Haiti Market Analysis: Sud and Grand'anse Departments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Projects in Haiti

Haiti Assistance Program (HAP) Projects and Partnerships Project Name Implemented by Project Agreement Start Date End Date Status Description Emergency Relief Food rations for over 1 million people and associated distribution costs, primarily to young mothers and children through Contribution to Food Distribution WFP $ 29,929,039.10 19-Jan-10 31-Dec-10 Closed a partnership with the UN World Food Programme. Contributions to the IFRC Earthquake Appeal covered the purchase of tarps/tents, hygiene kits, non-food items, shipping, transportation and general infrastructure costs to mount these distributions such as purchase of vehicles and generators. The American Red Cross also donated nearly 3 million packaged meals for distribution in the early days of Domestic Heater Meals ARC $ 14,224,831.00 2010 2010 Closed the response. These funds also contributed to Base Camp set-up which was the main operational hub in Port-au-Prince in the relief and early recovery phases. Contributions to the IFRC Earthquake Appeal covered the purchase of tarps/tents, hygiene kits, non-food items, shipping, transportation and general infrastructure costs to mount these distributions such as purchase of vehicles and generators. These funds also contributed to Base Camp set-up which was the main operational hub in Port-au-Prince in Contribution to IFRC Appeal IFRC $ 6,535,937.00 2010 2012 Closed the relief and early recovery phases. Contributions to the ICRC Earthquake Appeal totaled $4,169,518, distributed across various sectors as follows: Relief $3,612,064, Shelter -

Opportunities and Challenges in the Dominican Dairy Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 5/6/2019 GAIN Report Number: DR1901 Dominican Republic Post: Santo Domingo Opportunities and Challenges in the Dominican Dairy Sector Report Categories: Dairy and Products Approved By: Lisa Ahramjian, Agricultural Attaché Prepared By: Luis C. González B, Agricultural Specialist Report Highlights: While the Dominican Republic’s (DR) dairy sector is a very important source of local employment, it is not able to supply the full range of dairy products consumed domestically, especially in the growing hotel, restaurant, and industrial (HRI) sector. In 2017, U.S. dairy exports to the DR totaled $78 million (a 27 percent market share), including cheeses and non-fat dry milk (NFDM). In 2018, U.S. dairy exports increased 11 percent ($87 million) from 2017. While the United States continues to be the dominant supplier of NFDM to the DR, it is facing increasing competition from the European Union (EU) under its Economic Partnership Agreement with CARIFORUM. The DR remains a promising sector for U.S. dairy products, including cheese, yogurt and fluid milk, given its rapidly growing economy and HRI sector. However, importers regularly face a high level of uncertainty due to stringent regulations, which are reportedly causing retailers to stop importing certain lines of dairy products. Commodities Dairy, Fluid Milk Dairy, Cheese Dairy, Skimmed Milk/NFDM Dairy, Whole Milk Powder Dairy, Malt Extract Dairy, Whey Executive Summary While the Dominican Republic’s (DR) dairy sector is a very important source of local employment, it is not able to supply the full range of dairy products consumed domestically, especially in the growing hotel, restaurant, and industrial (HRI) sector. -

Étude Sur La Santé Publique En République D'haïti

Étude sur la Santé Publique en République d’Haïti Juillet 2013 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) International Techno Center Co., Ltd. & S-Planning Inc. HM JR 13-072 Étude sur la Santé Publique en République d’Haïti Juillet 2013 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) International Techno Center Co., Ltd. & S-Planning Inc. Abréviations AFD Agence Française de Développement CAL Centre de Santé avec Lit CHU Centre Hospitalier Universitaire CSL Centre de Santé sans Lit DAB Direction de l'Administration et Budget, MSPP DELR Direction d'Épidémiologie, de Laboratoires, de Recherche, MSPP DOSS Direction d'Organisation des Service de Santé, MSPP DOTS Traitement de courte durée sous surveillance directe DRH Direction Des Ressources Humaines, MSPP DSF Direction de la Santé de la Famille, MSPP DSI Direction des Soins Infirmiers, MSPP DSNCRP Document de Stratégie Nationale pour la Croissance et pour la Réduction de la Pauvreté 2008-2010 EMMUS Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services FBP Financement basé sur la Performance HCR Hôpital Communautaire de Référence HD Hôpital Départemental HR Hôpital de Référence HUEH Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haïti MSPP Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population OMD Objectifs du millénaire pour le développement OMS Organisation mondiale de la Santé ONUSIDA Programme commun des Nations Unies sur le VIH/SIDA PARDH Plan d'Action pour le Relèvement et le Développement d'Haïti PDS Plan Directeur de Santé PNS Politique Nationale de Santé PSDH Plan Stratégique -

