Reviews the Reviews Pages Are Edited by Tor Clark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download the Full Journal As A

Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume six, number one, Spring 2017 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 6 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and understanding of journalism education and of journalism, particu- larly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Mick Temple, Staffordshire University Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Deirdre O’Neill, Huddersfield University Stuart Allan, Cardiff University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, UNICEF Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, Bedfordshire University Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Irish press ombudsman (retired) Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, Brunel University Bill Reynolds, Ryerson University, Canada Ian Richards, -

Spring 2006 Bulletin 85

Advertisements Diary Dates Please refer to VLV when responding to advertisements. VLV Ltd cannot accept any liability or complaint in regard to the following offers. The charge for classified advertisements is 30p per word, 20p for Wednesday 26 April members. Please send typed copy with a cheque made payable to VLV Ltd. For display space please VLV Spring Conference contact Linda Forbes on 01474 352835. The Royal Society, London SW1 10.30am – 5.00pm The Radio Listener's Guide 2006 The Television Viewer's Guide 2006 Wednesday 26 April Presentation of VLV’s Awards G 160 pages G 160 pages for Excellence In Broadcasting G Frequencies for all BBC and commercial radio G Digital TV details of what you need to pick up Sky, The Royal Society, London SW1 stations, plus DAB digital transmitter details. Freeview or cable 1.45pm – 2.30pm G Radio Reviews Independent reviews of over G Transmitter sites for all analogue and digital Thursday, 11 May 130 radios including DAB digital radios. television transmitters. An Evening with Joan Bakewell G News from both BBC and commercial radio stations. G Equipment advice covering TV sets, VCRs, DVD One Whitehall Place, players and recorders, Sky and Freeview. G Digital Radio (DAB) The latest news and information. London SW1 G Freeview set-top box guide. 6.30pm – 8.20pm G Sky and Freeview radio information and G channel lists. Channel lists for Sky and Thursday, 18 May Freeview. VLV Evening Seminar with Mark G Advice showing how to get the G Thompson, BBC Director General best from your radio. -

Appeals to the Trust Considered by the Editorial Standards Committee

Editorial Standards Findings: Appeals to the Trust considered by the Editorial Standards Committee May 2008 Issued August 2008 Remit of the Editorial Standards Committee The Editorial Standards Committee (ESC) is responsible for assisting the Trust in securing editorial standards. It has a number of responsibilities, set out in its Terms of Reference at bbc.co.uk/bbctrust/about/meetings_and_minutes/bbc_trust_committees.html. The Committee comprises five Trustees: Richard Tait (Chairman), Chitra Bharucha, Mehmuda Mian Pritchard, David Liddiment and Alison Hastings. It is advised and supported by the Trust Unit. In line with the ESC’s responsibility for monitoring the effectiveness of handling editorial complaints by BBC management, the Committee considers appeals against the decisions and actions of the BBC’s Editorial Complaints Unit (ECU) or of a BBC Director with responsibility for the BBC’s output (if the editorial complaint falls outside the remit of the ECU). The Committee will consider appeals concerning complaints which allege that: • the complainant has suffered unfair treatment either in a transmitted programme or item, or in the process of making the programme or item • the complainant’s privacy has been unjustifiably infringed, either in a transmitted programme or item, or in the process of making the programme or item • there has otherwise been a failure to observe required editorial standards The Committee will aim to reach a final decision on an appeal within 16 weeks of receiving the request. The findings for all appeals -

The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education

Journalism Education ISSN: 2050-3903 Journalism Education The Journal of the Association for Journalism Education Volume three, Number one April 2014 Page 2 Journalism Education Volume 3 number 1 Journalism Education Journalism Education is the journal of the Association for Journalism Education, a body representing educators in HE in the UK and Ireland. The aim of the journal is to promote and develop analysis and under- standing of journalism education and of journalism, particularly when that is related to journalism education. Editors Mick Temple, Staffordshire University Chris Frost, Liverpool John Moores University Jenny McKay Sunderland University Stuart Allan, Cardiff University Reviews editor: Tor Clark, de Montfort University You can contact the editors at [email protected] Editorial Board Chris Atton, Napier University Olga Guedes Bailey, Nottingham Trent University David Baines, Newcastle University Guy Berger, Rhodes University Jane Chapman, University of Lincoln Martin Conboy, Sheffield University Ros Coward, Roehampton University Stephen Cushion, Cardiff University Susie Eisenhuth, University of Technology, Sydney Ivor Gaber, Bedfordshire University Roy Greenslade, City University Mark Hanna, Sheffield University Michael Higgins, Strathclyde University John Horgan, Irish press ombudsman. Sammye Johnson, Trinity University, San Antonio, USA Richard Keeble, University of Lincoln Mohammed el-Nawawy, Queens University of Charlotte An Duc Nguyen, Bournemouth University Sarah Niblock, Brunel University Bill Reynolds, Ryerson -

