First Occurrence of Limnoperna Fortunei (Dunker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

08/2014 Leticia De Paula Valente Estagiário De

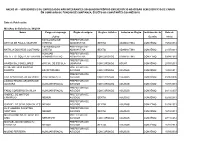

ANEXO VII – SERVIDORES E/OU EMPREGADOS NÃO INTEGRANTES DO QUADRO PRÓPRIO EM EXERCÍCIO NO ÓRGÃO SEM EXERCÍCIO DE CARGO EM COMISSÃO OU FUNÇÃO DE CONFIANÇA, EXCETO OS CONSTANTES DO ANEXO VI. -

Texto Integral

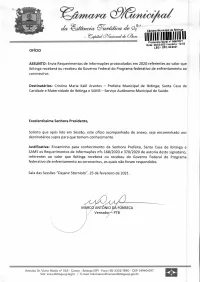

• ?séi>")/4C"'" '.^2e/iCt ti4- e 44.Ca (4 --- Camara Municipal de Ibitinga 1 E1111111Protocolo Geral n° 56612021 Data: 26/0212021 Horário: 10:53 LEG - OFC 30/2021 OFÍCIO ASSUNTO: Envia Requerimentos de Informações protocolados em 2020 referentes ao valor que Ibitinga receberá ou recebeu do Governo Federal do Programa federativo de enfrentamento ao coronavírus. Destinatários: Cristina Maria Kalil Arantes — Prefeita Municipal de Ibitinga; Santa Casa de Caridade e Maternidade de Ibitinga e SAMS — Serviço Autônomo Municipal de Saúde. Excelentíssima Senhora Presidente, Solicito que após lido em Sessão, este ofício acompanhado do anexo, seja encaminhado aos destinatários supra para que tomem conhecimento. Justificativa: Encaminho para conhecimento da Senhora Prefeita, Santa Casa de Ibitinga e SAMS os Requerimentos de Informações Os 168/2020 e 370/2020 de autoria deste signatário, referentes ao valor que Ibitinga receberá ou recebeu do Governo Federal do Programa federativo de enfrentamento ao coronavírus, os quais não foram respondidos. Sala das Sessões "Dejanir Storniolo", 25 de fevereiro de 2021. MARC ANTÔNIO 4Á FONSECA Vereador L PTB Avenida Dr. Victor Maida nº 563 - Centro - Ibitinga (SP) - Fone (16) 3352-7840 - CEP 14940-097 Site: www.ibitinga.sp.leg.br / E-mail: [email protected] )7ei"~n-t a9ir • /teil 9E1 • ;--• , -vo.;(ancur ..i~ra de C").)944:nrg - SP - ,:etA4,41L/YatÀrkna/e.k 1. (-amara municipal de lbitinga REQUERIMENTO 1111111111111111111111111 Protocolo Geral n° 2807/2020 Data: 04/12/2020 Horário: 12:24 LEG - REQ 370/2020 REITERA REQUERIMENTO N2 16812020 - REFERENTE AO VALOR QUE NOSSO MUNICÍPIO RECEBERÁ OU, RECEBEU DO GOVERNO FEDERAL, DO PROGRAMA FEDERATIVO DE ENFRENTAMENTO AO CORONAVÍRUS. -

Ibitinga-E - Listagem De Famílias Sorteadas Ordem Inscrição Nome Cpf Cônjuge / Co-Participante Cpf Grupo Faixa De Renda Status Classificação

