Review of Pay for Performance - Overview and Key Findings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

Physicians' and Nurses' Attitudes Towards

GLOBAL HEALTH ACTION, 2017 VOL. 10, NO. 1, 1270813 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2017.1270813 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Physicians’ and nurses’ attitudes towards performance-based financial incentives in Burundi: a qualitative study in the province of Gitega Martin Rudasingwaa and Marie Rose Uwizeyeb aInstitute of Health Economics and Clinical Epidemiology, University Hospital of Cologne, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; bCompany for Research in Social, Behavior and Health, Kigali, Rwanda ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Background: Performance-based financing (PBF) was first implemented in Burundi in 2006 as Received 11 August 2016 a pilot programme in three provinces and was rolled out nationwide in 2010. PBF is a reform Accepted 5 December 2016 approach to improve the quality, quantity, and equity of health services and aims at achiev- RESPONSIBLE EDITOR ing universal health coverage. It focuses on how to best motivate health practitioners. Objective: To elicit physicians’ and nurses’ experiences and views on how PBF influenced and Ingela Krantz, Skaraborg Institute for Research and helped them in healthcare delivery. Development, Sweden Methods: A qualitative cross-sectional study was carried out among frontline health workers such as physicians and nurses. The data was gathered through individual face-to-face, in- KEYWORDS depth, semi-structured interviews with 6 physicians and 30 nurses from February to March Performance-based 2011 in three hospitals in Gitega Province. A simple framework approach and thematic financing; incentives; analysis using a combination of manual technique and MAXQDA software guided the analysis physicians; nurses; attitudes; of the interview data. Burundi Results: Overall, the interviewees felt that the PBF scheme had provided positive motivation to improve the quality of care, mainly in the structures and process of care. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Burundi Health System Support-Additional Financing (P166576) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Combined Project Information Documents / Integrated Safeguards Datasheet (PID/ISDS) Appraisal Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 01-May-2019 | Report No: PIDISDSA27011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized May 03, 2018 Page 1 of 15 The World Bank Burundi Health System Support-Additional Financing (P166576) BASIC INFORMATION OPS_TABLE_BASIC_DATA A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Project Name Parent Project ID (if any) Burundi P166576 Burundi Health System P156012 Support-Additional Financing Parent Project Name Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Health System Support Project AFRICA 01-Nov-2018 29-Mar-2019 ("KIRA") Practice Area (Lead) Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Health, Nutrition & Population Investment Project MINISTRY OF FINANCE Ministry of Health, Financing Ministry of Health, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Health Proposed Development Objective(s) Parent To increase the use of quality Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health services, and, in the event of an Eligible Crisis or Emergency, to provide immediate and effective response to said Eligible Crisis or Emergency. Components Use of Performance-based Payments to Support the Recipient's Free Health Care (FHC) Program Implementation Support for the FHC program-related activities Strengthening of Newly Integrated FHC Program Service Providers through financing of minor -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 30 March to 5 April 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 5 April 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 30 March to 5 April 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 5 April 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 6 105 100 11 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 1 251 130 Algeria 4 1 343 0 6 1 Gambia 9 0 184 10 Mauritania 14 7 20 0 14 0 39 2 Senegal 304 1 29 0Eritrea 226 2 Niger 6 251 35 Mali 7 1 Burkina Faso 41 7 1 0 Guinea Chad 1 251 0 Cabo Verdé 345 17 53 0 43 1 4 690 18 4 1 232 5 26 0 Nigeria 111 3 Côte d’Ivoire South Sudan 1 873 895 15 9 0 186 3 85 4 Guinea-Bissau Ghana 943 187 555 9 3 970 64 44 3 139 0 2 0 1 0 Central African 22 0 Liberia 214 5 21 0 1 0 Benin Cameroon 4 732 26 Ethiopia 18 0 152 5 Republic 1 618 5 14 138 83 Sierra léone Togo 352 14 2 1 1 449 71 Uganda 39 17 Democratic Republic 637 1 169 0 14 0 22 0 142 4 6 0 of Congo 15 5 202 0 Congo 45 0 Gabon 3 453 2 273 Kenya 1 0 253 1 Legend 13 3 9 0 38 0 37 0 21 1 42 143 527 Rwanda Measles Humanitarian crisis 102 0 45 5 5 930 69 Burundi 4 0 10 0 Hepatitis E Monkeypox 8 892 300 3 294 Seychelles Sao Tome 161 18 110 0 16 0 Tanzania 640 0 Yellow fever and Principe 22 1 2 0 Lassa fever 79 0 Dengue fever Equatorial Cholera Guinea Angola 1 471 18 Ebola virus disease Comoros Rift Valley Fever 4 0 131 0 2 0 Chikungunya 218 0 cVDPV2 Malawi 14 2 Zambia Mozambique Leishmaniasis 35 1- COVID-19 3 0 Plague Zimbabwe 313 13 Madagascar Anthrax Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever Namibia 286 1 Malaria 5 1 169 7 Botswana 77 0 Floods Meningitis 16 0 Mauritius Cases 7 063 59 10 0 Deaths Countries reported in the document 4 1 Non WHO African Region Eswatini N WHO Member States with no reported events W E 3 0 Lesotho9 0 1 655 11 South Africa 20 0 S South Africa Graded events † 48 15 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 40 22 20 31 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

