Variation, Tranformation and Development in Gérard Grisey’S Les Espaces Acoustiques Alex Vaughan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concerto for Clarinet for Solo B Clarinet, Chamber Orchestra and Electronics B

MITYA Concerto for Clarinet for solo B clarinet, chamber orchestra and electronics b Taylor Brook 2010 Score in C Instrumentation flute (+ piccolo) oboe Bb clarinet tenor saxophone baritone saxophone Bassoon horn trumpet in C (cup, straight and harmon mutes) trombone (cup, straight and harmon mutes) tuba solo Bb clarinet 2 percussion: I - 3 sizzle cymbals I - 3 suspended cymbals I - vibraphone I - almglocken (A3, D4, E4, A4 and B4) I - crotale (G6 only) I - lion’s roar I - bass drum I - pitched gongs (D3 and A3) II - almglocken (B3, C#4, F#4 and G#4) II - 3 sizzle cymbals II - pitched gongs (E3, A3 and D4) II - 3 timpani (32”, 29” and 26”) II - wine glass (D5) II - tubular bells harp 2 violins viola cello contrabass MIDI keyboard (77 or more keys) electronics (see performance instructions for details) Concert Notes Mitya, a clarinet concerto by Taylor Brook, was composed in partial fulfilment of the Master’s of Music degree at McGill University, under the supervision of Brian Cherney and Sean Ferguson. Mitya is dedicated to the clarinetist Mark Bradley. The title of this clarinet concerto is a reference to Kitty and Levin’s son in Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. In the final chapters of the novel, Tolstoy describes the process of conception, pregnancy, birth and infancy from the perspective of the father. Simply put, the emotional state of the father, Levin, moves from confusion and fear to understanding and acceptance. In addition to informing the composition on a purely abstract level, I also used passages of the novel to develop the large-scale form and structure of the work. -

Modèles D'instruments Pour L'aide À L'orchestration

THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Spécialité Acoustique, traitement du signal et informatique appliqués à la musique Présentée par M. Damien Tardieu Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR de l’UNIVERSITÉ PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Sujet de la thèse : Modèles d’instruments pour l’aide à l’orchestration soutenue le 15/12/2008 devant le jury composé de : M. Xavier Rodet Directeur de thèse M. Philippe Leray Rapporteur M. François Pachet Rapporteur M.Gaël Richard Examinateur M.Stephen McAdams Examinateur M.Jean Dominique Polack Examinateur M.Geoffroy Peeters Examinateur Université Pierre & Marie Curie - Paris 6 Tél. Secrétariat : 01 42 34 68 35 Bureau d’accueil, inscription des doctorants et base de Fax : 01 42 34 68 40 données Tél. pour les étudiants de A à EL : 01 42 34 69 54 Esc G, 2ème étage Tél. pour les étudiants de EM à ME : 01 42 34 68 41 15 rue de l’école de médecine Tél. pour les étudiants de MF à Z : 01 42 34 68 51 75270-PARIS CEDEX 06 E-mail : [email protected] 2 3 Résumé Modèles d’instruments pour l’aide à l’orchestration Cette thèse traite de la conception d’une nouvelle méthode d’orchestration assistée par ordinateur. L’orchestration est considérée ici comme l’art de manipuler le timbre d’un orchestre par l’assemblage des timbres des différents instruments. Nous proposons la formulation suivante du problème de l’or- chestration assistée par ordinateur : Il consiste à trouver les combinaisons de sons instrumentaux dont le timbre se rapproche le plus possible d’un timbre cible fournit par le compositeur. -

Perceptual and Semantic Dimensions of Sound Mass

PERCEPTUAL AND SEMANTIC DIMENSIONS OF SOUND MASS Jason Noble Composition Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal April 2018 A dissertation submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Jason Noble 2018 In memory of Eleanor Stubley, Clifford Crawley, and James Bradley, for whose guidance and inspiration I am eternally grateful Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................................v Résumé ................................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgments................................................................................................................xi Contributions of Authors ......................................................................................................xiii List of Figures ......................................................................................................................xiv List of Tables .......................................................................................................................xvii Introduction ....................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Perceptual Dimensions of Sound Mass .............................................5 1.1 Introduction: Defining ‘Sound Mass’ .........................................................................5 -

