More Than a One-Hit Wonder. Falk, Dan Astronomy. Feb2006, Vol. 34 Issue 2, P40-45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unique Sky Survey Brings New Objects Into Focus 15 June 2009

Unique sky survey brings new objects into focus 15 June 2009 human intervention. The Palomar Transient Factory is a collaboration of scientists and engineers from institutions around the world, including the California Institute of Technology (Caltech); the University of California, Berkeley, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL); Columbia University; Las Cumbres Observatory; the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel; and Oxford University. During the PTF process, the automated wide-angle 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at Caltech's Palomar Observatory scans the skies using a 100-megapixel camera. The flood of images, more than 100 gigabytes This is the Andromeda galaxy, as seen with the new every night, is then beamed off of the mountain via PTF camera on the Samuel Oschin Telescope at the High Performance Wireless Research and Palomar Observatory. This image covers 3 square Education Network¬-a high-speed microwave data degrees of sky, more than 15 times the size of the full connection to the Internet-and then to the LBNL's moon. Credit: Nugent & Poznanski (LBNL), PTF National Energy Scientific Computing Center. collaboration There, computers analyze the data and compare it to images previously obtained at Palomar. More computers using a type of artificial intelligence software sift through the results to identify the most An innovative sky survey has begun returning interesting "transient" sources-those that vary in images that will be used to detect unprecedented brightness or position. numbers of powerful cosmic explosions-called supernovae-in distant galaxies, and variable Within minutes of a candidate transient's discovery, brightness stars in our own Milky Way. -

Pluto's Long, Strange History — in Pictures : Nature News & Comment

Pluto's long, strange history — in pictures Nature marks the 85th anniversary of the dwarf planet's discovery. Alexandra Witze 18 February 2015 Even at a distance of 5 billion kilometres, Pluto has entranced scientists and the public back on Earth. Nature looks at the history of this enigmatic world, which in July will get its first close-up visit by a spacecraft. First glimpse Lowell Observatory 18 February 1930: Farmer-turned-astronomer Clyde Tombaugh (pictured), aged 24, discovers Pluto while comparing photographic plates of the night sky at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. The discovery, announced on 13 March 1930, is the culmination of observatory founder Percival Lowell’s obsessive quest to find a ‘Planet X’, the existence of which was suspected based on perturbations in Neptune’s orbit. Name game Galaxy Picture Library 1 May 1930: The Lowell Observatory announces that its favoured name for the discovery is Pluto, suggested by 11-year-old Venetia Burney (pictured) from Oxford, UK, after the Roman god of the underworld. Venetia later becomes the namesake of a student-built dust counter on NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which is currently on its way to Pluto. Pair bond US Naval Observatory 22 June 1978: James Christy and Robert Harrington, of the US Naval Observatory's Flagstaff Station, discover Pluto’s largest moon, Charon. It is visible as a bulge (at top in left image) that regularly appears and disappears in observational images as the two bodies orbit their mutual centre of gravity1. The moon is so large relative to Pluto that the two are sometimes referred to as a binary planet. -

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly - - science news articles online technology magazine articles Printer Friendly Beyond Pluto We are only beginning to discover how vast and strange our solar system truly is By Kathy A. Svitil Illustrations by Don Foley DISCOVER Vol. 25 No. 11 | November 2004 | Astronomy & Physics As a child, Mike Brown had all the trappings of an astronomer-in-the-making, with space books, rocket drawings, and a poster of the planets on his bedroom wall. On it, Pluto was depicted as “this crazy and very eccentric planet,” he says. “It was everyone’s favorite crazy planet.” Brown still recalls the mnemonic he learned for the names of the planets: Martha visits every Monday and—a for asteroids—just stays until noon, period. “The ‘period,’ for Pluto, was always suspicious,” Brown says with a laugh. “It didn’t seem to fit. So maybe that was when I first got the idea that Pluto didn’t belong.” Nowadays Brown, a planetary astronomer at Caltech, has no doubt about Pluto’s place in the solar system: “Pluto is not a planet. There is no logical reason to call Pluto a planet.” Like a growing number of his colleagues, Brown believes Pluto is best understood as the largest known member of the Kuiper belt, a band of rocky, icy miniplanets that orbit the sun in a swath stretching from beyond Neptune to a distance of nearly 5 billion miles. “I don’t think it denigrates Pluto at all to say that it is not a planet. I think Pluto is a fascinating and interesting world, and being the largest Kuiper belt object is an honorable thing to be.” No longer is Pluto a lonely outpost in an otherwise empty frontier. -

