MURRAY–DARLING BASIN AUTHORITY Chowilla Floodplain Environmental Water Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Responses to Flooding in the Lower River Murray Following an Extended Drought

Ecological Responses to Flooding in the Lower River Murray Following an Extended Drought Synthesis Report of the Murray Flood Ecology Project Qifeng Ye, George C. Giatas, Kane T. Aldridge, Simon N. Benger, Chris M. Bice, Justin D. Brookes, Luciana B. Bucater, Katherine J. M. Cheshire, Courtney R. Cummings, Tanya M. Doody, Peter G. Fairweather, Kate A. Frahn, Josh F. Fredberg, Susan L. Gehrig, Kate L. Holland, Sandra J. Leigh, Rebecca E. Lester, Zygmunt Lorenz, Kelly B. Marsland, Jason M. Nicol, Roderick L. Oliver, Ian C. Overton, Jodie L. Pritchard, Arron D. Strawbridge, Leigh A. Thwaites, Chris J. Turnadge, Phillipa K. Wilson, Brenton P. Zampatti. Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 14/6 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science-based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. The following Associate organisation led the preparation of this report: Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder -

South Australia's National Parks Guide

SOUTH AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL PARKS GUIDE Explore some of South Australia’s most inspirational places INTRODUCTION Generations of South Australians and visitors to our State cherish memories of our national parks. From camping with family and friends in the iconic Flinders Ranges, picnicking at popular Adelaide parks such as Belair National Park or fishing and swimming along our long and winding coast, there are countless opportunities to connect with nature and discover landscapes of both natural and cultural significance. South Australia’s parks make an important contribution to the economic development of the State through nature- based tourism, recreation and biodiversity. They also contribute to the healthy lifestyles we as a community enjoy and they are cornerstones of our efforts to conserve South Australia’s native plants and animals. In recognition of the importance of our parks, the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources is enhancing experiences for visitors, such as improving park infrastructure and providing opportunities for volunteers to contribute to conservation efforts. It is important that we all continue to celebrate South Australia’s parks and recognise the contribution that people make to conservation. Helping achieve that vision is the fun part – all you need to do is visit a park and take advantage of all it has to offer. Hon lan Hunter MLC Minister for Sustainability, Environment and Conservation CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION FOR PARKS VISITORS ................11 Park categories.......................................................................11 -

The Living Murray Planned Works on the Chowilla Floodplain

Schematic diagram of the proposed Chowilla Floodplain water management structures. orth Road Wentw To Wentworth Lake Limbra Coombool Swamp SOUTH AUSTRALIA NEW SOUTH WALES LEGEND Existing Weirs Punkah Cr ee k Upgraded Weirs Coombool (outstation) Old Existing Fishways Lake Wentw Littra ort h Ro a New Fishways Werta P S d ip la ec n Wert l e a y Punkah Environmental y C r C Slaney ee k k Island Regulator k Monoman Island e d e Island oa r Bo Existing Regulators R C a th t C Isle or k tw of Man en n W a New Regulators om on Tareena M I V E R ek New Embankments R Cre Grand S alt ek Y To Renmark e r A H Junction New Channel C y R p Island a u l R l rn i Chowilla U a Chowilla Floodplain w o Island M h C Lock 6 Bridges Hypurna k ree Island C d C d a r e Ro e h o e s h k l urt o M o Chowilla W Homestead Chowilla Creek Mildura Environmental Lock 6 Regulator ADELAIDE Chowilla Island Woolshed Creek Loop Channel Eastern Regulator & Regulator MELBOURNE Woolshed Creek Southern Regulator Chowilla Island Murtho Loop Regulator M Chowilla N U Island R R E 0 2 4 0 1 2 R A I V VICTORIA Y R kilometers kilometers Lindsay Point The LivingMurray Planned works on the Chowilla Floodplain ontheChowilla Planned works Planned works on the Chowilla Floodplain About The Living Murray The floodplain environment is undergoing a severe decline The regulator incorporates fish passage for large, medium due to the reduction in the frequency of flooding from the and small-bodied native fish. -

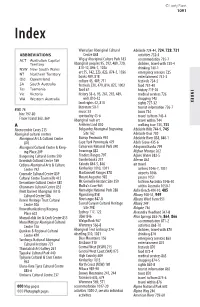

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Murray Cod (Maccullochella Peelii) Movement in the Chowilla Region of the Lower River Murray

Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii) movement in the Chowilla region of the lower River Murray J. Fredberg, B. P. Zampatti and C. M. Bice SARDI Publication No. F2019/000313-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 1035 SARDI Aquatics Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 October 2019 Fredberg, J. et al. (2019) Murray cod Movement in Chowilla Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii) movement in the Chowilla region of the lower River Murray J. Fredberg, B. P. Zampatti and C. M. Bice SARDI Publication No. F2019/000313-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 1035 October 2019 ii Fredberg, J. et al. (2019) Murray cod Movement in Chowilla This publication may be cited as: Fredberg, J., Zampatti, B.P. and Bice, C.M. (2019). Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii) movement in the Chowilla region of the lower River Murray. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication F2019/000313-1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 1035. 27pp. South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5415 http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/research DISCLAIMER SARDI Aquatic Sciences and the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR), do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for you particular purposes and therefore disclaim all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. The contents of this publication do not purport to represent the position of the Commonwealth of Australia or the MDBA in any way and, as appropriate, are presented for the purpose of informing and stimulating discussion for improved management of the Basin's natural resources. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Murray River

Murray River Follow the course of the mighty Murray River past sandstone cliffs and river red gums through mallee country and wetlands awash with native wildlife and vegetation. Murray River (photo credit: SATC). Map images: Bill Doyle and Ty Mickan. Loch Luna GR and Moorook GR Fish, canoe and walk tranquil lagoons, floodplains and wetlands. Danggali WA Spencer Gulf WALES SOUTH NEW Danggali CP Burra Chowilla Clare RR Morgan CP Chowilla GR Morgan Paddle along peaceful y waterways for rare ra Port Wakefield r Waikerie glimpses of protected Mu Renmark Barmera Australian bird life. Moorook Berri Blanchetown Loxton Sedan Swan Reach Paruna Murray River NP Purnong Gulf er Alawoona Sleep under the Riv St. Vincent ADELAIDE stars at Katarapko Mannum by the banks of the Murray River. Murray Bridge Karoonda Lyrup Flats Explore a wonderful Tailem Bend Karte CP network of creeks Pinnaroo and backwaters in Murray River National Lameroo Park’s 2000 hectareVictor Ha rbor Border Track floodplain. 4WD the legendary Border Track Meningie Coonalpyn Penneshaw through Ngarkat Conservation Park. Tintinara VICTORIA Keith Bordertown Ngarkat CP Enjoy the solitude To and beauty of vast Melbourne mallee landscapes. 68 MURRAY RIVER Chowilla Danggali Conservation Game Reserve and Park and Wilderness Regional Reserve 93,397ha Protection Area 251,232ha Danggali Conservation Park and Wilderness Protection Area became Australia’s first Follow secluded walking trails through Biosphere Reserve in 1977 and is famous great stands of river red gum and hardy for its vastness and wilderness appeal. black box and you’ll discover why Chowilla Game Reserve and Regional Many species of semi-arid land birds Reserve is an integral part of the Riverland live within its borders, offering great Biosphere Reserve. -

Riverland Visitation Snapshot

Riverland National parks visitation snapshot The region The opportunity South Australia’s Riverland region centres on the majestic Murray River and expands across the surrounding land where orchards, The Riverland’s regional strategy is to grow events, vineyards and sunny days abound. create new visitor experiences, increase business collaboration and support operators with the aim Located three hours north-east of Adelaide and running through to to increase visitation and length of stay from the Victorian border, the region is known for its spectacular cliffs Adelaide as well as key interstate markets. and red gum forests. More than 100 years ago, paddle steamers used to venture up and down the length of the river, transporting agricultural produce to and from riverside townships. These days, it’s the perfect place to float along the river in a kayak, spend time birdwatching in a national park, or embark on an unforgettable camping trip. Tourism In 2018, the Riverland region contributed $176 million to SA’s $6.8 billion tourism expenditure. The region attracts approximately 392,000 overnight visitors per year (2016-18), with 51 per cent of these from Adelaide and 26 per cent from regional SA. The Riverland has 14 visitor accommodation options*, totalling 502 available rooms. Over the course of a year, occupancy rates average at 44 per cent, peaking in April, May and October where occupancy rates are at 49 per cent. Lowest occupancy is in the winter months, dropping to 43 per cent. For more in-depth analysis, view the SA Tourism Commission regional profiles. *Hotels, motels and serviced apartments with 15+ rooms. -

