When Shannon Met Turing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APA Newsletter on Philosophy and Computers, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Spring

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Philosophy and Computers SPRING 2019 VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 FEATURED ARTICLE Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot Turing’s Mystery Machine ARTICLES Igor Aleksander Systems with “Subjective Feelings”: The Logic of Conscious Machines Magnus Johnsson Conscious Machine Perception Stefan Lorenz Sorgner Transhumanism: The Best Minds of Our Generation Are Needed for Shaping Our Future PHILOSOPHICAL CARTOON Riccardo Manzotti What and Where Are Colors? COMMITTEE NOTES Marcello Guarini Note from the Chair Peter Boltuc Note from the Editor Adam Briggle, Sky Croeser, Shannon Vallor, D. E. Wittkower A New Direction in Supporting Scholarship on Philosophy and Computers: The Journal of Sociotechnical Critique CALL FOR PAPERS VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2019 © 2019 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Computers PETER BOLTUC, EDITOR VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2019 Polanyi’s? A machine that—although “quite a simple” one— FEATURED ARTICLE thwarted attempts to analyze it? Turing’s Mystery Machine A “SIMPLE MACHINE” Turing again mentioned a simple machine with an Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot undiscoverable program in his 1950 article “Computing UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH, NZ Machinery and Intelligence” (published in Mind). He was arguing against the proposition that “given a discrete- state machine it should certainly be possible to discover ABSTRACT by observation sufficient about it to predict its future This is a detective story. The starting-point is a philosophical behaviour, and this within a reasonable time, say a thousand discussion in 1949, where Alan Turing mentioned a machine years.”3 This “does not seem to be the case,” he said, and whose program, he said, would in practice be “impossible he went on to describe a counterexample: to find.” Turing used his unbreakable machine example to defeat an argument against the possibility of artificial I have set up on the Manchester computer a small intelligence. -

The Turing Guide

The Turing Guide Edited by Jack Copeland, Jonathan Bowen, Mark Sprevak, and Robin Wilson • A complete guide to one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century • Covers aspects of Turing’s life and the wide range of his intellectual activities • Aimed at a wide readership • This carefully edited resource written by a star-studded list of contributors • Around 100 illustrations This carefully edited resource brings together contributions from some of the world’s leading experts on Alan Turing to create a comprehensive guide that will serve as a useful resource for researchers in the area as well as the increasingly interested general reader. “The Turing Guide is just as its title suggests, a remarkably broad-ranging compendium of Alan Turing’s lifetime contributions. Credible and comprehensive, it is a rewarding exploration of a man, who in his life was appropriately revered and unfairly reviled.” - Vint Cerf, American Internet pioneer JANUARY 2017 | 544 PAGES PAPERBACK | 978-0-19-874783-3 “The Turing Guide provides a superb collection of articles £19.99 | $29.95 written from numerous different perspectives, of the life, HARDBACK | 978-0-19-874782-6 times, profound ideas, and enormous heritage of Alan £75.00 | $115.00 Turing and those around him. We find, here, numerous accounts, both personal and historical, of this great and eccentric man, whose life was both tragic and triumphantly influential.” - Sir Roger Penrose, University of Oxford Ordering Details ONLINE www.oup.com/academic/mathematics BY TELEPHONE +44 (0) 1536 452640 POSTAGE & DELIVERY For more information about postage charges and delivery times visit www.oup.com/academic/help/shipping/. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

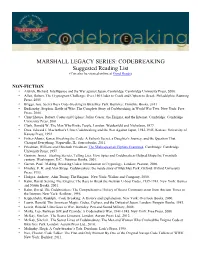

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F

An Early Program Proof by Alan Turing F. L. MORRIS AND C. B. JONES The paper reproduces, with typographical corrections and comments, a 7 949 paper by Alan Turing that foreshadows much subsequent work in program proving. Categories and Subject Descriptors: 0.2.4 [Software Engineeringj- correctness proofs; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]-assertions; K.2 [History of Computing]-software General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: A. M. Turing Introduction The standard references for work on program proofs b) have been omitted in the commentary, and ten attribute the early statement of direction to John other identifiers are written incorrectly. It would ap- McCarthy (e.g., McCarthy 1963); the first workable pear to be worth correcting these errors and com- methods to Peter Naur (1966) and Robert Floyd menting on the proof from the viewpoint of subse- (1967); and the provision of more formal systems to quent work on program proofs. C. A. R. Hoare (1969) and Edsger Dijkstra (1976). The Turing delivered this paper in June 1949, at the early papers of some of the computing pioneers, how- inaugural conference of the EDSAC, the computer at ever, show an awareness of the need for proofs of Cambridge University built under the direction of program correctness and even present workable meth- Maurice V. Wilkes. Turing had been writing programs ods (e.g., Goldstine and von Neumann 1947; Turing for an electronic computer since the end of 1945-at 1949). first for the proposed ACE, the computer project at the The 1949 paper by Alan M. -

