TALKING to GOD, UNDER TERRENCE MALICK's TREE of LIFE João De Mancelos1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kvarterakademisk

kvarter Volume 18. Spring 2019 • on the web akademiskacademic quarter From Wander to Wonder Walking – and “Walking-With” – in Terrence Malick’s Contemplative Cinema Martin P. Rossouw has recently been appointed as Head of the Department Art History and Image Studies – University of the Free State, South Africa – where he lectures in the Programme in Film and Visual Media. His latest publications appear in Short Film Studies, Image & Text, and New Review of Film and Television Studies. Abstract This essay considers the prominent role of acts and gestures of walking – a persistent, though critically neglected motif – in Terrence Malick’s cinema. In recognition of many intimate connections between walking and contemplation, I argue that Malick’s particular staging of walking characters, always in harmony with the camera’s own “walks”, comprises a key source for the “contemplative” effects that especially philo- sophical commentators like to attribute to his style. Achieving such effects, however, requires that viewers be sufficiently- en gaged by the walking presented on-screen. Accordingly, Mal- ick’s films do not fixate on single, extended episodes of walk- ing, as one would find in Slow Cinema. They instead strive to enact an experience of walking that induces in viewers a par- ticular sense of “walking-with”. In this regard, I examine Mal- ick’s continual reliance on two strategies: (a) Steadicam fol- lowing-shots of wandering figures, which involve viewers in their motion of walking; and (b) a strict avoidance of long takes in favor of cadenced montage, which invites viewers into a reflective rhythm of walking. Volume 18 41 From Wander to Wonder kvarter Martin P. -

Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Selmin Kara Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13476 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kara, Selmin: Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions. In: Shane Denson, Julia Leyda (Hg.): Post-Cinema. Theorizing 21st-Century Film. Falmer: REFRAME Books 2016, S. 750– 784. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13476. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 6.2 Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions BY SELMIN KARA Alfonso Cuarón’s sci-fi thriller Gravity (2013) introduced to the big screen a quintessentially 21st-century villain: space debris. The spectacle of high- velocity 3D detritus raging past terror-struck, puny-looking astronauts stranded in space turned the Earth’s orbit into not only a site of horror but also a wasteland of hyperobjects,[1] with discarded electronics and satellite parts threatening everything that lies in the path of their ballistic whirl (see Figure 1). While the film made no environmental commentary on the long-term effect of space debris on communication systems or the broader ecological problem of long-lasting waste materials, it nevertheless projected a harrowing vision of technological breakdown, which found a thrilling articulation in the projectile aesthetics of stereoscopic cinema. -

Gus Van Sant Retrospective Carte B

30.06 — 26.08.2018 English Exhibition An exhibition produced by Gus Van Sant 22.06 — 16.09.2018 Galleries A CONVERSATION LA TERRAZA D and E WITH GUS VAN SANT MAGNÉTICA CARTE BLANCHE PREVIEW OF For Gus Van Sant GUS VAN SANT’S LATEST FILM In the months of July and August, the Terrace of La Casa Encendida will once again transform into La Terraza Magnética. This year the programme will have an early start on Saturday, 30 June, with a double session to kick off the film cycle Carte Blanche for Gus Van Sant, a survey of the films that have most influenced the American director’s creative output, selected by Van Sant himself filmoteca espaÑola: for the exhibition. With this Carte Blanche, the director plunges us into his pecu- GUS VAN SANT liar world through his cinematographic and musical influences. The drowsy, sometimes melancholy, experimental and psychedelic atmospheres of his films will inspire an eclectic soundtrack RETROSPECTIVE that will fill with sound the sunsets at La Terraza Magnética. La Casa Encendida Opening hours facebook.com/lacasaencendida Ronda de Valencia, 2 Tuesday to Sunday twitter.com/lacasaencendida 28012 Madrid from 10 am to 10 pm. instagram.com/lacasaencendida T 902 430 322 The exhibition spaces youtube.com/lacasaencendida close at 9:45 pm vimeo.com/lacasaencendida blog.lacasaencendida.es lacasaencendida.es With the collaboration of Cervezas Alhambra “When I shoot my films, the tension between the story and abstraction is essential. Because I learned cinema through films made by painters. Through their way of reworking cinema and not sticking to the traditional rules that govern it. -

Production Designer Jack Fisk to Be the Focus of a Fifteen-Film ‘See It Big!’ Retrospective

