Socio-Economic Case for Improvements to the N16/A4 Sligo to Ballygawley and N2/A5 Monaghan to Letterkenny Transport Corridors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leitrim Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Acorn Wood Drumshanbo Road Leitrim Village Leitrim Acres Cove Carrick Road (Drumhalwy TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Aigean Croith Duncarbry Tullaghan Leitrim Allenbrook R208 Drumshanbo Leitrim 597522 810404 Bothar Tighernan Attirory Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim Bramble Hill Grovehill Mohill Leitrim Carraig Ard Lisnagat Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim 593955 800956 Carraig Breac Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Canal View Leitrim Village Leitrim 595793 804983 Cluain Oir Leitrim TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Cnoc An Iuir Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Cois Locha Calloughs Carrigallen Leitrim Cnoc Na Ri Mullaghnameely Fenagh Leitrim Corr A Bhile R280 Manorhamilton Road Killargue Leitrim 586279 831376 Corr Bui Ballinamore Road Aughnasheelin Leitrim Crannog Keshcarrigan TD Keshcarrigan Leitrim Cul Na Sraide Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Dun Carraig Ceibh Tullylannan TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Dun Na Bo Willowfield Road Ballinamore Leitrim Gleann Dara Tully Ballinamore Leitrim Glen Eoin N16 Enniskillen Road Manorhamilton Leitrim 589021 839300 Holland Drive Skreeny Manorhamilton Leitrim Lough Melvin Forest Park Kinlough TD Kinlough Leitrim Mac Oisin Place Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Mill View Park Mullyaster Newtowngore Leitrim Mountain View Drumshanbo Leitrim Oak Meadows Drumsna TD Drumsna Leitrim Oakfield Manor R280 Kinlough Leitrim 581272 855894 Plan Ref P00/631 Main Street Ballinamore Leitrim 612925 811602 Plan Ref P00/678 Derryhallagh TD Drumshanbo -

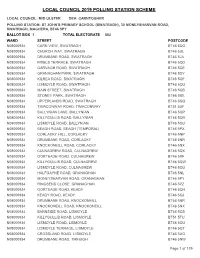

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER POLLING STATION: ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 882 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QG N08000934CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH BT46 5UL N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5JA N08000934FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH BT46 5QD N08000934GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QE N08000934GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5DY N08000934KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QF N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH BT46 5QB N08000934STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH BT46 5BE N08000934UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH BT46 5QQ N08000934TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY BT51 5UF N08000934BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QP N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QR N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN BT46 5QU N08000934BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL) BT46 5PX N08000934CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY BT46 5NP N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY BT46 5NX N08000934CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QX N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5RF N08000934KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QW N08000934LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW BT46 5QU N08000934HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5NL N08000934MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PY N08000934RINGSEND CLOSE, GRANAGHAN BT46 5PZ N08000934GORTEADE ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QH N08000934KEADY ROAD, KEADY BT46 5QJ N08000934DRUMBANE ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NR N08000934KNOCKONEILL ROAD, KNOCKONEILL BT46 5NX N08000934BARNSIDE ROAD, LISMOYLE -

Development Savills.Ie

Development savills.ie Expressions of Interest Former N2 Road, Kilshane, Co. Dublin 13.47 hectares (33.28 acres) approximately FINGLAS M50 DUBLIN AIRPORT ROADSTONE LOGISTICS PARK The Subject Property N2/M2 For identification purposes only • Strategic location fronting on to former N2, adjacent M2 Motorway and within easy reach of M50 Motorway. • Level parcel of lands comprising 14.07 Hectares (34.77 Acres) approx. which has been partially developed with roads and services. • These lands have a positive planning history for a Recycling and Waste Management Facility. A Section 175 Development Consent was granted to Fingal County Council by An Bord Pleanala and the Environmental Protection Agency has issued a Waste Licence. Savills Ireland 32 Molesworth Street, Dublin 2 Jonathan Preston (01 618 1445) [email protected] Jill Horan (01 618 1350) [email protected] +353 (0) 1 618 1300 Robert Coakley (01 618 1411) [email protected] Dublin Airport Finglas Dublin Airport Logistics Park M50 Roadstone The Subject Property N2/M2 Approximate outline only Location Zoning This land bank is strategically located at the junction of the Under the Fingal Development Plan 2011-2017, the property former N2/M2 Motorway, the lands are within easy reach is zoned Objective “HI” Heavy Industry. The purpose of this of the M50 Motorway (Junction 5) providing easy access zoning is to facilitate opportunities for industrial uses, activity to Motorway network, Dublin Airport, Dublin City and and processes which may give rise to land use conflict other Tunnel. Nearby large commercial users include Roadstone’s zonings. “HI” zoned areas provide suitable and accessible Huntstown complex and the nearby Dublin Airport Logistics locations specifically for heavy industry and shall be reserved Park, where DHL and Easons have distribution centres. -

