Historics Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystal Color Chart

CRYSTAL COLOR GUIDE IV (hotfix & no hotfix) SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS flat back colors Merchants Overseas Updated 03.02.2011 Crystal Dark Siam Turquoise Sunflower White Opal Burgundy Pacific Opal Jonquil Chalkwhite Light Amethyst Mint Alabaster Silk Provence Caribbean Blue White Albaster Light Peach Lavender Opal Light Colorado Vintage Rose Tanzanite Blue Zircon Topaz Light Rose Cyclamen Opal Chrysolite Topaz Rose Amethyst Chrysolite Opal Smoked Topaz New! Indian Pink Purple Velvet Peridot Mocca Fuchsia Dark Indigo Fern Green Sand Opal Ruby Cobalt Blue Erinite Light Grey Opal Medium Padparadscha Greige Dark Sapphire Emerald Sun Montana Emerald Black Diamond Palace Green Fireopal Capri Blue Opal Jet Hyacinth Sapphire Olivine www.MerchantsOverseas.com [email protected] Light Siam Light Sapphire Khaki RI - t 800.333.4144 • f 401.331.5676 NY - t 800.714.7714 • f 212.714.0027 Indian Siam Air Blue Opal Citrine Light Your #1 Source for All Things Crystal! Siam Aquamarine Topaz Colors shown are a best approximation of actual stone colors. CRYSTAL COLOR GUIDE V SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS Flat Back Effects (no hotfix) Merchants Overseas Updated 03.02.2011 Crystal Peridot Crystal Bermuda Crystal Dorado Aurore Boreale “AB” Aurore Boreale Blue Jonquil Crystal Crystal Meridian Jet Nut Aurore Boreale Moonlight Blue Topaz Crystal Silver Crystal Metallic Crystal Silver Aurore Boreale Shade Blue Night Light Rose Crystal Golden Crystal Sahara Jet Hematite Aurore Boreale Shadow Rose Crystal Copper Crystal Sage Crystal Cosmojet Aurore Boreale Light Siam Crystal -

Of 3 Printed 8/12/2020

H:\1BIG TIME BACK-UP\1All uploading\1Stitch Emporium\SEE232 Flower Animals\for uploading\SEE232_ART Page 1 of 3 Printed 8/12/2020 1. White (Def:13) 14. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 1. White (Def:13) 14. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 2. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 15. Black (Def:14) 2. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 15. Black (Def:14) 3. Charcoal (Mar:1178) 16. White (Def:13) 3. Charcoal (Mar:1178) 16. White (Def:13) 4. Black (Def:14) 17. Light Navy (Mar:1448) 4. Black (Def:14) 17. Light Navy (Mar:1448) 5. White (Def:13) 18. Mauve (Mar:1076) 5. White (Def:13) 18. Mauve (Mar:1076) 6. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 19. Maroon (Mar:1155) 6. Dark Silver (Mar:1319) 19. Maroon (Mar:1155) 7. Charcoal (Mar:1178) 20. Black (Def:14) 7. Charcoal (Mar:1178) 20. Black (Def:14) 8. Toast (Mar:1130) 21. Light Navy (Mar:1448) 8. Toast (Mar:1130) 21. Light Navy (Mar:1448) 9. Tan (Mar:1141) 22. Maroon (Mar:1155) 9. Tan (Mar:1141) 22. Maroon (Mar:1155) 10. White (Def:13) 23. Mauve (Mar:1076) 10. White (Def:13) 23. Mauve (Mar:1076) 11. Black (Def:14) 24. Maroon (Mar:1155) 11. Black (Def:14) 24. Maroon (Mar:1155) 12. Mauve (Mar:1076) 25. Black (Def:14) 12. Mauve (Mar:1076) 25. Black (Def:14) 13. Light Navy (Mar:1448) 13. Light Navy (Mar:1448) See232_flower_animals_01.art50 See232_flower_animals_01_4x4.art50 4.99x6.71 inches; 39,563 stitches 2.90x3.91 inches; 20,257 stitches 25 thread changes; 9 colors 25 thread changes; 9 colors 1. -

