Arxiv:1910.03010V3 [Math.RT] 1 Dec 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Directed Graphs Or Quivers What Is Category Theory? • Graph Theory on Steroids • Comic Book Mathematics • Abstract Nonsense • the Secret Dictionary

1. Directed graphs or quivers What is category theory? • Graph theory on steroids • Comic book mathematics • Abstract nonsense • The secret dictionary Sets and classes: For S = fX j X2 = Xg, have S 2 S , S2 = S Directed graph or quiver: C = (C0;C1;@0 : C1 ! C0;@1 : C1 ! C0) Class C0 of objects, vertices, points, . Class C1 of morphisms, (directed) edges, arrows, . For x; y 2 C0, write C(x; y) := ff 2 C1 j @0f = x; @1f = yg f 2C1 tail, domain / @0f / @1f o head, codomain op Opposite or dual graph of C = (C0;C1;@0;@1) is C = (C0;C1;@1;@0) Graph homomorphism F : D ! C has object part F0 : D0 ! C0 and morphism part F1 : D1 ! C1 with @i ◦ F1(f) = F0 ◦ @i(f) for i = 0; 1. Graph isomorphism has bijective object and morphism parts. Poset (X; ≤): set X with reflexive, antisymmetric, transitive order ≤ Hasse diagram of poset (X; ≤): x ! y if y covers x, i.e., x 6= y and [x; y] = fx; yg, so x ≤ z ≤ y ) z = x or z = y. Hasse diagram of (N; ≤) is 0 / 1 / 2 / 3 / ::: Hasse diagram of (f1; 2; 3; 6g; j ) is 3 / 6 O O 1 / 2 1 2 2. Categories Category: Quiver C = (C0;C1;@0 : C1 ! C0;@1 : C1 ! C0) with: • composition: 8 x; y; z 2 C0 ; C(x; y) × C(y; z) ! C(x; z); (f; g) 7! g ◦ f • satisfying associativity: 8 x; y; z; t 2 C0 ; 8 (f; g; h) 2 C(x; y) × C(y; z) × C(z; t) ; h ◦ (g ◦ f) = (h ◦ g) ◦ f y iS qq <SSSS g qq << SSS f qqq h◦g < SSSS qq << SSS qq g◦f < SSS xqq << SS z Vo VV < x VVVV << VVVV < VVVV << h VVVV < h◦(g◦f)=(h◦g)◦f VVVV < VVV+ t • identities: 8 x; y; z 2 C0 ; 9 1y 2 C(y; y) : 8 f 2 C(x; y) ; 1y ◦ f = f and 8 g 2 C(y; z) ; g ◦ 1y = g f y o x MM MM 1y g MM MMM f MMM M& zo g y Example: N0 = fxg ; N1 = N ; 1x = 0 ; 8 m; n 2 N ; n◦m = m+n ; | one object, lots of arrows [monoid of natural numbers under addition] 4 x / x Equation: 3 + 5 = 4 + 4 Commuting diagram: 3 4 x / x 5 ( 1 if m ≤ n; Example: N1 = N ; 8 m; n 2 N ; jN(m; n)j = 0 otherwise | lots of objects, lots of arrows [poset (N; ≤) as a category] These two examples are small categories: have a set of morphisms. -

An Exercise on Source and Sink Mutations of Acyclic Quivers∗

An exercise on source and sink mutations of acyclic quivers∗ Darij Grinberg November 27, 2018 In this note, we will use the following notations (which come from Lampe’s notes [Lampe, §2.1.1]): • A quiver means a tuple Q = (Q0, Q1, s, t), where Q0 and Q1 are two finite sets and where s and t are two maps from Q1 to Q0. We call the elements of Q0 the vertices of the quiver Q, and we call the elements of Q1 the arrows of the quiver Q. For every e 2 Q1, we call s (e) the starting point of e (and we say that e starts at s (e)), and we call t (e) the terminal point of e (and we say that e ends at t (e)). Furthermore, if e 2 Q1, then we say that e is an arrow from s (e) to t (e). So the notion of a quiver is one of many different versions of the notion of a finite directed graph. (Notice that it is a version which allows multiple arrows, and which distinguishes between them – i.e., the quiver stores not just the information of how many arrows there are from a vertex to another, but it actually has them all as distinguishable objects in Q1. Lampe himself seems to later tacitly switch to a different notion of quivers, where edges from a given to vertex to another are indistinguishable and only exist as a number. This does not matter for the next exercise, which works just as well with either notion of a quiver; but I just wanted to have it mentioned.) • The underlying undirected graph of a quiver Q = (Q0, Q1, s, t) is defined as the undirected multigraph with vertex set Q0 and edge multiset ffs (e) , t (e)g j e 2 Q1gmultiset . -