Pluto and Charon

National Aeronautics and Space Administration 0 300,000,000 900,000,000 1,500,000,000 2,100,000,000 2,700,000,000 3,300,000,000 3,900,000,000 4,500,000,000 5,100,000,000 5,700,000,000 kilometers Pluto and Charon www.nasa.gov Pluto is classified as a dwarf planet and is also a member of a Charon’s orbit around Pluto takes 6.4 Earth days, and one Pluto SIGNIFICANT DATES group of objects that orbit in a disc-like zone beyond the orbit of rotation (a Pluto day) takes 6.4 Earth days. Charon neither rises 1930 — Clyde Tombaugh discovers Pluto. Neptune called the Kuiper Belt. This distant realm is populated nor sets but “hovers” over the same spot on Pluto’s surface, 1977–1999 — Pluto’s lopsided orbit brings it slightly closer to with thousands of miniature icy worlds, which formed early in the and the same side of Charon always faces Pluto — this is called the Sun than Neptune. It will be at least 230 years before Pluto history of the solar system. These icy, rocky bodies are called tidal locking. Compared with most of the planets and moons, the moves inward of Neptune’s orbit for 20 years. Kuiper Belt objects or transneptunian objects. Pluto–Charon system is tipped on its side, like Uranus. Pluto’s 1978 — American astronomers James Christy and Robert Har- rotation is retrograde: it rotates “backwards,” from east to west Pluto’s 248-year-long elliptical orbit can take it as far as 49.3 as- rington discover Pluto’s unusually large moon, Charon. -

Spitzer to Size up Newly Found Planet

I n s i d e August 12, 2005 Volume 35 Number 16 News Briefs . 2 The story behind ‘JPL Stories’ . 3 Special Events Calendar . 2 Passings . 4 MRO launch postponed . 2 Letters, Classifieds . 4 Jet Propulsion Laborator y However, the object was so far away Spitzer that its motion was not detected until they reanalyzed the data in January of this year. In the last seven months, to size up the scientists have been studying the planet to better estimate its size and newly its motions. “It's definitely bigger than Pluto,” said found Brown, a professor of planetary astrono- my at Caltech. Scientists can infer the size of a solar planet system object by its brightness, just as one can infer the size of a faraway light bulb if one knows its wattage. The re- Artist’s concept of the flectance of the planet is not yet known. planet catalogued as Scientists cannot yet tell how much 2003UB313 at the light from the Sun is reflected away, lonely outer fringes of but the amount of light the planet re- our solar system. Later this month, the Spitzer Space Telescope flects puts a lower limit on its size. “Even if it reflected 100 percent of the light reaching it, it would Our Sun can be seen will look toward the recently discovered planet in the outlying regions of the solar system. The observation will still be as big as Pluto,” says Brown. “I'd say it’s probably one and a in the distance. bring new information on the size of the 10th planet, which lies half times the size of Pluto, but we’re not sure yet of the final size. -