Temporal Structures and Timbral Transformations in Gérard Grisey’S Modulations and Release for 12 Musicians, an Original Composition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt EMPTY SPACES: TEMPORAL STRUCTURES AND TIMBRAL TRANSFORMATIONS IN GÉRARD GRISEY’S MODULATIONS AND RELEASE FOR 12 MUSICIANS, AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION by Nizan Leibovich B.M, Tel Aviv University, 1993 M.M, Carnegie Mellon University, 1996 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Composition and Theory University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCEINCES This dissertation was presented by Nizan Leibovich It was defended on January 20th, 2017 and approved by David Pettersen, Associate Professor of French; Department of French and Italian Languages and Literatures and Film Studies Program Department Mathew Rosenblum, Professor of Music, Music Department Amy Williams, Assistant Professor of Music, Music Department Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Music, Music Department ii Copyright © by Nizan Leibovich 2017 iii EMPTY SPACES: TEMPORAL STRUCTURES AND TIMBRAL TRANSFORMATIONS IN GÉRARD GRISEY’S MODULATIONS AND RELEASE FOR 12 MUSICIANS, AN ORIGINAL COMPOSITION Nizan Leibovich, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 Gérard Grisey’s Modulations (1976-77) is the fourth installment of Les espaces acoustiques, a six-piece cycle inspired by the composer’s analysis of brass instruments’ E-based harmonic spectrum. This dissertation concentrates on Grisey’s approach to the temporal evolution of Modulations, and how his temporal structuring affects perception of the piece’s continuum. The analysis discerns and examines eight temporal structures spread over three larger parts. -

Introduction to the Pitch Organization of French Spectral Music Author(S): François Rose Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol

Introduction to the Pitch Organization of French Spectral Music Author(s): François Rose Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Summer, 1996), pp. 6-39 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833469 Accessed: 24/10/2010 16:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pnm. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music. http://www.jstor.org INTRODUCTION TO THE PITCH ORGANIZATION OF FRENCH SPECTRALMUSIC FRANCOISROSE INTRODUCTION G tRARD GRISEY(b.1946) and Tristan Murail (b. -

Analytical Explorations of Spectral Mixed Music

Musical Engagements with Technology: Analytical Explorations of Spectral Mixed Music Lesley Friesen Schulich School of Music, Department of Music Research McGill University, Montréal August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. © Lesley Friesen, 2015. 2 Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction and Background 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 The Dualism of Mixed Music – At the Intersection of Two Music Traditions .................. 11 1.3 Classifying Relationships in Mixed Works ........................................................................ 15 1.4 Spectralism and Ambiguity................................................................................................. 18 1.5 “Music for Human Beings:” Psychoacoustics and Auditory Scene Analysis .................... 22 2. Mapping out Methodologies 2.1 Geography of Analysis ...................................................................................................... -

Introduction to the Pitch Organization of French Spectral Music Author(S): François Rose Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol

Introduction to the Pitch Organization of French Spectral Music Author(s): François Rose Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Summer, 1996), pp. 6-39 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833469 Accessed: 02/03/2010 10:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pnm. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music. http://www.jstor.org INTRODUCTION TO THE PITCH ORGANIZATION OF FRENCH SPECTRALMUSIC FRANCOISROSE INTRODUCTION G tRARD GRISEY(b.1946) and Tristan Murail (b. -

Hearing Images and Seeing Sound: the Creation of Sonic Information Through Image Interpolation

