Modern Electric Time Service. 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science: Magnetic Effect of Electric Current: Electric Bell and Generator- Flexiprep

9/22/2021 Science: Magnetic Effect of Electric Current: Electric Bell and Generator- FlexiPrep FlexiPrep Science: Magnetic Effect of Electric Current: Electric Bell and Generator (For CBSE, ICSE, IAS, NET, NRA 2022) Doorsteptutor material for ICSE/Class-10 is prepared by world's top subject experts: get questions, notes, tests, video lectures and more- for all subjects of ICSE/Class-10. Electric Bell This electrical device where electromagnetic is used as components. In electric bell ‘U’ shaped electromagnet is used. This is also called horseshoe electromagnet. Soft iron is placed between the arms of this electromagnet. This is called as ‘core’ . 1 of 4 9/22/2021 Science: Magnetic Effect of Electric Current: Electric Bell and Generator- FlexiPrep ©FlexiPrep. Report ©violations @https://tips.fbi.gov/ Force on a Current Carrying Conductor in a Magnetic Field When a conductor carrying a current is placed in a magnetic field, the conductor experiences a magnetic force. The direction of this force is always right angles to the plane containing both the conductor and the magnetic field and is predicted by Fleming՚s Left-Hand Rule. 2 of 4 9/22/2021 Science: Magnetic Effect of Electric Current: Electric Bell and Generator- FlexiPrep ©FlexiPrep. Report ©violations @https://tips.fbi.gov/ Referring to the diagram above, F is Force, B is Magnetic field, I is current. Factors Affecting Magnetic Force on a Current-Carrying Conductor in a Magnetic Field Strength of the magnetic field Current flowing through the wire Length of the wire , where F is force acting on a current carrying conductor , B is magnetic flux density (magnetic field strength) , is magnitude of current flowing through the conductor, is length of conductor, is angle that conductor makes with the magnetic field. -

Teaching Electricity and Magnetism Through the Radio

November, 1926] THE VIRGINIA TEACHER 267 have victrola records for pronunciation. TEACHING ELECTRICITY Two of these nine think they are invaluable AND MAGNETISM in teaching high school pupils. Thirty of the teachers subscribe to some French peri- THROUGH THE odical, Le Petit Journal, Lectures Pour RADIO Tous, La Presse, Modern Language Jour- IN THIS age most children have come nal, or L'Illustration. in contact with radio and are more or The French teachers of the state, besides less-interested in it. Every good teach- teaching French, have many duties. One of er wishes to present her subject through the these is the sponsoring of French clubs. medium of everyday experiences. Radio Very few, however, have the pleasure of offers such a medium for the study of elec- doing this—only fourteen of the sixty- tricity and magnetism (a different topic to seven. Among the names given to these present in textbook fashion). clubs are La Bonne Heure, Le Cercle Fran- It is a simple matter through a class dis- (ais, Songs and Recitations, Modern Lan- cussion of radio sets to get from the pupils guage Club, La Societe Frangaise, and The a suggestion that they be allowed to make French Circle. The majority of the teachers one. At this time the teacher should point devote only two periods of the day to out the difficulty of the problem and sug- French, and therefore they must teach other gest that the pupils decide what principles of subjects. The fact that seventy-four per electricity and magnetism are necessary for cent of these other subjects are languages, understanding and constructing a radio either English, Latin or Spanish, is very in- set. -

![Electricity Merit Badge Pamphlet 35886.P[...]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8283/electricity-merit-badge-pamphlet-35886-p-3728283.webp)

Electricity Merit Badge Pamphlet 35886.P[...]

BOy ScOUtS OF AMERICA MERIT BADGE SERIES ElEctricity Requirements 1. Demonstrate that you know how to respond to electrical emergencies by doing the following: a. Show how to rescue a person touching a live wire in the home. b. Show how to render first aid to a person who is unconscious from electrical shock. c. Show how to treat an electrical burn. d. Explain what to do in an electrical storm. e. Explain what to do in the event of an electrical fire. 2. Complete an electrical home safety inspection of your home, using the checklist found in this pamphlet or one approved by your counselor. Discuss what you find with your counselor. 3. Make a simple electromagnet and use it to show magnetic attraction and repulsion. 4. Explain the difference between direct current and alternating current. 5. Make a simple drawing to show how a battery and an electric bell work. 6. Explain why a fuse blows or a circuit breaker trips. Tell how to find a blown fuse or tripped circuit breaker in your home. Show how to safely reset the circuit breaker. 7. Explain what overloading an electric circuit means. Tell what you have done to make sure your home circuits are not overloaded. 35886 ISBN 978-0-8395-3408-2 ©2004 Boy Scouts of America BANG/Brainerd, MN 2010 Printing 1-2010/059230 8. On a floor plan of a room in your home, make a wiring diagram of the lights, switches, and outlets. Show which fuse or circuit breaker protects each one. 9. Do the following: a. -