PLUTO: a New Way to Explore the Planets

Q)mft version 4.1 ************************************** PLUTO: A New Way To Explore the Planets By Richard Shope and Jackie Giuliano ***** ********************************* he Pluto Fast Flyby Mission is an exciting adventure beginning (he next century with a new wuy to explore the planets, The Pluto Preproject Team at the Jet Propulsion 1,aboratory is leading the effort to design and build two spacecraft equipped with @ components atthe cutting edgeof advanced technology. ‘I’he proposed odyssey inthe first years of the ncw century will be achieved through the combined efforts of American and Russian project teams, and perhaps using Russian launch vehicles known as Protons. After seven to nine years in flight, these two innovative, cost-effective spacecraft will provide us the first ever view of the last unexplored planetary system: the mysterious planet Pluto and its enigmatic moon, Charon. The video “Ot(t of the Darkness: Mis- sion 7b Plu[o” (JPI. AVC-94- 164) provides an overview of this mission and an opportu- nity to involve your students in the challenges of such an ambitious endeavor. uL’k, vNk’k, uEu, N,k’LElkk L,uNk’Hk’L,&,k,kluE~NkL~ L’EURL, U kN vL Involve your students in ~k ku’ the thrill of discoveiy! ~ k u uk’k L,vk L’k, kQLl&kp Qlkk Llkkkl Qkklukk, ~x~, ~~ ~,~~~~~ The Pluto Fast Flyby video affords an opportunity for the teacher and student to ex- plore many concepts. These curriculum guides The cost-e ftlcient Pluto Fast Flyby spacecraft have been designed to provide the teacher at encountering Pluto and its moon Charon. -

The Big Eye Vol 2 No 1

Friends of Palomar Observatory P.O. Box 200 Palomar Mountain, CA 92060-0200 The Big Eye The Newsletter of the Friends of Palomar Observatory Vol. 2, No. 1 Solar System Now Palomar’s Astronomical Has Eight Planets Bandwidth The International Astronomical Union (IAU) recently downgraded the status of Pluto to that of a “dwarf plan- For the past three years, astronomers at the et,” a designation that will also be applied to the spheri- California Institute of Technology’s Palomar Obser- cal body discovered last year by California Institute of vatory in Southern California have been using the Technology planetary scientist Mike Brown and his col- High Performance Wireless Research and Education leagues. The decision means that only the rocky worlds Network (HPWREN) as the data transfer cyberin- of the inner solar system and the gas giants of the outer frastructure to further our understanding of the uni- system will hereafter be designated as planets. verse. Recent applications include the study of some The ruling effectively settles a year-long controversy of the most cataclysmic explosions in the universe, about whether the spherical body announced last year and the hunt for extrasolar planets, and the discovery informally named “Xena” would rise to planetary status. of our solar system’s tenth planet. The data for all Somewhat larger than Pluto, the body has been informally this research is transferred via HPWREN from the known as Xena since the formal announcement of its remote mountain observatory to college campuses discovery on July 29, 2005, by Brown and his co-discov- hundreds of miles away. -

Pluto and Its Cohorts, Which Is Not Ger Passing by and Falling in Love So Much When Compared to the with Her

INTERNATIONAL SPACE SCIENCE INSTITUTE SPATIUM Published by the Association Pro ISSI No. 33, March 2014 141348_Spatium_33_(001_016).indd 1 19.03.14 13:47 Editorial A sunny spring day. A green On 20 March 2013, Dr. Hermann meadow on the gentle slopes of Boehnhardt reported on the pre- Impressum Mount Etna and a handsome sent state of our knowledge of woman gathering flowers. A stran- Pluto and its cohorts, which is not ger passing by and falling in love so much when compared to the with her. planets in our cosmic neighbour- hood, yet impressively much in SPATIUM Next time, when she is picking view of their modest size and their Published by the flowers again, the foreigner returns gargantuan distance. In fact, ob- Association Pro ISSI on four black horses. Now, he, serving dwarf planet Pluto poses Pluto, the Roman god of the un- similar challenges to watching an derworld, carries off Proserpina to astronaut’s face on the Moon. marry her and live together in the shadowland. The heartbroken We thank Dr. Boehnhardt for his Association Pro ISSI mother Ceres insists on her return; kind permission to publishing Hallerstrasse 6, CH-3012 Bern she compromises with Pluto allow- herewith a summary of his fasci- Phone +41 (0)31 631 48 96 ing Proserpina to living under the nating talk for our Pro ISSI see light of the Sun during six months association. www.issibern.ch/pro-issi.html of a year, called summer from now for the whole Spatium series on, when the flowers bloom on the Hansjörg Schlaepfer slopes of Mount Etna, while hav- Brissago, March 2014 President ing to stay in the twilight of the Prof. -

