National Register of Historic Places JUN23 Multiple Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effective January 24, 2021 LIMITED EXPRESS ROUTES LOCAL

WESLEY CHAPELCHAPEL LOCAL ROUTES Calusa Tr ace BlBlv & HARTFLEX vdd.. Van Dyke RdRd.. St. Joseph’s Hospital - North ALL SERVICE MAPS LOCAL ONLY EXPRESS ONLY 33 WESLEY CHAPELCHAPEL NORTHDALE Lakeview D r . LUTZ SYSTEM MAP Gaither High TAMPA PALMS School Effective January 24, 2021 NNoorthda le B lv d. e. Sinclair Hills Rd. e. Av Av LEGEND LEGEND LEGEND Be . ars d s v l A Local Route Key Destinations Key Destinations B Ehrlich Rd. v s B 44 e n # and Route Number . w Route 33 does not 22nd St. 22nd St. Livingston Livingston ce BB. Do Hidden Local Route and Route Number Express Route Bru serve Hidden River 12 Calusa Skipper Rd.Rd. River Limited Express Route 20X20X Express routes marked by an X Tr Park-n-Ride on Park-n-Riderk-n-Ride ace BlvBl 44 AdventHealthventHealth Weekends # and Route Number Downtown to UATC CITRUS PARK vdd.. 1 42 400 Westeldsteld Fletcher Ave. 42 - Tampa 33 LX Limited Express routes See route schedule for details Limited Express Route Citrus Park @ Dale MabMabrryy Hwy. Stop P marked by an LX 75LX Mall Van Dyke RdRd.. 33 6 Fletcher Ave. Limited Express routes marked by an LX HARTFlex Zone St. Joseph’s Fletcher Ave. 33 400 FLEX e. HospitalCARROLLWOOCARROLLWOOD - North D e. 33 HARTFlex Route See route schedule for details 39 GunnGun H 48 Park-n-Ride Lots Av n Hwwy. 33 Av y. 131st Ave. University P B HARTFleHARTFlexx HARTFlex Route Vanpool Option Locations Walmart of South HARTFlex Zone See route schedule for details NORTHDALE Lakeview 45 Call TBARTA at (800) 998-RIDE (7433) e. -

West End Tampa Tampa, Florida

West End Tampa Tampa, Florida MORIN DEVELOPMENT GROUP 1510 West Cleveland Street, Tampa FL 33606 Telephone 813-258-2958 Fax 813-258-2959 1 The information above has been obtained from sources believed reliable. While we do not doubt its accuracy we have not verified it and make no guarantee, warranty or representation about it. It is your responsibility to independently confirm its accuracy and completeness. Table of Contents • Development Summary • Site Plans • Block A • Block B • Block C • Block D • Block E • Block F • Block G • North B Town Homes • Market Information • About Us 2 West End Tampa West End Tampa is a 20-acre master planned, family community comprised of apartments, town homes, condominiums and retail features. It is centrally located between the region’ s two largest business centers – Downtown Tampa (within 1 mile) and the West Shore Business District (within 3 miles). West End is encircled by major medical centers including Tampa General, Memorial and St. Joseph’s hospitals. It is situated within blocks of the nationally accredited University of Tampa. The West End community incorporates architectural sensitivity with ample, open public spaces to create a livinggyg environment that is distinctly different from the existing inventory of “Urban Lifestyle” product which is prevalent today. Contributing to the lifestyle balance of West End Tampa are parks, public art, recreational areas, pools, fitness centers and a convenient business center. Retail and Commercial…………………….25,000 Sq. Ft. of “neighborhood retail” spacece Office………………………………………...4, 500 Sq. Ft. of “Class A ” office space UNITS HEIGHT BEDROOMS SQ. FT. Condominiums 346 4-5 stories 2 & 3 630 – 1,600 Town Homes 79 3stories3 stories 2&32 & 3 16231,623 – 21132,113 Apartments 3 The Vintage Lofts 249 4 stories 1, 2 & 3 740 – 1,250 Logan Park 296 8 stories 1 & 2 737 – 1,204 West End Location West End Tampa is bordered to the south by Tampa’s charming Hyde Park neighborhood. -

Ffifi** REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL Parm This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 RECEIVED 2280 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JAN 1 9 2008 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES NAl F EGlSTEROFh ffifi** REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL PARm This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_____________________________________________________ historic name ROBLES. HORACE T. HOUSE________________________________________ other names/site number Robles Family Home_______________________________________ 2. Location street & number 2604 East Hanna Avenue N/A D not for publication city or town Tampa ___N/A D vicinity state FLORIDA code FL county Hillsborough _code 057 zio code 33610 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this El nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property I3 meets O does not meet the National Register criteria. -

