Gavin Anderson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Do Not Forget This" Cause, but We Were Sustained and by Dr

i. d. a.! news notes Published by the United States Committee of the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa P.O. Box 17, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 December, 1982 Telephone (617) 491-8343 CANON JOHN COLLINS concerned about apartheid. He was particularly interested in America, for here he sensed a growing consciousness of the evils of 1905-1982 apartheid and a desire to do what can be done to support those The death of the Reverend Canon L. John Collins on December who oppose it. This faith in America caused him to establish our 30, 1982 in the 78th year of his age has brought to a close a great American Committee and to support it to this day. His clerical life of creative service for God and the world; and we, associated colleagues thought him egotistical, intolerant, and a bit fuzzy on with the work of the International Defense and Aid Fund for the niCeties of doctrine. His secular critics thought him "soft" on Southern Africa, have been deprived of our founder, President, the "hard" issues of our times. But there are countless sons and and guiding force. That there is a Defense and Aid Fund today daughters of Africa, exiled or imprisoned, who weep at word of and an ever growing world-wide consciousness of the evils of his death, for they know that in John Collins they have lost an apartheid is due to the Christian outrage, organizational skills, incomparable friend and advocate. I join them in their sense of loss and personal charisma of John Collins. -

Bill Freund 1944 -2020 Donkey Back in Ios, 1966 Tomato Harvesting in Zaria, 1978 Boston 1982

Bill Freund 1944 -2020 Donkey back in Ios, 1966 Tomato harvesting in Zaria, 1978 Boston 1982 Boston 1981 Chris Saunders I first met Bill in Cape Town in the late 1960s when he was researching the Batavian period at the Cape for his Ph.D. When he heard I was returning to Oxford by sea, he asked me to take the material he had collected in Cape Town with him – this was of course long before the age of computers! - as he wanted to travel back to Europe overland. Having assembled a vast quantity of material for my own thesis, I was astonished when he produced one open shoebox in which were a set of notecards. Until I returned the shoebox to him in Oxford some weeks later, I was aware that if anything happened to it his Ph.D would probably never be completed. When I handed the shoebox back, he did joke that it seemed there were fewer notecards than he remembered. How he wrote a Ph.D based on those notecards remains a mystery, but Bill was of course a superb historian, with a great gift for synthesis, and the way he reinvented himself over the decades, exploring so many diverse and difficult topics, should inspire those of us who remain in narrow research ruts. Now I remember him most for his friendship on three continents, which included putting us up in Cambridge, Mass., Leamington and Durban, and, on one especially memorable occasion, taking us to spend some days at Champagne Castle… Thanks, dear Bill; Go Well… Francie Lund Dearest colleague and friend Bill: I will miss you so much, as mentor, with your hugely comprehensive knowledge and your generosity with shared learning; I will miss your being in Davine's and my home at Christmas time and at parties; I will miss your stories about the places you go to, and your own family history(ies). -

Neil Aggett Papers

BC 1110 NEIL AGGETT PAPERS Donated to the University of Cape Town Libraries by Mr J A E and Mrs J N Aggett 1997; amended 2007 and 2008 ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Biographical note iii The Collection iv A. PERSONAL 1 B. CORRESPONDENCE 1 C. THE INQUEST 2 D. NEWSCLIPPINGS 3 E. VARIOUS REPORTS AND ARTICLES 3 F. DETAINEES PARENTS SUPPORT COMMITTEE (DPSC) 4 G. MEDIA COVERAGE 4 H. TRUTH & RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) 4 J. PHOTOGRAPHS 4 K. MISCELLANEOUS 5 Additional material: received 2006. L. LETTERS TO AND FROM MRS JOYCE AGGETT 5 M. TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) 5 N. RECORDS RELATING TO DEATH AND DETENTION OF NEIL AGGETT 5 P. ATTEMPTS TO OBTAIN ACCESS TO SECURITY FILES 5 Q. VARIOUS 6 Additional material: received 2008 R LETTERS TO HIS PARENTS 6 iii INTRODUCTION BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Neil Aggett was born on 6 October 1953 in Nanyuki, Kenya. At the age of 10 he immigrated to South Africa with his family. He attended school at Kingswood College in Grahamstown from where he matriculated with a 1st class pass and a distinction in Maths. He went on to study Medicine at the University of Cape Town. He did his internship at hospitals in Umtata (Transkei) and Tembisa in the Transvaal. It was here that he became aware that his patients’ medical problems stemmed mostly from “social problems such as poverty, unemployment and poor living conditions.” On completion of his internship he worked at Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. During this time he also did part-time work for the Industrial Aid Society helping workers with Workman’s Compensation problems, as many of the patients he treated were injured at work. -

The Controversy Over US Companies in South Africa

Two Decades of Debate: the controversy over U.S. companies in South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.bmdv2 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Two Decades of Debate: the controversy over U.S. companies in South Africa Author/Creator Hauck, David; Voorhes, Meg; Goldberg, Glenn Publisher Investor Responsibility Research Center, Inc Date 1983-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) United States, South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1960-1982 Rights By kind permission of the Investor Responsibility Research Center, and with thanks to Glenn S. Goldberg. Description This review of the debate on U.S. -