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRODUCTION DESIGNER JACK FISK TO BE THE FOCUS OF A FIFTEEN-FILM ‘SEE IT BIG!’ RETROSPECTIVE Series will include Fisk’s collaborations with Terrence Malick, Brian De Palma, Paul Thomas Anderson, and more March 11–April 1, 2016 at Museum of the Moving Image Astoria, Queens, New York, March 1, 2016—Since the early 1970s, Jack Fisk has been a secret weapon for some of America’s most celebrated auteurs, having served as production designer (and earlier, as art director) on all of Terrence Malick’s films, and with memorable collaborations with David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Brian De Palma. Nominated for a second Academy Award for The Revenant, and with the release of Malick’s new film Knight of Cups, Museum of the Moving Image will celebrate the artistry of Jack Fisk, master of the immersive 360-degree set, with a fifteen-film retrospective. The screening series See It Big! Jack Fisk runs March 11 through April 1, 2016, and includes all of Fisk’s films with the directors mentioned above: all of Malick’s features, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and The Straight Story, De Palma’s Carrie and Phantom of the Paradise, and Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. The Museum will also show early B- movie fantasias Messiah of Evil and Darktown Strutters, Stanley Donen’s arch- affectionate retro musical Movie Movie, and Fisk’s directorial debut, Raggedy Man (starring Sissy Spacek, Fisk’s partner since they met on the set of Badlands in 1973). Most titles will be shown in 35mm. See below for schedule and descriptions. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Lecture 2 1970S Hollywood.Pdf

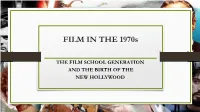

FILM IN THE 1970s THE FILM SCHOOL GENERATION AND THE BIRTH OF THE NEW HOLLYWOOD ROGER CORMAN - Born in 1926 - Known as “King of the Bs” – his best-known film is The Little Shop of Horrors (1962) - Made many low-budget exploitation films, and used the profits to finance and distribute prestigious films – many of them directed by his protégés, who went on to become some of the most influential directors of the 1970s and beyond - Honorary Academy Award in 2009 “for his rich engendering of films and filmmakers” PETER BOGDANOVICH - Born in 1939 - Film programmer at MoMA, wrote about film for Esquire; worked with Orson Welles, John Ford, and other classic Hollywood directors - 1971 – directed The Last Picture Show – followed up with successes What’s Up, Doc?, Paper Moon - Later films didn’t fulfill his early promise, but he continues to be an influential voice on the subject of film history FRANCIS - Born in 1939 FORD - MFA from UCLA (1966) – first major COPPOLA director to graduate from a prominent university film program - Screenwriter – Patton – won first Oscar - 1969 – established American Zoetrope with his protégé George Lucas - 1972 – The Godfather - 1974 – The Godfather Part 2 and The Conversation MARTIN SCORSESE - Born in 1942 - B.S. (1964) and M.A. (1968) from NYU - Worked with Corman; and, as his student project, edited Woodstock (1970) - Rose to fame in 1973 – Mean Streets – not a commercial hit, but had a dynamic style, and set a template for character types and themes and settings he would return to throughout his career GEORGE LUCAS - Born in 1944 - USC graduate – won 1965 National Student Film Festival with THX-1138 - Apprenticed with Coppola, and later collaborated with him - First major success – American Graffiti (1973) - Invested those profits into Lucasfilm, Ltd. -

Art & the Good Life

Art & the Good Life Honors Forum Spring 2021 Friday, January 22 Jon Reimer – Interview: Faith Seeking Understanding All Cohorts Zoom Friday, January 29 Kendall Cox – Art & the Good Life Juniors, Seniors McInnis Friday, February 5 Claire Holley (singer/songwriter) – Concert Freshmen, Sophomores Zoom Friday, February 12 Chris Yates – What’s at Work in the Work of Art? Juniors, Seniors Zoom Friday, February 19 Greg Thompson – Voices Underground: Public Art and Sophomores, Juniors McInnis Racial Justice Friday, February 26 Film: The Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? Freshmen, Seniors McInnis Friday, March 5 Film: Jonathan Sobol’s The Art of the Steal Sophomores, Juniors McInnis **“Beauty & the Arts” Students Friday, March 12 Caren Lambert – Beauty in Flannery O’Connor Freshmen, Sophomores McInnis Film: Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire @ 8:00pm All Welcome McInnis **“Beauty & the Arts” Students Friday, March 19 Euhri Jones – Nature, the Mural, and the Public Freshmen, Juniors McInnis Friday, March 26 Bruce Herman – An Artist’s Odyssey Sophomores, Seniors Zoom Friday, April 2 Film: Gabriel Axel’s Babette’s Feast @ 8:00pm All Welcome McInnis Friday, April 9 Suzanne Wolfe – Readings and Reflections from The Freshmen, Seniors Zoom Confession of X Saturday, April 10 Film: Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line @ 8:00pm All Welcome McInnis Friday, April 16 Chris Yates – How Films Philosophize Freshmen, Sophomores McInnis Friday, April 23 Lois Abdelmalek – Arts in Action Juniors & Seniors McInnis Friday, April 30 TBD All Welcome McInnis Nota Bene: The listed cohorts are mandatory attendees whether in McInnis or via Zoom. Cohorts that are not listed for a certain forum are strongly encouraged to attend via Zoom. -

