House of Representatives 2 State House Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Scorecard

Maine Service Employees Association, SEIU Local 1989’s Legislative Scorecard: SOMSEA 129th Maine Legislature Special See whether your state senator and state representative voted pullout for or against MSEA and workers on key issues we tracked. section! During the 2019-2020 Legislature cut short by the COVID-19 pandemic, we tracked every state legislator’s votes on key issues impacting Maine workers. To be sure, important legislation remains pending that we’d also like to score, including LD 1978 reforming the MainePERS disability process, LD 1878 establishing a career path for adjunct professors in the Maine Community College System, and LD 1355 strengthening the retirement security of workers in the State Police Crime Lab and State Police Computer Crimes Unit. Please contact your state senator and state representative today; encourage them to finish the Legislature’s business! Use this Scorecard to see whether your state senator and state representative voted for or against MSEA and workers on these key issues: • Approving the bipartisan two-year state budget (LD 1001, signed into law by Governor Mills). We supported the final budget. It addresses understaffing, funds our Judicial and Executive Branch contracts, and increases funding for Child Development Services, Governor Baxter School for the Deaf/MECDHH, and the Maine Community College System. It makes MSEA-SEIU PASER Member Frank Geagan, at right, asks his State Senator, Brad Farrin, to support investments in local schools and progress a comprehensive study of compensation for state employees in 2019 during the Maine AFL-CIO on property tax relief by increasing revenue Labor Lobby Day. Senator Farrin voted against Maine workers and MSEA on all the issues we sharing. -

Maine Legislature 2 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0002 (207) 287-1400 TTY: (207) 287-4469 April 13, 2020

Maine Legislature 2 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0002 (207) 287-1400 TTY: (207) 287-4469 April 13, 2020 Mr. Dirk Lesko President General Dynamics Bath Iron Works 700 Washington St. Bath, ME 04530 Dear Mr. Lesko: As you know, COVID-19 projections suggest we may soon be nearing our peak here in Maine. We are all urgently concerned about the impact on our state’s healthcare system, on all patients in critical need, and on our front-line healthcare workers in the battle against this virus. As state legislators from across Maine, we, the undersigned, understand the profound statewide impact of your company. With 6,800 or so workers from all 16 counties passing through your gates each day, your Bath-Brunswick complex is by far the biggest congregate worksite in our state. We recognize, too, your initial steps to protect public health. These include requiring cloth masks of workers, banning the use of private vans for commuting, donation of some of your personal protective equipment (PPE) to the health care system, frequent sanitation, purchase of meals from local restaurants, and an extension of unpaid leave options to May 8th. While these steps are helpful, we implore you to take all additional measures within your powers. We are all aware of the two confirmed COVID-19 cases at BIW, as of this writing. Some of us also have direct reports from other BIW workers who were clinically diagnosed and staying home without testing, due to necessary limits on test availability. We recall past episodes at BIW such as the tuberculosis outbreak in 1989-1990 or the 1918 flu fatalities in the BIW region, and hope to avoid a similar experience. -

VL Tammaro Fuels the Love by Delivering 1,000 Free Gallons by Lura Jackson Ticipated, Bringing Fuel to the Selves, Rosena Crossman Homes of Several Customers

Join us on Twitter @TheCalaisAdv Like us on Facebook VOL. 184, NO. 8 FEBRUARY 21, 2019 © 2019 The Calais Advertiser Inc. $1.50 (tax included) VL Tammaro Fuels the Love by Delivering 1,000 Free Gallons By Lura Jackson ticipated, bringing fuel to the selves, Rosena Crossman homes of several customers. and Andy Ramsdell, were What better way to express Each provider participating thrilled to be a part of the affection to a member of the in Fuel Your Love chooses event, Tammaro said. “It’s community than by bring- the customers to receive the been exciting for the drivers. ing them a gift that literally free deliveries based on their They love spreading good warms their home? On Val- own criteria. VL Tammaro news.” entine’s Day, drivers from VL delivered to retired nurses, an The drivers were decked Tammaro – and owner Mike EMT, widows – all of them out in bright red outfits to Tammaro himself – filled the were long-time customers accompany the truck itself tanks of eight households and those who have “done – which was similarly col- in Baileyville, Calais, and good in the community,” ored in an appropriate red Princeton as part of the annu- Tammaro said. “In some hue thanks to a large banner al Maine Energy Marketer’s cases, they really needed the provided by MEMA. The Association [MEMA] Fuel help. It’s toward the end of eye-catching scene was ap- Your Love event. More than winter and people need extra propriately completed by 1,000 gallons were delivered help at this time of year.” Tammaro gifting each recipi- at no cost. -