IBITINGA-E - LISTAGEM DE FAMÍLIAS SORTEADAS ORDEM INSCRIÇÃO NOME CPF CÔNJUGE / CO-PARTICIPANTE CPF GRUPO FAIXA DE RENDA STATUS CLASSIFICAÇÃO 1 62400041812494 APARECIDA MARIA DOS SANTOS XXX.XXX.398-26 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 1 2 62400337842018 OCIONIDES GARCIA MAINARDES XXX.XXX.688-84 KAUA EZEQUIEL ZAMBIANCO MAINARDES XXX.XXX.738-17 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 2 3 62400452913405 DOUGLAS RODRIGO DE SOUZA XXX.XXX.298-10 APARECIDA FLORIPES RIBERO DE SALES XXX.XXX.088-29 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 3 4 62400606054340 DALILA GERUSA GABRIEL XXX.XXX.438-05 CHARLES CARDOSO XXX.XXX.298-65 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 4 5 62400680530747 FLAVIA LEITE DA SILVA XXX.XXX.418-01 MAURICIO SABINO DOS SANTOS XXX.XXX.158-36 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 5 6 62400643671891 PEDRO HENRIQUE TELES OLIVEIRA DO NASCIMENTO XXX.XXX.623-81 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 6 7 62400753060294 JOSE ROBERTO DE MIRANDA COELHO XXX.XXX.315-66 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 7 8 62400176882552 DEISE DAIANE CARDOSO DE OLIVEIRA XXX.XXX.178-40 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 8 9 62400199736907 MARCELO DE CHICO XXX.XXX.058-06 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 9 10 62400658853122 KATIUSCA GLAUSLIENS FERREIRA XXX.XXX.128-08 DEFICIENTE 01,00 A 05,00 SALÁRIOS MÍNIMOS BENEFICIÁRIO 10 11 62400559690617 JANETE APARECIDA FERREIRA DA SILVA XXX.XXX.928-00 LEANDRO DE -

Environmental Gradient in Reservoirs of the Medium and Low Tietê River

Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia, 2014, vol. 26, no. 1, p. 73-88 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2179-975X2014000100009 Environmental gradient in reservoirs of the medium and low Tietê River: limnological differences through the habitat sequence Gradiente ambiental em reservatórios do médio e baixo Rio Tietê: diferenças limnológicas ao longo da seqüência de habitats Welber Senteio Smith1,2, Evaldo Luis Gaeta Espíndola3 and Odete Rocha4 1Programa de Mestrado em Processos Tecnológicos e Ambientais, Universidade de Sorocaba – UNISO, Rodovia Raposo Tavares, km 92,5, CEP 18023-000, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] 2Laboratório de Ecologia Estrutural e Funcional, Universidade Paulista, Av. Independência, 210, CEP: 18087-101, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil 3Centro de Recursos Hídricos e Ecologia Aplicada, Universidade de São Paulo – USP, Av. Trabalhador São Carlense, CEP 13566-590, São Carlos, SP, Brazil e-mail: [email protected] 4Departamento de Ecologia e Biologia Evolutiva, Universidade Federal de São Carlos –UFSCar, Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP 310 , CEP 13565-905, São Carlos, SP, Brazil e-mail:[email protected] Abstract: Aim: The reservoirs of the medium and low Tietê River are disposed as a “cascade series”, in which time, physiographic features and influence from drainage basins present differences that determine variability in their dynamics. These reservoirs are submitted to different impacts from the urban centres which they drain, and also from agricultural activities.Considering these features, the aim of this work was to characterize the Medium and Low Tietê river stretches by limnological analysis (including water and sediments) considering dry and rainy seasons evaluating changes along the reservoirs sequence. -

