MCR History Talks: Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming North Staffordshire Overview

Transforming North Staffordshire Overview Prepared for the North Staffordshire Regeneration Partnership March 2008 Contents Foreword by Will Hutton, Chief Executive, The Work Foundation 3 Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 10 1.1 This report 10 1.2 Overview of North Staffordshire – diverse but inter-linked 12 1.3 Why is change so urgent? 17 1.4 Leading change 21 2. Where is North Staffordshire now? 24 2.1 The Ideopolis framework 24 2.2 North Staffordshire’s economy 25 2.3 North Staffordshire’s place and infrastructure 29 2.4 North Staffordshire’s people 35 2.5 North Staffordshire’s leadership 40 2.6 North Staffordshire’s image 45 2.7 Conclusions 48 3. Vision for the future of North Staffordshire and priorities for action 50 3.1 Creating a shared vision 50 3.2 Vision for the future of North Staffordshire 53 3.3 Translating the vision into practice 55 3.4 Ten key priorities in the short and medium term 57 A. Short-term priorities: deliver in next 12 months 59 B. Short and medium-term priorities: some tangible progress in next 12 months 67 C. Medium-term priorities 90 4. Potential scenarios for the future of North Staffordshire 101 4.1 Scenario 1: ‘Policy Off’ 101 4.2 Scenario 2: ‘All Policy’ 102 4.3 Scenario 3: ‘Priority Policy’ 104 4.4 Summary 105 5. Conclusions 106 2 Transforming North Staffordshire – Overview Foreword by Will Hutton, Chief Executive, The Work Foundation North Staffordshire is at a crossroads. Despite the significant economic, social and environmental challenges it faces, it has an opportunity in 2008 to start building on its assets and turning its economy around to become a prosperous, creative and enterprising place to live, work and study. -

Manchester Visitor Information What to See and Do in Manchester

Manchester Visitor Information What to see and do in Manchester Manchester is a city waiting to be discovered There is more to Manchester than meets the eye; it’s a city just waiting to be discovered. From superb shopping areas and exciting nightlife to a vibrant history and contrasting vistas, Manchester really has everything. It is a modern city that is Throw into the mix an dynamic, welcoming and impressive range of galleries energetic with stunning and museums (the majority architecture, fascinating of which offer free entry) and museums, award winning visitors are guaranteed to be attractions and a burgeoning stimulated and invigorated. restaurant and bar scene. Manchester has a compact Manchester is a hot-bed of and accessible city centre. cultural activity. From the All areas are within walking thriving and dominant music distance, but if you want scene which gave birth to to save energy, hop onto sons as diverse as Oasis and the Metrolink tram or jump the Halle Orchestra; to one of aboard the free Mettroshuttle the many world class festivals bus. and the rich sporting heritage. We hope you have a wonderful visit. Manchester History Manchester has a unique history and heritage from its early beginnings as the Roman Fort of ‘Mamucium’ [meaning breast-shape hill], to today’s reinvented vibrant and cosmopolitan city. Known as ‘King Cotton’ or ‘Cottonopolis’ during the 19th century, Manchester played a unique part in changing the world for future generations. The cotton and textile industry turned Manchester into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Leaders of commerce, science and technology, like John Dalton and Richard Arkwright, helped create a vibrant and thriving economy. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

DTA Newsletter Theme of the Week: School Vision

DTA Newsletter Theme of the Week: School Vision Friday 26th January Safeguarding Tip: Please take time to check the contents of your child’s school bag each week. The Mayor of Manchester Officially Opens Dean Trust Ardwick’s Pavilion! Dear Parents and Carers, We have had another fantastic week here at DTA. On Wednesday we had Year 7 News the ‘Grand Opening’ of our new Sports Pavilion. The Major of Manchester Andy Burnham and ex Manchester United player Denis Irwin attended the Grand Opening and two of our pupils Ashah and Tanya from Year 9 Year 8 News presented our guests of honour with a poem they had written about how great Manchester is. Our VIPs took part in a penalty shoot-out with our very own Mr Fuller in goal and the afternoon was completed by the unveiling of Year 9 News the plaque and a question and answer session between Denis and DTA pupils. The weather played its part and was kind to us and a great afternoon Theme of the Week was had by all. We have started 1-1 careers advice for Year 9, please read on to find out more. Pavilion Grand Opening Attendance has dipped slightly since we returned from the Christmas break. I know a virus has been going around but if I could ask you to please send Inclusion your children into school unless they are seriously ill. Remember they miss valuable learning time if not in school and if your child becomes ill during the school day and needs to go home we will always ring you. -

