Cultural Models, Landscapes, and Large Dams: an Ethnographic And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

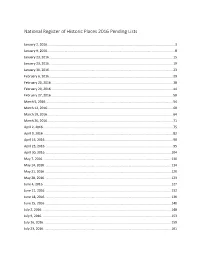

National Register of Historic Places Pending Lists for 2016

National Register of Historic Places 2016 Pending Lists January 2, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 3 January 9, 2016. ............................................................................................................................................ 8 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 15 January 23, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 19 January 30, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 23 February 6, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................ 29 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 38 February 20, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 44 February 27, 2016. ...................................................................................................................................... 50 March 5, 2016. ........................................................................................................................................... -

Santee-Cooper: a Lock on Fish Passage Success Steven Leach Normandeau Associates, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst International Conference on Engineering and International Conference on Engineering and Ecohydrology for Fish Passage Ecohydrology for Fish Passage 2012 Jun 7th, 10:50 AM - 11:10 AM Session B7 - Santee-Cooper: A Lock on Fish Passage Success Steven Leach Normandeau Associates, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fishpassage_conference Leach, Steven, "Session B7 - Santee-Cooper: A Lock on Fish Passage Success" (2012). International Conference on Engineering and Ecohydrology for Fish Passage. 5. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fishpassage_conference/2012/June7/5 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Fish Passage Community at UMass Amherst at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Engineering and Ecohydrology for Fish Passage by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Santee-Cooper: A Lock on Fish Passage A brief review of upstream passage of American shad In the Santee Cooper System, South Carolina Steve Leach Normandeau Associates, Inc. [email protected] Objective: To briefly describe the Santee Cooper, South Carolina system and outline American shad passage in the system by navigation lock and fish lock Cooper R. Santee R. History of the Santee-Cooper System • Large-scale anthropogenic perturbations • Santee Canal : 1800 -1850, first summit canal in U.S. • Santee-Cooper Project – Santee River Diversion – online 1942. Santee Dam Jefferies Station / 3,400 ft. long spillway Pinopolis Dam,130 MW 8 mi. long earthen dam rm 48 rm 89 Cooper River Fish Passage • Striped bass can live out their life cycle in freshwater1 • Santee Cooper striped bass preferentially prey on blueback herring2 • Blueback herring use the Pinopolis Lock for upstream passage3 • Since 1957, the lock has been operated in season specifically for fish passage (more on that in a couple of minutes) • But……… 1Scruggs, G.D., Jr. -

Supplemental Schedules

CLEMSON, SOUTH CAROLINA Supplemental Schedules For the Year Ended June 30, 2014 A component unit of the State of South Carolina On the cover: Tillman Hall Tillman Hall was dedicated in 1891 and was originally called “The Agricultural Building.” Much of the building was destroyed in a fire on May 22, 1894 but was rebuilt and was then known as the “Main Building.” It was formally named Tillman Hall in honor of Benjamin Ryan Tillman (Governor of South Carolina, 1890-95; United States Senator, 1895-1918; life trustee of Clemson Agricultural College, 1888-1918) by the Board of Trustees in July, 1946. Tillman Hall is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Photo by Steve Bynum, Information Tech Manager I, Customer Relations & Learning Technologies, Clemson University. Supplemental Schedules ~ 1 ~ ~ 2 ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Detailed Supplemental Statements of Financial Activity Balance Sheet - Unrestricted Current Funds .............................................................. 7 Statement of Changes in Unrestricted Net Position ................................................... 8 Statement of Unrestricted Current Fund Revenues .................................................... 10 Statement of Changes in Auxiliary Enterprises .......................................................... 13 Statement of Current Funds Revenues, Expenses and Other Changes ...................... 15 Statement of Current Fund Expenses ......................................................................... 16 Statement of Changes in Endowment and Similar -

03050201-010 (Lake Moultrie)