Hearing Images and Seeing Sound: The Creation of Sonic Information Through Image Interpolation Maxwell Dillon Tfirn Charlottesville, VA B.M., University of Florida, 2009 M.A., Wesleyan University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music University of Virginia April, 2017 ii © Copyright by Maxwell Dillon Tfirn All Rights Reserved March 2017 iii Abstract This dissertation focuses on the compositional use of spectra, from the inception of this approach in the focus on acoustic characteristics of sound to my own approach, using images and raw data as spectral generators. I create these spectra using image interpolation and processing, and map them from the visual to the auditory domain. I situate my work in relation to the French and Romanian spectralists, the German Feedback Group, and other offshoots whose starting point is timbre-based composition. My own suite of software translates images into sound, allows for the creation and deletion of images, thus altering the sound, and supports analysis of the resultant spectra. Finally, the application of my software and techniques is illustrated in three of my compositions: Establish, Corrupt, Broken for 8-channel fixed media, Laniakea Elegant Beauty for Chamber Ensemble, and Invisible Signals for open instrumentation. iv Acknowledgements My dearest thanks go to my advisor, Judith Shatin. Her amazing insights and editorial expertise made this dissertation possible. I have enjoyed working with her during my years at UVA on a number of interesting projects and her continued support and critical questions have helped me to grow as a composer and artist. -

MUS434-571.3 Music of the Modern Era Spectral Music – Apr

MUS434-571.3 Music of the Modern Era Spectral Music – Apr. 18, 2013 Frequency Spectrum • Hearing range 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz) Spectral Analysis (FFT) Spectral Music • Timbre is created by each sound’s unique spectral content • FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) is the process by which one analyzes a sound’s spectrum over time • More scientific and perceptive approach to composition – Acoustics / Physics of Sound – Focus on timbre through exploration of the overtone series – Electronic music principles and techniques with acoustic instruments Overtone Series Spectral Music • Sonority = any group of pitches • Harmonicity – using overtones in a sonority • Inharmonicity – using tones that are not overtones in sonority • Formant – strongest frequencies (“vowel sound”) • Microphony – “zoomed in” perception of sound (sustain/decay) • Macrophony – sound events perceived over time • Subharmonicity – Invert intervallic relationships of overtones (large intervals on top, small microtonal relationships on bottom) Gérard Grisey – Partiels (1975) • One of six pieces from Espaces Acoustiques • Based on overtone series of low trombone E • Stable sonority gradually altered, noise added – Inhalation (increased activity / instability) – Exhalation (restoring order) – Rest (on E fundamental) • Temporal processes applied – Spectral polyphony – counterpoint between timbres (sonorities) Tristan Murail – Gondwana (1980) Frequency Modulation Ring Modulation Ring Modulation • Additive synthesis yields summation and difference tones • 500 Hz wave modulated by 700 -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 28-May-2010 I, Dominic DeStefano , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Viola It is entitled: A Guide to the Pedagogy of Microtonal Intonation in Recent Viola Repertoire: Prologue by Gérard Grisey as Case Study Student Signature: Dominic DeStefano This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Catharine Carroll, DMA Catharine Carroll, DMA 5/28/2010 777 A Guide to the Pedagogy of Microtonal Intonation in Recent Viola Repertoire: Prologue by Gérard Grisey as Case Study a document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music May 28, 2010 by Dominic DeStefano 3407 Clifton Ave Apt 23 Cincinnati, OH 45220 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 ____________________________________ Advisor: Catharine Carroll, DMA ____________________________________ Reader: Masao Kawasaki ____________________________________ Reader: Lee Fiser Abstract Since its establishment as a solo instrument, the viola’s repertoire has always heavily depended upon the works of composers contemporary with its first great soloists. As this dependence on recent repertoire continues, the viola boasts a growing number of works containing microtonal pitch collections, and the modern performer and pedagogue must have the skills to interpret these works. This document serves as a guide to the intonation of microtonal viola repertoire, asserting that the first step lies in understanding the pitch collections from the composer’s point of view. -