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018 Completed For: In Cooperation with: Hillsborough County Metropolitan Planning Organization City of Tampa, Transportation Division 601 East Kennedy Boulevard, 18th Floor 306 East Jackson Street, 6th Floor East Tampa, FL 33601 Tampa, FL 33602 Task Authorization: TOA – 09 Prepared By: Tindale Oliver 1000 N Ashley Drive, Suite 400 Tampa, FL 33602 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f) of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. The MPO does not discriminate in any of its programs or services. Public participation is solicited by the MPO without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, family or religious status. Learn more about our commitment to nondiscrimination and diversity by contacting our Title VI/Nondiscrimination Coordinator, Johnny Wong at (813) 273‐3774 ext. 370 or [email protected]. WEST TAMPA MULTIMODAL PLAN Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction and Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

TRI-COUNTY BPAC MEETING SUMMARY – January 23, 2019 4

TRI-COUNTY BICYCLE PEDESTRIAN ADVISORY COMMITTEE (BPAC) HILLSBOROUGH, PASCO AND PINELLAS COUNTIES Wednesday, May 22, 2019, 6:00 PM – 7:30 PM Oldsmar State Street Center, 127 State Street W, Oldsmar, FL 34677 Please feel free to enjoy a ride, jog or stroll on your own before the meeting in beautiful Oldsmar. Be Safe. Meeting begins at 6:00 pm. AGENDA 1. CALL TO ORDER & INTRODUCTIONS 2. PUBLIC COMMENT (Limit to 3 minutes, please) 3. APPROVAL OF TRI-COUNTY BPAC MEETING SUMMARY – January 23, 2019 4. FLORIDA BICYCLE ASSOCIATION Becky Alfonso, FBA Executive Director 5. Advantage Pinellas: Active Transportation Plan Update Rodney Chatman, Forward Pinellas Division Manager 6. Gulf Coast Trail Wayfinding Wade Reynolds, Hillsborough MPO Senior Planner 7. St. Petersburg Complete Streets Program Cheryl Stacks, St. Petersburg Transportation Manager 8. ROUNDTABLE UPDATES: Forward Pinellas Hillsborough MPO Pasco MPO FDOT 9. DISCUSSION ITEMS: Electric Scooters Gateway Master Plan 10. NEW BUSINESS | OLD BUSINESS 11. NEXT TRI-COUNTY BPAC MEETING – September 25, 2019 (Host: Pasco BPAC) 12. ADJOURNMENT NEXT TRI-COUNTY BPAC MEETING: Wednesday, September 25, 2019 Pasco County BPAC to host (location TBD) TRI-COUNTY BICYCLE PEDESTRIAN ADVISORY COMMITTEE (BPAC) HILLSBOROUGH, PASCO AND PINELLAS COUNTIES West Tampa Library, 2312 W. Union Street, Tampa FL 33607 JANUARY 23, 2019 Meeting Summary 1. CALL TO ORDER & INTRODUCTIONS The meeting was called to order at 5:35 pm. In attendance: Jonathan Forbes, Wade Reynolds, Rodney Chatman, Ross Kevlin, Joel Jackson, David Feller, Richard Ranck, Sally Thompson, Susan J. Miller, Joan Rice, Jim Wedlake, Tania German, Gunther Flaig, Michele Ogilvie. 2. PUBLIC COMMENT Public Comment: Written: Christine Acosta: I would like to confirm what David Green said, that TBARTA will not be fulfilling any role with trails going forward. -

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017 6800 North Dale Mabry Highway, Suite 158 Tampa, FL 33614 PH (813) 515-2340 FAX (813) 435-2299 www.elchc.org The Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County (ELCHC) is a 501(c)(3), not for profit organization working to advance the access, affordability and quality of early childhood care and education programs in Hillsborough County. Through our Quality Counts for Kids Quality Improvement Program (QCFK) and a host of other resources and supports, we help child care centers and family child care homes to improve their program quality so that all children have quality early learning experiences. Contents How to Use this Quality Listing 4 What is Quality & Why Does it Matter? 5 Programs with Star Rating and/or Gold Seal Accreditation 6 Child Care Centers 7 Family Child Care Homes 19 Programs with a Class One Violation 24 Child Care Centers 25 Family Child Care Homes 26 Resources 28 Special Note/Disclaimer: The information provided in this booklet is gathered from public sources and databases as a courtesy. The information is considered accurate at the time of publication. Due to potential changes in provider/program status during the time period between when this information is gathered, printed and distributed, we encourage you to verify a provider’s status as part of your quality child care shopping efforts. The ELCHC does not individually endorse or recommend one provider or early childhood program over another whether or not they are listed within. January - June 2017 | 3 How to Use this Quality Listing Choosing child care is an important decision that requires last 12 months between November 1, 2015 to October 31, 2016. -