Physical Science ELECTRIC CURRENT and ITS EFFECTS I

VAIRAMS MATRIC.HR.SEC.SCHOOL-PUDUKKOTTAI CLASS: VII LESSON-14 SUB: Physical Science ELECTRIC CURRENT AND ITS EFFECTS I. Multiple choice Questions: A) Select the correct option. 1. A coil refers to __________ a) an electric wire b) a fuse c) a current carrying conductor d) a wire twisted in the form of a circle 2. The effect of current on which the working of a fuse is based is _______________ a) magnetic effect b) chemical effect c) heating effect d) induction effect 3. A filament of low melting point metal/alloy is used in ___________ a) electric bulb b) electric iron c) heating effect d) electric fuse 4. A circuit diagram is _________ a) a picture of a circuit b) a drawing of a circuit with standard pictures for the different electrical components. c) a drawing of an electrical circuit with standard symbols for the different electrical components d) a difficult representation of an electric circuit. 5. In an electric bell, we have ___________ a) an electromagnet b) an interrupter c) a hammer d) all of these 6. An electric fuse is __________ a) a safety device b) an appliance c) used to produce electricity d) used to heat a room 7. An electromagnet acts like a magnet _________ a) When a current is passed through the coil. b) all the time c) because it has a magnetic core d) only if a current does not pass through the coil. 8. An electric fuse wire melts if the amount of current flowing through it is a) more than a minimum amount b) less than a minimum amount c) more than a maximum amount d) less than a maximum amount B. -

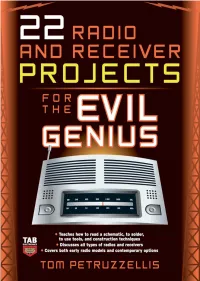

22 Radio Receiver Projects for the Evil Genius Evil Genius Series

22 Radio Receiver Projects for the Evil Genius Evil Genius Series Bionics for the Evil Genius: 25 Build-it-Yourself Projects Electronic Circuits for the Evil Genius: 57 Lessons with Projects Electronic Gadgets for the Evil Genius: 28 Build-it-Yourself Projects Electronic Games for the Evil Genius Electronic Sensors for the Evil Genius: 54 Electrifying Projects 50 Awesome Auto Projects for the Evil Genius 50 Model Rocket Projects for the Evil Genius Mechatronics for the Evil Genius: 25 Build-it-Yourself Projects MORE Electronic Gadgets for the Evil Genius: 40 NEW Build-it-Yourself Projects 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius 123 PIC® Microcontroller Experiments for the Evil Genius 123 Robotics Experiments for the Evil Genius PC Mods for the Evil Genius Solar Energy Projects for the Evil Genius 25 Home Automation Projects for the Evil Genius 51 High-Tech Practical Jokes for the Evil Genius 22 Radio Receiver Projects for the Evil Genius TOM PETRUZZELLIS New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2008 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159475-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148929-0. -

Electric Bells and Alarms

H OW TO I N STALL El tric Bells Annunciators ec , , and Alar s m . lN CLUD lN G rie s Wire s a n d Wir in C irc u its P us/z e s Be lls Ba tte , g, , , , Bu r la r A la r m s H i lz a rid L o w Wa te r A l r m s g , g a , A n u n cia Fire A l a rms , Tit e r m o s ta ts , n to rs , and til e L oca tio n a n d Re m e dying T o u ble s of r . ' N O RM AN H SCH N EI DER . ‘ ' “ A uth o r o f Th e St u d o f Ele ct ricit fo r e in n e rs C are and y y B g , " H an dlin o f El e ct ric Plant s e t c g , . , e t c . SECON Q fidmomfism m ééb N EW YO RK SPON CH AMBERLA N 123 LIBER I . TY STREET LON DO N E F . N P . S O N . Limite d 57 AYMARKE W , H T. S . 1913 Co pyrigh t 1904 C o pyrigh t 1913 By SPON 8c CHAMBERLAIN The C ame o t Pre ss 16- 18 Oak St N e w l , PREFACE Amo ng all the applications of electric ity to d m mm s s fe w w o estic or co ercial u e , are as ide P c spread as the electric bell . -

