The Case of RL Stine's Give Yourself Goosebumps Gamebooks Via

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rl-Stine.Pdf

R.L. S&ne, born Robert Lawrence, was born in Columbus Ohio in 1943. He began wri&ng at the early age of nine, upon making a discovery that forever changed his life. It was in the late aernoon that Robert found an old family typewriter in the ac. It was said that he took this old typewriter to his room where he spent hours upon hours typing stories and jokes. His mother was said to have insisted that Robert stop typing and go outside and play. Robert felt going outside was boring and would oFen choose to write instead. His discovery later paid off in life because he never stopped wri&ng. AFer graduang from Ohio State University in 1965, Robert pursued his life’s dream of becoming a writer. He set off to New York where he wrote many books for kids. He created a humor magazine known as, Bananas which he contributed to for ten years. In those &mes he wrote under an alias known as, Jovial Bob S&ne. R.L. S&ne soon married a woman named Jane Waldhorn in 1969. Jane was an editor and writer herself, and she knew Robert’s talent had to be known. It was later that her and her partner formed their own publishing company known as, Parachute Press. This company would later help create all of Robert’s popular book series. In 1986, Robert wrote his first teen horror novel en&tled, Blind Date. It became an instant best seller and piqued his interest to pursue scary novels. -

The @Macaulay Author Series on Manhattan's West Side Continues with Acclaimed Goosebumps Author R.L

Press Office Press Contacts: Macaulay Honors College Grace Rapkin The City University of New York 212 729 2913 or [email protected] 35 West 67th Street New York, NY 10023 Lisa Dierbeck 917 364-0755 or [email protected] PRESS RELEASE THE @MACAULAY AUTHOR SERIES ON MANHATTAN'S WEST SIDE CONTINUES WITH ACCLAIMED GOOSEBUMPS AUTHOR R.L. STINE READING FROM, DISCUSSING AND SIGNING HIS FIRST NOVEL FOR ADULTS, RED RAIN, ON NOVEMBER 13, 2012 New York, NY (October 19, 2012) - The publishing community collaborates on an exciting new venture: the @Macaulay Author Series. Partnering with Macaulay Honors College at CUNY, in an historic building on West 67th Street just off Central Park, the series brings writers of the best in new fiction and nonfiction to a neighborhood teeming with culture consumers and booklovers. The series is a welcome return of author appearances for an area of the city currently under-served by bookstores and literary events. The monthly reading series continues with the goose-bumps-inducing R.L. STINE, who will share his first novel for adults, Red Rain (Touchstone/Simon&Schuster). Destined to become as enormous a best seller for grownups as his celebrated Goosebumps novels are for the young, Red Rain takes an unsuspecting travel writer to an isolated island off the South Carolina coast during hurricane season. But it's the storm's aftermath that confronts her with true horror. Mr. Stine's program takes place on Tuesday, November 13 from 7:00pm to 9:00pm. "Real characters, crisp writing, and a wicked sense of humor. -

INFORM ATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Arm Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE EXPLORATION OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS' INTERESTS IN AND ATTRACTIONS TO THE WRITINGS OF R. L. STINE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stacia A. -

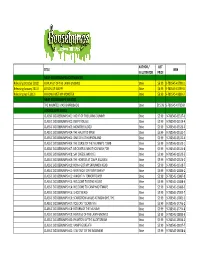

Goosebumps Series List.Pdf

AUTHOR / LIST TITLE ISBN ILLUSTRATOR PRICE NEW! GOOSEBUMPS MOST WANTED Releasing October 2012! #1 PLANET OF THE LAWN GNOMES Stine $6.99 9‐780545‐41798‐3 Releasing January 2013! #2 SON OF SLAPPY Stine $6.99 9‐780545‐41799‐0 Releasing April 2013! #3 HOW I MET MY MONSTER Stine $6.99 9‐780545‐41800‐3 NEW! GOOSEBUMPS WANTED THE HAUNTED MASK (HARDBACK) Stine $15.99 9‐780545‐41793‐8 GOOSEBUMPS SERIES CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #01: NIGHT OF THE LIVING DUMMY Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03517‐0 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #02: DEEP TROUBLE Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03519‐4 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #03: MONSTER BLOOD Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03520‐0 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #04: THE HAUNTED MASK Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03521‐7 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #05: ONE DAY AT HORRORLAND Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03522‐4 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #06: THE CURSE OF THE MUMMY'S TOMB Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03523‐1 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #07: BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03524‐8 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #08: SAY CHEESE AND DIE! Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03525‐5 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #09: THE HORROR AT CAMP JELLYJAM Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03526‐2 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #10: HOW I GOT MY SHRUNKEN HEAD Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐03518‐7 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #11: WEREWOLF OF FEVER SWAMP Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐15886‐2 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #12: A NIGHT IN TERROR TOWER Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐15887‐9 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #13: WELCOME TO DEAD HOUSE Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐15888‐6 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #14: WELCOME TO CAMP NIGHTMARE Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐15889‐3 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #15: GHOST BEACH Stine $5.99 9‐780545‐17803‐7 CLASSIC GOOSEBUMPS #16: SCARECROW -