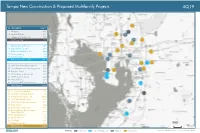

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Wildgrass 321 3 Union on Fletcher 217 5 Harbour at Westshore, The 192 Total Lease Up 730 15 Bowery Bayside Phase II 589 16 Tapestry Town Center 287 17 Pointe on Westshore, The 444 28 Victory Landing 69 29 Belmont Glen 75 Total Under Construction 1,464 36 Westshore Plaza Redevelopment 500 37 Leisey Road Mixed Used Development 380 38 Progress Village 291 39 Grand Cypress Apartments 324 43 MetWest International 424 44 Waverly Terrace 214 45 University Mall Redevelopment 100 Total Planned 2,233 69 3011 West Gandy Blvd 80 74 Westshore Crossing Phase II 72 76 Village at Crosstown, The 3,000 83 3015 North Rocky Point 180 84 6370 North Nebraska Avenue 114 85 Kirby Street 100 86 Bowels Road Mixed-Use 101 87 Bruce B Downs Blvd & Tampa Palms Blvd West 252 88 Brandon Preserve 200 89 Lemon Avenue 88 90 City Edge 120 117 NoHo Residential 218 Total Prospective 4,525 2 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Tampa New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 4 Central on Orange Lake, The 85 6 Main Street Landing 80 13 Sawgrass Creek Phase II 143 Total Lease Up 308 20 Meres Crossing 236 21 Haven at Hunter's Lake, The 241 Total Under Construction 477 54 Bexley North - Parcel 5 Phase 1 208 55 Cypress Town Center 230 56 Enclave at Wesley Chapel 142 57 Trinity Pines Preserve Townhomes 60 58 Spring Center 750 Total Planned 1,390 108 Arbours at Saddle Oaks 264 109 Lexington Oaks Plaza 200 110 Trillium Blvd 160 111 -

Hillsborough County Trails, Paths & Bicycle Guide

Get Inspired to Bike! to Inspired Get Davis Island Trail Island Davis at the Suncoast Trail and other local trails. local other and Trail Suncoast the at 200 feet. This system will soon be available available be soon will system This feet. 200 used bicycle paths. bicycle used Yellow numbered decals are placed every every placed are decals numbered Yellow trick-skating maneuvers on heavily heavily on maneuvers trick-skating rules as bicyclists. Do not perform perform not Do bicyclists. as rules their location within one of these trails. trails. these of one within location their costs; and improved quality of life. of quality improved and costs; Skaters should follow the same travel travel same the follow should Skaters • Greenway can easily tell first responders responders first tell easily can Greenway and other chronic diseases; lower health care care health lower diseases; chronic other and Tampa Bay Trail and Town ‘N Country Country ‘N Town and Trail Bay Tampa safely on the left. left. the on safely reduced risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, stroke, disease, heart coronary of risk reduced Number System. Trail users at the Upper Upper the at users Trail System. Number when approaching others, then pass pass then others, approaching when way. benefits for people of all ages, including including ages, all of people for benefits counties to implement a 911 Station Station 911 a implement to counties Sound your bell or call out a warning warning a out call or bell your Sound • Pedestrians always have the right-of- the have always Pedestrians • Regular bicycling carries many health health many carries bicycling Regular Hillsborough County is one of the first first the of one is County Hillsborough Signal to Other Cyclists Other to Signal pedestrians. -

Transforming Tampa's Tomorrow

TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Recommended Operating and Capital Budget Part 2 Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Jane Castor, Mayor Sonya C. Little, Chief Financial Officer Michael D. Perry, Budget Officer ii Table of Contents Part 2 - FY2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget FY2020 – FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 1 FY2020–FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 2 Council District 4 Map . 14 Council District 5 Map . 17 Council District 6 Map . 20 Council District 7 Map . 23 Capital Improvement Program Summaries . 25 Capital Improvement Projects Funded Projects Summary . 26 Capital Improvement Projects Funding Source Summary . 31 Community Investment Tax FY2020-FY2024 . 32 Operational Impacts of Capital Improvement Projects . 33 Capital Improvements Section (CIS) Schedule . 38 Capital Project Detail . 47 Convention Center . 47 Facility Management . 49 Fire Rescue . 70 Golf Courses . 74 Non-Departmental . 78 Parking . 81 Parks and Recreation . 95 Solid Waste . 122 Technology & Innovation . 132 Tampa Police Department . 138 Transportation . 140 Stormwater . 216 Wastewater . 280 Water . 354 Debt . 409 Overview . 410 Summary of City-issued Debt . 410 Primary Types of Debt . 410 Bond Covenants . 411 Continuing Disclosure . 411 Total Principal Debt Composition of City Issued Debt . 412 Principal Outstanding Debt (Governmental & Enterprise) . 413 Rating Agency Analysis . 414 Principal Debt Composition . 416 Governmental Bonds . 416 Governmental Loans . 418 Enterprise Bonds . 419 Enterprise State Revolving Loans . 420 FY2020 Debt Service Schedule . 421 Governmental Debt Service . 421 Enterprise Debt Service . 422 Index . -