Senator Anne Carney, Senator Lisa Keim, Senator Heather Sanborn, R

March 11, 2021 Memo for the SUPPORT of Bill Number: LD622 To: Senator Anne Carney, Senator Lisa Keim, Senator Heather Sanborn, Representative Thom Harnett, Representative Christopher Babbidge, Representative Kathy Downes, Representative Jeffrey Evangelos, Representative David Haggan, Representative Laurel Libby, Representative Stephen Moriarty, Representative Rena Newell, Representative Jennifer Poirier, Representative Lois Reckitt, Representative Erin Sheehan I testify today as an individual citizen, business owner, disabled veteran, mother of a Down Syndrome child and as a Small Business Association (SBA) Leadership Council Representative. My testimony is simple - Washington politics are finally aligning with social justice and I implore Maine Legislature to integrate those same alignments with the implementation of LD622, the bill to end child marriage in Maine. I am from the Washington D.C. area and work tirelessly and passionately to advocate on behalf of special needs children, a forgotten niche within the most vulnerable population (yes, they, too, can be coerced into marriage). LD622 does not just protect underage children, but also protects minors who might otherwise be incapable of distinguishing subpar adult motives. You are not alone in standing up for basic human rights! The good news is that here, in Washington, underage marriage and the general plight against pedophilia, is no longer unnoticed or taboo. I have seen the great bi-partisan strides being made to end these atrocities, including support from the private sector. We need courage on both sides of the aisle, and to listen when the people speak up about issues that matter, like preventing underage marriage and protecting our children. Thank you for your time and consideration. -

December 21, 2012

August 5, 2019 Via Email Hon. Michael Carpenter Hon. Donna Bailey Co-Chairpersons Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Implementing Act Maine State Legislature Augusta, ME Dear Senate Chair Carpenter and House Chair Bailey: At the first meeting of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Implementing Act (“Task Force”) on July 22, 2019, you asked the Tribal Nations’ representatives to provide the Task Force with suggested redline revisions to the Maine Act to Implement the Indian Land Claims Settlement (“Maine Implementing Act”) to reflect changes that the Tribes would like to see. As counsel for the Penobscot Nation, the Passamaquoddy Tribe, the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, and the Aroostook Band of Micmac Indians, we are authorized to submit the attached redline revisions as you requested. We want to emphasize that these revisions are submitted to you in furtherance of the Maine Legislature’s June 10, 2019 Joint Resolution to Support the Development of Mutually Beneficial Solutions to the Conflicts Arising From the Interpretation of an Act to Implement the Maine Indian Claims Settlement and the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980 (“Joint Resolution”), which states: We, the Members of the One Hundred and Twenty-ninth Legislature now assembled in the First Regular Session, on behalf of the people we represent, take this opportunity to recognize that the Maine tribes should enjoy the same rights, privileges, powers and immunities as other federally recognized Indian tribes within the United States These revisions are also submitted to you in furtherance of the request made by House Speaker Gideon and Senate President Jackson that the Tribes’ leaders articulate the Re: Task Force to Amend Maine Implementing Act August 5, 2019 Page 2 goals that should drive the Task Force. -

130Th Legislature

2021 Legislation by Subject Topics LR Title Sponsor ACF 1511 An Act To Allow Procurement of Surplus Lines Insurance for Sen. Troy Jackson, Aroostook Commercial Forestry Construction Equipment ACF - Conveyances 1051 An Act To Place Certain Public Lands Under the Jurisdiction Sen. Brad Farrin, Somerset of the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry ACF - Forest Rangers retirement 1661 An Act To Create Equality in Retirement for Forest Rangers Rep. Donna Doore, Augusta with That of Employees of State Conservation Law Enforcement Agencies ACF - Forestry -- Fire control 918 An Act To Eliminate Online Burn Permit Fees for All Areas of Sen. Jim Dill, Pebobscot the State ACF - Forestry - Practices 544 An Act To Provide That a Forestry Operation That Conforms to Sen. Russell Black, Franklin Accepted Practices May Not Be Declared a Nuisance ACF - Forestry - Timber 1101 An Act To Explore Alternative Uses of Pulpwood and To Rep. Jack Ducharme, Madison harvesting Support the Logging and Forestry Industries ACF - Herbicides 577 An Act To Prohibit the Aerial Spraying of Glyphosate and Sen. Troy Jackson, Aroostook Other Synthetic Herbicides for the Purpose of Silviculture ACF - Herbicides 1113 An Act To Protect Children from Exposure to Toxic Chemicals Rep. Lori Gramlich, Old Orchard Beach ACF - Land Use Planning - 1365 An Act To Amend the Appointment Criteria for the Maine Rep. Maggie O'Neil, Saco Administration Land Use Planning Commission ACF - Law Enforement 661 An Act To Authorize a General Fund Bond Issue To Repair or Rep. Michelle Dunphy, Old Replace Bureau of Forestry Helicopters Town ACF - Perfluoroalkyl and 978 Resolve, Directing the Department of Agriculture, Rep. -

