Simon Stow in 2017, the BET Hip-Hop Awards Opened with A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. May 21, 2018 to Sun. May 27, 2018 Monday May 21, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Steve Winwood Nashville A smooth delivery, high-spirited melodies, and a velvet voice are what Steve Winwood brings When You’re Tired Of Breaking Other Hearts - Rayna tries to set the record straight about her to this fiery performance. Winwood performs classic hits like “Why Can’t We Live Together”, failed marriage during an appearance on Katie Couric’s talk show; Maddie tells a lie that leads to “Back in the High Life” and “Dear Mr. Fantasy”, then he wows the audience as his voice smolders dangerous consequences; Deacon is drawn to a pretty veterinarian. through “Can’t Find My Way Home”. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT The Big Interview Foreigner Phil Collins - Legendary singer-songwriter Phil Collins sits down with Dan Rather to talk about Since the beginning, guitarist Mick Jones has led Foreigner through decades of hit after hit. his anticipated return to the music scene, his record breaking success and a possible future In this intimate concert, listen to fan favorites like “Double Vision”, “Hot Blooded” and “Head partnership with Adele. Games”. 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT Presents Phil Collins - Going Back Fleetwood Mac, Live In Boston, Part One Filmed in the intimate surroundings of New York’s famous Roseland Ballroom, this is a real Mick, John, Lindsey, and Stevie unite for a passionate evening playing their biggest hits. -

Title Artist Key Capo 20 C 500 Miles Proclaimers E a Groovy Kind Of

Title Artist Key Capo 20 C 500 Miles Proclaimers E A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins C A House Is Not A Home Burt Bacharach Cm A night like this C Aber bitte mit Sahne Udo Jürgens F Abracadabra Steve Miller Am Achy Breaky Heart A Against All Odds Phil Collins Db Agua De Beber Dm Ai se eu te pego (Nossa Nossa) Michel Teló B Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Am Aint nobody Em All about that bass Meghan Trainor A all blues Miles Davis C All summer long Kid Rock G All that she wants st: Ace Of Base C#m All The Things You Are Bbm Amazing Grace Misc. Traditional C Angels Robbie Williams E Another One Bites The Dust Queen F#m At Last F Atemlos B Auf Uns D Autumn Leaves Nat King Cole Gm Baby I love you Artist Name C Back To Black Amy Winehouse Dm Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Revival G Baker Street Gerry Rafferty Ab Bamboleo Gipsy Kings F#m Beautiful Christina Aguilera Eb Believe F# Bergwerk D Besame Mucho Joao Gilberto Am Best (the) F Billy Jean Michael Jackson F#m Birds And The Bees Misc. Unsigned Bands D Black Horse And Cherry Tree Kt Tunstall Em Black magic woman Santana Dm Blue Bossa} Cm Blue Moon Elvis Presley Cb Bobby Brown Frank Zappa C Book of love Artist Name A Brazil G Bubbly A Bye Bye Blackbird Db Calm after the storm Artist Name Ab Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley D Can't wait until tonight_Max C Mutzke Candle In The Wind Elton John E Cocaine E Copacabana Barry Manilow Bbm Corazon espinado Bm Corcovado C Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Bm Country Roads 2 John Denver D Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen D Daddy Cool Boney -

Sample Song List Murphy Knows Over 2000+ Covers. Here Is Sample List Of

Acoustic 60’s to now 07807603836 [email protected] www.MurphyJamesMusic.com Sample Song List Murphy knows over 2000+ covers. Here is sample list of a few songs but there are many more that aren't on this list so please feel free to request anything else. If Murphy knows it, he will be sure to play it for you. 500 miles – The Proclaimers A little respect – Erasure A sky full of stars - Coldplay A thousand years – Christina Peri Africa - Toto Ain't no sunshine – Bill Withers Ain’t nobody – Chaka Khan Alcoholic – Starsailor All about you - McFly All I want is you – U2 All night long – Lionel Richie All of me – John Legend All the small things – Blink 182 Always on my mind – Elvis Presley America – Razorlight America – Neil Diamond American Pie – Don McClean Am I wrong – Nico & Vinz Angel of Harlem – U2 Angels – Robbie Williams Another brick in the wall – Pink Floyd Another day in Paradise – Phil Collins Apologize – One Republic Ashes – Embrace A sky full of stars - Coldplay A-team - Ed Sheeran Babel – Mumford & Sons Baby can I hold you – Tracy Chapman Baby I love your way – Peter Frampton Baby one more time – Britney Spears Babylon – David Gray Back for good – Take That Back to black – Amy Winehouse Bad moon rising – Credence Clearwater Revival Be mine – David Gray Be my baby – The Ronettes Beautiful noise – Neil Diamond Beautiful war – Kings of Leon Best of you – Foo Fighters Better – Tom Baxter Big love – Fleetwood Mac Big yellow taxi – Joni Mitchell Black and gold – Sam Sparro Black is the colour – Christie Moore Bloodstream -

Literatura Y Otras Artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and His Multiple Identities »

TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO « Literatura y otras artes: Hip Hop, Eminem and his multiple identities » Autor: Juan Muñoz De Palacio Tutor: Rafael Vélez Núñez GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico 2014-2015 Fecha de presentación 9/09/2015 FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS UNIVERSIDAD DE CÁDIZ INDEX INDEX ................................................................................................................................ 3 SUMMARIES AND KEY WORDS ........................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1. HIP HOP ................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. THE 4 ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 8 1.2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 10 1.3. WORLDWIDE RAP ............................................................................................................. 21 2. EMINEM ................................................................................................................. 25 2.1. BIOGRAPHICAL KEY FEATURES ............................................................................................. 25 2.2 RACE AND GENDER CONFLICTS ........................................................................................... -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Girl in Red - Serotonin Episode 208

Song Exploder girl in red - Serotonin Episode 208 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. Before this episode starts, I want to let you know that there is some frank discussion of mental health issues, including panic attacks, medical fears and thoughts of self-harm. There’s also some explicit language. (“Serotonin” by GIRL IN RED) Hrishikesh: Marie Ulven is a singer, songwriter, and producer from Norway, who makes music under the name, girl in red. She just released her debut album in April 2021, but she’s already got a lot of fans and she’s gotten a lot of critical acclaim from two EPs and singles that she’s released online, including a couple of songs that went gold. The New York Times included her work in their best songs of the year in both 2018 and 2019. Last year she was nominated for Best Newcomer at the Norwegian Grammys, and this year she won their award International Success of the Year. “Do you listen to girl in red?” has also become code on TikTok, a sort of shibboleth, to ask if someone’s a lesbian. In this episode, Marie breaks down the song “Serotonin,” a song that started as a video she posted to her own TikTok in the early days of lockdown in 2020. You’ll hear the original version she recorded on her own, before she started working with producer Matias Téllez, and later, with Grammy-winning artist and producer Finneas O’Connell, who helped finish the song. -

GRAB a GRAMMY the Big News of Last Month About How It Felt to Win the As You Probably Know the Has to Be the Fantastic Victory Best Alternative Album

1 News Updates COLDPLAY Coldplay Interview (10/99) Will Champion Profile E-ZINE • ISSUE 1 • 04.02 Interview with Phil Harvey GRAB A GRAMMY The Big News of last month about how it felt to win The As you probably know the has to be the fantastic victory Best Alternative Album. recording of the second at the 44th Annual Grammy Chris was thrilled: "Of course album is now complete and Awards. Jonny, Will, Guy and we're absolutely delighted to the mixing process has Phil were at the prestigious get this Grammy thing even begun. Chris also told me event in Los Angeles. though it's total nonsense, it's that he is very happy with the Chris was absent from the still good nonsense to win". results and assures me they have made a great album. ceremony as he was in I spoke to him just as the England in the studio working hour had swung into his 25th The band had a break after on the follow up to birthday and he was on his their time recording and Parachutes. I spoke to him way to the studio to play went off to do various things. Click to watch Interview piano. Chris visited the island of Haiti (Dominican Republic) as part of an Oxfam charity venture. This snippet is taken as it appeared in a local newspaper. British Coldplay rock star, Chris Martin, was in the DR last week. He came on an invitation from Oxfam United Kingdom to visit coffee farms in the southern province of San Cristobal. -

WDR 200 Beste Songs

WDR 200 Beste Songs Platz Künstler Titel Jahr 1 John Miles Music 1976 2 Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 3 Queen Bohemian Rhapsody 1975 4 John Lennon Imagine 1971 5 Runrig Loch lomond 1983 6 U2 One 1991 7 Phil Collins In the Air Tonight 1981 8 Eagles Hotel California 1976 9 Fury in the Slaughterhouse Time to Wonder 1988 10 Big Country Ships (Where Were You) 1993 11 Pink Floyd Wish You Were Here 1975 12 Modern Talking You’re My Heart, You’re My Soul 1984 13 Marillion Map of the World 2001 14 The Beatles Yesterday 1966 15 Indigo Girls Closer to Fine 1989 16 Wise Guys Jetzt Ist Sommer 2001 17 U2 With or Without You 1987 18 Alphaville Forever Young 1984 19 Uriah Heep Lady in Black 1971 20 Chris De Burgh A Woman’s Heart 1999 21 Heinz Rudolf Kunze Aller Herren Länder 1999 22 Deep Purple Smoke on the Water 1972 23 Dire Straits Brothers in Arms 1985 24 Toto Africa 1982 25 Roxette Milk and Toast and Honey 2001 26 Chris De Burgh Where Peaceful Waters Flow 1983 27 Elvis Presley In the Ghetto 1969 28 The Police Every Breath You Take 1983 29 The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 30 Ezio Angel Song 1993 31 BAP Verdamp Lang Her 1981 32 The Rolling Stones (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction 1965 33 Donnie Munro The Weaver of Grass 34 Pink Floyd Another Brick in the Wall 35 Kiss God Gave Rock 'n' Roll to You II 1991 36 Dire Straits Sultans of Swing 1978 37 Jean-Jacques Goldman Je Marche Seul 1985 38 Runrig Running to the Light 39 R.E.M. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

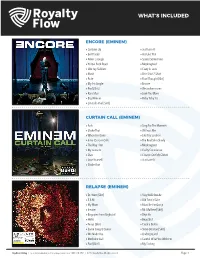

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow.