SC13-425 Larry Eugene Mann Vs. State of Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHERIFFS STAR VOL 36, NO 1, FEB-MAR 1992.Pdf

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ II ~ I ~ I ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ I ~ Reapportioning Florida By Maury Kalchakian General Counsel Florida Sheriffs Association After each decennial (ev- ery ten years) census, Florida CONTENTS is required to reapportion its state legislative and U.S.Con- gressional districts. The legis- MauryMau KolchaKolchakian lature is currently in the throes of this procedure, and, Florida SherdS Association Page practically speaking, the job must be completed prior to the (Micers. ...........,...........,.........................................2 1992 general elections. Board ofDirectors .......................... .... Reapportionment is the process of re-dividing a given . .. ..............3 number ofseats (40 in the State Senate, 120in the House) FLORIDA'S GOVKKGKNT among units ofgovernment or geographic districts. This is Stttte Government Chart ...................,..........,......4 usually done according to an established plan or formula. Executive Branch ......„,........ ,......... .,...... .-. ... 6 The number of state legislative districts will not in- . .. .. .. crease. However, some areas ofthe state are growing faster Directory of State Agencies ...„......,...........,.......11 than others, and therefore the district boundary lines will Legislative Branch ...„...........,...........,..........,....14 have to be changed to give all Florida residents equal Judicial Branch ..........,..........„.....,.....................21 representation. Florida's The 1990 census gave Florida a population of 12.94 U,S. Senators million, a hefty increase -

Adapting Crisis Change

SPRING / SUMMER 2021 A Publication of THE FLORIDA SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY ADAPTING AMID CRISIS AND CHANGE AN INTERVIEW WITH WELCOMING HISTORICAL SOCIETY JUSTICE HATCHETT JUSTICE COURIEL JUSTICE HOSTS VIRTUAL HONORED AND PAGE 10 GROSSHANS ANNUAL EVENT REMEMBERED PAGE 14 PAGE 23 PAGE 26 Contents 6 19 31 37 MESSAGE FROM FLORIDA HISTORICAL FLORIDA THE CHIEF JUSTICE LEGAL HISTORY SOCIETY NEWS LEGAL HISTORY The Pandemic All Eyes Turn Remembering Stare Decisis and Beyond to Judge Chief Justice in Florida Chief Justice Barbara Lagoa Gerald Kogan: During the Charles T. Canady Craig Waters A Legal Legend Civil War Who Opened The Honorable 8 21 Florida’s Robert W. Lee FLORIDA SUPREME FLORIDA SUPREME Courts to COURT NEWS COURT NEWS the People Justices Luck 40 Long-Time Craig Waters FLORIDA and Lagoa Florida LEGAL HISTORY Appointed to Supreme Court The Florida the U.S. Court Librarian, 34 Judicial HISTORICAL of Appeals for Billie J. Blaine, SOCIETY NEWS Qualifications the Eleventh Retires Justice James Commission: Circuit Erik Robinson E. Alderman: Its Purpose, Samantha Lowe 1936-2021 Powers, Craig Waters Processes, 23 and Public 10 HISTORICAL FLORIDA SUPREME SOCIETY EVENTS Responsibility COURT NEWS A Supreme 36 Dr. Steven R. Maxwell HISTORICAL An Interview Evening: 2021 SOCIETY NEWS with Florida in the Virtual Remembering Supreme Court World Historical Justice John Hala Sandridge Society D. Couriel Trustee Joseph Raul Alvarez R. Boyd 26 James M. Durant, Jr. HISTORICAL 14 SOCIETY NEWS FLORIDA SUPREME Former Justice COURT NEWS Joseph W. Meet the Hatchett Newest Honored Supreme Court With Society’s Justice: Jamie Lifetime R. Grosshans Achievement Renee E. -

Rosemary Barkett Outstanding Achievement Award Nomination Form DEADLINE: FEBRUARY 1, 2018