03050201-010 (Lake Moultrie) General Description Watershed 03050201-010 is located in Berkeley County and consists primarily of Lake Moultrie and its tributaries. The watershed occupies 87,730 acres of the Lower Coastal Plain region of South Carolina. The predominant soil types consist of an association of the Yauhannah-Yemassee-Rains- Lynchburg series. The erodibility of the soil (K) averages 0.17 and the slope of the terrain averages 1%, with a range of 0-2%. Land use/land cover in the watershed includes: 64.4% water, 21.1% forested land, 5.4% forested wetland, 4.1% urban land, 3.1% scrub/shrub land, 1.4% agricultural land, and 0.5% barren land. Lake Moultrie was created by diverting the Santee River (Lake Marion) through a 7.5 mile Diversion Canal filling a levee-sided basin and impounding it with the Pinopolis Dam. South Carolina Public Service Authority (Santee Cooper) oversees the operation of Lake Moultrie, which is used for power generation, recreation, and water supply. The 4.5 mile Tail Race Canal connects Lake Moultrie with the Cooper River near the Town of Moncks Corner, and the Rediversion Canal connects Lake Moultrie with the lower Santee River. Duck Pond Creek enters the lake on its western shore. The Tail Race Canal accepts the drainage of California Branch and the Old Santee Canal. There are a total of 43.8 stream miles and 57,535.3 acres of lake waters in this watershed, all classified FW. Additional natural resources in the watershed include the Dennis Wildlife Center near the Town of Bonneau, Sandy Beach Water Fowl Area along the northern lakeshore, the Santee National Wildlife Refuge covering the lower half of the lake, and the Old Santee Canal State Park near Monks Corner. -

Clemson University’S Facility Asaprofessional Campusserves Roadhouse, Hosting County

EDUCATION AND FESTIVALS, FAIRS, OUTDOOR AND ARTS POLITICS AND VOTING SERVICE CLUBS RESOURCES AND SERVICES ENRICHMENT AND MARKETS ENVIRONMENTAL EA IN R S E A OUNTY C ORTUNITI - BOOK RI PP T O E E TH ND A S E UID OMMUNITY ROUND A SOURC E C G ND R A WELCOME TO THE CLEMSON COMMUNITY GUIDEBOOK A PUBLICATION OF THE CITY OF CLEMSON ADMINISTRATION This Community Guidebook is intended to highlight a variety of groups, resources, and services for residents, students, and visitors in and around the Clemson area. For some, this may mean access to resources to help them through difficult times, while for others that may mean knowledge of local events and experiences to enhance their time in the area, whether for a short visit or an extended residency. Hopefully, this encourages involvement in all aspects of our community and maybe shed some light on some lesser known groups and organizations in the area. This guide includes resources and organizations in Oconee, Pickens, Anderson, and Greenville counties, which are shown in the map below. Clemson is marked by the City logo on the map, hiding in the bottom corner of Pickens County, right on the border of both Anderson and Oconee counties. (These three counties are collectively known as the Tri-County area.) Clemson is also just a short drive from Greenville, which is a larger, more metropolitan area. The City of Clemson is a university town that provides a strong sense of community and a high quality of life for its residents. University students add to its diversity and vitality. -

FORT HILL: Share in Our History. Clemson University Is Dedicated to Telling the Full and Complete History of Fort Hill — Its Triumphs and Its Tragedies

“…to convert Fort Hill into such a purpose, and thus save from desecration that beautiful hallowed spot, and pass it down for future time…” FORT HILL: Share in our history. Clemson University is dedicated to telling the full and complete history of Fort Hill — its triumphs and its tragedies. Historic Properties is charged to tell the stories of everyone, from the Native American Cherokee Nation village to the experience of the enslaved African-Americans. Thomas Green Clemson willed that Fort Hill serve “a purpose” and that the site be one of “investigation.” The National Historic Landmark has served visitors as such since its opening as a museum in 1893. With your gift, Fort Hill can continue to share the Clemson story beyond our campus boundaries and ensure that this significant property will be preserved for future educational learning projects, archaeological discoveries and generations of Clemson Tigers to come. ANNUAL GIFTS MAKE YOUR GIFT IN SUPPORT OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES GIFT DESIGNATIONS: GIFT AMOUNT Fort Hill $ ___________ Hanover House $ ___________ Hopewell $ ___________ Friends of Historic Houses $ ___________ other _________________________ $ ___________ TOTAL GIFT: $ ___________ WAYS TO GIVE → CHECK: Make check payable to Clemson University Foundation. Please insert check and this form into enclosed envelope. → CREDIT CARD: Complete the information below. VISA MasterCard American Express Discover __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ ___/___/____ _____ Credit card number Expiration date CVV Cardholder’s name (print) __________________________________________________________ Cardholder’s signature _____________________________________________________________ Maker authorizes the bank issuing the VISA, MasterCard, American Express or Discover identified on this item to pay the amount shown and promises to pay the amount stated herein to such bank subject to and in accordance with the agreement governing the use of such card. -