Higher-Dimensional Instantons on Cones Over Sasaki-Einstein Spaces and Coulomb Branches for 3-Dimensional N = 4 Gauge Theories

Two aspects of gauge theories higher-dimensional instantons on cones over Sasaki-Einstein spaces and Coulomb branches for 3-dimensional N = 4 gauge theories Von der Fakultät für Mathematik und Physik der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften – Dr. rer. nat. – genehmigte Dissertation von Dipl.-Phys. Marcus Sperling, geboren am 11. 10. 1987 in Wismar 2016 Eingereicht am 23.05.2016 Referent: Prof. Olaf Lechtenfeld Korreferent: Prof. Roger Bielawski Korreferent: Prof. Amihay Hanany Tag der Promotion: 19.07.2016 ii Abstract Solitons and instantons are crucial in modern field theory, which includes high energy physics and string theory, but also condensed matter physics and optics. This thesis is concerned with two appearances of solitonic objects: higher-dimensional instantons arising as supersymme- try condition in heterotic (flux-)compactifications, and monopole operators that describe the Coulomb branch of gauge theories in 2+1 dimensions with 8 supercharges. In PartI we analyse the generalised instanton equations on conical extensions of Sasaki- Einstein manifolds. Due to a certain equivariant ansatz, the instanton equations are reduced to a set of coupled, non-linear, ordinary first order differential equations for matrix-valued functions. For the metric Calabi-Yau cone, the instanton equations are the Hermitian Yang-Mills equations and we exploit their geometric structure to gain insights in the structure of the matrix equations. The presented analysis relies strongly on methods used in the context of Nahm equations. For non-Kähler conical extensions, focusing on the string theoretically interesting 6-dimensional case, we first of all construct the relevant SU(3)-structures on the conical extensions and subsequently derive the corresponding matrix equations. -

Quiver Indices and Abelianization from Jeffrey-Kirwan Residues Arxiv

Prepared for submission to JHEP arXiv:1907.01354v2 Quiver indices and Abelianization from Jeffrey-Kirwan residues Guillaume Beaujard,1 Swapnamay Mondal,2 Boris Pioline1 1 Laboratoire de Physique Th´eoriqueet Hautes Energies (LPTHE), UMR 7589 CNRS-Sorbonne Universit´e,Campus Pierre et Marie Curie, 4 place Jussieu, F-75005 Paris, France 2 International Centre for Theoretical Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Shivakote, Hesaraghatta, Bangalore 560089, India e-mail: fpioline,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In quiver quantum mechanics with 4 supercharges, supersymmetric ground states are known to be in one-to-one correspondence with Dolbeault cohomology classes on the moduli space of stable quiver representations. Using supersymmetric localization, the refined Witten index can be expressed as a residue integral with a specific contour prescription, originally due to Jeffrey and Kirwan, depending on the stability parameters. On the other hand, the physical picture of quiver quantum mechanics describing interactions of BPS black holes predicts that the refined Witten index of a non-Abelian quiver can be expressed as a sum of indices for Abelian quivers, weighted by `single-centered invariants'. In the case of quivers without oriented loops, we show that this decomposition naturally arises from the residue formula, as a consequence of applying the Cauchy-Bose identity to the vector multiplet contributions. For quivers with loops, the same procedure produces a natural decomposition of the single-centered invariants, which remains to be elucidated. In the process, we clarify some under-appreciated aspects of the localization formula. Part of the results reported herein have been obtained by implementing the Jeffrey-Kirwan residue formula in a public arXiv:1907.01354v2 [hep-th] 15 Oct 2019 Mathematica code. -

![Arxiv:2012.08669V1 [Math.CT] 15 Dec 2020 2 Preface](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5681/arxiv-2012-08669v1-math-ct-15-dec-2020-2-preface-995681.webp)