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake a) b) Reginald DesRoches, M.EERI, Mary Comerio, M.EERI, c) d) Marc Eberhard, M.EERI, Walter Mooney, M.EERI, a) and Glenn J. Rix, M.EERI The 12 January 2010 Mw 7.0 earthquake in the Republic of Haiti caused an estimated 300,000 deaths, displaced more than a million people, and damaged nearly half of all structures in the epicentral area. We provide an overview of the historical, seismological, geotechnical, structural, lifeline-related, and socioeco- nomic factors that contributed to the catastrophe. We also describe some of the many challenges that must be overcome to enable Haiti to recover from this event. Detailed analyses of these issues are presented in other papers in this volume. [DOI: 10.1193/1.3630129] INTRODUCTION On 12 January 2010, at 4:53 p.m. local time, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Republic of Haiti, with an epicenter located approximately 25 km south and west of the cap- ital city of Port-au-Prince. Near the epicenter of the earthquake, in the city of Le´ogaˆne, it is estimated that 80%–90% of the buildings were critically damaged or destroyed. The metro- politan Port-au-Prince region, which includes the cities of Carrefour, Pe´tion-Ville, Delmas, Tabarre, Cite Soleil, and Kenscoff, was also severely affected. According to the Govern- ment of Haiti, the earthquake left more than 316,000 dead or missing, 300,0001 injured, and over 1.3 million homeless (GOH 2010). According to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) the earthquake was the most destructive event any country has experienced in modern times when measured in terms of the number of people killed as a percentage of the country’s population (Cavallo et al. -

16 NEEDS Humani Overview

Humanitarian 16 0 2 NEEDS Overview People in Need 2.1m Dec 2015 Credit: OCHA Haiti HAITI This document is produced on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. This document provides the Humanitarian Country Team’s shared understanding of the crisis, including the most pressing humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who need assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and helps inform joint strategic response planning. The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. www.haiti.humanitarianresponse.info Part one: Summary Humanitarian needs & keyfigures Impactofthecrisis Breakdown of people in need Severity of need 03 People in need 2.1M PART I: HUMANITARIAN NEEDS Humanitarian NEEDS& KEY FIGURES The humanitarian situation in Haiti has deteriorated considerably in 2015 due to the convergence of multiple humanitarian risk factors. These include a sharp increase in food insecurity resulting from drought and the prolonged effects of “El Nino”, the persistence of cholera and a protection crisis triggered by the forced / voluntary return of thousands of Haitians from the Dominican Republic. The immediate needs of the 60,000 people who remain displaced from the 2010 earthquake cannot be overlooked. Finally, the country has a high exposure to climate hazards and natural disasters coupled with limited national response capacity. Haiti remains a largely fragile environment from a governance and development perspectives with high insecurity, overpopulation, widespread poverty, huge economic inequalit ies, a dysfunctional health system, extremely poor access to safe water and sanitation, limited agricultural production, and high environmental degradation. -

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain Fernando Rodríguez, Nora Patricia Castañeda, Mark Lundy A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti assessment Copyright © 2011 Catholic Relief Services Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Cover photo: Coffee plants in Haiti. CRS staff. Download this and other CRS publications at www.crsprogramquality.org Assessment of HAitiAn Coffee VAlue Chain A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti July 12–August 30, 2010 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms . iii 1 Executive Summary. IV 2 Introduction. 1 3 Relevance of Coffee in Haiti. 1 4 Markets . 4 5 Coffee Chain Analysis. 5 6 Constraints Analyses. 17 7 Recommendations . 19 Glossary . 22 References . 24 Annexes . 25 Annex 1: Problem Tree. 25 Annex 2: Production Solution Tree. 26 Annex 3: Postharvest Solution Tree . 27 Annex 4: Marketing Solution Tree. 28 Annex 5: Conclusions Obtained with Workshops Participants. 29 Figures Figure 1: Agricultural sector participation in total GDP. 1 Figure 2: Coffee production. 3 Figure 3: Haitian coffee exports. 4 Figure 4: Coffee chain in southern Haiti. 6 Figure 5: Potential high-quality coffee municipalities in Haiti. 9 Tables Table 1: Summary of chain constraints and strategic objectives to address them. IV Table 2: Principal coffee growing areas and their potential to produce quality coffee. 2 Table 3: Grassroots organizations and exporting regional networks. 3 Table 4: Land distribution by plot size . 10 Table 5: Coffee crop area per department in 1995 . 10 Table 6: Organizations in potential high-quality coffee municipalities. 12 Table 7: Current and potential washed coffee production in the region . -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: PIDA2769 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name HT Center and Artibonite Regional Development (P133352) Region LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Country Haiti Public Disclosure Copy Sector(s) Rural and Inter-Urban Roads and Highways (56%), Urban Transport (12%), Central government administration (10%), Public administratio n- Transportation (8%), General agriculture, fishing and forestry sector (14%) Theme(s) Rural services and infrastructure (60%), Natural disaster management (15%), Other urban development (15%), Other public sector gover nance (10%) Lending Instrument Investment Project Financing Public Disclosure Authorized Project ID P133352 Borrower(s) Ministry of Economy and Finance, MEF Implementing Agency Unite Technique d' Execution (UTE) Environmental Category B-Partial Assessment Date PID Prepared/Updated 12-Dec-2013 Date PID Approved/Disclosed 16-Jan-2014 Estimated Date of Appraisal 17-Jan-2014 Completion Estimated Date of Board 20-Mar-2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Approval Decision I. Project Context Public Disclosure Copy Country Context With a GDP per capita of US$771 in 2012, Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas. It is also one of the most unequal countries in the world (with a Gini coefficient of 0.59), lagging in social indicators (ranking 161 out of 186 in the 2013 Human Development Index). Over half its population of 10 million live on less than US$1.25 per day, and 78 percent live on less than US$2 per day. The country has been hit by multiple shocks, which have hampered economic growth and development. The repeated hurricanes, which have disproportionately large, negative impacts in Haiti, and the January 2010 earthquake are likely to have further exacerbated vulnerability. -