A New Computing Environment for Modeling Species Distribution

EXPLORATORY RESEARCH RECOGNIZED WORLDWIDE Botany, ecology, zoology, plant and animal genetics. In these and other sub-areas of Biological Sciences, Brazilian scientists contributed with results recognized worldwide. FAPESP,São Paulo Research Foundation, is one of the main Brazilian agencies for the promotion of research.The foundation supports the training of human resources and the consolidation and expansion of research in the state of São Paulo. Thematic Projects are research projects that aim at world class results, usually gathering multidisciplinary teams around a major theme. Because of their exploratory nature, the projects can have a duration of up to five years. SCIENTIFIC OPPORTUNITIES IN SÃO PAULO,BRAZIL Brazil is one of the four main emerging nations. More than ten thousand doctorate level scientists are formed yearly and the country ranks 13th in the number of scientific papers published. The State of São Paulo, with 40 million people and 34% of Brazil’s GNP responds for 52% of the science created in Brazil.The state hosts important universities like the University of São Paulo (USP) and the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), the growing São Paulo State University (UNESP), Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Federal University of ABC (ABC is a metropolitan region in São Paulo), Federal University of São Carlos, the Aeronautics Technology Institute (ITA) and the National Space Research Institute (INPE). Universities in the state of São Paulo have strong graduate programs: the University of São Paulo forms two thousand doctorates every year, the State University of Campinas forms eight hundred and the University of the State of São Paulo six hundred. -

Endereços Cejuscs

PODER JUDICIÁRIO TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO Núcleo Permanente de Métodos Consensuais de Solução de Conflitos Fórum João Mendes Junior, 13º andar – salas 1301/1311 E-mail: [email protected] CENTROS JUDICIÁRIOS DE SOLUÇÃO DE CONFLITOS E CIDADANIA – CEJUSCs ÍNDICE (Clicar na localidade desejada para obtenção do endereço, telefone e e-mail) SÃO PAULO – CAPITAL .............................................................................................................. 7 Cejusc Central – Fórum João Mendes Jr .................................................................................... 7 Butantã - Foro Regional XV ....................................................................................................... 8 Itaquera - Guaianazes - Foro Regional VII .................................................................................. 8 Jabaquara - Foro Regional III ..................................................................................................... 9 Lapa - Foro Regional IV.............................................................................................................. 9 Nossa Senhora do Ó - Foro Regional XII ..................................................................................... 9 Pinheiros - Foro Regional XI....................................................................................................... 9 Santana - Foro Regional I ........................................................................................................ 10 Santo Amaro - Foro -

Unidades De IPORANGA IGUAPE ITAPIRAPUA PAULISTA RIBEIRA ITAOCA Divisão Municipal Alambiques PARIQUERA-ACU CAJATI JACUPIRANGA

Distribuição Espacial de Alambiques, 2007/2008 OUROESTE POPULINA INDIAPORA MESOPOLIS MIRA ESTRELA SANTA ALBERTINA RIOLANDIA RIFAINA SANTA CLARA D OESTE PARANAPUA GUARANI DO OESTE CARDOSO PAULO DE FARIA IGARAPAVA TURMALINA SANTA RITA DO OESTE MACEDONIA DOLCINOPOLIS ARAMINA URANIA FERNANDOPOLIS PONTES GESTAL RUBINEIA ASPASIA MIGUELOPOLIS VITORIA BRASIL ORINDIUVA BURITIZAL PEDRANOPOLIS PEDREGULHO SANTA FE DO SULSANTANA DA PONTE PENSA VOTUPORANGA SANTA SALETE ESTRELA DO OESTE TRES FRONTEIRAS FERNANDOPOLIS COLOMBIA JALES PARISIALVARES FLORENCE AMERICO DE CAMPOS PALESTINA GUAIRA ITUVERAVA JALES JERIQUARA NOVA CANAA PAULISTA SAO FRANCISCO ICEM GUARACI CRISTAIS PAULISTA ILHA SOLTEIRA SAO JOAO DAS DUAS PONTES MERIDIANO VALENTIM GENTIL IPUA PALMEIRA DO OESTE COSMORAMA RIBEIRAO CORRENTE DIRCE REISPONTALINDA VOTUPORANGA SUZANAPOLISAPARECIDA DO OESTE NOVA GRANADA GUARA MARINOPOLIS ORLANDIA BARRETOS SAO JOAO DE IRACEMA TANABI ALTAIR SAO JOAQUIM DA BARRA FRANCA ITAPURA MAGDA MIRASSOLANDIA SAO JOSE DA BELA VISTA ONDA VERDE GUZOLANDIA GENERAL SALGADO SEBASTIANOPOLIS DO SUL BARRETOS AURIFLAMA IPIGUA FLOREAL JABORANDI RESTINGA ITIRAPUA PEREIRA BARRETO SUD MENNUCCI NHANDEARA MORRO AGUDO BALSAMO OLIMPIA ORLANDIA NUPORANGA GENERAL SALGADO MONTE APRAZIVEL POLONI GUAPIACU COLINA PATROCINIO PAULISTA NOVA CASTILHO TERRA ROXA SAO JOSE DO RIO PRETO SEVERINIA FRANCA GASTAO VIDIGAL ANDRADINA MACAUBAL MIRASSOL SALES OLIVEIRA SANTO ANTONIO DO ARACANGUA NOVA LUSITANIA MONCOES NEVES PAULISTA BATATAIS CAJOBI VIRADOURO CASTILHO UNIAO PAULISTA NIPOA CEDRAL MONTE AZUL PAULISTA -