309/R309405.Pdf, .PDF Format 246KB

Inspector’s Report ABP-309405-21 Development Construction of a 30 metre lattice tower enclosed within a 2.4 metre high palisade fence compound. Location Corgullion Townland, Carrick on Shannon, Co Roscommon. Planning Authority Roscommon County Council Planning Authority Reg. Ref. PD/20/473 Applicant(s) Cignal Infrastructure Limited Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse Type of Appeal First-Party Appellant(s) Cignal Infrastructure Limited Observer(s) None Date of Site Inspection 13th April 2021 Inspector Stephen Ward ABP-309405-21 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 19 1.0 Site Location and Description The appeal site is located is the rural townland of Corgullion, Co. Roscommon, at a distance of c. 4km southeast of Carrick-On-Shannon and c. 4km southwest of Drumsna. The Sligo – Dublin Railway line runs east to west at c. 100m to the north of the site. Further north of this is the River Shannon, which forms part of the Leitrim – Roscommon county border. The Flagford – Arva – Louth 220kv power lines also sun in an east-west direction at a distance of c. 250 metres south of the site. The wider surrounding area is otherwise characterised by undulating agricultural land interspersed by one-off houses. The site comprises a relatively flat linear section which is to be annexed along the northern boundary of a larger agricultural holding. It has a stated area of 1,104m2, with an overall length of c. 310m and a width of 3m for the vast majority of that length. The northern and western site boundaries adjoin the existing field boundaries, which are comprised of trees and hedgerows. -

Everyone Has a Place

Benefits of Radius About us Accommodation Radius Housing provides housing, care and support to over 33,000 homes. • Independence • Maintenance and repairs taken care of We are a social enterprise employing • Affordable heating and water charges over 1,100 people and managing 12,500 properties in 80 towns across Northern • Close to shops, restaurants and other Ireland. amenities Apartments for • Car parking and transport links Services include: Older People • On-site co-ordinator • Family Housing • Apartments for Older People • 24 hour emergency assistance • 24 Hour Dementia Support Co. Fermanagh & • Social activities and outings • Supported Housing • Daycare Co. Tyrone • TeleCare • Staying Put Home Adaption • Floating Support Contact “I like the guest room system Radius Housing as it means my family can Radius House 38 – 52 Lisburn Road come to visit – a big plus. The Belfast BT9 6AA scheme is very clean, safe and secure and there is a great t: 0330 123 0888 e: [email protected] atmosphere of support, a w: radiushousing.org feeling of community, care and wellbeing.” @RadiusHousing /RadiusHousing Dr Donald Kintner radiushousing Inis Fold © Radius Housing, April 2018 Registered Office: Radius Housing Association, 38 – 52 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA Registered in Northern Ireland (No. IP169), VAT Reg. Everyone No. 7917938 74 Registered with the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland NIC102575 Regulated by the Department for Communities in Northern Ireland has a place At Radius, we want you to Derg Fold Co. Fermanagh Lower Strabane Roada enjoy living independently Brownhill Fold Castlederg in our quality apartments Scallen Road Co Tyrone or bungalows specifically Irvinestown BT81 7AJ Co Fermanagh designed for people over the t: 028 8167 0707 age of 55. -