You Can Also Download a PDF Copy Here

Interior Design in a Tin Selecting the Perfect Finish Honestly Colourful “I have been an interior designer Paints We are authentic, ethical and transparent in everything we do. for over 30 years, combining colour Our wall paint is best applied by roller and because there is no plastic in our paint it won’t create and tonality in my designs. I used to an orange peel effect. It is easy to apply, durable and wipeable. Plastic Free Ingredients mix my own colours using traditional There is no fossil fuel derived plastic in We declare ALL our ingredients as we our wall paint. Most modern paint is made think you should know exactly what you materials because I could never find Coverage No. VOC Breathability Sheen Surface Finish Description Spray the right colour and I saw just how (m2 /l) Coats (gm/l) (Sd value) (%) from plastic and will contain microbeads. are putting on your walls. superior these paints were to dull, Walls Emulsion Soft & Matt 12 2 <0.1 (0.07%) <0.1 Yes 2 modern equivalents. Breathability Kind To Nature Off White, Our paint is 20 times more breathable Based on gentle, plant based chemistry Ceiling Emulsion Matt 12 2 <0.1 (0.07%) <0.1 Yes 2 So I offer you what I want for my own than most modern paint – perfect for lime we know that our natural paint is the plaster and old walls and more durable safest, healthiest and most beautiful projects – beautiful colour and proven Wood & Water Based Durable, 13 2 <0.1 (0.08%) <0.3 Yes 30 Metal Eggshell* Satin than clay paint. -

Broadleigh, 1982

The small bulb specialists Broadlei Gardens Barr House Bishops Hull Taunton : Somerset Tel:Taunton 86231 Further to our circular letter sent to all overseas customers last year, in which I explained that we were not exporting due to the fact that Lord Skelmers- dale is now working permanently in London and consequently we are short-staffed have found that re-organisation has taken longer than anticipated and have, therefore, decided that this year we willnot -offer our usual range of bulbs for export. Instead we give hereunder a list of some of our rarest miniature hybrid and species Narcissi,which are all that we are sending out in 1982 to those requiring phytosanitary certificates. I do hope you will find something to interest you. As previously, our terms of business are that we cannot accept orders un ,',er £15 in value, excluding postage. Pre-payment is required to cover the cost of the bulbs but the exact cost of air mail postage will be notified at time of despatch and accounts adjusted accordingly. Bulbs are always sent by air mail unless we are requested not to do so. No discounts are allowed on overseas orders as considerable time is taken in special cleaning, etc. Name Divis- Description Ht Flower- Price ion ing Time Each Andainsta- 6 Cyc-lamineus hybrid, yellow 7" Late 4.00 with orange cup Apr. atlanticus x rupicola A new self-yellow jonquil 71, Mar 2.00 7 pedu-eularis hybrid. Quite exceptional. Scented. bulbocodium cantabricus 10 A pure white hoop petticoat 5u Dec/Jan .90 bulbocodium romieuxii 10 A pale lemon-yellow bulbocodium 4" Feb .50 eystettensis (Queen 4 I=fect su17hur - ycllow 6" Early 4.00 Anne's Double) double. -

70 SOLID COLORS for All Rubber Tile and Tread Profiles (Excluding Smooth and Hammered R24); Rubber and Vinyl Wall Base; and Rubber Accessories)

70 SOLID COLORS For all rubber tile and tread profiles (excluding Smooth and Hammered R24); rubber and vinyl wall base; and rubber accessories) Q 100 177 Q 150 Q 193 Q 123 Q 114 Q 129 Q 178 black steel blue dark gray black brown charcoal lunar dust dolphin pewter Q 194 148 Q 175 Q 174 197 Q 110 burnt umber steel gray slate smoke iceberg brown Q 147 Q 182 Q 623 Q 624 Q 140 Q 191 Q 125 171 light brown toffee nutmeg chameleon fawn camel fig sandstone Q 130 Q 198 Q 632 Q 184 Q 170 Q 131 127 Q 631 buckskin ivory flax almond white bisque harvest yellow sahara Q 639 640 Q 122 Q 195 663 648 647 646 beigewood creekbed natural light gray aged fern pear green spring dill gecko 160 649 169 662 118 187 139 627 forest green sweet basil hunter green envy peacock blue deep navy mariner 618 665 664 656 654 638 637 655 aubergine horizon blue jay bluebell lagoon cadet night mist peaceful blue 657 658 621 659 186 137 188 617 sorbet berry ice merlin grape red cinnabar brick terracotta 660 661 643 644 642 645 Q 641 Q 161 citrus marmalade mimosa sunbeam jonquil blonde moonrise snow MARBLEIZED COLORS For all rubber tile and tread profiles (excluding Hammered R24). M100 M177 M150 M193 M123 M114 M129 M178 black steel blue dark gray black brown charcoal lunar dust dolphin pewter M194 M148 M175 M174 M197 M110 burnt umber steel gray slate smoke iceberg brown M147 M182 M623 M624 M140 M191 M125 M171 light brown toffee nutmeg chameleon fawn camel fig sandstone M130 M198 M632 M184 M170 M131 M127 M631 buckskin ivory flax almond white bisque harvest yellow sahara M639 M640 -