August 2018 FACS a C T S

Issue 2018-1 August 2018 FACS A C T S The Newsletter of the Formal Aspects of Computing Science (FACS) Specialist Group ISSN 0950-1231 FACS FACTS Issue 2018-1 August 2018 About FACS FACTS FACS FACTS (ISSN: 0950-1231) is the newsletter of the BCS Specialist Group on Formal Aspects of Computing Science (FACS). FACS FACTS is distributed in electronic form to all FACS members. Submissions to FACS FACTS are always welcome. Please visit the newsletter area of the BCS FACS website for further details at: http://www.bcs.org/category/12461 Back issues of FACS FACTS are available for download from: http://www.bcs.org/content/conWebDoc/33135 The FACS FACTS Team Newsletter Editors Tim Denvir [email protected] Brian Monahan [email protected] Editorial Team Jonathan Bowen, John Cooke, Tim Denvir, Brian Monahan, Margaret West. Contributors to this issue Jonathan Bowen, John Cooke, Tim Denvir, Sofia Meacham. Brian Monahan, Bill Stoddart, Botond Virginas, Margaret West BCS-FACS websites BCS: http://www.bcs-facs.org LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/groups?gid=2427579 Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/BCS-FACS/120243984688255 Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BCS-FACS If you have any questions about BCS-FACS, please send these to Paul Boca [email protected] 2 FACS FACTS Issue 2018-1 August 2018 Editorial Dear readers, welcome to our first issue of FACS FACTS for 2018. This year, 2018, marks the 40th anniversary of FACS. At least one editor recalls an article by Dan Simpson, member of the editorial team at the time, FACS at 10 in 1988. -

Information Theory Techniques for Multimedia Data Classification and Retrieval

INFORMATION THEORY TECHNIQUES FOR MULTIMEDIA DATA CLASSIFICATION AND RETRIEVAL Marius Vila Duran Dipòsit legal: Gi. 1379-2015 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/302664 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement- NoComercial-CompartirIgual Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial- CompartirIgual This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike licence DOCTORAL THESIS Information theory techniques for multimedia data classification and retrieval Marius VILA DURAN 2015 DOCTORAL THESIS Information theory techniques for multimedia data classification and retrieval Author: Marius VILA DURAN 2015 Doctoral Programme in Technology Advisors: Dr. Miquel FEIXAS FEIXAS Dr. Mateu SBERT CASASAYAS This manuscript has been presented to opt for the doctoral degree from the University of Girona List of publications Publications that support the contents of this thesis: "Tsallis Mutual Information for Document Classification", Marius Vila, Anton • Bardera, Miquel Feixas, Mateu Sbert. Entropy, vol. 13, no. 9, pages 1694-1707, 2011. "Tsallis entropy-based information measure for shot boundary detection and • keyframe selection", Marius Vila, Anton Bardera, Qing Xu, Miquel Feixas, Mateu Sbert. Signal, Image and Video Processing, vol. 7, no. 3, pages 507-520, 2013. "Analysis of image informativeness measures", Marius Vila, Anton Bardera, • Miquel Feixas, Philippe Bekaert, Mateu Sbert. IEEE International Conference on Image Processing pages 1086-1090, October 2014. "Image-based Similarity Measures for Invoice Classification", Marius Vila, Anton • Bardera, Miquel Feixas, Mateu Sbert. Submitted. List of figures 2.1 Plot of binary entropy..............................7 2.2 Venn diagram of Shannon’s information measures............ 10 3.1 Computation of the normalized compression distance using an image compressor.................................... -

Combinatorial Reasoning in Information Theory

Combinatorial Reasoning in Information Theory Noga Alon, Tel Aviv U. ISIT 2009 1 Combinatorial Reasoning is crucial in Information Theory Google lists 245,000 sites with the words “Information Theory ” and “ Combinatorics ” 2 The Shannon Capacity of Graphs The (and) product G x H of two graphs G=(V,E) and H=(V’,E’) is the graph on V x V’, where (v,v’) = (u,u’) are adjacent iff (u=v or uv є E) and (u’=v’ or u’v’ є E’) The n-th power Gn of G is the product of n copies of G. 3 Shannon Capacity Let α ( G n ) denote the independence number of G n. The Shannon capacity of G is n 1/n n 1/n c(G) = lim [α(G )] ( = supn[α(G )] ) n →∞ 4 Motivation output input A channel has an input set X, an output set Y, and a fan-out set S Y for each x X. x ⊂ ∈ The graph of the channel is G=(X,E), where xx’ є E iff x,x’ can be confused , that is, iff S S = x ∩ x′ ∅ 5 α(G) = the maximum number of distinct messages the channel can communicate in a single use (with no errors) α(Gn)= the maximum number of distinct messages the channel can communicate in n uses. c(G) = the maximum number of messages per use the channel can communicate (with long messages) 6 There are several upper bounds for the Shannon Capacity: Combinatorial [ Shannon(56)] Geometric [ Lovász(79), Schrijver (80)] Algebraic [Haemers(79), A (98)] 7 Theorem (A-98): For every k there are graphs G and H so that c(G), c(H) ≤ k and yet c(G + H) kΩ(log k/ log log k) ≥ where G+H is the disjoint union of G and H. -