Wrap U P in Culture

WHAT ARE YOU LEITRIM N I DOING ON 2019 CULTURE NIGHT? Manorhamilton P Glenfarne Dromahair U On the evening of Friday September 20th, Leitrim comes alive with events across the county. So start planning your evening now – and remember, everything is free! For nationwide events see: www. culturenight.ie CULTURE WRAP Ballinamore Carrigallen Carrick on Shannon Mohill Drumsna Leitrim County Council Arts Office Carrick on Shannon Co. Leitrim 071 96 21694 [email protected] www.leitrimarts.ie Culture Night is brought to you by the Department of Culture, Heritage & the Gaeltacht and the Creative Ireland Programme in partnership with Leitrim County Council. An Roinn Ealaíon, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta a dhéanann comhordú ar an FRI Oíche Chultúir, i gcomhpháirt le Comhairle Contae Liatroma. 20 SEP CULTURENIGHT.IE WWW. LEITRIMARTS.IE LEITRIM 2019 BALLINAMORE MUSICAL PERFORMANCE LEITRIM DESIGN HOUSE THE OLIVE TREE CAFÉ CARRIGALLEN DROMAHAIR MANORHAMILTON LSC GALLERY: TRACES - MAPPING With Rhona Trench (Silver flute), Carole Coleman MEMORY & PLACE IN MANORHAMILTON (Irish flute), Edel Rowley (Silver Flute), Alla Crosbie, 6.30PM – 7.15PM SOLAS GALLERY (Piano/singer) Enda Stenson (Bodhrán). HOMEMADE PAINT WORKSHOP AN EVENING OF LIVE MUSIC & SONG CORN MILL THEATRE ‘I will arise and go now and go to IONAD NA nGLEANNTA / FOR ALL AGES! 4PM-5.30PM 7PM – 8.30PM Inisfree…’ Artist Sandra Corrigan-Breathnach performance DEPARTING FROM PARKE’S CASTLE 7.30PM THE GLENS CENTRE CULTURE NIGHT@ SOLAS GALLERY CREATIVE EYE PHONE WORKSHOP THIS IS YOUR THEATRE: CELEBRATING & exhibition in collaboration with The Womens WITH ANNA LEASK Kate Murtagh Sheridan will encourage participants Curated by alt folk duo ‘The Shrine of St Lachtain’s Centre; The Kilgar Group; the 24/7 Carers Group; 7.30PM – 10PM to be creative by teaching them to make and use Arm’ with special guest Colin Beggan. -

(HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children's Social Work

Northern Ireland Health and Social Care (HSC) Trusts Gateway Services for Children’s Social Work Belfast HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 028 90507000 Areas Greater Belfast area Further Contact Details Greater Belfast Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) 110 Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 6HD Website http://www.belfasttrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) South Eastern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001000300 Areas Lisburn, Dunmurry, Moira, Hillsborough, Bangor, Newtownards, Ards Peninsula, Comber, Downpatrick, Newcastle and Ballynahinch Further Contact Details Greater Lisburn Gateway North Down Gateway Team Down Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Team James Street Children’s Services Stewartstown Road Health Newtownards, BT23 4EP 81 Market Street Centre Tel: 028 91818518 Downpatrick, BT30 6LZ 212 Stewartstown Road Fax: 028 90564830 Tel: 028 44613511 Dunmurry Fax: 028 44615734 Belfast, BT17 0FG Tel: 028 90602705 Fax: 028 90629827 Website http://www.setrust.hscni.net/ Out of Hours Emergency 028 90565444 Service (after 5pm each evening at weekends, and public/bank holidays) Northern HSC Trust Telephone (for referral) 03001234333 Areas Antrim, Carrickfergus, Newtownabbey, Larne, Ballymena, Cookstown, Magherafelt, Ballycastle, Ballymoney, Portrush and Coleraine Further Contact Details Central Gateway Team South Eastern Gateway Team Northern Gateway Team (for ongoing professional liaison) Unit 5A, Toome Business The Beeches Coleraine -

GROUP / ORGANISATION Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA AMOUNT