NFGS Roundtable, AGM and Fgib

The National Forest Gardening Scheme CIC Saturday 28th September 2019 Gatherings in Manchester at Friends Of the Earth, Hulme Community Garden Centre & Birchfields Park Climate Resilience: Think & Act like a Forest Garden There are three parts to this document: 1. A report of the Round Table on Climate Resilience in Manchester 2. NFGS AGM proceedings 3. Workshop and Launch of prototype: ‘A Forest Garden in a Box’ PART ONE Report of the Round Table on Greater Manchester Climate Resilience and Forest Gardening The Roundtable at Green Fish Resource Centre (courtesy of Manchester FOE) was attended by twentythree people: Who Any relevant organisation Contact details (if you are affiliation willing to share) please add in Hannah Gardiner NFGS CIC director, Shared Assets... Jane Morris NFGS CIC director, Friends [email protected] of Birchfields Park... FOE Richard Luff NFGS CIC director … Oxford Paul Pivcevic NFGS CIC director ... Bath Phaedra NFGS CIC director... Wirral Hardstaff Amer Obeid … Trafford 1 Daniel RTPI & Oxford Scharf Richard … Herefordshire Green Network Urbanski [email protected] https://hgnetwork.org Tomas … author of ‘Forest Gardening in Remiarz Practice’ Joseph Agroforestry McCrohon Jo Barker East Kent Permaculture Network (Co-ordinator). [email protected] Permaculture Association (Trustee) Future Food Forests (Director) www.dynamic-equilibrium.co.uk Facebook: Jo Barker Permaculture Robert Social orchards ... London Walker Bernard Hulme Alliance Sudlow Jill Lovecy Manchester City Council Colin Manchester Permaculture Bennett Network... Friends of Platt Fields Jane Wood Salford...Poverty Truth Commission, Self Reliant Groups, [email protected] Salford City Radio, The Jane and Mike Band Jane Wood (facebook/messenger) The Jane and Mike Band at raspberry railings (facebook) Ivan Bedford.. -

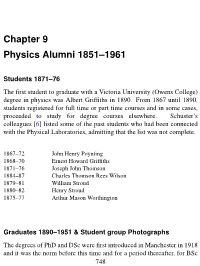

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961 Students 1871–76 The first student to graduate with a Victoria University (Owens College) degree in physics was Albert Griffiths in 1890. From 1867 until 1890, students registered for full time or part time courses and in some cases, proceeded to study for degree courses elsewhere. Schuster’s colleagues [6] listed some of the past students who had been connected with the Physical Laboratories, admitting that the list was not complete. 1867–72 John Henry Poynting 1868–70 Ernest Howard Griffiths 1871–76 Joseph John Thomson 1884–87 Charles Thomson Rees Wilson 1879–81 William Stroud 1880–82 Henry Stroud 1875–77 Arthur Mason Worthington Graduates 1890–1951 & Student group Photographs The degrees of PhD and DSc were first introduced in Manchester in 1918 and it was the norm before this time and for a period thereafter, for BSc 748 graduates to follow up with a one year MSc course. 1890 First Class: Albert Griffiths. Third Class: Ernest Edward Dentith Davies. Albert Griffiths Assoc. Owens 1890, MSc 1893, DSc 1899. After graduating, Albert Griffiths was a research student, fellow, demonstrator and lecturer at Owens between 1892 and 1898, in between posts at Freiburg, Southampton and Sheffield. He became Head of the Physics Department at Birkbeck in 1900. E E D Davies, born on the Isle of Man, obtained a BSc in mathematics in 1889, an MSc in 1892, a BA in 1893 before becoming a Congregational Minister in 1895. Joseph Thompson lists him [246], as a student at the Lancashire Independent College in 1893. -