Electric Bell: When You Push the Switch, the Current Flows in the Coil

Physics 7: Magnetism & electromagnetism Section 3: Uses of electromagnets Section 1: Permanent Magnets & Electromagnets Key term Definition Permanent magnet A magnet that is magnetic all the time, e.g. a bar magnet or a horseshoe magnet or a fridge magnet Electromagnet A magnet that can be turned on and off. Needs an electric current in a coil (called a solenoid) to work Magnetic field An area around a magnet where a magnetic material will be attracted Magnetic field lines These show the shape of a magnetic field. You can Relay switch: A small current in the coil show magnetic field lines with iron filings. turns it into an electromagnet. The iron Electric bell: When you push the armature is attracted to the Magnetic material A material that is attracted to a magnet: iron, Scrapyard electromagnet: switch, the current flows in the electromagnet and pivots to push the steel, cobalt & nickel Electromagnets can be made much coil of wire, the electromagnet switch contacts closed. This turns on a Section 2: Magnetic Fields stronger than permanent magnets turns on and attracts the iron separate circuit that can have a much and they can be switched on and off. armature. The hammer hits the We can show magnetic larger current. Used in electronic In a scrapyard, an electromagnet gong and the contact switch fields by placing paper devices and car ignition circuits. picks up scrap metals that contain opens. This stops the current and over a magnet and iron or steel and does not pick up any the electromagnet turns off. The sprinkling iron filings on other metals. -

Electromagnets

45 Electromagnets ● Oersted’s discovery ● Electromagnets ● Field due to a straight wire ● Electric bell ● Field due to a circular coil ● Relay, reed switch and circuit breaker ● Field due to a solenoid ● Telephone ● Magnetisation and demagnetisation ● Practical work: Simple electromagnet ●● Oersted’s discovery ●● Field due to a straight In 1819 Oersted accidentally discovered the wire magnetic effect of an electric current. His experiment can be repeated by holding a wire If a straight vertical wire passes through the centre of over and parallel to a compass needle that is a piece of card held horizontally and there is a current pointing N and S (Figure 45.1). The needle moves in the wire (Figure 45.2), iron fi lings sprinkled on when the current is switched on. Reversing the the card settle in concentric circles when the card is current causes the needle to move in the opposite gently tapped. direction. Evidently around a wire carrying a current there is a magnetic fi eld. As with the fi eld due right-handed to a permanent magnet, we represent the fi eld screw shows field due to a current by fi eld lines or lines of force. plotting direction Arrows on the lines show the direction of compass the fi eld, i.e. the direction in which a N pole points. field lines Different fi eld patterns are given by differently shown by iron shaped conductors. filings card current direction straight current wire direction S compass needle Figure 45.2 Field due to a straight wire N movement of needle Plotting compasses placed on the card settle along the fi eld lines and show the direction of the fi eld at different points. -

Design and Development of Microcontroller Based Solar Powered College Bell

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(4): 1326-1333 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 04 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.804.154 Design and Development of Microcontroller based Solar Powered College Bell Ramesh Harajibhai Chaudhari1, Bhagyalaxmi R. Rajgor1, V.M. Modi1, Vinay Patel1, Dhaval Chaudhari1 and Alok Gora2* 1College of Renewable Energy & Environmental Engineering, 2C.P. College of Agriculture SDAU, Sardarkrushinagar, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT K e yw or ds The world over the decades has made considerable advancement in automation; it is employed in homes, industries, commercial and educational sectors. In present work, a Automation, solar power-operated microcontroller-based automatic college bell is designed and Microcontroller, developed. For the harmonic tuning, converted normal college bell into automatic college Rely, Real Time bell and powered by solar PV system with battery backup. It uses electrical coil for Clock, Electrical generating the EMF for striking the clapper on the edge of a bell for making sound. It uses Coil, Solar PV System, Clapper, the Real Time Clock (DS1307) which tracks the real time. The microcontroller (ATMEGA 328p) is used to control all the functions; it gets the time through the keypad and stores it Keypad in its memory. When programmed time equals the real time then the bell is switched on via Article Info a relay for a predetermined time. The bell ringing time can be edited at any time so that it can be reused again and again at normal class timings as well as at exam times.