Sherwin Williams Prism Paints

Item Number Color Name Color Code SW0001 Mulberry Silk PASTEL SW0002 Chelsea Mauve PASTEL SW0003 Cabbage Rose PASTEL SW0004 Rose Brocade DEEPTONE SW0005 Deepest Mauve DEEPTONE SW0006 Toile Red DEEPTONE SW0007 Decorous Amber DEEPTONE SW0008 Cajun Red DEEPTONE SW0009 Eastlake Gold DEEPTONE SW0010 Wickerwork PASTEL SW0011 Crewel Tan PASTEL SW0012 Empire Gold PASTEL SW0013 Majolica Green PASTEL SW0014 Sheraton Sage PASTEL SW0015 Gallery Green DEEPTONE SW0016 Billiard Green DEEPTONE SW0017 Calico DEEPTONE SW0018 Teal Stencil DEEPTONE SW0019 Festoon Aqua PASTEL SW0020 Peacock Plume PASTEL SW0021 Queen Ann Lilac PASTEL SW0022 Patchwork Plum PASTEL SW0023 Pewter Tankard PASTEL SW0024 Curio Gray PASTEL SW0025 Rosedust PASTEL SW0026 Rachel Pink PASTEL SW0027 Aristocrat Peach PASTEL SW0028 Caen Stone PASTEL SW0029 Acanthus PASTEL SW0030 Colonial Yellow DEEPTONE SW0031 Dutch Tile Blue DEEPTONE SW0032 Needlepoint Navy DEEPTONE SW0033 Rembrandt Ruby DEEPTONE SW0034 Roycroft Rose DEEPTONE SW0035 Indian White PASTEL SW0036 Buckram Binding DEEPTONE SW0037 Morris Room Grey DEEPTONE SW0038 Library Pewter DEEPTONE SW0039 Portrait Tone DEEPTONE SW0040 Roycroft Adobe DEEPTONE SW0041 Dard Hunter Green DEEPTONE SW0042 Ruskin Room Green DEEPTONE SW0043 Peristyle Brass DEEPTONE SW0044 Hubbard Squash PASTEL Item Number Color Name Color Code SW0045 Antiquarian Brown DEEPTONE SW0046 White Hyacinth PASTEL SW0047 Studio Blue Green DEEPTONE SW0048 Bunglehouse Blue DEEPTONE SW0049 Silver Gray PASTEL SW0050 Classic Light Buff PASTEL SW0051 Classic Ivory PASTEL SW0052 Pearl -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