Perry Harvey, Sr. Park: a Journey Into Tampa's History

Perry Harvey, Sr. Park: A Journey into Tampa’s History Celebrating history Celebrating The Scrub important part in the history of the city of Tampa. Over the years, the Central Avenue has a special place neighborhood of The Scrub developed in Tampa’s history, particularly for the a vibrant business district, and became African-American community, and a cultural mecca of sorts for a number the Perry Harvey, Sr. Park, located at of black musicians. 900 E. Scott St., will be a place where The area was booming, but began generations can come together to share to decline with urban renewal and in that history, to learn and enjoy. The integration. In 1967, the shooting of a improvements for Perry Harvey, Sr. Park 19-year-old black man resulted in three celebrate the history of Central Avenue, days of rioting, which contributed to its community leaders and cultural the downturn of the area. influences. In 1974, the last of the buildings The strength of the Tampa along Central Avenue, Henry community is built on its history. Joyner's Cotton Club, was closed and Central Avenue was the heart and demolished. Central Avenue Cotton Club soul of a community flourishing with Photo from Arthenia Joyner Five years later, in 1979, Perry leadership, entrepreneurship, strength Harvey, Sr. Park was developed at the and courage. request of local youth, looking for a The area was settled after the Civil place of their own to recreate near their War, when freed slaves relocated to Perry Harvey, Sr. homes. Photo from Harvey family an area northeast of downtown Tampa The park was named after Perry called The Scrub. -

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017 Jan 2017 QualityBooklet .indd 1 12/13/16 4:47 PM 6800 North Dale Mabry Highway, Suite 158 Tampa, FL 33614 PH (813) 515-2340 FAX (813) 435-2299 www.elchc.org The Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County (ELCHC) is a 501(c)(3), not for profit organization working to advance the access, affordability and quality of early childhood care and education programs in Hillsborough County. Through our Quality Counts for Kids Quality Improvement Program (QCFK) and a host of other resources and supports, we help child care centers and family child care homes to improve their program quality so that all children have quality early learning experiences. Jan 2017 QualityBooklet .indd 2 12/13/16 4:47 PM Contents How to Use this Quality Listing 4 What is Quality & Why Does it Matter? 5 Programs with Star Rating and/or Gold Seal Accreditation 6 Child Care Centers 7 Family Child Care Homes 19 Programs with a Class One Violation 24 Child Care Centers 25 Family Child Care Homes 26 Resources 28 Special Note/Disclaimer: The information provided in this booklet is gathered from public sources and databases as a courtesy. The information is considered accurate at the time of publication. Due to potential changes in provider/program status during the time period between when this information is gathered, printed and distributed, we encourage you to verify a provider’s status as part of your quality child care shopping efforts. The ELCHC does not individually endorse or recommend one provider or early childhood program over another whether or not they are listed within. -

TAMPA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1977-78 M Rs

Sunland Tribune Volume 4 Article 1 1978 Full Issue Sunland Tribune Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Tribune, Sunland (1978) "Full Issue," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 4 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol4/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SUNLAND TRIBUNE On Our Cover Volume IV Number 1 November, 1978 Old post card depicts Gordon Keller Journal of the Memorial Hospital, a "permanent TAMPA monument" to the memory of City HISTORICAL SOCIETY Treasurer and merchant Gordon Tampa, Florida Keller. HAMPTON DUNN Editor -Photo from HAMPTON DUNN COLLECTION Officers DR. L. GLENN WESTFALL 7DEOHRI&RQWHQWV President MRS. DAVID McCLAIN GORDON WHO? GORDON KELLER 2 Vice President By Hampton Dunn MRS. MARTHA TURNER Corresponding Secretary TAMPA HEIGHTS: MRS. THOMAS MURPHY TAMPA'S FIRST RESIDENTIAL SUBURB 6 Recording Secretary By Marston C. Leonard MRS. DONN GREGORY Treasurer FAMOUS CHART RECOVERED 11 Board of Directors I REMEMBER AUNT KATE 12 Mrs. A. M. Barrow Dr. James W. Covington By Lula Joughin Dovi Hampton Dunn Mrs. James L. Ferman Mrs. Joanne Frasier THE STORY OF DAVIS ISLANDS 1924-1926 16 Mrs. Thomas L. Giddens By Dr. James W. Covington Mrs. Donn Gregory Mrs. John R. Himes Mrs. Samuel 1. Latimer, Jr. DR. HOWELL TYSON LYKES Marston C. (Bob) Leonard Mrs. David McClain FOUNDER OF AN EMPIRE 30 Mrs. Thomas Murphy By James M.