Plano De Ação Regional Para O Atendimento Às Pessoas Vítimas De Acidentes Por Escorpião

Secretaria de Estado da Saúde Plano de Ação Regional Para o Atendimento às Pessoas Vítimas de Acidentes por Escorpião Região Centro-Oeste do DRS III – Araraquara 2019 Coordenadoria de Regiões de Saúde - CRS Departamento Regional de Saúde de Araraquara - DRS III Avenida Espanha, 188, 4º andar | CEP 14801-130 | Araraquara, SP | Fone: (16) 3301-1867 srss [email protected] Secretaria de Estado da Saúde Caracterização da Região Centro-Oeste do DRS III - Araraquara A Região de Saúde (RS) Centro Oeste do Departamento Regional de Saúde de Araraquara – DRS III Araraquara – está situada na área centro oeste da Região Administrativa de Governo denominada Central. A RS é constituída por cinco municípios, sendo Borborema, Ibitinga, Itápolis, Nova Europa e Tabatinga, com estimativa populacional de 141.879 habitantes (IBGE 2015). Esta localizada na divisa das regiões Norte e Central do DRS III e com as regiões de saúde de Jaú e Bauru, do DRS VI de Bauru e a região de Catanduva do DRS XV de São José do Rio Preto. Itápolis Borborema Tabatinga Ibitinga Nova Europa Os municípios da RS apresentam dificuldades de locomoção no território devida a insuficiência de veículos para transporte tanto dos usuários quanto dos profissionais de saúde impossibilitando o acesso a serviços de saúde localizados em outras regiões de saúde. Dificuldade apresentada principalmente pelos municípios de Borborema e Tabatinga. Existe na região predomínio de municípios com pequeno porte populacional, sendo que, 4 possuem menos de 50mil habitantes e 1 tem entre 50 a 100 mil habitantes. Coordenadoria de Regiões de Saúde - CRS Departamento Regional de Saúde de Araraquara - DRS III Avenida Espanha, 188, 4º andar | CEP 14801-130 | Araraquara, SP | Fone: (16) 3301-1867 srss [email protected] Secretaria de Estado da Saúde Na análise do perfil demográfico por sexo, a proporção de homens em relação à de mulheres começa a se alterar e os municípios de Borborema, Ibitinga e Tabatinga apresentam maior população masculina. -

MUNICÍPIO MÓDULO FISCAL - MF (Ha) (Ha)