Arxiv:2012.08669V1 [Math.CT] 15 Dec 2020 2 Preface

Sheaf Theory Through Examples (Abridged Version) Daniel Rosiak December 12, 2020 arXiv:2012.08669v1 [math.CT] 15 Dec 2020 2 Preface After circulating an earlier version of this work among colleagues back in 2018, with the initial aim of providing a gentle and example-heavy introduction to sheaves aimed at a less specialized audience than is typical, I was encouraged by the feedback of readers, many of whom found the manuscript (or portions thereof) helpful; this encouragement led me to continue to make various additions and modifications over the years. The project is now under contract with the MIT Press, which would publish it as an open access book in 2021 or early 2022. In the meantime, a number of readers have encouraged me to make available at least a portion of the book through arXiv. The present version represents a little more than two-thirds of what the professionally edited and published book would contain: the fifth chapter and a concluding chapter are missing from this version. The fifth chapter is dedicated to toposes, a number of more involved applications of sheaves (including to the \n- queens problem" in chess, Schreier graphs for self-similar groups, cellular automata, and more), and discussion of constructions and examples from cohesive toposes. Feedback or comments on the present work can be directed to the author's personal email, and would of course be appreciated. 3 4 Contents Introduction 7 0.1 An Invitation . .7 0.2 A First Pass at the Idea of a Sheaf . 11 0.3 Outline of Contents . 20 1 Categorical Fundamentals for Sheaves 23 1.1 Categorical Preliminaries . -

Lectures on Representations of Quivers by William Crawley-Boevey

Lectures on Representations of Quivers by William Crawley-Boevey Contents §1. Path algebras. 3 §2. Bricks . 9 §3. The variety of representations . .11 §4. Dynkin and Euclidean diagrams. .15 §5. Finite representation type . .19 §6. More homological algebra . .21 §7. Euclidean case. Preprojectives and preinjectives . .25 §8. Euclidean case. Regular modules. .28 §9. Euclidean case. Regular simples and roots. .32 §10. Further topics . .36 1 A 'quiver' is a directed graph, and a representation is defined by a vector space for each vertex and a linear map for each arrow. The theory of representations of quivers touches linear algebra, invariant theory, finite dimensional algebras, free ideal rings, Kac-Moody Lie algebras, and many other fields. These are the notes for a course of eight lectures given in Oxford in spring 1992. My aim was the classification of the representations for the ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Euclidean diagrams A , D , E , E , E . It seemed ambitious for eight n n 6 7 8 lectures, but turned out to be easier than I expected. The Dynkin case is analysed using an argument of J.Tits, P.Gabriel and C.M.Ringel, which involves actions of algebraic groups, a study of root systems, and some clever homological algebra. The Euclidean case is treated using the same tools, and in addition the Auslander-Reiten translations - , , and the notion of a 'regular uniserial module'. I have avoided the use of reflection functors, Auslander-Reiten sequences, and case-by-case analyses. The prerequisites for this course are quite modest, consisting of the basic 1 notions about rings and modules; a little homological algebra, up to Ext ¡ n and long exact sequences; the Zariski topology on ; and maybe some ideas from category theory. -

QUIVERS and PATH ALGEBRAS 1. Definitions Definition 1. a Quiver Q

QUIVERS AND PATH ALGEBRAS JIM STARK 1. Definitions Definition 1. A quiver Q is a finite directed graph. Specifically Q = (Q0;Q1; s; t) consists of the following four data: • A finite set Q0 called the vertex set. • A finite set Q1 called the edge set. • A function s: Q1 ! Q0 called the source function. • A function t: Q1 ! Q0 called the target function. This is nothing more than a finite directed graph. We allow loops and multiple edges. The only difference is that instead of defining the edges as ordered pairs of vertices we define them as their own set and use the functions s and t to determine the source and target of an edge. Definition 2. A (possibly empty) sequence of edges p = αnαn−1 ··· α1 is called a path in Q if t(αi) = s(αi+1) for all appropriate i. If p is a non-empty path we say that the length of p is `(p) = n, the source of p is s(α1), and the target of p is t(αn). For an empty path we must choose a vertex from Q0 to be both the source and target of p and we say `(p) = 0. Note that paths are read right to left as in composition of functions. Though the source and target functions of a quiver are defined on edges and not on paths we will abuse notation and write s(p) and t(p) for the source and target of a path p. If p and q are paths in Q such that t(q) = s(p) then we can form the composite path pq. -