2019 Legislative Scorecard for the 129Th Maine Legislature

Maine State Employees Association, SEIU Local 1989’s 2019 Legislative Scorecard for the 129th Maine Legislature SOMSEA See whether your state senator and state representative voted for or against MSEA and workers on key issues we tracked. During the 2019 legislation, we tracked the votes of every state legislator on key issues impacting Maine workers. Use this Scorecard to look up whether your state senator and state representative voted for or against MSEA and workers on our issues: • Approving the bipartisan two-year state budget (LD 1001, signed into law by Governor Mills). We supported the final budget. It addresses understaffing, funds our Judicial and Executive Branch contracts, and increases funding for Child Development Services, Governor Baxter School for the Deaf/MECDHH, and the Maine Community College System. It makes investments in local schools and progress on property tax relief by increasing revenue sharing. It also strengthens the Property Tax Fairness Credit. • Strengthening workers’ rights (LD 1177, vetoed by Governor Mills). This legislation would have strengthened collective bargaining rights by making arbitration binding on key economic issues for public workers. The rights of public workers need to be strengthened to defend our families and the services we provide to the people of Maine. While we’re encouraged it passed in both the Maine House and the Maine Senate, we remain disappointed Gov. Mills vetoed it. We’ll keep fighting to strengthen collective bargaining rights. • Providing pay parity for Maine DHHS MSEA-SEIU PASER Member Frank Geagan, at right, asks his State Senator, Brad Farrin, to support caseworkers (LD 428, carried over to the January a comprehensive study of compensation for state employees March 13 during the Maine AFL- 2020 legislative session). -

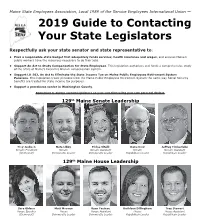

2019 Guide to Contacting Your State Legislators Using Alliance-Press Template.Indd

Maine State Employees Association, Local 1989 of the Service Employees International Union — 2019 Guide to Contacting Your State Legislators Respectfully ask your state senator and state representative to: • Pass a responsible state budget that adequately funds services, health insurance and wages, and ensures Maine’s public workers have the resources necessary to do their jobs. • Support An Act to Study Compensation for State Employees. This legislation authorizes and funds a comprehensive study of the State of Maine’s Executive Branch compensation system. • Support LD 162, An Act to Eliminate the State Income Tax on Maine Public Employees Retirement System Pensions. This legislation treats pensions from the Maine Public Employees Retirement System the same way Social Security benefi ts are treated for state income tax purposes. • Support a prerelease center in Washington County. Remember to always contact legislators on your own time using your own personal devices. 129th Maine Senate Leadership Troy Jackson Nate Libby Eloise Vitelli Dana Dow Jeff rey Timberlake Senate President Senate Senate Assistant Senate Senate Assistant (Democrat) Democratic Leader Democratic Leader Republican Leader Republican Leader 129th Maine House Leadership Sara Gideon Matt Moonen Ryan Fecteau Kathleen Dillingham Trey Stewart House Speaker House House Assistant House House Assistant (Democrat) Democratic Leader Democratic Leader Republican Leader Republican Leader Page A2 2019 Guide to Contacting Your State Legislators — Maine State Employees Association, SEIU Local 1989 129th Maine Legislature In-state toll-free message lines: Maine Senate: 1-800-423-6900 Maine House: 1-800-423-2900 *Asterisk denotes MSEA-SEIU Local 1989-endorsed in the Nov. 6, 2018, General Elections.