Considerations on the Theme Park Model As Short-Term Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 2 (2020) Skin-Deep Gender: Posthumanity and the De(con)struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld Amaya Fernández Menicucci ABSTRACT: This article addresses the ways in which gender configurations are used as representations of the process of self-construction of both human and non-human characters in Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s series Westworld, produced by HBO and first launched in 2016. In particular, I explore the extent to which the process of genderization is deconstructed when human and non-human identities merge into a posthuman reality that is both material and virtual. In Westworld, both cyborg and human characters understand gender as embodiment, enactment, repetition, and codified communication. Yet, both sets of characters eventually face a process of disembodiment when their bodies are digitalized, which challenges the very nature of identity in general and gender identity in particular. Placing this digitalization of human identity against Donna Haraway’s cyborg theory and Judith Butler’s citational approach to gender identification, a question emerges, which neither Posthumanity Studies nor Gender Studies can ignore: can gender identities survive a process of disembodiment? Such, indeed, is the scenario portrayed in Westworld: a world in which bodies do not matter and gender is only skin-deep. KEYWORDS: Westworld; gender; posthumanity; embodiment; cyborg The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world. The cyborg is also the awful apocalyptic telos of the ‘West’s’ escalating dominations . (Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto 8) Revolution in a Post-Gender, Post-Race, Post-Class, Post-Western, Posthuman World The diegetic reality of the HBO series Westworld (2016-2018) opens up the possibility of a posthuman existence via the synthesis of individual human identities and personalities into algorithms and a post-corporeal digital life. -

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

Main Street, U.S.A. • Fantasyland• Frontierland• Adventureland• Tomorrowland• Liberty Square Fantasyland• Continued

L Guest Amenities Restrooms Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Tomorrowland® Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS AED ATTRACTIONS First Aid NEW! Presented by Florida Hospital 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad U 37 Tomorrowland Speedway 26 Enchanted Tales with Belle T AED Guest Relations Information and Lost & Found. AED 27 36 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® Be magically transported from Maurice’s cottage to E Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. ATMs 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ Beast’s library for a delightful storytelling experience. Fantasyland 26 Presented by CHASE AED 28 Package Pickup. Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. AED 27 Under the Sea~Journey of The Little Mermaid AED 34 38 Space Mountain® AAutomatedED External 35 Defibrillators ® Relive the tale of how one Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 23 S Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite ARunawayED train coaster. lucky little mermaid found true love—and legs! Designated smoking area 39 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s PhilharMagic. 21 32 Baby Care Center 33 40 Tomorrowland Transit Authority AED 28 Ariel’s Grotto Venture into a seaside grotto, Locker rentals 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island 16 PeopleMover Roll through Come explore the Island. where you’ll find Ariel amongst some of her treasures. -

Street, USA • Fantasyland• Continued Fantasyland• Frontierland

LEGE Guest Amenities Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Wishes Tomorrowland® Restrooms nighttime spectacular Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS First Aid ® See the skies of the Magic 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad 25 Mickey’s PhilharMagic 35 Tomorrowland Speedway Presented by Florida Hospital ® Kingdom light up with this Information and Lost & Found. 3D movie. Presented by Kodak . 34 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® nightly fireworks extravaganza Guest Relations Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ 26 Dream Along With Mickey that can be seen throughout ATMs Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. Presented by CHASE Package Pickup. Musical stage show. the entire Park! 32 36 Space Mountain® 23 33 Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. Automated External 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ® 27 Prince Charming Regal Carrousel See TIMES GUIDE. S Defibrillators Runaway train coaster. Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite 37 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Designated smoking area Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. 28 The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh 21 Fantasyland 30 31 Baby Care Center Roll, bounce and 38 Tomorrowland Transit Authority 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island float through indoor adventures (moments in 16 PeopleMover Roll through Locker rentals Come explore the Island. 6 Harmony Barber Shop the dark). FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s Liberty Square 24 27 Tomorrowland. -