Neil Aggett: a Man of the People

PINS, 2016, 50, 105 – 107, http://dx.doi.org.10.17159/2309-8708/2016/n50a7 Neil Aggett: A man of the people [BOOK REVIEW] John Reynolds1 Neil Aggett Labour Naidoo, Beverley (2012) Death of an Studies Unit, idealist: In search of Neil Aggett. Rhodes University, Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball. Grahamstown ISBN 978-1-86842-520-4 pbk. Pages xix + 475 Beverley Naidoo’s Death of an idealist: In search of Neil Aggett is an extraordinary achievement. She brings to life the complex dynamics that shaped this remarkable South African, and gives us a rich portrait not only of him as a multi-faceted and changing human being, but also of the social and political environment in which his short life was lived. She evokes the time in which Dr Neil Hudson Aggett lived in all its complexity, sketching vividly not only the horrors of the apartheid system and its security apparatuses, but also the complex socialisation of people living within that system. In her richly detailed account of Neil’s life, she illustrates the possibility of agency even in the most repressive of systems, and traces his development in dynamic interaction with his context. Neil Aggett transcended his background to embody the ideal of a just, non-racial and non-sexist democratic South Africa. His privileged school education and his training as a medical doctor did not predetermine the trajectory of his life, but rather provided a context within which he engaged with ideas and with others around him. He opened himself to other people in a manner that changed him and them in unpredictable ways and that had social consequences beyond anything he could have imagined. -

Michigan Office Opens SWAPO and the West

Published by the United States Committee of the International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa P.O. Box 17, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 April, 1982 Telephone (617) 491-8343 prisoners in Southern Africa and aid their dependents until that time Michigan Office Opens when apartheid has been dismantled and civilized values restored. by Kenneth Carstens, Executive Director, IDAF·USA We express our most grateful thanks for the dedicated and unstinting efforts of the splendid band of deeply committed men and women who are members orsupporters ofthe Michigan Committee. A senior reporter and photographer from the Oeh'oil Free Press and crews from three television stations were on hand to cover the opening of the Michigan office of IDAF - our first regional office. The media conducted three extensive interviews with me, and reporters showed considerable interest in the conditions in Southern SWAPO and the West Africa that make the existence of lOAF a moral necessity: the Draconian laws that imprison innocent men, women and children An interview with Eric Biwa without charge, subject them to inhuman and degrading torture, and The following interview with Eric Biwa, Deputy Secretary for have already resulted in 56 known deaths - all in the defense of Economic Affairs of SWAPO, is an edited version of one conducted white supremacy. It was encouraging to encounter journalists who on March 31 by Colin Leis, a reporterfor WHRB radio in Cambridge, were both alert and politically responsible. Mass. Mr. Biwa was in Boston seeking support for UN Resolution Although, as Executive Director, I had the privilege of opening the 435, which calls for free elections in Namibia and an end to South office and holding a press conference to mark the event, the Africa's illegal occupation, which Mr. -

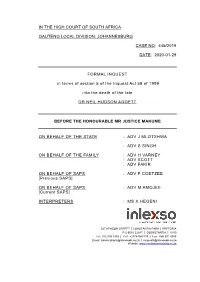

High Court of South Africa

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA GAUTENG LOCAL DIVISION, JOHANNESBURG CASE NO: 445/2019 DATE: 2020-01-29 FORMAL INQUEST in terms of section 5 of the Inquest Act 58 of 1999 into the death of the late DR NEIL HUDSON AGGETT BEFORE THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE MAKUME ON BEHALF OF THE STATE : ADV J MLOTSHWA : ADV S SINGH ON BEHALF OF THE FAMILY : ADV H VARNEY : ADV SCOTT : ADV FAKIR ON BEHALF OF SAPS : ADV F COETZEE [Previous SAPS] ON BEHALF OF SAPS : ADV M AMOJEE [Current SAPS] INTERPRETERS : MS X HEGENI 537 KENSON STREET | CONSTANTIA PARK | PRETORIA P.O BOX 32917 | GLENSTANTIA | 0100 Tel : 012 993 1335 | Cell: +27784987479 | Fax : 086 601 5996 Email: [email protected] | [email protected] Website: www.veritastranscribing.co.za 1 RECORD PROCEEDINGS ON 29 JANUARY 2020 [09:28] COURT CLERK: Now it is the matter of the Inquest of the late Doctor Neil Hudson Aggett, case number 445/2019. COURT: Thank you. Yes, before we, we proceed, you recall that yesterday I had indicated my unavailability for tomorrow afternoon from two o’clock. The position has changed, I am now available, the program has been re-arranged, so please, you can do your arrangements as if I am available for tomorrow in the afternoon. I will cancel. 10 MR VARNEY: Noted sir, duly, thank you. COURT: Thank you. MR VARNEY: M'Lord, before we commence with our witness for today, I have undertaken to keep the Court appraised as to our efforts in tracing the balance of the first Inquest record. -