Scholastic News October 17, 2012 News for Kids Who Read Books!

Scholastic News October 17, 2012 News for kids who read books! Scholastic Book Fairs Fall 2012 National Middle School Student Crew Enter for a chance to win a credit of 2,000 Scholas- tic Dollars™ redeemable through the Scholastic Book Fairs School Resource Catalog or at a Scholastic Book Fairs warehouse location, plus a visit to your school from Tom Angleberger, the author of the Origami Yoda books. RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. Contest open to middle schools, junior high schools, the 6th - 8th grade levels of K-8 schools, and the 6th - 8th grade levels of K-12 schools in the U.S. that use student volunteers (a Student Crew) to TABLE OF CONTENTS conduct a Scholastic Book Fair between May 9, 2012, and December 16, 2012. Entries must be Pg. 1 post-marked by midnight December 27, 2012. Void where prohibited by law. Assemblies will Scholastic Fall Book Fair and recognize the Book Fair achievements of the Rules Student Crew and will include a question and Pg. 2 answer exchange with students. A drawing for Prizes and How to Enter door prizes will also be conducted prior to the conclusion of each assembly. Appearance will Pg. 3 be targeted between April 2, 2013 and May 14, General Information and Winner 2013, depending on the winning school’s desire Selection and the availability of Tom Angleberger. Pg. 4 Goosebumps 20th Anniversary FIRST PLACE How to Enter One first-place winning school will receive a credit of 2,000 Scholastic Dollars redeemable through the Scholastic Book Fairs School Resource Catalog or Complete the official entry form at a Scholastic Book Fairs warehouse location, plus and send us your story about how a personal appearance by author Tom Angleberger. -

Some STINE-Tingling Facts

Some STINE-tingling Facts • More than 300 million Goosebumps books sold and an additional 100 million books sold of Stine’s THE NIGHTMARE ROOM, NIGHTMARE HOUR, and FEAR STREET series. • Goosebumps books published by Scholastic have been translated into more than 32 languages. • The 2003 Guinness Book of World Records named Stine the world’s bestselling children’s book series author of all time. • Scholastic Media launched the Goosebumps television show in 1995—which topped the ratings charts and aired in over 60 countries. • The Goosebumps television series currently airs on The Hub in the United States; it is available on DVD from Fox Home Entertainment and is available for download in iTunes. • USA Today named R.L. Stine the #1 best-selling author in America for three consecutive years during the 1990s. • Stine was included on People magazine’s list of the “25 Most Intriguing People of 1995.” • “Goosebumps” or “R.L. Stine” has been the answer to five different questions on the game show Jeopardy between 1998 and 2006. • @RL_Stine was listed as one of the “140 Best Twitter Feeds” by TIME.com. (March 2011) • Stine was selected to accompany First Lady Laura Bush to Russia to promote children’s reading in Moscow. (2003) • Awards: -Three-time winner of the Nickelodeon Kid’s Choice Award for Favorite Book -Three-time winner of the Disney Adventures Kids’ Choice Award for Best Book (Mystery/Horror) -Winner of the Thriller Writers of America Silver Bullet Award (2007) -The recipient of the first Champion of Reading Award from the Free Public Library of Philadelphia (2002) • R.L. -

R.L. Stine- Author of Famous Goosebumps Series Together! Can You Guess? Or Deliver to Them!