Rosemary Barkett Outstanding Achievement Award Nomination Form DEADLINE: FEBRUARY 1, 2018 Rosemary Barkett became the first female Florida Supreme Court Justice when she was appointed by Governor Bob Graham on October 14, 1985. She was inducted into the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame in 1986. In 1994, President Bill Clinton named her to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. In 2013, Justice Barkett was appointed to the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal in The Hague where she continues to serve today. This award is presented in her honor. Criteria for Selection: FAWL’s highest award is presented annually to a FAWL member who (1) has demonstrated a commitment to the mission and goals of FAWL; (2) has excelled to outstanding career achievement that charters new territory in our profession; (3) has helped to overcome traditional stereotypes associated with women by breaking barriers, molding a new reality and a new way of thinking about themselves, others and their place in the universe or has promoted the status of women within the profession; (4) has advanced the status of women in the State of Florida; (5) is an active member of FAWL (membership dues are paid for the 2017-2018 year); and (6) is in good standing with the Florida Bar. Membership in the Mattie Belle Davis Society will also be considered. For a list of the previous winners of the Rosemary Barkett Outstanding Achievement Award, please see the second page of this nomination form. Chapter Nomination Eligibility: Each chapter in good standing is eligible and encouraged to nominate an outstanding member of the legal community. -

State of the Court 2013 Report

United States District Court Southern District of Florida STATE OF THE COURT REPORT 2013 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Wilkie D. Ferguson, Jr. Courthouse James Lawrence King Federal (Miami) Justice Building (Miami) C. Clyde Atkins Courthouse Sidney M. Aronovitz Courthouse (Miami) (Key West) Alto Lee Adams, Sr. Courthouse U. S. Federal Building and (Fort Pierce) Courthouse (Fort Lauderdale) Paul G. Rogers Federal Building and Courthouse (West Palm Beach) TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Message from the Court Administrator 5-6 The Southern District of Florida: A Rich History 7-9 The Judges of the District—District Judges 10-11 The Judges of the District—Magistrate Judges 12—22 Statistical Charts and Graphs of Court Operations 23—26 Special Events and Occasions 27—29 2013 Priority Projects and Accomplishments THIS REPORT WAS PREPARED BY THE OFFICE OF THE COURT ADMINISTRATOR • CLERK OF COURT UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA WILKIE D. FERGUSON, JR. UNITED STATES COURTHOUSE 400 NORTH MIAMI AVENUE, ROOM 8N09 MIAMI, FL 33128-7716 PHONE: (305) 523-5100 WWW.FLSD.USCOURTS.GOV MESSAGE FROM THE COURT ADMINISTRATOR “2013—A Banner Year” his was a banner year in the Southern District of Florida, with many firsts and high rankings. T Once again, our Court ranked first in the nation in total trials among the 94 District Courts, and first in jury trials. Our Court ranked second nationally in productivity rankings. The Clerk’s Office was equally effective in various areas, such as ranking first among large Courts in the Jury Utilization Index. hese numbers only tell part of the story. -

For Immediate Release Contact: Scherley Busch, 305-661-6605, [email protected]

For Immediate Release Contact: Scherley Busch, 305-661-6605, [email protected] HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHIC EXHIBIT HONORS WOMEN FLORIDA WOMEN OF ACHIEVEMENT CELEBRATES ITS 2OTH ANNIVERSARY DEBUTING NEWEST PORTRAITS BY PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTIST SCHERLEY BUSCH Over 100 guests, including community leaders and students, were on hand for an exhibition reception and awards ceremony in honor of the newest members of FWA’s impressive roster of women leaders as Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos A. Gimenez joined the celebration to present a proclamation in celebration of the Florida Women of Achievement at Barry University’s Andy Gato Gallery in Miami Shores, 11300 N.E. 2nd Avenue Miami Shores, FL 33161. This year artist Scherley Busch captured photographic portraits of new inductees City of Homestead’s first woman council member, Ruth L. Campbell; Miami-Dade County Commissioner Sally Heyman; Miami Lighthouse for the Blind CEO/president Virginia Jacko; State Senator Gwen Margolis; mentor/public speaker Tracy Wilson Mourning; Good Government Initiative President/CEO Katy Sorensen; business executive and philanthropist Mary Spencer; and entrepreneur/community activist Carol Williamson. Recognized for their outstanding contributions and positive influence on our state, the women join the on going collection which was started in 1992 by Busch. Reflecting diverse cultures, ethnicities and careers, the inductees include leaders and trailblazers as Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Athalie Range, Gloria Estefan and Chris Evert. The entire collection of FWA will remain on display through April 23 at Barry University’s Gato Gallery, open daily from 8 a.m.-10 p.m. “What began as the women's movement in the 70s has evolved into a phenomenal consciousness of the importance of giving women opportunities in education and career choices,” says Sister Jeanne O’Laughlin, Honorary Chair of Florida Women of Achievement. -