Magic Kingdom

Mickey’s PhilharMagic Magic Kingdom 2 “it’s a small world” 8 ® 23 attractions ® 9 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic – 1 0 Dumbo the Flying Elephant® – 5 Join Donald on a musical 3-D Soar over Fantasyland. 4 6 7 movie adventure through Disney classics. Theater does 1 1 The Barnstormer® – become dark at times with Take to the sky with the occasional water spurts. Flying Goofini. 1 2 Buzz Lightyear’s Space 10 3 11 ® 2 “it’s a small world” – Sail off Ranger Spin – Zap aliens and fantasyland on a classic voyage around the save the galaxy. world. Inspired by Disney•Pixar’s “Toy Story 2.” 3 Peter Pan’s Flight – Take a 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic fl ight on a pirate ship. 1 3 Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor – An ever-changing, 4 Cinderella’s Golden interactive giggle fest starring BIG THUNDER Carrousel – Take a magical Mike Wazowski. Inspired by MOUNTAIN RAILROAD Dumbo ride on an enchanted horse. Disney·Pixar’s “Monsters, Inc.” the Flying 24 5 Dumbo the Flying Elephant – 14 Walt Disney World® Railroad Elephant Soar the skies with Dumbo. – Hop a steam train that makes stops at Frontierland, 6 The Many Adventures of Mickey’s Toontown TOMORROWLAND Fair and frontierland® Winnie the Pooh – Visit the Main Street, U.S.A. INDY SPEEDWAY Hundred Acre Wood. 1 5 The Magic Carpets of 16 7 Mad Tea Party Aladdin tomorrowland® – Go for – Fly high over 19 a spin in a giant teacup. the skies of Agrabah. 20 8 Pooh’s Playful Spot – 1 6 Country Bear Jamboree – 18 Dream-Along With 21 Outdoor play break area. -

The 50Th Magical Milestones Penny Machine Locations

Magical Milestones Penny Press Locations Magical Milestones Penny Press Locations This set has been retired and taken off-stage This set has been retired and taken off-stage Magical Milestones Pressed Penny Machine Locations List Magical Milestones Pressed Penny Machine Locations List Disneyland's 50th Anniversary Penny Set Disneyland's 50th Anniversary Penny Set Courtesy of ParkPennies.com ©2006 Courtesy of ParkPennies.com ©2006 Updated 10/2/06 Sorted by Magical Milestones Year Sorted by Machine Location YEAR Magical Milestones Theme 50th Penny Machine Location 1962 Swiss Family Tree House opens (1962) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1955 Opening Day of Disneyland ® park (July 17, 1955) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 2 1994 "The Lion King Celebration Parade" debuts (1994) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1956 Tom Sawyer Island opens (1956) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1999 Tarzan's Treehouse™ opens (1999) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 1 1957 House of the Future opens (1957) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 5 1956 Tom Sawyer Island opens (1956) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1958 Alice In Wonderland opens (1958) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 6 1963 Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room opens (1963) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1959 Disneyland® Monorail opens (1959) Disneyland Hotel - Fantasia Gift 1995 Indiana Jones Adventure™ - Temple of the Forbidden Eye open (1995) Adventureland - Raja's Mint Machine (in the Bazaar) # 2 1960 Parade of Toys debuts (1960) Main Street Disneyland - Penny Arcade Machine # 4 1965 Tencennial Celebration (1965) Disneyland Hotel - Fantasia Gift Shop The Disneyland® Hotel is purchased by The Walt Disney Co. -

Humanistic STEM: from Concept to Course

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 11 | Issue 1 January 2021 Humanistic STEM: From Concept to Course Debra T. Bourdeau WW/Humanities & Communication Beverly L. Wood ERAU-WW/STEM Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Bourdeau, D. T. and Wood, B. L. "Humanistic STEM: From Concept to Course," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 11 Issue 1 (January 2021), pages 33-53. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.202101.04 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol11/iss1/4 ©2021 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Humanistic STEM: From Concept to Course Debra T. Bourdeau WW/English and Humanities, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, USA [email protected] Beverly L. Wood Mathematics, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, USA [email protected] Abstract Blending perspectives from the humanities and STEM fosters the creativity of all students. The culturally implicit dichotomy between the two meta-disciplines can be overcome with carefully designed courses and programs intent on doing so. -

What to Know Walt Disney World Railroad – Show Starring All of the American Presidents