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 “Read. Read. Read. Just don’t read one type of book. Read different National National Farm World Card Homemade Animal Day Making Day! books, by many authors…” Cookies Day! Play farm animal Make a card for Make some cookies charades! How many someone and mail it R.L. Stine- Author of famous Goosebumps Series together! can you guess? or deliver to them! 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Fire Prevention World Teacher’s October has two International Kale Fire Prevention Make skeletons Week! Day! birthstones! Day! Happy Birthday, Day! using q-tips. Talk about your Write a letter to your The opal and Kale is a leaf, green R.L. Stine! Write a letter or draw Here’s how: family safety plan teacher(s) saying tourmaline. vegetable. It is called a picture for local fire how much you and practice it! Long ago, people a “superfood” Author of fighters. Deliver it to bit.ly/qtipskeletons appreciate them. believed an opal because it’s so good the station and thank brought good luck. for you! Try some ! Goosebumps Series them. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 October is National Columbus Day! Help your family Wednesday Drop Dictionary Day! National Pasta Bully Prevention Learn about cook dinner Writing! Everything Learn some new Day! Month. Christopher tonight. Afterwards, fancy words! Columbus: And Talk openly about help them clean Write a Halloween Have pasta for being a good friend Read up. story. It can funny Play Scrabble! dinner! and how to properly bit.ly/ccolumbusday or spooky! Then bit.ly/ccolumbusbook address any issues at share! at least 30 minutes school. -

USING GRAPHIC NOVELS with CHILDREN and TEENS a Guide for Teachers and Librarians

USING GRAPHIC NOVELS WITH CHILDREN AND TEENS A Guide for Teachers and Librarians www.scholastic.com/graphix USING Graphic NOVELS with CHILDREN AND TEENS What are graphic novels? A Guide for Teachers and Librarians In this context, the word “graphic” does not mean “adult” or “explicit.” Graphic novels are books written and illustrated in the style of a comic book. The term graphic novel was first popularized by Will Eisner to Graphic NOVELS ARE hot! distinguish his book A Contract with God (1978) from collections of newspaper comic strips. He described graphic novels as consisting of No longer an underground movement appealing to a small following of enthusiasts, graphic novels “sequential art”—a series of illustrations which, when viewed in order, have emerged as a growing segment of book publishing, and have become accepted by librarians tell a story. and educators as mainstream literature for children and young adults literature that powerfully motivates kids to read. Although today’s graphic novels are a recent phenomenon, this basic way of storytelling has been used in various forms for centuries—early cave Are graphic novels for you? Should you be taking a more serious look at this format? How might drawings, hieroglyphics, and medieval tapestries like the famous Bayeux Tapestry can be thought of as stories told in pictures. The term graphic graphic novels fit into your library collection, your curriculum, and your classroom? novel is now generally used to describe any book in a comic format that resembles a novel in length and narrative development. Want to know more? If so, this guide is for you. -

Goosebumps Wanted: the Haunted Mask R.L

SCHOLASTIC PAPERBACKS Goosebumps Wanted: The Haunted Mask R.L. Stine Summary For the first time ever, Goosebumps is in hard cover! Catch the series' most notorious characters-undead or alive... From horror master R.L. Stine come two new chilling stories in one spooky standalone: The Haunted Mask has returned and is determined to make this the worst night of your life! Where's the last place you would want to get stuck? A haunted pumpkin patch where the jack o'lanterns are after you! And watch for Goosebumps: Most Wanted, an all-new paperback series coming in the fall. Scholastic Paperbacks A Goosebumps Jacketed Hardcover 9780545417938 Pub Date: 7/1/12 (US, Can.) $15.99 Author Bio Hardback R.L. Stine's books have sold more than 300 million copies, making him one of the most popular children's authors in history. Besides Goosebumps, R.L. Stine has written series 240 pages Ages 8 to 12 including: Fear Street, Rotten School, Mostly Ghostly, The Nightmare Room, and Juvenile Fiction / Horror & Dangerous Girls. R.L. Stine lives in New York with his wife, Jane, and his King Charles Ghost Stories spaniel, Minnie. www.RLStine.com. JUV018000 Series: Goosebumps July 2012 - New Releases - Page 1 SCHOLASTIC PRESS Wings of Fire #1: The Dragonet Prophecy Tui T. Sutherland Summary A thrilling new series soars above the competition and redefines middle-grade fantasy fiction for a new generation! The seven dragon tribes have been at war for generations, locked in an endless battle over an ancient, lost treasure. A secret movement called the Talons of Peace is determined to bring an end to the fighting, with the help of a prophecy -- a foretelling that calls for great sacrifice. -