Arizona-Based Astronomers Characterize One of the Smallest Known Asteroids

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 30 November 2016 ***Contact details appear below*** Arizona-based Astronomers Characterize One of the Smallest Known Asteroids A team of astronomers have obtained observations of the smallest asteroid –with a diameter of only two meters (six feet)—ever characterized in detail. The asteroid, named 2015 TC25, is also one of the brightest near-Earth asteroids ever discovered, reflecting 60 percent of the sunlight that falls on it. Discovered by the University of Arizona’s Catalina Sky Survey last October, 2015 TC25 was studied extensively by a team led by Vishnu Reddy, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Other participating institutions include Lowell Observatory and Northern Arizona University. The team used four Earth-based telescopes for the study, published this month in The Astronomical Journal. Reddy argues that new observations from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility and Arecibo Planetary Radar show that 2015 TC25's surface is similar to a rare type of highly reflective meteorite called aubrites. Aubrites consist of very bright minerals, mostly silicates, that formed in an oxygen-free, basaltic environment at very high temperatures. Only one out of every 1,000 meteorites that fall to Earth belong to this class. "This is the first time we have optical, infrared, and radar data on such a small asteroid, which is essentially a meteoroid," said Reddy. "You can think of it as a meteorite floating in space that hasn't hit the atmosphere and made it to the ground—yet." “2015 TC25 is one of the five smallest Near-Earth Objects ever observed to measure rotation rate” says Audrey Thirouin from Lowell Observatory. -

The Ephemeris March 2016 Volume 27 Number 01 - the Official Publication of the San Jose Astronomical Association

The Ephemeris March 2016 Volume 27 Number 01 - The Official Publication of the San Jose Astronomical Association Mar - May 2016 Events Board & General Meetings Saturday 3/19, 4/23, 5/21 Board Meetings: 6 -7:30pm General Meetings: 7:30-9:30pm Fix-It Day (2-4pm) Sunday 3/6, 4/3, 5/1 Solar Observing (locations differ) Sunday 3/6, 4/3 & Saturday 4/30 Intro to the Night Sky Class Rob Chapman and Rob Jaworski display the new SJAA banner Houge Park 1st Qtr In-Town Star Party Friday 3/11, 4/15, 5/13 Elections, Annual Awards & Pot Luck Dinner Astronomy 101 Class From Tom Piller & Rob Jaworski Houge Park 3rd Qtr In-Town Star Par- ty This year at the February 20th annual meeting, elections were held, food served, and a Friday 4/1, 4/29, 5/27 few members were recognized for making SJAA shine. It was a great meeting. Dave Ittner and Teruo Utsumi did an outstanding job of noting all that our clubs does and RCDO Starry Nights Star Party presenting the awards. Featured above is the new SJAA banner, championed by Rob Saturday 3/26, 4/30, 5/28 Jaworski, which is to be mounted permanently on the fence at Houge Park. Binocular Star Gazing Service Award recipients were: Saturday, May 28th Greg Claytor for significant contributions, participation, and service while Imaging SIG Mtg serving on the board of directors Tuesday 3/15, 4/19, 5/17 Michael Packer for significant contributions, participation, and service while serving on the board of directors Astro Imaging Workshops (at Houge Park) Marilyn Perry for being the “Bright Star” of the club Saturday 4/30, 5/28 Wolf Witt for significant participation and service in the solar program Quick STARt (by appointment) David Grover for Creation of and running of the “Intro to Night sky talks” Friday 4/8, 6/11 Glenn Newell for significant participation of numerous public outreach events Unless noted above, please refer to the SJAA Web page for specific event times Paul Colby and Marion Barker for significant participation of numerous & locations. -