Worth 1000 Words Illustrated Reportage Makes a Comeback Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2019 Worth 1000 words Illustrated reportage makes a comeback Contents Main feature 16 Drawing the news The re-emergence of illustrated news News t’s an incredible time to be a journalist if 03 Recognition win at Vice UK you’re involved in Brexit coverage in any way. The extraordinary has become the Agreement after 3-year campaign norm and every day massive stories and 04 Barriers to women photographers twists and turns are guaranteed. Conference shares best practice IIn this edition of The Journalist, Raymond Snoddy celebrates this boom time for journalists 05 UN told of BBC persian plight and journalism in his column. And in an extract from his latest Threats to journalists’ families book, Denis MacShane looks at the role of the press in Brexit. 06 TUC news Extraordinary times also provide the perfect conditions for What the NUJ had to say and more cartoons and satirical illustration. In our cover feature Rachel Broady looks at the re-emergence of illustrated reportage, a “form of journalism that came to prominence in Victorian Features times – and arguably before that with the social commentary of 10 Payment changed my life Hogarth. The work of charity NUJ Extra A picture can indeed be worth 1,000 words. But some writers can also paint wonderfully evocative pictures with their deft 12 Fleet Street pioneers use of words. And on that note, it’s a pleasure to have Paul Women in the top jobs Routledge back in the magazine with a piece on his battle to 14 Database miners free his email address from a voracious PR database. -

'Good Evening from a Hut Near Chelmsford'

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | FEBRUARY-MARCH 2020 ‘Good evening from a hut near Chelmsford’ Modest beginnings for British broadcasting Contents Main feature 12 Radio Shack Britains first ‘wireless’ station News he media is changing so fast that 03 BBC plans major cuts few jobs stay the same and unfortunately journalists cannot Corporation to axe 450 jobs always rely on the work they know best 04 Watchdog probes magazine takeover continuing throughout their careers. Major deal under investigation TDiversifying is a way of protecting yourself against a changing landscape and we have two 05 Newsquest withdraws cuts threat features on that subject. Move follows Scottish strike vote Neil Merrick speaks to journalists who made positive starts 06 Broadcasting authority refuses to act after being made redundant or leaving local newspapers by Anger over bans on journalists setting up their own local news websites. And Ruth Addicott finds out what it takes to succeed in media training, a pursuit “which can be a lucrative and useful sideline. Features As news and journalism rapidly reshapes, it’s also interesting 14 Earning from learning to look back at much earlier innovations in the media. Jonathan Media training can be lucrative Sale traces the very early beginnings of radio which began in a small hut near Chelmsford. 16 Growth on the home turf Meanwhile there has been a key victory in the NUJ’s long- Local news sites thriving running campaign on equal pay at the BBC with the ruling by an employment tribunal that Samira Ahmed should receive Regulars pay parity with Jeremy Vine. -

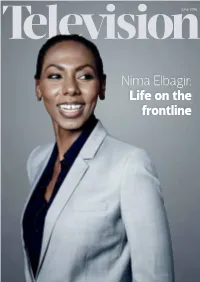

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

Louise Tickle Looks at the Prevalence of Media Organisations and Other Groups Who “Expect Journalists to Work for Nothing

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | MAY-JUNE 2018 Full Stop. Ends... Young journalists flee newspapers for PR Contents Main feature 12 Are young dreams being dashed? Why new entrants leave journalism News id you dream of becoming a reporter 03 Al Jazeera strike over pay or an editor? Many of us did, attracted by an exciting career full of variety Protest over four-year wage freeze and the potential to hold power to 04 Bid to boost women’s media presence account. Campaign taken to Scottish TUC DBut, as Ruth Addicott finds in our cover feature, many young people are deserting these roles 05 More job cuts at Trinity Mirror not long after achieving them, finding that the reality of Digital drive rolls on clickbait driven, office-bound journalism today is not what 06 NUJ Delegate Meeting 2018 they dreamt of. Conference reports And then there’s the pay…or lack of it. Louise Tickle looks at the prevalence of media organisations and other groups who “expect journalists to work for nothing. Features Since the last edition of The Journalist the NUJ has held its 10 A day in the life of biennial delegate meeting – the policy setting framework for A union communications journalist the union. Low pay, worsening conditions at the BBC, Iran’s treatment of journalists on the BBC’s Persian service and many 12 Scoop other issues were on the busy agenda in Southport. International reporting then and now There was also a motion calling for The Journalist to remain a 16 Pay day mayday print publication published at least six times a year. -

PDF File of Chapter 1

Ethics and journalism? 1 A reporter is `a man without virtue who writes lies . for his pro®t.' Dr Samuel Johnson THE REPORTING BESTIARY: WATCHDOGS, VULTURES AND GADFLYS In polls conducted in 1993 estate agents received the lowest rating in British public esteem; journalists were just above them. And yet the lure of a career in the media is stronger than ever. Reporters repel and attract; they are the twenty- ®rst century equivalent of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the `hack' for whom, in the words of foreign correspondent, Nicholas Tomalin, the only necessary quali- ®cations are `a plausible manner, rat-like cunning and a little literary ability.' Little trusted, little loved (but often secretly admired), the reporter is seen as the cynical, ruthless ®gure parodied in the Channel 4 series Drop the Dead Donkey (1990±98) and ®lms such as Broadcast News (1987) and Network (1976). Described by the satirical magazine, Private Eye, and the Royal Family as `the reptiles', compared to jackals and vultures feeding on human carrion, this image of the journalist reached its apotheosis at the time of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. The presence and behaviour of the paparazzi at the scene of the accident and Earl Spencer's public accusation that `editors have blood on their hands ± I always believed the press would kill her in the end,' was a low-water mark for British journalism. Earlier that same year, the white-suited Martin Bell, a former BBC corre- spondent, won election to Parliament as the unof®cial, anti-corruption candidate against the discredited Conservative contender, Neil Hamilton. -