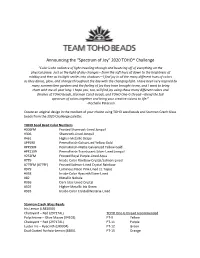

2020 TOHO® Challenge

Announcing the "Spectrum of Joy" 2020 TOHO® Challenge “Color is the radiance of light traveling through and bouncing off of everything on the physical plane. Just as the light of day changes—from the soft hues of dawn to the brightness of midday and then as twilight settles into shadows—I find joy in all the many different hues of colors as they dance, glow, and change throughout the day with the changing light. I have been very inspired by many summertime gardens and the feeling of joy they have brought to me, and I want to bring them with me all year long. I hope you, too, will find joy using these many different colors and finishes of TOHO beads, Starman Czech beads, and TOHO One-G thread—blend the full spectrum of colors together and bring your creative visions to life!” –Rochelle Peterson Create an original design in the medium of your choice using TOHO seed beads and Starman Czech Glass beads from the 2020 Challenge palette: TOHO Seed Bead Color Numbers #306FM Frosted Shamrock-Lined Jonquil #306 Shamrock-Lined Jonquil #461 Higher-Metallic Grape #PF590 PermaFinish-Galvanized Yellow Gold #PF590F PermaFinish-Matte Galvanized Yellow Gold #PF2109 PermaFinish-Translucent Silver-Lined Jonquil #252FM Frosted Royal Purple-Lined Aqua #779 Inside-Color Rainbow Crystal/Salmon-Lined #779FM (#779F) Frosted Salmon-Lined Crystal Rainbow #979 Luminous Neon Pink-Lined Lt. Topaz #958 Inside-Color Hyacinth/Siam-Lined #82 Metallic Nebula #936 Dark Lilac-Lined Crystal #507 Higher-Metallic Iris Green #935 Inside-Color Crystal/Wisteria-Lined Starman Czech Glass Beads Iris Lemon (LR81000) Chatoyant – Red (29717AL) TOHO One-G thread recommended Polychrome – Olive Mauve (94103) PT-9 Yellow Chatoyant – Red (29717AL) PT-11 Purple Luster Iris – Hyacinth (LR9004) PT-12 Green Dual Coated Fuchsia-Lemon (48001 PT-15 Orange Rules for Designers: ● You are strongly encouraged to use at least some of each color in the 2020 palette to create one eye-catching piece. -

A Viation Colors

Mohawk Group’s proprietary nylon color system has been developed to meet the precise color requirements for carpet product designers, A&D professionals, and end-use customers alike. Mohawk Group colors offer an extensive palette approaching 300 solution dyed options – and a selection of enhanced metallic lusters. Our exclusive color system has scientifically defined these colors as base options from which 160 South Industrial Blvd. www.mohawkgroup.com Calhoun, GA. 30701 limitless combinations can be blended to create infinite color possibilities in color space. Phone: 800-554-6637 Fax: 877-244-8054 This leading innovative color system supports current and future color trends and is designed Samples: 888-740-6936 to achieve carpet styling objectives for design professionals at all levels of global markets. Customer Service: 800-622-6228 Installation / Maintenance: Your Color Advantage • Discover How Mohawk Fibers Support 800-553-6045 x62347 • 100% Solution-Dyed Nylon Your Design Objectives. 1-877-3RE-CYCL • Recycled Content • Custom dye options are available with lead • Mergeable Capability time extensions. Contact your Mohawk Group Air representative for details. For samples, call 800.554.6637 or visit us at: www.mohawkair.com Iron 7-655 Blue Steel 5-820 Raw Silk 1-242 Platinum 7-656 Metallic Silver 7-421 Envy 4-631 Leather 6-1136 Metallic Copper 2-497Metallic Gold 3-371 Metallic Luster Achieve your design objectives with high-luster metallics. Aviation Colors Aviation Flamingo 2-429 Carrot 3-309 Bisque 3-237 Champagne 1-123 Palomino 6-868 -

SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS - Family Color

SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS - Family Color White/Silver Color Family Crystal Moonlight White Opal Crystal AB Comet Argent Lt Silver Shade Silver Night White/Ivory Color Family Crystal Moonlight White Opal Crystal AB Chalk White AB White Opal AB Silk AB Silk Lt Silk Lt Peach Lt Peach AB Vintage Rose Yellow Color Family Jonquil Jonquil AB Citrine Citrine AB Lt Topaz Lt Topaz AB Sunflower Sunflower AB Gold Color Family Golden Shadow Lt Colorado Topaz Lt Colorado Topaz Aurum Metallic Lt Gold Bronze Shade Dorado Rose Gold AB Sunflower Sunflower AB Topaz Topaz AB Orange Color Family SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS - Family Color Sun Sun AB Astral Pink Topaz Topaz AB Copper Fire Opal Fire Opal AB Rose Peach Padparadscha Padparadscha AB Indian Pink Indian Pink AB Hyacinth Hyacinth AB Red Color Family Fire Opal Fire Opal AB Lt Siam Lt Siam AB Indian Siam Siam Siam AB Red Magma Dark Siam Ruby Volcano Antique Pink Burgundy Pink Color Family Rose Gold Vintage Rose Lt Rose Lt Rose AB Rose Rose AB Fuchsia Fuchsia AB Ruby Volcano Antique Pink Burgundy Rose Peach Padparadscha AB Indian Pink Indian Pink AB Purple Color Family Lt Amethyst Lt Amethyst AB Vitrail Light Cyclamen Opal Lilac Shadow Amethyst Amethyst AB Provence Lavendar SWAROVSKI ELEMENTS - Family Color Tanzanite Tanzanite AB Heliotrope Purple Velvet Blue/Green Color Family Aquamarine Aquamarine AB Pacific Opal Lt Turquoise Blue Zircon Blue Zircon AB Caribbean Blue Bermuda Blue Opal Capri Blue Capri Blue AB Blue Color Family Blue Shade Air Blue Opal Lt Sapphire Lt Sapphire AB Sapphire Sapphire AB Cobalt Blue Cobalt -