Royal-Exchange.Pdf

{ A ROYAL WELCOME } to the newly refurbished Manchester Royal Exchange At the heart of one of the most historically rich and forward thinking cities in Europe stands Manchester Royal Exchange, where commerce and culture converge to create a Manchester landmark 1729 { exchange informationandstrikedeals. providing ameetingplaceforbusinessmento The firstexchangeonthissitewasopenedin1729 MAKING HISTORY SINCE 1729 1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 the titleof‘Royal’toorganisation. and herreceptionattheExchange,shegranted visittoManchester In 1851,afterQueenVictoria’s 1860 1760 1880 1890 1900 andThursdays. being Tuesdays had exceeded10,000withthedaysof‘HighChange’ By thebeginningoftwentiethcentury itsmembership 1910 1920 1930 1940 } 1950 Exchange building is The completely circular Royal The building is now listed Grade II (1974) Exchange Theatre is opened. Grade II listed. 2010 Refurbishment complete 1970 1990 2005 1960 1980 2010 2000 Dominating St. Ann’s Square, the Royal Exchange combines a nationally renowned theatre and a unique shopping experience coupled with high quality large floor plate office accommodation designed to meet the needs of a wide range of businesses. 07. St. Ann’s Square is the cultural centre of Manchester, satisfying the desire for an eclectic mix of shopping, café bars, leisure activities and business life, which combine to produce a thriving, stylish city centre utopia. Manchester Royal Exchange provides a newly refurbished large efficient floor plates Natural light floods the areas from three elevations and two fully re-clad internal lightwells. Natural ventilation is provided by double glazed window units. There are also dedicated entrances, the main entrance being from St. Ann’s Square with an additional entrance leading from Cross Street. 09. 11. Manchester Royal Exchange provides newly refurbished, large and efficient floor plates, capable of accommodating both open plan and cellular office layouts. -

Manchester-Visitor-Info-V.01.19.Pdf

Manchester Visitor Information What to see and do in Manchester Manchester is a city waiting to be discovered There is more to Manchester than meets the eye; it’s a city just waiting to be discovered. From superb shopping areas and exciting nightlife to a vibrant history and contrasting vistas, Manchester really has everything. It is a modern city that is Throw into the mix an dynamic, welcoming and impressive range of galleries energetic with stunning and museums (the majority architecture, fascinating of which offer free entry) and museums, award winning visitors are guaranteed to be attractions and a burgeoning stimulated and invigorated. restaurant and bar scene. Manchester has a compact Manchester is a hot-bed of and accessible city centre. cultural activity. From the All areas are within walking thriving and dominant music distance, but if you want scene which gave birth to to save energy, hop onto sons as diverse as Oasis and the Metrolink tram or jump the Halle Orchestra; to one of aboard the free Mettroshuttle the many world class festivals bus. and the rich sporting heritage. We hope you have a wonderful visit. Manchester History Manchester has a unique history and heritage from its early beginnings as the Roman Fort of ‘Mamucium’ [meaning breast-shape hill], to today’s reinvented vibrant and cosmopolitan city. Known as ‘King Cotton’ or ‘Cottonopolis’ during the 19th century, Manchester played a unique part in changing the world for future generations. The cotton and textile industry turned Manchester into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Leaders of commerce, science and technology, like John Dalton and Richard Arkwright, helped create a vibrant and thriving economy. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Resources and Governance

Public Document Pack Resources and Governance Scrutiny Committee Date: Thursday, 8 November 2018 Time: 2.00 pm Venue: Council Ante Chamber, Level 2, Town Hall Extension Everyone is welcome to attend this committee meeting. There will be a private meeting for Members only at 1.30pm in Committee Room 6 (Room 2006), 2nd Floor of Town Hall Extension Access to the Council Ante Chamber Public access to the Council Ante Chamber is on Level 2 of the Town Hall Extension, using the lift or stairs in the lobby of the Mount Street entrance to the Extension. That lobby can also be reached from the St. Peter’s Square entrance and from Library Walk. There is no public access from the Lloyd Street entrances of the Extension. Filming and broadcast of the meeting Meetings of the Resources and Governance Scrutiny Committee are ‘webcast’. These meetings are filmed and broadcast live on the Internet. If you attend this meeting you should be aware that you might be filmed and included in that transmission. Membership of the Resources and Governance Scrutiny Committee Councillors - Russell (Chair), Ahmed Ali, Andrews, Barrett, Clay, Davies, Lanchbury, Kilpatrick, R Moore, B Priest, Rowles, A Simcock, Watson and S Wheeler Resources and Governance Scrutiny Committee Agenda 1. Urgent Business To consider any items which the Chair has agreed to have submitted as urgent. 2. Appeals To consider any appeals from the public against refusal to allow inspection of background documents and/or the inclusion of items in the confidential part of the agenda. 3. Interests To allow Members an opportunity to [a] declare any personal, prejudicial or disclosable pecuniary interests they might have in any items which appear on this agenda; and [b] record any items from which they are precluded from voting as a result of Council Tax/Council rent arrears; [c] the existence and nature of party whipping arrangements in respect of any item to be considered at this meeting. -