Chowilla Floodplain Icon Site

Chowilla Floodplain Icon Site Summary of 2016 Environmental Water Operations and High Flows Chowilla Environmental Regulator Operation Successful high level testing of the Chowilla regulator and ancillary structures was undertaken between August and November 2016. The operation resulted in the managed inundation of approximately 7,650 hectares of floodplain and wetlands (Fig 1), providing significant benefit to floodplain vegetation and fauna including many species of frogs, birds, fish and invertebrates. The testing of the Chowilla regulator reached a target operating height of 19.75 m AHD (3.45m above normal level) in late September 2016. At the western end of the floodplain this height is equivalent to the water levels in Chowilla Creek that would occur during natural flows of around 80,000 - 90,000 ML/day flow in the River Murray. The inundation filled all of the major high elevation wetlands including Coombool Swamp, Lake Littra, Werta Wert and Gum Flat and large areas of river red gum and black box woodland and shrubland vegetation. Fig 1. Landsat 8 image captured 28/09/16 showing 7,650 ha inundated during the testing event Fig 2. Floodplain Inundation around Chowilla Creek Bridge and Lock 6 road 27 Sept. Photo: SA Water Fig 2. Floodplain Inundation around Chowilla Creek Bridge and Lock 6 road 27 Sept. Photo: SA Water Monitoring during the operation The area inundated during the testing event included significant areas that had not been flooded since the natural high flow event in 2010/11. Large areas of black box and river red gum woodlands received a much needed watering. -

Fact Sheet 2 Access to Chowilla Game Reserve During Operation of the Regulator in 2016

FACT SHEET 2 ACCESS TO CHOWILLA GAME RESERVE DURING OPERATION OF THE REGULATOR IN 2016 BACKGROUND Chowilla Game Reserve comprises floodplain and wetland environments. Chowilla features great stands of majestic river red gum and hardy black box gums, as well as Lignum and River Cooba. Large numbers of waterbirds and other native fauna can also be seen. Because of its unique ecological and cultural character the Chowilla floodplain is recognised as one of six icon sites in the Murray-Darling Basin and is listed as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention. The Chowilla floodplain has experienced severe ecological decline due to lack of flooding over long periods. This decline accelerated during the extreme drought of 2006-10, resulting in the widespread loss of mature river red gums and black box trees. What has been constructed at Chowilla? A number of important environmental works have been constructed on the Chowilla floodplain to enable use of environmental water to improve the health of the floodplain. The works include construction of an environmental regulator across Chowilla Creek downstream of Monoman Island designed to raise water levels to enable the inundation of large areas of the floodplain and wetlands. The regulator consists of a series of concrete piers and a deck. When the regulator is being operated, removable concrete stop logs (similar to those in existing River Murray weirs) are inserted between the piers to raise the water level in Chowilla Creek. During operation continuous flows are maintained over the regulator and downstream water levels will remain as normal. When the stop logs are removed, uninterrupted flow occur through the piers with no impact on water levels in Chowilla Creek. -

The South Australian Government Gazette

No. 10 769 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 18 FEBRUARY 2010 CONTENTS Page Page Adelaide Park Lands Act 2005—Notice....................................771 Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000—Notice.............. 788 Appointments, Resignations, Etc...............................................770 Proclamations ............................................................................ 816 Corporations and District Councils—Notices............................863 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................... 864 Crown Lands Act 1929—Notice ...............................................771 REGULATIONS Development Act 1993—Notices..............................................771 Development Act 1993 (No. 18 of 2010) .............................. 846 Environment Protection (Waste to Resources) Notice 2010......795 Crown Land Management Act 2009 (No. 19 of 2010) .......... 848 Environment Protection (Waste to Resources) Liquor Licensing Act 1997— Policy 2010—Notice..............................................................796 (No. 20 of 2010)................................................................. 851 Equal Opportunity Tribunal—Notice ........................................771 (No. 21 of 2010)................................................................. 853 Fisheries Management Act 2007—Notices ...............................776 -

Land Use and Tenure Chapter 9 Land Use and Tenure

EIS Volume 1 Chapter 9 Land Use and Tenure Chapter 9 Land Use and Tenure Contents 9. Land Use and Tenure ............................................................................................. 9-1 9.1. Key Findings ..................................................................................................................... 9-1 9.2. Setting the Context .......................................................................................................... 9-1 9.2.1. EIS Guidelines ...................................................................................................... 9-2 9.2.2. Requirements in legislation and other standards ............................................... 9-3 9.2.3. Views of stakeholders ......................................................................................... 9-3 9.2.4. Assessment method ............................................................................................ 9-4 9.3. Description of Existing Environment ............................................................................... 9-4 9.3.1. Land uses in the Project region ........................................................................... 9-5 9.3.2. Land uses on the transmission line corridor ....................................................... 9-3 9.3.3. Land tenure ....................................................................................................... 9-16 9.3.4. Native title and agreements with traditional owners ....................................... 9-20 9.3.5. Acquisition