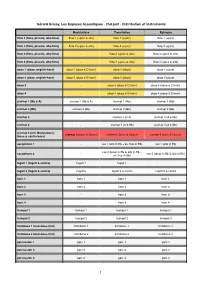

LEA Instruments Distribution

Gérard Grisey, Les Espaces Acoustiques - 2nd part - Distribution of instruments Modulations Transitoires Epilogue flute 1 (flute, piccolo, alto-flute) flute 1 (+picc & alto) flute 1 (+picc) flute 1 (+picc) flute 2 (flute, piccolo, alto-flute) flute 2 (+picc & alto) flute 2 (+picc) flute 2 (+picc) flute 3 (flute, piccolo, alto-flute) - flute 3 (+picc & alto) flute 3 (+picc & alto) flute 4 (flute, piccolo, alto-flute) - flute 4 (+picc & alto) flute 4 (+picc & alto) oboe 1 (oboe, english-horn) oboe 1 (oboe & E-horn) oboe 1 (oboe) oboe 1 (oboe) oboe 2 (oboe, english-horn) oboe 2 (oboe & E-horn) oboe 2 (oboe) oboe 2 (oboe) oboe 3 - oboe 3 (oboe & E-horn) oboe 3 (oboe & E-horn) oboe 4 - oboe 4 (oboe & E-horn) oboe 4 (oboe & E-horn) clarinet 1 (Bb & A) clarinet 1 (Bb & A) clarinet 1 (Bb) clarinet 1 (Bb) clarinet 2 (Bb) clarinet 2 (Bb) clarinet 2 (Bb) clarinet 2 (Bb) clarinet 3 - clarinet 3 (in A) clarinet 3 (A & Bb) clarinet 4 - clarinet 4 (A & Bb) clarinet 4 (A & Bb) clarinet 5 (3 in Modulations) clarinet 3 (bass & Cbass) clarinet 5 (bass & Cbass) clarinet 5 (bass & Cbass) (bass & contra-bass) saxophone 1 - sax 1 (alto in Eb + ev. Sop in Bb) sax 1 (alto in Eb) sax 2 (tenor in Bb & alto in Eb + saxophone 2 - sax 2 (tenor in Bb & alto in Eb) ev. sop in Bb) fagott 1 (fagott & contra) fagott 1 fagott 1 fagott 2 (fagott & contra) fagott 2 fagott 2 & contra fagott 2 & contra horn 1 horn 1 horn 1 horn 1 horn 2 horn 2 horn 2 horn 2 horn 3 - horn 3 horn 3 horn 4 - horn 4 horn 4 trumpet 1 trumpet 1 trumpet 1 trumpet 1 trumpet 2 trumpet 2 trumpet 2 trumpet 2 trombone 1 tenor-bass -

Mason Dissertation Complete

Feeling Machines: Immersion, Expression, and Technological Embodiment in Electroacoustic Music of the French Spectral School William Mason Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 William Mason All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Feeling Machines: Immersion, Expression, and Technological Embodiment in Electroacoustic Music of the French Spectral School William Mason This dissertation considers the music and technical practice of composers affiliated with French spectralism, including Hugues Dufourt, Gérard Grisey, Tristan Murail, Jean-Claude Risset, and Kaija Saariaho. They regularly described their work, which was attuned to the transformative experiences that technologies of electronic sound production and reproduction could inspire in listeners, using metaphoric appeals to construction: to designing new sounds or exploring new illusory aural phenomena. To navigate a nascent but fast-expanding world of electronic and computer music, the spectralists appealed to physical musical attributes including gesture, space, and source-cause identification. Fascinated by gradual timbral transformations, they structured some of their pieces to invite speculative causal listening even while seeking to push it to expressive extremes. I hypothesize that, much as the immersive technology of the cinema can create the illusory feeling of flight in viewers, electronic music can inspire listeners to have experiences in excess of their physical capabilities. Those feelings are possible because listening can be understood as empathetic and embodied, drawing on a listener’s embodied and ecological sensorimotor knowledge and musical imagery alongside referential, semiotic, and cultural aspects of music. One way that listeners can engage with sounds is by imagining how they would create them: what objects would be used, what kind of gestures would they perform, how much exertion would be required, what space would they inhabit.