(July 2018) Any Comments You Have on the Local Plan Issues Paper Can B

Regulation 18 Local Plan - Issues Paper Consultation Form (July 2018) Any comments you have on the Local Plan Issues Paper can be submitted using this consultation response form. Please note, not all questions are mandatory. Comments, using this form, can be submitted by email to [email protected] or by post to Strategic Planning, Strategic Growth Services, Trafford Council, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Manchester, M32 0TH. If you have any enquiries regarding the Local Plan Issues Paper, please email [email protected] or call 0161 912 3149 and a member of the Strategic Planning Team will be able to assist. Comments are invited on the Issues Paper from 23rd July 2018 until 14th September 2018 when the consultation will close. Data protection Please note all comments will be held by the Council and will be available to view publicly. Comments cannot be treated as confidential. Your personal information such as your postal and e-mail address will not be published, but your name and organisation (if relevant) will. Trafford Council maintains a database of consultees who wish to be kept informed about strategic planning matters such as the Local Plan. In responding to this consultation your contact details will automatically be added to the consultation database (if not already held). If you do not want to be on the consultation database and therefore not be contacted about future strategic planning consultations please state this in your response. Personal details Title Dr Forename Charlotte Surname Starkey Organisation (if applicable) Position/title (if applicable) Address Postcode Email address Landline phone no Mobile phone no If you are representing another person, please provide their details as follows: Title Forename Surname 1 | P a g e Organisation (if applicable) Position/title (if applicable) Address Postcode Email address Landline phone no Mobile phone no Scope and contents of the Local Plan Do you agree with the scope and contents of the Local Plan? No. -

Master Plan Historic Manchester

Community Profile ....................2 Master Plan Historic Manchester ..................3 for the City of Economic Vitality ......................4 Manchester, New Hampshire Adopted by the Planning Board December 10, 2009 Arts and Culture .......................5 Housing Opportunities .............6 Introduction Gateways & Corridors ...............7 he Master Plan provides a vision for the City of what Manchester could look like in the next ten to fifteen years. It focuses primarily on the Streetscapes .............................8 physical development of the community - the public facilities and infrastructure as well as the form, type and density of private Walkability ...............................9 Tdevelopment. In accordance with State law, the Plan provides a basis for the Alternative Transportation .....10 Zoning Ordinance which is the City’s primary tool for regulating the development of private parcels. The next phase following the Master Plan is the Traffic Management ................11 development of implementation strategies and projects. Trails .....................................12 A vibrant and healthy City requires a balance of a number of elements. These Recreational Opportunities ....13 include: a diversified and resilient economy; a variety of housing opportunities; consumer goods and other services; good schools and higher education; a Greening Manchester ..............14 sound public infrastructure of roads, utilities, sidewalks and municipal buildings; amenities and strong neighborhoods. This Master Plan discusses Sustainable City ......................15 each of these and other aspects and tries to bring an appropriate balance or mix for the future City. A community must also be prepared to address major Public Facilities ......................16 global changes such as climatic change and energy problems. This plan Neighborhoods ......................19 begins to discuss such global issues by discussing ways that Manchester can become more sustainable for future generations. -

The Mission Practices of New Church Congregations in Manchester City Centre

The mission practices of new church congregations in Manchester city centre Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Edson, John B. Citation Edson, B. (2006). An exploration into the missiology of the emerging church in the UK through the narrative of Sanctus1”. International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church: The Emerging Church, 6(1), 24-37.; Edson, B. (2008). The emerging church at the centre of the city. In P. Ballard (Ed.), The Church at the centre of the city (pp. 126-139). Peterborough: Epworth. Publisher University of Chester Download date 27/09/2021 20:26:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/314922 This work has been submitted to ChesterRep – the University of Chester’s online research repository http://chesterrep.openrepository.com Author(s): John Benedict Edson Title: The mission practices of new church congregations in Manchester city centre Date: October 2013 Originally published as: University of Liverpool MPhil thesis Example citation: Crowder, M. (2013). The mission practices of new church congregations in Manchester city centre. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Liverpool, United Kingdom. Version of item: Submitted version Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10034/314922 The Mission Practices of New Church Congregations in Manchester City Centre Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Master of Philosophy by John Benedict Edson October 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 4 Declarations 5 Abbreviations 6 Nature of Study 7 Chapter