Jjmonl 1706.Pmd

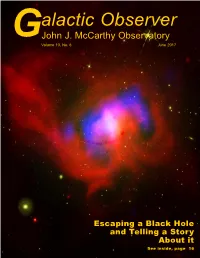

alactic Observer GJohn J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 10, No. 6 June 2017 Escaping a Black Hole and Telling a Story About it See inside, page 16 The John J. McCarthy Observatory Galactic Observer New Milford High School Editorial Committee 388 Danbury Road Managing Editor New Milford, CT 06776 Bill Cloutier Phone/Voice: (860) 210-4117 Production & Design Phone/Fax: (860) 354-1595 www.mccarthyobservatory.org Allan Ostergren Website Development JJMO Staff Marc Polansky Technical Support It is through their efforts that the McCarthy Observatory Bob Lambert has established itself as a significant educational and recreational resource within the western Connecticut Dr. Parker Moreland community. Steve Barone Jim Johnstone Colin Campbell Carly KleinStern Dennis Cartolano Bob Lambert Route Mike Chiarella Roger Moore Jeff Chodak Parker Moreland, PhD Bill Cloutier Allan Ostergren Doug Delisle Marc Polansky Cecilia Detrich Joe Privitera Dirk Feather Monty Robson Randy Fender Don Ross Louise Gagnon Gene Schilling John Gebauer Katie Shusdock Elaine Green Paul Woodell Tina Hartzell Amy Ziffer In This Issue OUT THE WINDOW ON YOUR LEFT .................................... 4 SUMMER NIGHTS ........................................................... 12 MARE NECTARIS AND BOHNENBERGER CRATER .................. 4 ASTRONOMICAL AND HISTORICAL EVENTS ......................... 12 FIRST ENCOUNTER .......................................................... 5 REFERENCES ON DISTANCES ............................................ 15 OPPORTUNITY RETROSPECTIVE ........................................ -

ASSA Bulletin August 2017

The Volume 126 No. 8 August 2017 Bullen Monthly newsleer of the Astronomical Society of South Australia Inc In this issue: ♦ ASSA 125th Anniversary Dinner a great success ♦ Discoveries during ASSA’s 5th decade ♦ Mary’s first trip to the Alpana AstroCamp ♦ A dark night out with the serpent VicSouth bookings now open. www.vicsouth.info/ 2017.htm Registered by Australia Post Visit us on the web: Bullen of the ASSA Inc 1 August 2017 Print Post Approved PP 100000605 www.assa.org.au In this issue: ASSA Acvies 3-4 Details of general meengs, viewing nights etc History 5-7 ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY of Astronomical discoveries during ASSA 5th decade SOUTH AUSTRALIA Inc Alpana Astrocamp 8-9 GPO Box 199, Adelaide SA 5001 Mary Marnias tells of her first Alpana AstroCamp The Society (ASSA) can be contacted by post to the Astro News 10 address above, or by e-mail to [email protected]. Latest astronomical discoveries and reports Membership of the Society is open to all, with the only prerequisite being an interest in Astronomy. The Sky this month 11-14 Solar System, Comets, Variable Stars, Deep Sky Membership fees are: Full Member $75 ASSA Contact Informaon 15 Concessional Member $60 Subscribe e-Bullen only; discount $20 Members’ Image Gallery 16 Concession informaon and membership brochures can A gallery of members’ astrophotos be obtained from the ASSA web site at: hp://www.assa.org.au or by contacng The Secretary (see contacts page). Member Submissions Sister Society relaonships with: Submissions for inclusion in The Bullen are welcome Orange County Astronomers from all members; submissions may be held over for later edions.