Hurricane Matthew Fact Sheet #3, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2017 October 9, 2016

YEMEN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #7, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 JANUARY 1, 2016 CARIBBEAN – HURRICANE MATTHEW FACT SHEET #3, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017 OCTOBER 9, 2016 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE USAID/OFDA-airlifted relief FOR THE HURRICANE MATTHEW RESPONSE IN FY 2017 supplies arrive in The Bahamas and Haiti USAID/OFDA1 $500,000 336 USAID coordinates relief operations USAID/FFP2 $1,000,000 Estimated Number of with host governments, USG Fatalities in Haiti GoH – October 8, 2016 interagency partners, and other humanitarian actors $1,500,000 UN estimates that 750,000 people in Haiti require humanitarian assistance 61,500 Estimated Number of People in Evacuation Shelters in Haiti KEY DEVELOPMENTS GoH – October 8, 2016 With support from the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), USAID Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) staff in The Bahamas conducted an initial overflight on October 7 to assess the extent of hurricane-related damage. Preliminary findings suggest that Grand Bahama 1,850 and northern Andros islands were hardest hit by the storm. Authorities have not reported Estimated Number of any fatalities in The Bahamas to date. Flooded Houses in Haiti USAID continues to coordinate with host country governments, relief actors, and U.S. OCHA – October 8, 2016 Government (USG) interagency partners—including the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—to assess the extent of hurricane-related damage, identify humanitarian needs, and mobilize response efforts 750,000 following Hurricane Matthew. Estimated Number of On October 9, the USS Mesa Verde—a U.S. Navy ship stationed off the coast of Haiti’s People in Haiti Requiring southern claw—arrived in Haiti to provide transport humanitarian supplies and personnel Humanitarian Assistance OCHA – October 8, 2016 to affected areas in southwestern portions of the country that remain largely inaccessible by road. -

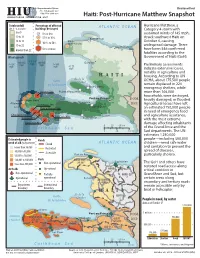

Haiti: Post-Hurricane Matthew Snapshot HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT

U.S. Department of State Unclassified [email protected] http://hiu.state.gov Haiti: Post-Hurricane Matthew Snapshot HUMANITARIAN INFORMATION UNIT Total rainfall Percentage of affected ATLANTIC OCEAN Hurricane Matthew, a Oct. 3 - 6, in inches buildings destroyed Category 4 storm with 5 to 9 5% or less sustained winds of 145 mph, 10 to 13 5.1% to 10% Port-de-Paix struck southwest Haiti on 14 to 18 Môle October 4, causing 10.1% to 50% Saint-Nicolas widespread damage. There 19 to 22 Cap Haïtien Greater than 22 50% or more have been 546 confirmed fatalities according to the Wind speeds Government of Haiti (GoH). 100-145 145-180 100-145 Gonaïves 75-100 mph mph mph 75-100 Preliminary assessments mph mph 40-75 mph indicate extensive losses, notably in agriculture and HAITI housing. According to UN Île de la OCHA, about 175,500 people Golfe Gonâve de la Gonâve remain displaced in 224 Anse à Galets emergency shelters, while Jérémie 72% Pointe à Raquettes more than 146,000 Abricots households were destroyed, Port-au-Prince Anse Dame-Marie DOM. heavily damaged, or flooded. Miragoåne d’Hainault Les Anglais 74% REP. Agricultural losses have left Les Irois Grand Goâve Port-à-Piment 88% an estimated 750,000 people in need of emergency food Chardonnière 79% Les Cayes 97% Jacmel and agriculture assistance, Coteaux 53% Côtes-de-Fer with the most extreme Port-Salut 82% damage affecting inhabitants 0 20 40 km Caribbean Sea of the Grand’Anse and the 0 20 40 mi Sud departments. The UN estimates 1,250,000 Estimated people in Roads people—including 500,000 need of aid by department Closed ATLANTIC OCEAN children—need safe water Fewer than 30,000 Restricted and sanitation to prevent the spread of diseases, 30,000 to 55,000 Accessible 55,001 to 160,000 Port-de-Paix particularly cholera. -