Reproductive and Maternal and Child Health (RMCH) Advisor

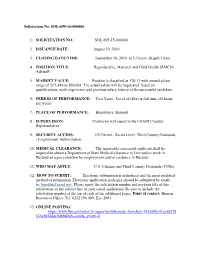

Solicitation No. SOL-695-16-000006 1. SOLICITATION NO.: SOL-695-15-000006 2. ISSUANCE DATE: August 30, 2016 3. CLOSING DATE/TIME: September 30, 2016 at 5:30 p.m. (Kigali Time) 4. POSITION TITLE: Reproductive, Maternal and Child Health (RMCH) AdvisoR 5. MARKET VALUE: Position is classified at GS-13 with annual salary range of $73,846 to $96,004. The actual salary will be negotiated based on qualifications, work experience and previous salary history of the successful candidate. 6. PERIOD OF PERFORMANCE: Two Years. Level of effort is full time (40 hours per week) 7. PLACE OF PERFORMANCE: Bujumbura, Burundi 8. SUPERVISION: Contractor will report to the USAID Country Representative 9. SECURITY ACCESS: US Citizen - Secret Level; Third Country Nationals - Employment Authorization 10. MEDICAL CLEARANCE: The apparently successful applicant shall be required to obtain a Department of State Medical clearance to Live and/or work in Burundi as a pre-condition for employment and/or residence in Burundi. 11. WHO MAY APPLY: U.S. Citizens and Third Country Nationals (TCNs) 12. HOW TO SUBMIT: Electronic submission is authorized and the most preferred method of submission. Electronic application packages should be submitted by email to: [email protected]. Please quote the solicitation number and position title of this solicitation on the subject line of your email application. Be sure to include the solicitation number at the top of each of the additional pages. Point of contact: Human Resources Office, Tel: 0252 596 400; Ext. 2605 13. ONLINE POSTING: https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=7613690c91ec5d378 635c883dd4cbd6b&tab=core&_cview=0 Please note that currently only adult dependents employed at the Embassy are authorized at post. -

Defeating Malaria Through Pharmaceutical Systems Strengthening Results from the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program

DEFEATING MALARIA THROUGH PHARMACEUTICAL SYSTEms STRENGTHENING Results from the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program Seydou Doumbia, Aubrey Clark, and Andwele Mwansasu Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the 70+ in-country staff, partners, and stakeholders who shared their insights through in-depth interviews, without which this report would not have been possible. Photos taken by Aubrey Clark (MSH/SIAPS) unless otherwise noted. ABOUT SIAPS | The Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) program works to ensure access to quality pharmaceutical products and effective pharmaceutical services through systems-strengthening approaches to achieve positive and lasting health outcomes. SIAPS is funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by Management Sciences for Health. For more information, visit www.SIAPSprogram.org. The information provided in this document does not reflect or represent the position or views of the US Agency for International Development or the US Government. ACRONYMS ACT artemisinin-based combination therapy APTS Auditable Pharmacy Transactions and Services CRMS Continuous Results Monitoring System DNPL Direction Nationale de la Pharmacie et des Laboratoires DRC Democratic Republic of the Congo DTC drug and therapeutics committee EML essential medicines list EUV End Use Verification GFATM Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria IPTp intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy LMIS logistics management information -