Orange, Official Partner of the 72Nd Cannes Film Festival

Press release Paris, 2 May 2019 Orange, official partner of the 72nd Cannes Film Festival As an official partner of the Cannes Film Festival for more than 25 years, Orange is on the red carpet again this year to bring all the emotions of Cannes to life 24/7 through an exceptional programme of activities. From films in the official selection to co-producing Festival TV, co-publishing the official app, and exclusive Cannes content on Orange VoD and OCS, the whole Group is getting behind the festival. Three Orange films in the official selection This year, as every year, Orange will be presenting films at Cannes including: One feature film co-produced by Orange Studio in the Competition category: - A Hidden Life, Terrence Malick One HBO feature film distributed in a few months on OCS in the Special Screenings category: - Share, Pippa Bianco One feature film co-produced by Orange Studio in the Out of Competition category: - La Belle Époque, Nicolas Bedos. In addition, the film Deerskin by Quentin Dupieux with Jean Dujardin pre-purchased by OCS will open the Directors’ Fortnight. As part of the Cannes XR event (the world’s leading film market), the virtual reality film Alone will be presented, which is part of the Missions (OCS Signature) universe, co-produced by Orange and produced by Empreinte Digitale, which also produces the series. All the latest news from the Croisette will be broadcast live through the official Festival TV and Cannes Film Festival app Orange co-produces Festival TV alongside Canal+ and the Cannes Film Festival. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Talking to God, Under Terrence Malick's Tree of Life1

Talking to God, under Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life1 João de Mancelos (Universidade da Beira Interior) “Film is language that bypasses the mind and speaks directly to the heart”. Michelangelo Antonioni Palavras-chave: A Árvore da Vida, Deus, fé, símbolo, cinema experimental Keywords: The Tree of Life, God, faith, symbol, experimental cinema 1. The meaning of life explained in one hundred and thirty nine minutes Any movie that is simultaneously booed and applauded by an audience composed of fans and demanding critics interests me. Such was the case of The Tree of Life, written and directed by Terrence Malick, when it premiered at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival (Smith 15). A contradictory reaction usually means that the movie, regardless its quality, presents something new and possibly disturbing. In an industry flooded by commercial productions, The Tree of Life comes as a surprise, innovating both in technical and narrative terms: for instances, unusual camera angles, showing the world from the point of view of children; special effects recreating the formation of the universe, planet Earth and life; the non-linear narrative, which constantly alternates between reminiscences of the main character’s adolescence and his present life as a disenchanted adult; or the gathering of the living and the dead, wandering on a beach, on the shores of time. This freshness is not gratuitous nor does it sacrifice the plot; instead, it reveals its philosophy and symbolism, and was carefully crafted along several decades. After a period of procrastination, the shooting of The Tree of Life began in 2008. When, in an interview granted to Empire Magazine, in 2009, the specialist in visual effects Mike Fink let slip that Malick was working on an ambitious project (O’Hara), nobody could predict the magnitude of his undertaking. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

International & Festivals

COMPANY CV – INTERNATIONAL & FESTIVALS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGNS / JUNKETS / TOURS (selected) Below we list the key elements of the international campaigns we have handled, but our work often also involves working closely with the local distributors and the film-makers and their representatives to ensure that all publicity opportunities are maximised. We have set up face-to-face and telephone interviews for actors and film-makers, working around their schedules to ensure that the key territories in particular are given as much access as possible, highlighting syndication opportunities, supplying information on special photography, incorporating international press into UK schedules that we are running, and looking at creative ways of scheduling press. THE AFTERMATH / James Kent / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support COLETTE / Wash Westmoreland / HanWay Films • International campaign BEAUTIFUL BOY / Felix van Groeningen / FilmNation • International campaign THE FAVOURITE / Yorgos Lanthimos / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support SUSPIRIA / Luca Guadagnino / Amazon Studios • International campaign LIFE ITSELF / Dan Fogelman / FilmNation • International campaign DISOBEDIENCE / Sebastián Lelio / FilmNation • International campaign THE CHILDREN ACT / Richard Eyre / FilmNation • International campaign DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT / Gus Van Sant / Amazon Studios & FilmNation • International campaign ISLE OF DOGS / Wes Anderson / Fox Searchlight • International campaign THREE BILLBOARDS OUTSIDE EBBING, MISSOURI /