a rating. However, the event will be allowed to perform for comments only. -When performing music requiring accompaniment, live accompaniment must be used. -Registrants will be allotted a minimum of 15 minutes which includes entry and exit from room -We will be using the new S&E rubric for this event Additional Requirements for Soloists -$22 per event -Please choose two selections: an up-tempo and a ballad. Contrasting Styles, one song must be before 1965 Here is a list of recommended composers to choose from: Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Hoagy Carmichael, Vernon Duke, Duke Ellington, George and Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Hart and Loewe, Arthur Schwartz, Jule Styne, Jimmy Van Heusen, Vincent Youmans, early Stephen Sondheim, early Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Weill. -Soloists MUST perform from memory Additional Requirements for Duets - $38 per event - Please choose two selections: an up-tempo and a ballad. Contrasting Styles, one song must be before 1965. Here is a list of recommended composers to choose from: Harold Arlen, Irving Berlin, Hoagy Carmichael, Vernon Duke, Duke Ellington, George and Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Rodgers and Hart, Rodgers and Hammerstein, Hart and Loewe, Arthur Schwartz, Jule Styne, Jimmy Van Heusen, Vincent Youmans, early Stephen Sondheim, early Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Weill. -

A Performer's Guide to the American Theater Songs of Kurt Weill

A Performer's Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Morales, Robin Lee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 16:09:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194115 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO THE AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATER SONGS OF KURT WEILL (1900-1950) by Robin Lee Morales ________________________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 8 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As member of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read document prepared by Robin Lee Morales entitled A Performer’s Guide to the American Musical Theater Songs of Kurt Weill (1900-1950) and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Faye L. Robinson_________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Edmund V. Grayson Hirst__________________ Date: May 5, 2008 John T. Brobeck _________________________ Date: May 5, 2008 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

New York City Center Announces Upcoming Encores! Productions

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: New York City Center announces upcoming Encores! productions: The Life, Adapted and Directed by Tony Award winner Billy Porter; The Tap Dance Kid, Directed by Tony Award winner Kenny Leon, Adapted by Lydia Diamond; and An Annual Celebration of Iconic American Musicals: a new tradition at City Center exploring the ways musical theater connects us across generations In-development productions and spring 2020 cancelled shows explored in new behind-the-scenes digital series Encores! Inside the Revival launching October 14 Encores! team adds new leadership and artistic voices: Tony Award winner Clint Ramos joins as Encores! Producing Creative Director Camille A. Brown, Eisa Davis, and Robert O’Hara join as Encores! Creative Advisors Jenny Gersten to serve as Producer of Musical Theater for New York City Center New York, NY/September 18, 2020 – New York City Center President & CEO Arlene Shuler today announced the musical productions in development as part of the next chapter of the longstanding Tony-honored Encores! series, all of which will be explored in-depth as part of the 2020-2021 season in a new digital series Encores! Inside the Revival. The five-part mini documentary series, which launches Lear deBessonet’s first season as Encores! Artistic Director, will explore the behind-the-scenes process—through conversations and performances—for the productions being developed and ultimately produced at City Center upon reopening. “Last fall, when I began to program my first Encores! season I never could have imagined the world in which we find ourselves today. As we look ahead, it is essential that we preserve the Encores! mission and weave an ever- deepening portrait of the history of American musicals. -

AQA Music a Level Area of Study 4: Music for Theatre

AQA Music A Level Area of Study 4: Music for Theatre NAME: TEACHER: 1 Contents Page Contents Page number What we are studying 3 Timeline 4 Kurt Weill 5 The Threepenny Opera 6 Rise and Fall of Mahagonny 9 Richard Rodgers 10 Oklahoma! 11 Carousel 15 Stephen Sondheim 16 Sweeney Todd 17 Into The Woods 21 Claude-Michel Schonberg 22 Miss Saigon 23 Les Miserables 26 Jason Robert Brown 27 The Last Five Years 28 Parade 31 Essay Questions and unfamiliar listening tests 32 Vocabulary specific to this unit 33 2 One essay question will be set on this topic. You will choose between answering an essay on Music for Theatre or on Jazz. You will need to answer listening questions and shorter essay questions on both topics, so you must study both. You will be studying these named artists and these suggested pieces from the board: Artists Pieces (Suggested listening) Kurt Weill Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny: - ‘Alabama Song’ - ‘Havana Song’ The Threepenny Opera: - ‘Ballad of Mack the Knife’ - ‘Jealousy Duet’ - ‘Pirate Jenny’ Richard Rogers Oklahoma!: - ‘Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’’ - ‘Lonely Room’ - ‘Oklahoma’ Carousel: - ‘Louise’s Ballet: Pas de deux’ - ‘What’s the Use of Wond’rin?’ Stephen Sondheim Sweeney Todd: - ‘Prelude’ - ‘Green Finch and Linnet Bird’ - ‘A Little Priest’ - ‘My Friends’ Into The Woods: - ‘On the Steps of the Palace’ - ‘Agony’ - ‘Giants in the Sky’ - ‘Last Midnight’ Claude-Michel Miss Saigon: Schönberg - ‘I’d Give My Life for You’ - ‘Bui Doi’ - ‘I Still Believe’ Les Miserables: - ‘One Day More’ - ‘Bring Him Home’ Jason