![[Hep-Th] 19 Aug 2021 Learning Scattering Amplitudes by Heart](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0979/hep-th-19-aug-2021-learning-scattering-amplitudes-by-heart-1890979.webp)

[Hep-Th] 19 Aug 2021 Learning Scattering Amplitudes by Heart

Learning scattering amplitudes by heart Severin Barmeier∗ Hausdorff Research Institute for Mathematics, Poppelsdorfer Allee 45, 53115 Bonn, Germany Albert-Ludwigs-Universit¨at Freiburg, Ernst-Zermelo-Str. 1, 79104 Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany Koushik Ray† Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Calcutta 700 032, India Abstract The canonical forms associated to scattering amplitudes of planar Feynman dia- grams are interpreted in terms of masses of projectives, defined as the modulus of their central charges, in the hearts of certain t-structures of derived categories of quiver representations and, equivalently, in terms of cluster tilting objects of the corresponding cluster categories. arXiv:2101.02884v4 [hep-th] 1 Sep 2021 ∗email: [email protected] †email: [email protected] 1 Introduction The amplituhedron program of N = 4 supersymmetric Yang–Mills theories [1] culminat- ing in the ABHY construction [2] has provided renewed impetus to the study of compu- tation of scattering amplitudes in quantum field theories, even without supersymmetry, using geometric ideas. While homological methods for the evaluation of Feynman dia- grams have been pursued for a long time [3], the ABHY program associates the geometry of Grassmannians to the amplitudes [4]. Relations of amplitudes to a variety of mathe- matical notions and structures have been unearthed [5–7]. For scalar field theories the amplitudes are expressed in terms of Lorentz-invariant Mandelstam variables. The space of Mandelstam variables is known as the kinematic space. The combinatorial structure of the amplitudes associated with the planar Feynman diagrams of the cubic scalar field theory is captured by writing those as differential forms associated to a polytope in the kinematic space, called the associahedron, and their integrals. -

Invitation to Quiver Representation and Catalan Combinatorics

Snapshots of modern mathematics № 4/2021 from Oberwolfach Invitation to quiver representation and Catalan combinatorics Baptiste Rognerud Representation theory is an area of mathematics that deals with abstract algebraic structures and has nu- merous applications across disciplines. In this snap- shot, we will talk about the representation theory of a class of objects called quivers and relate them to the fantastic combinatorics of the Catalan numbers. 1 Quiver representation and a Danish game Representation theory is based on the idea of taking your favorite mathematical object and looking at how it acts on a simpler object. In fact, it allows you to choose from a wide range of objects and play around with them. 1 Usually, the goal is to understand your favorite object better using the mathematics of the simpler object. But you can also do the opposite: you can use your favorite object to solve a problem related to the simpler object instead. For example, the famous Rubik’s cube can be solved using the action of finite groups (of size 227314537211) consisting of all the moves on the cube preserving it. The representation theory of finite groups was invented at the end of the 19th century and was heavily studied in the 20th century. This culminated in deep, (yet!) unsolved problems and has played a huge part in the classification of finite simple groups. 1 Historically, the first examples had a finite group as the first object and a vector space or a finite set as the second object. We refer to the snapshot by Eugenio Giannelli and Jay Taylor [3] for an introduction to this setting. -

Valued Graphs and the Representation Theory of Lie Algebras

Axioms 2012, 1, 111-148; doi:10.3390/axioms1020111 OPEN ACCESS axioms ISSN 2075-1680 www.mdpi.com/journal/axioms Article Valued Graphs and the Representation Theory of Lie Algebras Joel Lemay Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, K1N 6N5, Canada; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-613-562-5800 (ext. 2104) Received: 13 February 2012; in revised form: 20 June 2012 / Accepted: 20 June 2012 / Published: 4 July 2012 Abstract: Quivers (directed graphs), species (a generalization of quivers) and their representations play a key role in many areas of mathematics including combinatorics, geometry, and algebra. Their importance is especially apparent in their applications to the representation theory of associative algebras, Lie algebras, and quantum groups. In this paper, we discuss the most important results in the representation theory of species, such as Dlab and Ringel’s extension of Gabriel’s theorem, which classifies all species of finite and tame representation type. We also explain the link between species and K-species (where K is a field). Namely, we show that the category of K-species can be viewed as a subcategory of the category of species. Furthermore, we prove two results about the structure of the tensor ring of a species containing no oriented cycles. Specifically, we prove that two such species have isomorphic tensor rings if and only if they are isomorphic as “crushed” species, and we show that if K is a perfect field, then the tensor algebra of a K-species tensored with the algebraic closure of K is isomorphic to, or Morita equivalent to, the path algebra of a quiver. -