Bulbs for Naturalizing

BULBS FOR NATURALIZING BOTANICAL & COMMON NAMES COMMENTS Allium, Flowering onion Plant small bulbs in sun, 4 to 6 inches apart; larger ones; 12-18 inches apart A. aflatunense, Ornamental garlic Height, 2 1/2 to 5 ft. ‘Purple Sensation’, 3 ft. tall, is a nice cultivar. A. karataviense, Turkestan onion Height, 10 in. Pale pink. A. moly, Golden garlic, lily leek Height, 18 in. Will grow in sun or shade. Yellow. A. neapolitanum, Daffodil garlic, Naples onion Height, 15 in. White with pink stamens. Blooms early spring. A. oreophilium, Ornamental garlic Height, 6 in. Fragrant, rose-colored blooms. A.sphaerocephalum, Ballhead onion, drumsticks Height, 30 in. Reddish purple. Camassia Height, 18 to 24 in. Pale blue flowers. Sun or light shade. 64 per sq. yd. Chinodoxa, Glory-of-the-snow C. lucilae Height, 5 to 8 in. Sun or light shade. 100/sq. yd. Bright blue. Colchicum autumnale, Autumn crocus, Height, 8 in. Sun or light shade. Blooms late fall. Plant 24 per sq. yd. ‘Autumn Queen’ is a light purple cultivar with dark pur- meadow saffron ple checks C. speciosum Rose to purple flowers with cultivars ranging from white to red. To 12 in. tall. Crocus, Crocus Height, 3 to 5 in. Sun. Spring blooming. Plant 144 per sq. yd . Great for naturalizing. Species lives longer than showy Dutch crocus, C. vernus. Species include C. angustifolius, C. chrysanthus, C. sieberi, C. speciosus (fall bloomer), and C. tomasinianus. Eranthis hyemalis, Winter aconite Height, 2 to 6 inches. Sun or shade. 144 per sq. yd. Yellow-gold flowers. Blooms as early as snowdrops. -

Grant E. Mitsch Daffodil Haven 1975

DAFFODIL HAVEN ' • • • I. t7:45 1C14 7 t , 401. 4ff ■• , '"-7k.i•' . 1*/*. v#1.- 4 0-4 4 41 Or FOREWORD: The years pass so rapidly that it seems one has hardly finished filling orders and replanting bulbs until it is time to prepare another catalog! As we proceed to this task, we must take the opportunity to thank all of you who have ordered from us over the past years, and to express our appreciation for the patience shown last year when some of you were disappointed in getting refunds instead of the bulbs you wanted. This was an unavoid- able circumstance necessitated by bulb iniuries sustained through an untimely freeze following an exceptionally wet period. We were prevented from billing up some of the rows as we normally do, and the shallow covering did not give adequate protection to the water saturated bulbs. We trust that in most instances we will have good bulbs of most of these cultivars this season, although a few will not be available this year. We should have more bulbs this year than last, but can never be sure of the crop. After some forty-eight years growing bulbs, we know that it is imperative that we decrease our planting this year, and it is likely that many of the things listed now are being offered by us for the last time, much as we dislike to part with some of our favorites. A number of new Daffodils are being introduced this year, among which there are some that should be capable of winning on the show bench.