GROUP / ORGANISATION AMOUNT AWARDED by LCDC Name of TOWN/VILLAGE AREA Annaduff ICA Annaduff €728 Aughameeney Residents Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Bornacoola Game & Conservation Club Bornacoola €728 Breffni Family Resource Centre Carrick on Shannon €728 Carrick-on Shannon & District Historical Society Carrick on Shannon €646 Castlefore Development Keshcarrigan €728 Eslin Community Association Eslin €729 Gorvagh Community Centre Gorvagh €729 Gurteen Residents Association Gurteen €100 Kiltubrid Church of Ireland Restoration Kiltubrid €729 Kiltubbrid GAA Kiltubrid €729 Knocklongford Residents Association Mohill €729 Leitrim Cycle Club Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Gaels Community Field LGFA Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Active Age Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village Development Leitrim Village €729 Leitrim Village ICA Leitrim Village €729 Mohill GAA Mohill €729 Mohill Youth Café Mohill €729 O Carolan Court Mohill €728 Rosebank Mens Group Carrick on Shannon €410 Saint Mary’s Close Residence Association Carrick on Shannon €728 Caisleain Hamilton Manorhamilton €1,000 Dromahair Arts & Recreation Centre Dromahair €946 Killargue Community Development Association Killargue €423 Kinlough Community Garden Kinlough €1,000 Manorhamilton ICA Manorhamilton €989 Manorhamilton Rangers Manorhamilton €100 North Leitrim Womens Centre Manorhamilton €757 Sextons House Manorhamilton €1,000 Tullaghan Development Association Tullaghan €1,000 Aughavas GAA Club Aughavas €750 Aughavas Men’s Shed Aughavas €769 Aughavas Parish Improvements Scheme Aughavas -

Blanchardstown Urban Structure Plan Development Strategy and Implementation

BLANCHARDSTOWN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT SPRING 2007 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION VISION, DEVELOPMENT THEMES AND OPPORTUNITIES PLANNING DEPARTMENT • SPRING 2007 David O’Connor, County Manager Gilbert Power, Director of Planning Joan Caffrey, Senior Planner BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION G A 01 SPRING 2007 P Contents Page INTRODUCTION . 2 SECTION 1: OBJECTIVES OF THE BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN – DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY 3 BACKGROUND PLANNING TO DATE . 3 VISION STATEMENT AND KEY ISSUES . 5 SECTION 2: DEVELOPMENT THEMES 6 INTRODUCTION . 6 THEME: COMMERCE RETAIL AND SERVICES . 6 THEME: SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY . 8 THEME: TRANSPORT . 9 THEME: LEISURE, RECREATION & AMENITY . 11 THEME: CULTURE . 12 THEME: FAMILY AND COMMUNITY . 13 SECTION 3: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES – ESSENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURAL IMPROVEMENTS 14 SECTION 4: DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AREAS 15 Area 1: Blanchardstown Town Centre . 16 Area 2: Blanchardstown Village . 19 Area 3: New District Centre at Coolmine, Porterstown, Clonsilla . 21 Area 4: Blanchardstown Institute of Technology and Environs . 24 Area 5: Connolly Memorial Hospital and Environs . 25 Area 6: International Sports Campus at Abbotstown. (O.P.W.) . 26 Area 7: Existing and Proposed District & Neighbourhood Centres . 27 Area 8: Tyrrellstown & Environs Future Mixed Use Development . 28 Area 9: Hansfield SDZ Residential and Mixed Use Development . 29 Area 10: North Blanchardstown . 30 Area 11: Dunsink Lands . 31 SECTION 5: RECOMMENDATIONS & CONCLUSIONS 32 BLANCHARDSTOWN URBAN STRUCTURE PLAN E G DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND IMPLEMENTATION A 02 P SPRING 2007 Introduction Section 1 details the key issues and need for an Urban Structure Plan – Development Strategy as the planning vision for the future of Blanchardstown. -