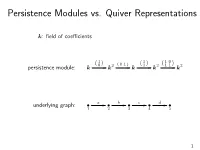

Persistence Modules Vs. Quiver Representations

Persistence Modules vs. Quiver Representations k: field of coefficients 1 1 1 0 ( 0 ) ( 0 1 ) ( 1 ) ( 1 1 ) persistence module: k / k2 / k / k2 / k2 underlying graph: • a • b • c • d • 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 1 Persistence Modules vs. Quiver Representations k: field of coefficients 1 1 1 0 ( 0 ) ( 0 1 ) ( 1 ) ( 1 1 ) quiver representation: k / k2 / k / k2 / k2 quiver: • a • b • c • d • 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 1 Outline • quivers and representations • the category of representations • the classification problem • Gabriel's theorem(s) • proof of Gabriel's theorem • beyond Gabriel's theorem 2 Quivers and Representations Definition: A quiver Q consists of two sets Q0;Q1 and two maps s; t : Q1 ! Q0. The elements in Q0 are called the vertices of Q, while those roughly speaking, a quiver is a (potentially infinite) directed multigraph of Q1 are called the arrows. The source map s assigns a source sa to every arrow a 2 Q1, while the target map t assigns a target ta. Ln(n ≥ 1) • • ··· • • 1 / 2 / n/ −1 / n 3 Quivers and Representations Definition: A quiver Q consists of two sets Q0;Q1 and two maps s; t : Q1 ! Q0. The elements in Q0 are called the vertices of Q, while those roughly speaking, a quiver is a (potentially infinite) directed multigraph of Q1 are called the arrows. The source map s assigns a source sa to every arrow a 2 Q1, while the target map t assigns a target ta. •1 • ? _ a _ e b d - • • • • 2 c / 3 Q Q¯ 3 Quivers and Representations Definition: A representation of Q over a field k is a pair V = (Vi; va) consisting of a set of k-vector spaces fVi j i 2 Q0g together with a set of k-linear maps fva : Vsa ! Vta j a 2 Q1g. -

Quiver Representations

University of Seville Degree Final Dissertation Double Degree in Physics and Mathematics Quiver Representations Javier Linares Tutor: Prof. Fernando Muro June 2019 Abstract A quiver representation is a collection of vector spaces and linear maps indexed by a directed graph: the quiver. In this paper we intend to give an introduction to the theory of quiver representations developing basic techniques that allow us to give a proof of Gabriel’s Theorem [Gab72]: A connected quiver is of finite type if and only if its underlying graph is a Dynkin diagram. This surprising theorem has a second part which links isomorphism classes of indecomposable representations of a given quiver with the root system of the graph underlying such a quiver. Throughout this project, we study the category of quiver representations from an algebraic approach, viewing representations as modules and using tools from homological algebra, but also from a geometrical point of view, defining quiver varieties and studying the corresponding root systems. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. First definitions and examples 2 3. Path algebras 6 4. The standard resolution 9 5. Bricks 14 6. The variety of representations RepQ(α) 16 7. Dynkin and Euclidean diagrams: classification 19 8. Gabriel’s Theorem 23 9. Conclusions 24 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1. Introduction Broadly speaking, representation theory is the branch of mathematics which studies symmetry in linear spaces. Its beginning corresponds to the early twentieth century with the work of German mathematician F.G. Frobenius. During the 30s, Emmy Noether gave a more modern view interpreting representations as modules. Since then, algebraic objects such as groups, associative algebras or Lie algebras have been studied within the framework of this theory, where the idea is representing elements of a certain algebraic structure as linear transformations in a vector space, giving rise to an infinite number of applications in number theory, geometry, probability theory, quantum mechanics or quantum field theory, among others.