QUATRO MFs MUNICÍPIO MÓDULO FISCAL - MF (ha) (ha) ADAMANTINA 20 80 ADOLFO 22 88 AGUAÍ 18 72 ÁGUAS DA PRATA 22 88 ÁGUAS DE LINDÓIA 16 64 ÁGUAS DE SANTA BÁRBARA 30 120 ÁGUAS DE SÃO PEDRO 18 72 AGUDOS 12 48 ALAMBARI 22 88 ALFREDO MARCONDES 22 88 ALTAIR 28 112 ALTINÓPOLIS 22 88 ALTO ALEGRE 30 120 ALUMÍNIO 12 48 ÁLVARES FLORENCE 28 112 ÁLVARES MACHADO 22 88 ÁLVARO DE CARVALHO 14 56 ALVINLÂNDIA 14 56 AMERICANA 12 48 AMÉRICO BRASILIENSE 12 48 AMÉRICO DE CAMPOS 30 120 AMPARO 20 80 ANALÂNDIA 18 72 ANDRADINA 30 120 ANGATUBA 22 88 ANHEMBI 30 120 ANHUMAS 24 96 APARECIDA 24 96 APARECIDA D'OESTE 30 120 APIAÍ 16 64 ARAÇARIGUAMA 12 48 ARAÇATUBA 30 120 ARAÇOIABA DA SERRA 12 48 ARAMINA 20 80 ARANDU 22 88 ARAPEÍ 24 96 ARARAQUARA 12 48 ARARAS 10 40 ARCO-ÍRIS 20 80 AREALVA 14 56 AREIAS 35 140 AREIÓPOLIS 16 64 ARIRANHA 16 64 ARTUR NOGUEIRA 10 40 ARUJÁ 5 20 ASPÁSIA 26 104 ASSIS 20 80 ATIBAIA 16 64 AURIFLAMA 35 140 AVAÍ 14 56 AVANHANDAVA 30 120 AVARÉ 30 120 BADY BASSITT 16 64 BALBINOS 20 80 BÁLSAMO 20 80 BANANAL 24 96 BARÃO DE ANTONINA 20 80 BARBOSA 30 120 BARIRI 16 64 BARRA BONITA 14 56 BARRA DO CHAPÉU 16 64 BARRA DO TURVO 16 64 BARRETOS 22 88 BARRINHA 12 48 BARUERI 7 28 BASTOS 16 64 BATATAIS 22 88 BAURU 12 48 BEBEDOURO 14 56 BENTO DE ABREU 30 120 BERNARDINO DE CAMPOS 20 80 BERTIOGA 10 40 BILAC 30 120 BIRIGUI 30 120 BIRITIBA-MIRIM 5 20 BOA ESPERANÇA DO SUL 12 48 BOCAINA 16 64 BOFETE 20 80 BOITUVA 18 72 BOM JESUS DOS PERDÕES 16 64 BOM SUCESSO DE ITARARÉ 20 80 BORÁ 20 80 BORACÉIA 16 64 BORBOREMA 16 64 BOREBI 12 48 BOTUCATU 20 80 BRAGANÇA PAULISTA 16 64 BRAÚNA -