Annual Report 2020.Pdf

Leitrim County Council Comhairle Chontae Liatroma Leitrim County Council Annual Report 2020 1 #LoughMelvin Vision Our vision is to build an economically strong, creative and inclusive County Making Leitrim the best place to live, to work, to invest and to visit. Mission Statement We will place this vision at the centre of everything we do, and we will ensure that we develop policies, procedures and services that are fair and equitable and that we fulfil our statutory duty in having regard to human rights and equality in the performance and delivery of all our functions. Leitrim County Council Annual Report 2020 2 #AcresLakeBoardwalk Contents Introduction from An Cathaoirleach and Chief Executive ............................................................................................ 4 Elected Members of Leitrim County Council ................................................................................................................ 5 Leitrim County Council Strategic Policy Committee’s 2019 - 2024 .............................................................................. 6 Leitrim County Council Strategic Objectives and Supporting Strategies from the Corporate Plan 2019 - 2024 ......... 7 Delivering for Our People ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Housing .................................................................................................................................................................... -

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets Allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019

EONI-REP-223 - Streets - Streets allocated to a Polling Station by Area Local Council Elections: 02/05/2019 LOCAL COUNCIL: MID ULSTER DEA: CARNTOGHER ST JOHN'S PRIMARY SCHOOL (SWATRAGH), 30 MONEYSHARVAN ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA, BT46 5PY BALLOT BOX 1/CN TOTAL ELECTORATE 880 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000934 CARN VIEW, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QG N08000934 CHURCH WAY, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5UL N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5JA N08000934 FRIELS TERRACE, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QD N08000934 GARVAGH ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QE N08000934 GRANAGHAN PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5DY N08000934 KILREA ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QF N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QU N08000934 MAIN STREET, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QB N08000934 STONEY PARK, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5BE N08000934 UPPERLANDS ROAD, SWATRAGH, MAGHERA BT46 5QQ N08000934 TIMACONWAY ROAD, TIMACONWAY, KILREA BT51 5UF N08000934 BALLYNIAN LANE, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QP N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QR N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, BALLYNIAN, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 BEAGH ROAD, BEAGH (TEMPORAL), SWATRAGH BT46 5PX N08000934 CORLACKY HILL, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NP N08000934 DRUMBANE ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NR N08000934 KNOCKONEILL ROAD, CORLACKY, SWATRAGH BT46 5NX N08000934 CULNAGREW ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QX N08000934 GORTEADE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5RF N08000934 KILLYGULLIB ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QW N08000934 LISMOYLE ROAD, CULNAGREW, SWATRAGH BT46 5QU N08000934 HALFGAYNE ROAD, GRANAGHAN, SWATRAGH -

ENFORCEMENT of JUDGMENTS OFFICE W

ENFORCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS OFFICE NOTICE OF GRANT OF CERTIFICATES OF UNENFORCEAHILITY S Take Notice that the following certificates of unenforceability have been granted by the Enforcement of Judgments Office in respect of the following judgments DEBTOR CREDITOR Amount Amount Date of recoverable for which Date of judgment on foot of Certificate Certificate Full Name and Address Occupation Full Name and Address judgment issued James McMullan, Unemployed Edward McMahon, William 4 September 1972 £106.02 £106.02 20 February 1981 2 Azalea .Gardens, McMahon, James McMahon Twinbrook, Dunmurry, and Malachy McMahon, County Antrim trading as "Edward McMahon and Sons", w 183 Divis Street, Belfast J. S. Hamilton, trading as James McMullan, Unemployed 21 June 1972 £13.68 £13.68 20 February 1981 C/3 2 Azalea Gardens, Arthur & Co., H Twinbrook, Dunmurry, 12/20 Talbot Street, Belfast County Antrim Q> N trj Patrick McGeehan, Unemployed Dickson Bros., 30 December 1977 £54.92 £54.92 23 February 1981 H 46 Drumaney Road, Coagh, Garden Street, Cookstown, County Tyrone Magherafelt, 3 County Londonderry to Patrick McGeehan, Unemployed Seed Potato Marketing Board 16 April 1980 £181.20 £181.20 23 February 1981 46 Drumancy Road, Coagh, for Northern Ireland Cookstown, County Tyrone 2 Lincnhall Street, Belfast 50 2 Emily McDaniel, Unemployed Grattan Warehouses Ltd., 28 April 1980 £60.28 £60.28 13 February 1981 8 Lakeview, Fivemiletown, Anchor House, Inglesby County Tyrone Road, Bradford oo Thomas McDonald, Unemployed United Dominions Trust 12 October 1977 £264.09 £264.09