Autumn 2014 Bulletin Issue 115

Working for Quality and Diversity in Broadcasting Autumn 2014 Bulletin Issue 115 THE POLITICAL DEBATE HAS BEGUN VLV’s 31st ANNUAL AUTUMN CONFERENCE These are busy times in the world of broadcasting – Public Service Broadcasting - and that means for the VLV too. reframing the debate While politicians say that formal consideration of a TUESDAY 18 NOVEMBER 2014 The Geological Society, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BG new Charter for the BBC will not start until after the General Election in May 2015, in practice the debate 10.30 am - 4.00 pm has already begun – not least in the context of the inquiry by the Select Committee for Culture, Media Much of the current debate about the future and Sport into the future of the BBC. of the BBC, Charter Review and the licence fee and broadcasting more generally seems We await its report with interest, but the omens are to us to be dominated by media, political and not particularly promising. We are concerned that industry participants, often with vested the Select Committee has spent very little time interests. The voice of the consumer, of the talking to consumers and licence fee payers and that ‘ordinary’ licence fee payer, is insufficiently a number of its members, including its Chairman, heard. Against this background the VLV seem more interested in constraining the BBC than conference will explore the issues of most in securing its future. With the current licence fee concern to viewers and listeners. agreement due to expire at the end of next year, there will be real challenges in securing adequate Sessions will include the challenges facing funding for the BBC. -

17Reporting Politics

Reporting politics 283 Reporting politics: enlightening citizens or undermining democracy? 17Darren Lilleker and Mick Temple “The press and politicians. A delicate relationship. Too close, and danger ensues. Too far apart and democracy itself cannot function without the essential exchange of information” Howard Brenton and David Hare, Pravda, Act 1, Scene 3 “Journalism is to politician as dog is to lamp-post.” H.L. Mencken, The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Quotations In recent years there have been many criticisms that politi- cal reporting has ‘dumbed down’. For some observers, political journalists increasingly concentrate on ‘personality politics’ rather than serious issues and policies (for debate, see Langer, 2011). In addition, the growth of aggressive public relations tactics by political parties attempting to control or ‘spin’ the news agenda has led to concerns that political journalists have become over-dependent on spin doctors, especially powerful governmental actors who often bully journalists into follow- ing their preferred line. Combined with concerns of overly partisan reporting, especially from print journalists, this has led to accusations that political journalism is failing in its duty to inform the public (Hargreaves & Thomas, 2002: 9). In an age when public contact with political elites is almost totally through the media, political journalists play a crucial role in liberal democracies. In order that the electorate can make ra- tional choices, journalists must deliver accurate and relatively impartial information. This chapter assesses these concerns. It begins with the rec- Reporting politics 283 ognition that a key challenge for political journalists is how to avoid becoming a megaphone for party and government propa- ganda machines – and avoid acting merely as a conduit for the ideological preferences of their employers - while still provid- ing up to date commentary on key political events of the day in a way that engages and serves their wider audience. -

1 Bbc Trust Service Licence Review Bbc Local Radio And

BBC TRUST SERVICE LICENCE REVIEW BBC LOCAL RADIO AND NEWS AND CURRENT AFFAIRS IN ENGLAND 1. Executive Summary 1.1 BBC Local Radio plays an important role in the UK’s media market. A thriving and sustainable local media sector is a vitally important part of the UK’s social, cultural and democratic landscape, and the BBC plays a key role in this through its Local Radio stations. 1.2 Local Radio is the biggest area of radio expenditure for the BBC and its content should reflect this investment. This means avoiding networked content as much as possible, playing a distinct range of music and increasing its focus on local news. Some budget reductions have been achieved in recent years, but BBC Local Radio remains adequately funded overall and there may be further scope for efficiencies in management and facilities. 1.3 The key determiner of distinctiveness for BBC Local stations remains their localness. BBC Local Radio has no distinct purpose if it does not offer a local service. England does not need another national BBC music service, nor does it need an additional national speech service. BBC Local Radio is at its best when it is a locally-focussed news and speech service, providing distinctive and high-quality speech which informs, educates and entertains. 1.4 Local Radio’s news and current affairs provision should be maintained and extended where possible in order to complement local commercial radio. ‘All speech’ programmes on BBC Local Radio should not include music, or focus on light entertainment non-news content. If it reduces or loses its speech commitments this will diminish the distinctive value it has and its unique role in the local media landscape.