134 – São Paulo, 130 (250) Diário Oficial Poder Executivo

134 – São Paulo, 130 (250) Diário Ofi cial Poder Executivo - Seção I quinta-feira, 17 de dezembro de 2020 FIAT UNO S; 1986/1986; JOSE CARLOS FORTUNATO LEITE 1988/1988; MARCOS SALVADOR CARVALHO; RENAVAM: 0603; PLACA: GPC1532; PARAGUACU/MG; CHASSI: DANI- 0650; PLACA: BKE1628; TABATINGA/SP; CHASSI: BH739809; JUNIOR; RENAVAM: 00355563428. 00415231159. FICADO; MOTOR: 18A31013084; GM; MONZA SL; 1985/1985; MOTOR: SUCATA REPOS PECAS; VW; KOMBI; 1982/1982; JOSE 0495; PLACA: BSF0678; BORBOREMA/SP; CHASSI: 0548; PLACA: BYB1129; IBITINGA/SP; CHASSI: REGINALDO GONCALVES BARBUDO - ANTONIO ANDRE MEN- APARECIDO ROSSETTO; RENAVAM: 00412077973. 9BWZZZ327SP048946; MOTOR: UDB044583; VW; SANTANA CL 9BFZZZ33ZRP020091; MOTOR: UR083527; FORD; VERSAILLES DES; RENAVAM: 00185282962. 0651; PLACA: HQM5108; ITAPUI/SP; CHASSI: 9BFCXXLB- 1800 I; 1995/1996; DIEGO APARECIDO VALENCA CARVALHO 2.0 GL; 1994/1994; BRUNO CORREA ANDREOLI; RENAVAM: 0604; PLACA: COV0674; BOA ESPERANCA DO SUL/SP; 2CDP96375; MOTOR: 075232; FORD; DEL REY OURO; 1983/1984; - PAULO SERGIO DO NASCIMENTO; RENAVAM: 00645662054. 00621432156. CHASSI: 9BD14600003108742; MOTOR: SUCATA REPOS PECAS; DOUGLAS MENDES FIGUEIREDO; RENAVAM: 00130176737. 0496; PLACA: ACA1324; SANTA FE/PR; CHASSI: 0549; PLACA: CXS3770; MATAO/SP; CHASSI: LB4KUS92269; FIAT; UNO CS; 1986/1986; MARIA SOARES DE PINHO - ELAINE 0652; PLACA: BFH0182; SAO CARLOS/SP; CHASSI: 9BD146000M3754172; MOTOR: 146B5011*3402100*; FIAT; MOTOR: SEM CADASTRO; FORD; CORCEL II LDO; 1978/1978; FERREIRA; RENAVAM: 00268643113. 9BWZZZ30ZMT056374; MOTOR: SUCATA REPOS PECAS; VW; UNO S 1.5; 1991/1991; ANTONIO BENITE NUNES; RENAVAM: NELSON CUZIN - DINAMIL APARECIDA DE ALMEIDA; RENAVAM: 0606; PLACA: CJZ6716; IBITINGA/SP; CHASSI: FB025380; GOL GL 1.8; 1991/1991; DAVI GOMES DOS SANTOS DE MORAES 00600254933. 00366323385. MOTOR: 18A31064927; GM; MONZA SL; 1985/1985; VALDIR - BRUNA PORTO; RENAVAM: 00433260572. -

Rede Sf Odonto

REDE SF ODONTO PRESTADOR CIDADE UF ESPECIALIDADE TIPO ENDEREÇO TELEFONE AVENIDA MOREIRA CESAR, 144 - VILA 3D IMAGE SERVICE DIGITAL RSM SOROCABA SP RADIOLOGIA ESPECIALIZADA CLINICA GRANDINO - SOROCABA-SP CEP TEL. 15 30330808 LTDA - ME 18.010-010 AVENIDA FRANCISCO GLICERIO, 1046 A ODONTOLOGIA CAMPINAS SP CLINICO GERAL, ENDODONTIA CLINICA 3° ANDAR TORRE 33 - CENTRO - TEL. 19 33883128 CAMPINAS-SP CEP 13.012-100 CIRURGIAS, CLINICO GERAL, DEN- RUA DUQUE DE CAXIAS, 642 SALA TEL. 19 25192080 A ODONTOLOGIA SELECT CAMPINAS SP TISTICA, ENDODONTIA, ODONTOPE- DENTISTA 62 - CENTRO - CAMPINAS-SP CEP TEL. 19 32018696 DIATRIA, PERIODONTIA 13.015-311 CIRURGIAS, CLINICO GERAL, DEN- AVENIDA FRANCISCO GLICERIO, 1046 A ODONTOLOGIA SELECT CAMPINAS SP TISTICA, ENDODONTIA, ODONTOPE- DENTISTA SALA 46 - CENTRO - CAMPINAS-SP TEL. 19 32018306 DIATRIA, PERIODONTIA CEP 13.012-000 CIRURGIAS, CLINICO GERAL, ENDO- AVENIDA INDEPENDENCIA, 705 - VILA A.M. ODONTOLOGIA VALINHOS SP CLINICA TEL. 19 38698110 DONTIA OLIVO - VALINHOS-SP CEP 13.276-030 RUA GONCALVES DIAS, 1525 - CEN- CLINICO GERAL, DENTISTICA, PERIO- ACACIO GALEAZZI JUNIOR ARARAQUARA SP DENTISTA TRO - ARARAQUARA-SP CEP 14.801- TEL. 16 33360566 DONTIA, PROTESE DENTAL 290 AVENIDA DOUTOR RUDGE RAMOS, 110 ACOLON ODONTOLOGIA S/C LTDA. SAO BERNARDO SP CLINICO GERAL DENTISTA - RUDGE RAMOS - SAO BERNARDO DO TEL. 11 43673978 - ME DO CAMPO CAMPO-SP CEP 09.636-000 RUA RUA DOS BANDEIRANTES, 174 CLINICO GERAL, ENDODONTIA, OD- TEL. 19 25156666 ACQUA ODONTO CAMPINAS SP CLINICA SALA 1 - CAMBUI - CAMPINAS-SP CEP ONTOPEDIATRIA, PERIODONTIA TEL. 19 25176666 13.024-010 RUA JOAO BATISTA FERNANDES, 758 ADALTO CESAR COUTO FERREIRA IBIRA SP CIRURGIAS, CLINICO GERAL DENTISTA TEL. -