2020 SIGACT REPORT SIGACT EC – Eric Allender, Shuchi Chawla, Nicole Immorlica, Samir Khuller (Chair), Bobby Kleinberg September 14Th, 2020

2020 SIGACT REPORT SIGACT EC – Eric Allender, Shuchi Chawla, Nicole Immorlica, Samir Khuller (chair), Bobby Kleinberg September 14th, 2020 SIGACT Mission Statement: The primary mission of ACM SIGACT (Association for Computing Machinery Special Interest Group on Algorithms and Computation Theory) is to foster and promote the discovery and dissemination of high quality research in the domain of theoretical computer science. The field of theoretical computer science is the rigorous study of all computational phenomena - natural, artificial or man-made. This includes the diverse areas of algorithms, data structures, complexity theory, distributed computation, parallel computation, VLSI, machine learning, computational biology, computational geometry, information theory, cryptography, quantum computation, computational number theory and algebra, program semantics and verification, automata theory, and the study of randomness. Work in this field is often distinguished by its emphasis on mathematical technique and rigor. 1. Awards ▪ 2020 Gödel Prize: This was awarded to Robin A. Moser and Gábor Tardos for their paper “A constructive proof of the general Lovász Local Lemma”, Journal of the ACM, Vol 57 (2), 2010. The Lovász Local Lemma (LLL) is a fundamental tool of the probabilistic method. It enables one to show the existence of certain objects even though they occur with exponentially small probability. The original proof was not algorithmic, and subsequent algorithmic versions had significant losses in parameters. This paper provides a simple, powerful algorithmic paradigm that converts almost all known applications of the LLL into randomized algorithms matching the bounds of the existence proof. The paper further gives a derandomized algorithm, a parallel algorithm, and an extension to the “lopsided” LLL. -

Information Theory for Intelligent People

Information Theory for Intelligent People Simon DeDeo∗ September 9, 2018 Contents 1 Twenty Questions 1 2 Sidebar: Information on Ice 4 3 Encoding and Memory 4 4 Coarse-graining 5 5 Alternatives to Entropy? 7 6 Coding Failure, Cognitive Surprise, and Kullback-Leibler Divergence 7 7 Einstein and Cromwell's Rule 10 8 Mutual Information 10 9 Jensen-Shannon Distance 11 10 A Note on Measuring Information 12 11 Minds and Information 13 1 Twenty Questions The story of information theory begins with the children's game usually known as \twenty ques- tions". The first player (the \adult") in this two-player game thinks of something, and by a series of yes-no questions, the other player (the \child") attempts to guess what it is. \Is it bigger than a breadbox?" No. \Does it have fur?" Yes. \Is it a mammal?" No. And so forth. If you play this game for a while, you learn that some questions work better than others. Children usually learn that it's a good idea to eliminate general categories first before becoming ∗Article modified from text for the Santa Fe Institute Complex Systems Summer School 2012, and updated for a meeting of the Indiana University Center for 18th Century Studies in 2015, a Colloquium at Tufts University Department of Cognitive Science on Play and String Theory in 2016, and a meeting of the SFI ACtioN Network in 2017. Please send corrections, comments and feedback to [email protected]; http://santafe.edu/~simon. 1 more specific, for example. If you ask on the first round \is it a carburetor?" you are likely wasting time|unless you're playing the game on Car Talk. -

Online Communities: Visualization and Formalization

Online Communities: Visualization and Formalization Jonathan P. Bowen Museophile Limited, Oxford, UK [email protected] www.jpbowen.com Abstract. Online communities have increased in size and importance dramat- ically over the last decade. The fact that many communities are online means that it is possible to extract information about these communities and the con- nections between their members much more easily using software tools, despite their potentially very large size. The links between members of the community can be presented visually and often this can make patterns in the structure of sub-communities immediately obvious. The links and structures of layered com- munities can also be formalized to gain a better understanding of their modelling. This paper explores these links with some specific examples, including visualiza- tion of these relationships and a formalized model of communities using the Z notation. It also considers the development of such communities within the Com- munity of Practice social science framework. Such approaches may be applicable for communities associated with cybersecurity and could be combined for a better understanding of their development. 1 Introduction The development of collective human knowledge has always depended on communities. As communities have become more computer-based, it has become easier to monitor the activity of such interactions [7]. Recently the increasing use of online communities by the wider population (e.g., for social networking) has augmented the ways that com- munities can form and interact since geographical co-location is now much less critical than before the development of the Internet and the web [1,2].