Impact of Social Support on Malaria Management by Burundian Community Health Workers Bonaventure Bazirutwabo Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2018 Impact of Social Support on Malaria Management by Burundian Community Health Workers Bonaventure Bazirutwabo Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Epidemiology Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Health Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Bonaventure Bazirutwabo has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Tolulope Osoba, Committee Chairperson, Public Health Faculty Dr. Xianbin Li, Committee Member, Public Health Faculty Dr. Mehdi Agha, University Reviewer, Public Health Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2018 Abstract Impact of Social Support on Malaria Management by Burundian Community Health Workers by Bonaventure Bazirutwabo MPH, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, 2005 MD, University of Burundi, 1994 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Health Walden University May 2018 Abstract Malaria is the main cause of mortality for children under the age of 5 in Burundi. The access to malaria diagnostics and treatment is hampered not only because of logistical issues, but also due to the lack of qualified human resources and their inequitable distribution across the country. -

Burundi's Health Sector

BURUNDI’S HEALTH SECTOR www.ahb.co.ke 1 2 Contents 1. Country Overview The Republic of Burundi is a landlocked country bordering Rwanda to the north, Tanzania to the 1. Country Overview 2 east, Lake Tanganyika to the southwest, and the 1.1. Key Country Statistics 2 Democratic Republic of Congo to the west. Its capital city is called Bujumbura. Burundi has a population of 2. COVID-19 3 11.6 million [1]. 3. Health Overview 3 The main communities are the Hutu and Tutsi, with 3.1. Key Health Statistics 4 the Hutu being more dominant. Inter-ethnic rivalry has affected the country since the independence 4. Challenges facing the private health sector 5 of Burundi in 1962 [1]. Burundi faced civil wars from 5. Opportunities for the private health sector 5 1993 to 2005. The Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement, also known as the Arusha Accords, 6. References 7 played a major role in ending the civil war. The negotiations of the agreement were facilitated by the late presidents Nelson Mandela and Julius Nyerere [2]. However, the political crisis in 2015 diminished the growth experienced since the signing of the agreement. The economy thrives on agriculture, accounting for 40.7% of the GDP and 80% of labour. The economic recovery strengthened in 2019 with a 3.3% growth in real GDP. Close to two- thirds of the population live below the poverty line with the youth unemployment rate at 65%. Human capital is low due to an underperforming education system and gaps between skills and labour market demand [3]. -

Population Coverage of Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

POPULATION COVERAGE OF MATERNAL, NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH INTERVENTIONS: THE IMPACT OF DONOR FINANCING, COVERAGE CHANGE METRICS AND PREDICTORS OF MATERNAL HEALTH SERVICE UTILIZATION. By Anuli N. Nwaohiri A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland December 2013 ©2013 Anuli Nwaohiri All Rights Reserved Abstract Background Donor financing in conjunction with national policies works through the existing health system to impact the uptake of MNCH interventions. However within countries, other key factors such as individual and household behaviors, the political economy, and the macroeconomic environment also influence the uptake of interventions. Demonstrating the relationship between increased financing and increased coverage can provide a platform for policymakers and other stakeholders to refine and appropriately target their health programs. Methods This complex relationship between financing and coverage was analyzed on a global level among multiple countries: 1) A multi-country analysis examining the impact of official development assistance on the change in coverage levels of MNCH interventions; 2) To further contextualize the results of the multi-country analysis, a systematic review was performed to identify the different metrics used in computing coverage change; and 3) Individual-level factors related to utilization of maternal health services was examined among women of varying socioeconomic status in Nigeria. Results The multi-country analysis examining the impact of official development assistance (ODA) on coverage levels of MNCH interventions positive associations. The systematic review found that the method of computing change is important in coverage change ii estimates; and this can impact findings and future research directions. -