CDI - Centro Dia Do Idoso

CDI - Centro Dia do Idoso MUNICÍPIO ENDEREÇO DA OBRA Rua Domingos Leão, esq. com a Av. Rubens Agudos Venturini. – Vila Avato (Agudos E) Americana R. das Acácias, s/ nº - Jd. Glória Rua Pedro Alves de Siqueira s/nº, Jardim Amparo Cecap Apiaí Rua Espírito Santo – Bairro Cordeirópolis Av. Mário Ybarra de Almeida, 1011 – Bairro do Araraquara Carmo Araras Av. José Ometto – Jd. 8 de Abril Rua Luiz Gonzaga Colangelo Nóbrega, nº 151 Arujá – Parque Rodrigo Barreto Rua José Floriano Pereira, 211 – Conjunto Assis Habitacional Orestes Longhini Atibaia Rua dos Manacás da Serra x Rua dos Alecrins Rua Abílio Garcia e Rua Fernando de Moraes Avaré s/nº – Jd. Planalto Barretos Oquisição de equipamento Rua Victor Leandro Domingues, N. H. Mary Bauru Dota, setor 4, quadra 2.043 Bebedouro Alameda Sabará – Jd. Do Bosque Birigui Avenida Vitória Régia,s/n - JD São Braz Bocaina R. Augusto Giachini, s/n – Jd. São José Botucatu R. Benedito Mathias Blumer, 354 – Jd. Paraíso Bragança Paulista R. Euzébio Savaio s/nº - Bairro Lavapes Caieiras Rua Antônio Michelino – Vila dos Pinheiros Capão Bonito R. Marechal Deodoro, nº 05 - Centro Capela do Alto Rua 1 x Rua 2 – Jd. Casa Grande Catanduva Rua Araraquara,767 – Vila Rodrigues R. Virgilio Capelini x R. N. Sra. Aparecida – Dois Córregos Residencial Cidade Amizade Dracena Av. Chacom Couto, 1393 – Bairro Metrópole Espírito Santo do Pinhal Rua Eurico de Souza Lima – Pq. da Figueira Rua Voluntário Adriano Cintra, s/n, área Franca institucional Rua Tunis s/nº - Bairro Vila Ramos - Parque Franco da Rocha Vitória R. Idúlia da Costa Vilela, 465 – Residencial Ibitinga Jardim Pacola Ilha Solteira R.