Santee Cooper Cross Generating Station Modeling Report

AIR MODELING REPORT Santee Cooper > Cross Generating Station 1-Hour Sulfur Dioxide NAAQS Compliance Demonstration Modeling Prepared By: J. Russell Bailey – Principal Consultant Jon Hill – Managing Consultant Allison Cole – Consultant Andrew Kessler – Consultant TRINITY CONSULTANTS 15 E. Salem Ave. Suite 201 Roanoke VA 24011 540‐342‐5945 January 2017 Project 164701.0045 Environmental solutions delivered uncommonly well TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1-1 1.1. Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1‐1 1.2. Facility Description ............................................................................................................................................... 1‐2 1.3. Location .................................................................................................................................................................... 1‐2 1.4. Nearby Facilities .................................................................................................................................................... 1‐3 2. MODEL SELECTION 2-1 3. MODELING DOMAIN 3-1 3.1. Sources to Include ................................................................................................................................................. 3‐1 Primary Sources ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

From Rice Fields to Duck Marshes: Sport Hunters and Environmental Change on the South Carolina Coast, 1890–1950 Matthew Allen Lockhart University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 From Rice Fields to Duck Marshes: Sport Hunters and Environmental Change on the South Carolina Coast, 1890–1950 Matthew Allen Lockhart University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lockhart, M. A.(2017). From Rice Fields to Duck Marshes: Sport Hunters and Environmental Change on the South Carolina Coast, 1890–1950. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4161 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM RICE FIELDS TO DUCK MARSHES: SPORT HUNTERS AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE ON THE SOUTH CAROLINA COAST, 1890–1950 by Matthew Allen Lockhart Bachelor of Arts Wofford College, 1998 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2001 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Robert R. Weyeneth, Major Professor Janet G. Hudson, Committee Member Kendrick A. Clements, Committee Member Daniel J. Vivian, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Matthew Allen Lockhart, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION In memory of my brother Marc D. Lockhart, who began this journey with me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I want acknowledge with gratitude my splendid dissertation committee. Getting to this point would not have been possible without my director, Robert R. -

2006 Report of Gifts (133 Pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society - Annual South Caroliniana Library Report of Gifts 4-29-2006 2006 Report of Gifts (133 pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation University South Caroliniana Society. (2006). "2006 Report of Gifts." Columbia, SC: The ocS iety. This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society - Annual Report of Gifts yb an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The The South Carolina South Caroliniana College Library Library 1840 1940 THE UNIVERSITY SOUTH CAROLINIANA SOCIETY SEVENTIETH ANNUAL MEETING UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Saturday, April 29, 2006 Mr. Steve Griffith, President, Presiding Reception and Exhibit .............................. 11:00 a.m. South Caroliniana Library Luncheon .......................................... 1:00 p.m. Capstone Campus Room Business Meeting Welcome Reports of the Executive Council and Secretary-Treasurer Address .................................... Dr. A.V. Huff, Jr. 2006 Report of Gifts to the South Caroliniana Library by Members of the Society Announced at the 70th Meeting of the University South Caroliniana Society (the Friends of the Library) Annual Program 29 April 2006 A Life of Public Service: Interviews with John Carl West - 2005 Keynote Address by Gordon E. Harvey Gifts of Manuscript South Caroliniana Gifts of Printed South Caroliniana Gifts of Pictorial South Caroliniana South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC) A special collection documenting all periods of South Carolina history. -