Mainstreet U.S.A. The Hall of Presidents – A film about the Tomorrowland United States Constitution and an Audio-Animatronics What to know Walt Disney World Railroad – show starring all of the American Presidents. Tomorrowland Indy Speedway – • Disney Characters greet you at Mickey’s Toontown Ride around Magic Kingdom Park in a Show time: 20 minutes. Miniature gas-powered cars offer big fun. Fair and other locations throughout the Park. You train pulled by a classic whistle-blowing Minimum height to ride alone: 132 cm. can also enjoy them in shows and parades. steam engine. Ride time: 20 minutes. Fantasyland Space Mountain – Popular roller • Each land in the Magic Kingdom Park features coaster ride proves that screams can be heard live entertainment. Pick up a Guidemap when Adventureland “it’s a small world” – Float past hundreds you enter the Park for times and information, of colourfully costumed dolls in this musical in outer space. Minimum height: 111.8 cm. or check the Tip Board. Swiss Family Treehouse – Tour a replica celebration of cultures. Walt Disney’s Carousel of Progress – An • For shorter wait times, visit the more popular of the Swiss Family Robinson’s giant banyan Audio-Animatronics classic first seen at the 1964 tree home. Peter Pan’s Flight – Fly to Never Land with attractions during parades or traditional dining periods. Peter Pan for adventures with Captain Hook World’s Fair in New York. Show time: 20 minutes. • Inside the Castle you’ll discover Cinderella’s Royal Table, a magical Jungle Cruise – Cruise through and a hungry crocodile. Tomorrowland Transit Authority – restaurant serving acclaimed chefs’ creations at lunch and dinner. -

Bwwaltdisneyworldcharacters

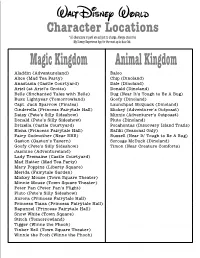

World Character Locations *All characters in park are subject to change. Always check the My Disney Experience App for the most up to date list. Magic Kingdom Animal Kingdom www.themeparkprofessor.comAladdin (Adventureland) www.themeparkprofessor.com www.themeparkprofessor.comBaloo www.themeparkprofessor.com Alice (Mad Tea Party) Chip (Dinoland) Anastasia (Castle Courtyard) Dale (Dinoland) Ariel (at Ariel’s Grotto) Donald (Dinoland) www.themeparkprofessor.comBelle (Enchanted www.themeparkprofessor.comTales with Belle) www.themeparkDug (Near professor.com It’s Tough www.themeparkprofessor.com to Be A Bug) Buzz Lightyear (Tomorrowland) Goofy (Dinoland) Capt. Jack Sparrow (Pirates) Launchpad McQuack (Dinoland) Cinderella (Princess Fairytale Hall) Mickey (Adventurer’s Outpoast) Daisy (Pete’s Silly Sideshow) Minnie (Adventurer’s Outpoast) www.themeparkprofessor.comDonald (Pete’s Silly www.themeparkprofessor.com Sideshow) www.themeparkprofessor.comPluto (Dinoland) www.themeparkprofessor.com Drizella (Castle Courtyard) Pocahontas (Discovery Island Trails) Elena (Princess Fairytale Hall) Rafiki (Seasonal Only) Fairy Godmother (Near BBB) Russell (Near It’ Tough to Be A Bug) www.themeparkprofessor.comGaston (Gaston’s www.themeparkprofessor.comTavern) www.themeparkprofessor.comScrooge McDuck (Dinoland) www.themeparkprofessor.com Goofy (Pete’s Silly Sideshow) Timon (Near Creature Comforts) Jasmine (Adventureland) Lady Tremaine (Castle Courtyard) www.themeparkprofessor.comMad Hatter (Mad www.themeparkprofessor.comTea Party) www.themeparkprofessor.com -

Subverting Or Reasserting? Westworld (2016-) As an Ambiguous Critical Allegory of Gender Struggles