Automatic Exchange of Information: Status of Commitments

As of 27 September 2021 AUTOMATIC EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION (AEOI): STATUS OF COMMITMENTS1 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES IN 2017 (49) Anguilla, Argentina, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Bulgaria, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus2, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Guernsey, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Jersey, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Montserrat, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Seychelles, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turks and Caicos Islands, United Kingdom JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2018 (51) Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan3, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Curacao, Dominica4, Greenland, Grenada, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Lebanon, Macau (China), Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Monaco, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue4, Pakistan3, Panama, Qatar, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sint Maarten4, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago4, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Vanuatu JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2019 (2) Ghana3, Kuwait5 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2020 (3) Nigeria3, Oman5, Peru3 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2021 (3) Albania3, 7, Ecuador3, Kazakhstan6 -

Republic of Haiti

Coor din ates: 1 9 °00′N 7 2 °2 5 ′W Haiti Haiti (/ heɪti/ ( listen); French: Haïti [a.iti]; Haitian ˈ Republic of Haiti Creole: Ayiti [ajiti]), officially the Republic of Haiti (French: République d'Haïti; Haitian Creole: Repiblik République d'Haïti (French) [8] [note 1] Ayiti) and formerly called Hayti, is a Repiblik Ayiti (Haitian Creole) sovereign state located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican Republic.[11][12] Haiti is 27 ,7 50 square kilometres (10,7 14 sq mi) in Flag Coat of arms size and has an estimated 10.8 million people,[4] making it the most populous country in the Caribbean Motto: "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" (French)[1] Community (CARICOM) and the second-most "Libète, Egalite, Fratènite" (Haitian Creole) populous country in the Caribbean as a whole. The "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" region was originally inhabited by the indigenous Motto on traditional coat of arms: Taíno people. Spain landed on the island on 5 "L'union fait la force" (French) [2] December 1492 during the first voyage of Christopher "Inite se fòs" (Haitian Creole) Columbus across the Atlantic. When Columbus "Union makes strength" initially landed in Haiti, he had thought he had found Anthem: La Dessalinienne (French) [13] India or China. On Christmas Day 1492, Columbus' Desalinyèn (Haitian Creole) flagship the Santa Maria ran aground north of what is "The Dessalines Song" 0:00 MENU now Limonade.[14][15][16][17] As a consequence, Columbus ordered his men to salvage what they could from the ship, and he created the first European settlement in the Americas, naming it La Navidad after the day the ship was destroyed. -

Haiti – Earthquake AUGUST 18, 2021

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Haiti – Earthquake AUGUST 18, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 1,941 9,900 83,300 2.2 MILLION Earthquake-related Estimated Number of Estimated Number of People Exposed to Deaths Reported in Earthquake-related Houses Damaged or Strong—MMI Level Haiti Injuries in Haiti Destroyed VI—or Above Shaking GoH – August 2021 GoH – August 2021 UN – August 2021 USGS – August 2021 The August 14 earthquake results in at least 1,941 deaths and 9,900 injuries as of August 17, according to the GoH. DART USAR personnel and disaster experts conduct assessments and engage departmental EOCs in Grand’Anse and Sud. Earthquake-affected populations urgently require health assistance in Grand’Anse, Nippes, and Sud, where the earthquake damaged or destroyed at least 24 health facilities. Humanitarian convoys—including trucks carrying USAID/BHA-funded assistance— depart Port-au-Prince for Les Cayes. 1 TIMELINE KEY DEVELOPMENTS August 14, 2021 Earthquake Death Toll Continues to Increase Amid Acute Humanitarian Needs in Southwestern Haiti At 8:29 a.m. local time, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake The August 14 earthquake in Haiti had resulted in at least 1,941 deaths and strikes southwestern injury to more than 9,900 people as of August 17, according to the Haiti at a depth of 6.2 miles Government of Haiti (GoH). Though the majority of the casualties are in Sud Department, where the earthquake resulted in at least 1,597 deaths, August 14, 2021 Grand’Anse and Nippes department were also acutely impacted; GoH U.S. Ambassador Michele authorities reported at least 205 and 137 deaths in Grand’Anse and Nippes J.