Evaluating Health Care Financing Reforms in Africa

Uitnodiging Evaluating Health Care Financing Reforms in Africa Reforms Financing Care Health Evaluating Africa is experiencing steady economic growth but trends in U bent van harte uitgenodigd voor the health status of the population are lagging behind. This het bijwonen van de openbare verdediging van het proefschrift: provides an opportunity for health care financing reforms to improve equitable access to good quality health care. The aim Evaluating Health Care of this thesis is to provide evidence about the effectiveness Financing Reforms in Africa of health care financing reforms, such as health insurance door Igna Bonfrer and performance based financing, implemented in different African countries over the last decade. This evidence can help op donderdag 11 juni 2015 om policy makers to take well informed decisions about reforms 15.30u precies in de Senaatszaal necessary to achieve Universal Health Coverage by 2030. (Erasmus gebouw) van de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Campus Woudestein, Burgemeester Igna Bonfrer is currently a researcher at the institute of Health Oudlaan 50 te Rotterdam. Policy and Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam. De verdediging zal in het She will do her post-doctoral research at Harvard University, Engels zijn. funded through a NWO Rubicon fellowship. In this research she plans to evaluate the effects of Obama Care, specifically aspects related to performance based financing. Na afloop van de verdediging bent U van harte welkom op de receptie in de foyer van het Erasmus Paviljoen. Igna Bonfrer Igna -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 25: 15 - 21 June 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 21 June 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 25: 15 - 21 June 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 21 June 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 104 10 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 11 771 845 Algeria 37 2 1 0 485 0 2 813 108 Gambia 7 0 858 74 1 036 67 Mauritania 22 0 1 961 111 Senegal 304 1 143 0Eritrea 5 888 84 Niger 8 193 39 Mali 890 8 Burkina Faso 95 4 0 5 7 0 Cabo Verdé Guinea 901 53 53 0 Chad 4 532 74 5 644 14 4 1 20 244 518 29 0 Nigeria 4 998 27Côte d’Ivoire South Sudan 1 873 895 15 2 808 23 274 3 32 0 Guinea-Bissau Ghana 987 202 11 281 300 8 191 112 569 13 139 0 2 0 10 0 Central African 25 0 Liberia 7 492 54 22 0 1 882 34 Benin Cameroon Republic 4 732 26 Ethiopia 1 512 16 14 154 85 1 618 5 Sierra léone Togo 21 219 83 1 175 11 702 38 Uganda 120 18 Democratic Republic 817 3 593 3 14 0 765 13 4 738 123 of Congo 8 4 202 0 1 327 55 1 1 Congo 755 0 Gabon 3 463 2 280 682 6 Kenya 23 13 642 13 Legend 626 34 9 0 98 4 37 0 4 428 34 60 613 806 Rwanda Measles Humanitarian crisis 728 2 1 087 37 10 533 147 Burundi 698 10 11 0 Hepatitis E Monkeypox 144 1 5 826 129 Seychelles Sao Tome 113 0 Yellow fever Tanzania 857 0 70 0 Lassa fever and Principe 509 21 21 7 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera 1 702 47 1 043 12 Angola Ebola virus disease Comoros cVDPV2 Equatorial 730 11 247 5 123 0 2 0 Chikungunya Guinea 696 0 COVID-19 Malawi 176 9 Zambia Mozambique Guinea Worm 1 430 11 Anthrax Leishmaniasis Zimbabwe 2 625 21 Madagascar Malaria Namibia Floods Plague 303 1 Botswana 489 6 337 10 Cases Crimean-Congo -

SSHAP Cross Border Dynanics Burundi DRC Updated August 2019

Social Science in Humanitarian Action Skeatlivesat20A www.socialscienceinaction.org Cross border dynamics: Burundi-DRC (updated August 2019) This brief summarises key considerations concerning cross-border dynamics between Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the context of the outbreak of Ebola in North Kivu and Ituri provinces. It is the third in a series of four briefs focusing on the at risk border areas between DRC and the four high priority neighbouring countries (Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan).1 As of July 2019, there have been no cases of Ebola imported from the DRC into Burundi, although cross-border movement has been identified as a significant risk to transmission. This brief provides details about cross-border relations, the political and economic dynamics likely to influence them, and specific areas and actors most at risk. The brief is based on a rapid review of existing published and grey literature, previous ethnographic research in Burundi and informal discussions with in-country colleagues. The brief was developed by Jean-Benoît Falisse (University of Edinburgh), with support from Ingrid Gercama, Nadia Butler, Theresa Jones and Juliet Bedford (Anthrologica) and Oto-Asael Magerano, Louis Rivière, Shaka and Hugues Nkengurutse. Prior finalisation, it was reviewed by expert advisors from the University of Antwerp, University of Cambridge, Université Catholique de Louvain, University of Edinburgh, University of Gent, Université du Lac Tanganyika, Northwestern University, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, and the UNICEF Country Office in Burundi. The brief is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform (SSHAP). Key considerations and recommendations • Politicisation: The ruling party, Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie – Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (the National Council for the Defence of Democracy – Forces for the Defence of Democracy, CNDD-FDD), is present at all levels of public (and often private) life.