Caroliniana Society Annual Gifts Report - April 2012 University Libraries--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society - Annual South Caroliniana Library Report of Gifts 4-2012 Caroliniana Society Annual Gifts Report - April 2012 University Libraries--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, "University of South Carolina Libraries - Caroliniana Society Annual Gifts Report, April 2012". http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm/3/ This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society - Annual Report of Gifts yb an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY SOUTH CAROLINIANA SOCIETY SEVENTY-SIXTH ANNUAL MEETING __________ UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Saturday, April 28, 2012 Mr. Kenneth L. Childs, President, Presiding __________ Reception and Exhibit ..............................................................11:00 a.m. South Caroliniana Library Luncheon.....................................................................................1:00 p.m. The Palmetto Club at The Summit Club Location Business Meeting Welcome Reports of the Executive Council...................... Mr. Kenneth L. Childs Address......................................................................Dr. William A. Link Richard J. Milbauer Chair in History, University -

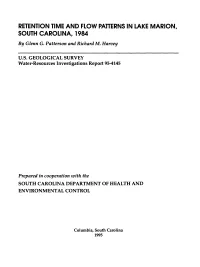

RETENTION TIME and FLOW PATTERNS in LAKE MARION, SOUTH CAROLINA, 1984 by Glenn G

RETENTION TIME AND FLOW PATTERNS IN LAKE MARION, SOUTH CAROLINA, 1984 By Glenn G. Patterson and Richard M. Harvey U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4145 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL Columbia, South Carolina 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey District Chief Earth Science Information Center U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports Section Stephenson Center- Suite 129 Box 25286, Mail Stop 517 720 Gracern Road Denver Federal Center Columbia, SC 29210-7651 Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Abstract....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose and scope........................................................................................................... 2 Description of study area................................................................................................ 2 Methods of study...................................................................................................................... 5 Retention time and flow patterns.......................................................................................... -

| City of Clemson Chapter V. CULTURAL RESOURCES ELEMENT

V. Cultural Resources ElementV-1 Chapter V. CULTURAL RESOURCES ELEMENT Chapter V. CULTURAL RESOURCES ELEMENT 1 A. HISTORY OF CLEMSON 2 B. DEFINITION OF CULTURAL RESOURCES 2 C. ARTS AND CULTURE COMMISSION 3 D. CULTURAL FACILITIES 3 E. SPECIAL EVENTS IN THE CLEMSON AREA 5 G. OTHER HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT SITES AND BUILDINGS 13 H. STATE PARKS 18 I. CLEMSON UNIVERSITY RESOURCES 20 J. CITY OF CLEMSON COMMUNITY RESOURCES 20 K. CITY OF CLEMSON POPULATION RESOURCES 21 L. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 22 M. ISSUES AND TRENDS 23 N. GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION 24 Adopted December 15, 2014 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2024 | City of Clemson V-2V. Cultural Resources Element Cultural resources are an integral part of the City of Clemson’s history and future. Cultural resources encompass everything from performing, visual, and physical arts, festivals and gatherings, special event spaces, museums and libraries, popular destinations, and historic entities – all of which make the City of Clemson an attractive and unique destination to live and play. “The Beautiful Arts- the magic bonds which unite all ages and Nations” - Thomas Green Clemson A. HISTORY OF CLEMSON The City of Clemson started as the Village of Calhoun. It was originally settled in 1872 before the establishment of Clemson University. The town developed around the railroad tracks and contributed to the agricultural growth that characterized upstate South Carolina. The Town of Calhoun was officially chartered in 1892. In 1886, Thomas Green Clemson, the son-in-law of John C. Calhoun, willed the Calhoun plantation to the State of South Carolina for a school. With classes beginning at the Clemson Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1893, the Town’s growth began to gravitate towards the institution as it provided new opportunities for the local population.