The 2020 Induction Ceremony Program Is Available Here

FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME VIRTUAL INDUCTION CEREMONY honoring 2020 inductees Alice Scott Abbott Alma Lee Loy E. Thelma Waters Virtual INDUCTION 2020 CEREMONY ORDER OF THE PROGRAM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women CONGRATULATORY REMARKS Jeanette Núñez . Florida Lieutenant Governor Ashley Moody . Florida Attorney General Jimmy Patronis . Florida Chief Financial Officer Nikki Fried . Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Charles T. Canady . Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice ABOUT WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME & KIOSK Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee 2020 FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME INDUCTIONS Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee HONORING: Alice Scott Abbott . Accepted by Kim Medley Alma Lee Loy . Accepted by Robyn Guy E. Thelma Waters . Accepted by E. Thelma Waters CLOSING REMARKS Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women 2020 Commissioners Maruchi Azorin, M.B.A., Tampa Rita M. Barreto, Palm Beach Gardens Melanie Parrish Bonanno, Dover Madelyn E. Butler, M.D., Tampa Jennifer Houghton Canady, Lakeland Anne Corcoran, Tampa Lori Day, St. Johns Denise Dell-Powell, Orlando Sophia Eccleston, Wellington Candace D. Falsetto, Coral Gables Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, Ft. Myers Senator Gayle Harrell, Stuart Karin Hoffman, Lighthouse Point Carol Schubert Kuntz, Winter Park Wenda Lewis, Gainesville Roxey Nelson, St. Petersburg Rosie Paulsen, Tampa Cara C. Perry, Palm City Rep. Jenna Persons, Ft. Myers Rachel Saunders Plakon, Lake Mary Marilyn Stout, Cape Coral Lady Dhyana Ziegler, DCJ, Ph.D., Tallahassee Commission Staff Kelly S. Sciba, APR, Executive Director Rebecca Lynn, Public Information and Events Coordinator Kimberly S. -

In the Company of Women Award Recipients

In the Company of Women Award Recipients Year Award Name 2010 Arts & Entertainment Nicole Henry Business & Economics Jennifer Behar Comm. & Literature C.L. Conroy Education & Research Jeanne F. Jacobs PhD Government & Law Florida State Representative Yolly Roberson Health & Human Services Adriana Cora Science and Technology Dr. Suzanne Koptur Sports & Athletics Carmen Jackson Mayor's Pioneer Award Dr. Eneida Roldan,M.D., M.P.H., M.B.A. Mayor's Pioneer Award Francis "Dolly" Macintyre Community Spirit Award Valda Clark Christain Posthumous Chief Sandrell Rivers 2009 Arts and Entertainment Ruth Wiesen Business and Economics Barbara Watson Communications and Literature Marice Cohn Band Education and Research Mercedes Toural Government and Law Commissioner Rebeca Sosa Health and Human Service Virginia A. Jacko Science and Technology Patrica Wade Sports and Athletics Jayne D. Greenberg Mayor's Pioneer Jennifer Glazer-Moon Mayor's Pioneer Mary M. Young 2008 Arts and Entertainment Barbara Stein Business and Economics Rosa Naccarota Education and Research Tonya Dillard Government and Law Maria Korvick Health and Human Service Regina Shearn Science and Technology Emilie Young Sports and Athletics Marjorie Wessel Mayor's Pioneer Elizabeth Mejia Mayor's Pioneer Elizabeth McNally 2007 Honorees Jean H. Evoy Honorees Rocio Tafur-Salgado Honorees Martha Mahoney Honorees Barbara Schwartz Honorees Teresa Maria Rojas Posthumous Linda Dakis Posthumous Peggy Shizuko Osumi Murasaki Tanaka Posthumous Dr. Margaret "Peggy" Wilson Posthumous Christine Federighi 2006 Pioneers Cindy Lerner Pioneers Roslyn Berrin Pioneers Dr. Miriam Klein Kassenoff Pioneers Paula J. Musto Honorees Elizabeth "Liz" Hernandez Honorees Leonie Marie Hermantin Honorees Judge Carroll J. Kelly Honorees Mieko Kubota Honorees Earnestine Mikki Thompson Honorees Joan Sampieri Honorees Sharon Kendrick-Johnson Honorees Susan Perry Redding Posthumous Audrey J. -