Download PDF « Goosebumps Horrorland Series Collection R L

YCGMBYJ9UO ^ Goosebumps Horrorland Series Collection R L Stine 10 Books Set (Revenge Of... Book Goosebumps Horrorland Series Collection R L Stine 10 Books Set (Revenge Of Th e Living Dummy, Dreep From Th e Deep, Monster Blood For Breakfast, Haunted . Say Ch eese, Camp Slith er, Strange Powers) By Stine R L To download Goosebumps Horrorland Series Collection R L Stine 10 Books Set (Revenge Of The Living Dummy, Dreep From The Deep, Monster Blood For Breakfast, Haunted . Say Cheese, Camp Slither, Strange Powers) PDF, remember to click the hyperlink listed below and save the document or have accessibility to other information which might be relevant to GOOSEBUMPS HORRORLAND SERIES COLLECTION R L STINE 10 BOOKS SET (REVENGE OF THE LIVING DUMMY, DREEP FROM THE DEEP, MONSTER BLOOD FOR BREAKFAST, HAUNTED . SAY CHEESE, CAMP SLITHER, STRANGE POWERS) ebook. Our website was released with a aspire to work as a comprehensive on the internet electronic collection which offers entry to large number of PDF file document collection. You will probably find many kinds of e-guide and also other literatures from our files data bank. Specific popular topics that spread out on our catalog are famous books, solution key, exam test questions and answer, guide paper, exercise guide, test test, user manual, user guide, assistance instruction, fix guide, and so forth. READ ONLINE [ 6.92 MB ] Reviews A must buy book if you need to adding benefit. It can be rally interesting throgh looking at period of time. Its been designed in an remarkably simple way and it is only after i finished reading this publication by which in fact altered me, modify the way i believe. -

Goosebumps(Second Draft 12-17-12) Script

Goosebumps by Darren Lemke HALL JEFFDecember 18th, 2012 FADE IN: EXT. - CHICAGO; LAKESHORE DRIVE - LATE NIGHT Rain comes down in buckets. A MOVING TRUCK is parked out front of a Gothic, pre-war APARTMENT BUILDING. Stone gargoyles sit perched above. Thunder crashes bringing us to- INT. - APARTMENT 313; LIVING ROOM Dark wood. High ceilings. As charming as a haunted mansion. Near deserted, the bare rooms are filled with over-stuffed MOVING BOXES--all marked FRAGILE. Lightning flashes revealing- AN ANTIQUE DUMMY sealed within a sturdy glass display case. A mischievous grin is frozen on the dummy’s inanimate wooden face like a child with a secret. Then- A LANKY MOVER loads the display case onto a hand truck. Nearby, a BURLY MOVER abrasively grabs a box when- APARTMENT OWNER (o.s.) Careful with those. The Burly Mover turns as we reveal a figure in the shadows-- for now, we’ll simply know him as the APARTMENT OWNER. In his hand is a STRESS BALL. APARTMENT OWNERHALL They’re very delicate. With that, the Apartment Owner gives the stress ball a squeeze then disappears back into the darkness. The Burly Mover rolls his eyes and follows the Lanky Mover out. As he does we notice that the apartment is badly damaged. Broken floors. Shattered walls. The movers exchange curious glances. BURLY MOVER (under his breath) What, did a bulldozer go through this place? JEFFLANKY MOVER (under his breath) That’s why landlords created security deposits. With that the two movers continue on their way. EXT. - STREET - MOMENTS LATER As the Lanky Mover loads the dummy into the truck- BURLY MOVER Heads up. -

The R.L. Stine Writing Program Teaching Guide

THE R.L. STINE WRITING PROGRAM TEACHING GUIDE GRADES 3–8 Dear Educator, As I travel around the country meeting students, so many children tell me they want to be writers. At the same time, teachers often tell me that their students— even good students—lack the skills and confidence to write clearly and well. In this age of computers and instant information, the ability to express oneself in writing is of paramount importance. And as many educators have pointed out to me, a greater writing facility often leads to more facility in reading and to overall school success. That’s one of the reasons I started THE R.L. STINE WRITING PROGRAM in my hometown, Bexley, Ohio— a program where professional writers come into the schools and work on writing with children. When I visit schools and talk to kids, they all ask the same questions: Where do you get your ideas?— and what do you do when you can’t think of anything to write? There is no doubt that kids ask these questions because they are looking for help when they sit down and confront a blank page. All of the activities and techniques I’ve included in this guide are designed to help students get over their anxiety about writing. I hope that while working with this material, they will learn that everyone has access to many ideas—and that no page or computer screen needs to stay blank for long. I hope your students find this program fun and helpful. As many readers know, I scare kids for a living, but I want them to know that when it comes to writing, there’s nothing scary about it! Have a Scary Day, R.L.