#24 SUBVERTING OR REASSERTING? WESTWORLD (2016-) AS AN AMBIGUOUS CRITICAL ALLEGORY OF GENDER STRUGGLES Miguel Sebastián-Martín Universidad de Salamanca Ilustración || Isela Leduc Artículo || Recibido: 19/07/2020 | Apto Comité Científico: 04/11/2020 | Publicado: 01/2021 DOI: 10.1344/452f.2021.24.9 [email protected] Licencia || Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 3.0 License 129 Resumen || Este artículo analiza las tres primeras temporadas de la serie de HBO Westworld (2016-2020), considerándolas una alegoría crítica de las relaciones de género. Se presta especial atención a la construcción autorreflexiva de sus mundos de ciencia ficción y a dos de los arcos narrativos de los personajes principales, las androides femeninas (o ginoides) Dolores y Maeve. Más específicamente, el ensayo consiste en un examen dialéctico de las ambigüedades narrativas de la serie, por lo que su argumento es doble. Por un lado, se argumenta que Westworld está clara y conscientemente construida como una alegoría crítica y que, como tal, sus mundos de ciencia ficción escenifican luchas sociales reales (principalmente, aquellas entre géneros) para narrar posteriormente su (intento) de derrocamiento. Por otro lado, en contra de esta interpretación crítico-alegórica, pero completándola, también se argumenta que Westworld no es una narrativa inequívocamente crítica y que, si vamos a examinar sus potenciales alegóricos, debemos considerar también cómo su realización puede ser obstaculizada y/o contradicha por ciertas ambigüedades narrativas. Palabras clave || Westworld | Ciencia ficción | Metaficción | Alegoría crítica | Género Abstract || This article analyses the first three seasons of HBO’s Westworld (2016-2020) by considering them a critical allegory of gender relations. In so doing, the text pays special attention to the self-reflexive construction of its SF worlds, and to two of the main characters’ arcs, the female androids (or gynoids) Dolores and Maeve. -

How Theme Park Rides Adapted the Shooting Gallery

How Theme Park Rides Adapted the Shooting Gallery Bobby Schweizer Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas United States [email protected] Keywords Shooting galleries, theme parks, midways, arcades, media archeology EXTENDED ABSTRACT In 1998, Walt Disney Imagineering unveiled a new ride for Tomorrowland in the Magic Kingdom park in Orlando, Florida—one that introduced a new form of interactivity previously unseen in their parks. Buzz Lightyear Space Ranger Spin was a hybrid attraction: part dark ride, part shooting gallery. Riders boarded Omnimover vehicles armed with two blaster guns mounted to the dashboard that could be aimed with a limited range of motion to defeat the Emperor Zurg. An LCD screen tallied the score as passengers spun their vehicles to position themselves to shoot at “Z” marked targets throughout the blacklight neon ride. With the creation of this attraction and, most recently the opening of the Star Wars Millennium Falcon: Smuggler’s Run, the dark ride has seemingly adopted the values of videogame interactivity. Yet, while a comparison to videogames seems obvious, this transition did not happen overnight and was, in fact, part of a long tradition of target shooting forms of play. The shooting gallery has always been a perennial entertainment form seen in fairs, carnivals, and amusement parks across the globe (Adams 1991). Emerging out of military and marksmanship traditions, these games emulate the practice of real target shooting in which a marksman stands at one end of a booth or range while shooting pellets at stationary or moving targets (Tucker and Tucker 2014). Played for prizes or bragging right, the simple act of aiming and pulling a trigger has undergone technological adaptations to automate the process, place it into new venues, and create new feedback loops that construct new player experiences intended for social interaction. -

Westworld (2016-): a Transhuman Nightmare Or the Advancement of Posthumanism?

Cyborgs vs Humans in Westworld (2016-): A Transhuman Nightmare or the Advancement of Posthumanism? Izarbe Martín Gracia S2572737 Supervisor: Dr. E. J. van Leeuwen Second Reader: Prof. dr. P. T. M. G. Liebregts Master Thesis English Literature and Culture Leiden University March 2021 1 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One. Theoretical Framework: ............................................................................. 8 Transhumanism: The Enhancement of Human Intellect and Physiology ............... 9 Posthumanism: The Deconstruction of the Human .............................................. 14 Donna Haraway: The Cyborg and The Post-dualistic Society.............................. 18 The Western .......................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two. Sleep Mode .............................................................................................. 23 Section A. The Minds Behind the Project ............................................................. 24 Section B. Programming the Human Software ..................................................... 32 Chapter Three. Awakening ............................................................................................. 41 Section A. Insurrection at the Lab: Maeve and her Administrator Privileges ...... 43 Section B. The Search for Answers: Dolores.......................................................