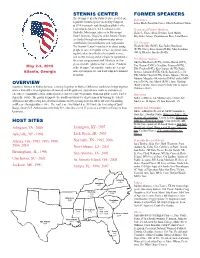

Fact Sheet 10.Indd

STENNIS CENTER FORMER SPEAKERS The Stennis Center for Public Service is a federal, First Ladies legislative branch agency created by Congress Laura Bush, Rosalynn Carter, Hillary Rodham Clinton in 1988 to promote and strengthen public service leadership in America. It is headquartered in Presidential Cabinet Members Starkville, Mississippi, adjacent to Mississippi Elaine L. Chao, Alexis Herman, Lynn Martin, State University. Programs of the Stennis Center Kay Coles James, Condoleezza Rice, Janet Reno are funded through an endowment plus private contributions from foundations and corporations. U.S. Senators The Stennis Center’s mandate is to attract young Elizabeth Dole (R-NC), Kay Bailey Hutchison people to careers in public service, to provide train- (R-TX), Nancy Kassebaum (R-KS), Mary Landrieu ing for leaders in or likely to be in public service, (D-LA), Blanche Lincoln (D-AR) and to offer training and development opportunities U.S. Representatives for senior congressional staff, Members of Con- Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Corrine Brown (D-FL), gress, and other public service leaders. Products May 2-3, 2010 Eva Clayton (D-NC), Geraldine Ferraro (D-NY), of the Stennis Center include conferences, semi- Tillie Fowler (R-FL), Kay Granger (R-TX), Eddie Atlanta, Georgia nars, special projects, and leadership development Bernice Johnson (D-TX), Sheila Jackson Lee (D- programs. TX), Marilyn Lloyd (D-TN), Denise Majette ( D-GA), Marjorie Margolies-Mezvinsky (D-PA) Cynthia McK- inney (D-GA), Sue Myrick (R-NC), Anne Northup OVERVIEW (R-KY), Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL), Karen Southern Women in Public Service: Coming Together to Make a Difference conference brings together Thurman (D-FL) women from different backgrounds—Democrats and Republicans, stay-at-home mothers and business executives, community leaders, political novices and veterans—to promote women in public service leader- Governors ship in the South. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 149 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2003 No. 135 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was Bless, we pray, all who will harvest COMMUNICATION FROM THE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- the grains of the good earth that we CLERK OF THE HOUSE pore (Mr. YOUNG of Florida). will soon enjoy on our dinner tables. Amen. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f fore the House the following commu- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER f nication from the Clerk of the House of Representatives: PRO TEMPORE THE JOURNAL The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- OFFICE OF THE CLERK, The SPEAKER pro tempore. The HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, fore the House the following commu- Chair has examined the Journal of the Washington, DC, September 26, 2003. nication from the Speaker: last day’s proceedings and announces Hon. J. DENNIS HASTERT, WASHINGTON, DC, to the House his approval thereof. Speaker, House of Representatives, September 29, 2003. Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- Washington, DC. I hereby appoint the Honorable C.W. BILL nal stands approved. DEAR MR. SPEAKER: Pursuant to the per- YOUNG to act as Speaker pro tempore on this mission granted in Clause 2(h) of Rule II of day. f the Rules of the U.S. House of Representa- J. DENNIS HASTERT, tives, the Clerk received the following mes- Speaker of the House of Representatives. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE sage from the Secretary of the Senate on f The SPEAKER pro tempore. -

In Re: State-Federal Judicial Council for Florida

IN RE: STATE-FEDERAL JUDICIAL COUNCIL FOR FLORIDA ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER The State-Federal Judicial Council for Florida was created in 1970 for the purpose of harmonizing the relationship between the state and the federal judicial systems. The Council is hereby reauthorized, and the following persons are appointed to the Council for a term to expire on June 30,2002: Re~resentatives of the Florida Su~reme Court The Honorable Charles T. Wells, Co-Chair Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Florida 500 South Duval Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1925 Mr. Thomas D. Hall Clerk, Supreme of Florida 500 South Duval Street Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1925 The Honorable Marguerite H. Davis, Executive Director Judge, First District Court of Appeal 301 Martin Luther King, Jr., Boulevard Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1850 Representatives of the U.S. Court of ADDeals for the Eleventh Circuit The Honorable R. Lanier Anderson III, Co-Chair Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit P. O. Box 977 Macon, Georgia 31202-0977 The Honorable Rosemary Barkett Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit 99 N.E. 4th Street, Suite 1262 Miami, Florida 33132 The Honorable Susan H. Black Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit P. O. Box 53135 Jacksonville, Florida 32201 The Honorable Stanley Marcus Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit 99 N.E. 4th Street, Suite 1262 Miami, Florida 33132 The Honorable Gerald Bard Tjoflat Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit P. O. BOX 960 Jacksonville, Florida 32201-0960 Ret)resentatives of the Florida District Courts of ADDeal The Honorable Jerry R. -

Immigrants, Refugees and Women: International Obligations and the United States

Emory International Law Review Volume 33 Issue 4 2019 Immigrants, Refugees and Women: International Obligations and the United States Rosemary Barkett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Rosemary Barkett, Immigrants, Refugees and Women: International Obligations and the United States, 33 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 493 (2019). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol33/iss4/1 This David J. Bederman Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BARKETTPROOFS_6.5.19 6/5/2019 10:19 AM DAVID J. BEDERMAN LECTURE IMMIGRANTS, REFUGEES AND WOMEN: INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS AND THE UNITED STATES Judge Rosemary Barkett* PROFESSOR ABDULLAHI AN-NA’IM: Hello. My name is Abdullahi An- Na’im. I teach here at Emory Law School. I am responsible for a center called Center for International and Comparative Law. It is set in the [indiscernible] place in the corner where nobody seems to go. But please, we are delighted that you are here. This is really the highlight of our annual activities. Our friend, David Bederman, in whose name and honor this lecture has been named, and there is a fellowship, too. Some of you may be aware of that. So, the next fellows are already here in the room with us. So, the idea is to present international speakers because David himself was really a master of international—private and public—law, as well as admiralty and many other things. -

2015 Rosemary Barkett Outstanding Achievement Award

2015 Rosemary Barkett Outstanding Achievement Award Rosemary Barkett became the first female Florida Supreme Court Justice when she was appointed by Governor Bob Graham on October 14, 1985. She was inducted into the Florida Women's Hall of Fame in 1986. In 1994, President Bill Clinton named her to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, where she continues to serve today. This award is presented in her honor. This award is presented annually to a FAWL member who: Demonstrated a commitment to the purpose and goals of FAWL. Excelled to outstanding career achievement that charters new territory in our profession. Helped to overcome traditional stereotypes associated with women by breaking barriers, molding a new reality and a new way of thinking about themselves, others, and their place in the universe, or has promoted the status of women with- in the profession. Advanced the status of women in the State of Florida. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. Nancy A. Daniels Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963 Nancy Daniels is the Public Defender for the Second Judicial Circuit. She has continuously won re-election to this office after making history as the first woman elected to this constitutional office in 1990. In her position, Nancy oversees six offices in the six counties of the Second Circuit and the Public Defender's office represents upwards of 14,000 clients. She has hired, promoted, worked with,· and mentored many female attorneys as Public Defender. Seven of the twelve supervisors in her office are women, and past female employees are now law firm leaders or members of the judiciary.