Remembering Heroes on the 'Fringe'

THE JOURNAL OF THE HELEN SUZMAN FOUNDATION | ISSUE 71 | NOVEMBER 2013 BOOK REVIEW Remembering Heroes on the ‘Fringe’ Dr Anthony Egan, a Catholic Choosing to be Free: The Life Story of Rick priest and Jesuit, is a member of the Jesuit Turner by Billy Kenniston Institute – South Africa in Johannesburg. He is Research Fellow Death of an Idealist: In search of Neil at the Helen Suzman Foundation. Trained Aggett by Beverley Naidoo in history and politics at UCT (MA) and Wits A sign of the resilience of South African historiography, often in the (PhD) he is also a moral theologian, who face of attempts to create (consciously or unconsciously) a new ‘patriotic’ has lectured at Wits consensus, is the fact that we still find the publication of what might be University (Political called marginal narratives, accounts of fringe movements, minority Studies), St John Vianney Seminary groups and biographies of relatively minor characters in our history. The (moral theology) and publication of two new biographies – of the philosopher-activist Richard St Augustine College Turner and the trade unionist Dr Neil Aggett – highlights this important of South Africa (moral theology and tendency, which has, I shall argue, significance beyond the discipline of applied ethics). He is history extending towards positive new South African democratic self- completing a book on just war theory. perceptions. Both Richard Turner (known to all his friends as Rick) and Neil Aggett share certain common features: they were white activists in the anti-apartheid struggle who cannot easily be fitted into any political tradition; they were both very young when they died (Turner was 36, Aggett 28) in ‘unusual’ circumstances almost certainly at the hands, directly or indirectly, of the State ( Turner was assassinated in 1978 near the end of his five-year banning order1; Aggett probably committed suicide while detained without trial in 19812). -

& Your Newspaper, FREE of CHARGE

Your newspaper, FREE OF CHARGE Care for your mental health Pages 2, 4 and 7 Graeme cricket on form Page 16 5 October 2018 • Vol. 148 Issue: 038 Live in Makhanda Out with the old... in with the new! ‘Come to the s[h]ow’ is what the faded George Street welcome sign seems to say. Nombasa Maqoko (centre) holds up the poster advertising ‘Divas: a night to celebrate legends’ in a one-night-only concert in the Guy Butler Theatre featuring Nombasa, Zahara and Msaki, along with the Kwantu Choir. Read more on page 8. Their last performances here were in Grahamstown. Tonight they will perform in Makhanda, following Minister of Arts and Culture Nathi Mthethwa final pronouncement this week. With Nombasa here are concert organisers Sisanda Mankayi and Kate Davies of the National Arts Festival. And yes – the three Creative City welcome signs are set for a makeover: watch this space! Photo: Sue Maclennan FACELIFT & HAVE ARRIVED GRAHAMSTOWN 046 622 3914 STEVEN 078 113 3497 JOHAN 082 566 1046 TRYING TO CUT COSTS WITH GLASS TEL: 046 622 2950 TEL: 046 622 8700 TIM 082 800 9276 IS LIKE DRIVING WITHOUT YOUR SEATBELT ON KEVIN 082 772 0400 2 NEWS Grocott’s Mail 5 OCTOBER 2018 Joza Clinic now open on weekends By SUE MACLENNAN DRIVEN BY PEOPLE rom 1 October 2018, the Joza POWERED BY TECHNOLOGY Clinic has extended its opening hours. As well as Monday to Fri- Securing Fday, the clinic will now be open on t h e c i t y f o r o v e r Saturdays, Sundays and public holi- 25 years days, 8am to 4.30pm, Ward 2 coun- cillor Ramie Xonxa said negotiations SAFETY with the Department of Health over several months had followed a plea TIPS from the clinic committee on behalf of the public for easier access to med- FROM ical help over the weekends. -

The Dean with Sax Appeal What an MBA Taught Me the Prickly Pear

Rhodos The Dean with 22Sax Appeal What an MBA 21Taught Me The Prickly 43Pear Economy Prof Santy Daya, Dean of Pharmacy A PUBLICATION OF THE COMMUNICATIONS AND ADVANCEMENT DIVISION OF RHODES UNIVERSITY VOLUME 13 | NOVEMBER 2017 Publisher Fundraising 1 R1-billion in 10 years. That’s the goal of the Isivivane Fund Rhodes University Dr Sizwe Mabizela 2 The Vice-Chancellor puts his money where his mouth is Thank you to all the Alumni 4 departments and Radio host and author Eusebius McKaiser remembers dancing on the tables at The Vic; Tanya Accone is making her mark at Unicef; and Mbuso Mtshali, Rich Mkhondo, Sarah Wild and Garth Elzerman talk about their time at Rhodes individuals who contributed to this publication Life in res 9 Where good friendships are made and everything is close by Drama 12 A product of the The magic and mastery of Professor Gary Gordon Communications and Zoology 14 Advancement Division How zebras are making horses sick Neil Aggett Labour Studies Unit 15 Email: MA student Siviwe Mhlana thinks grassroots about globalisation [email protected] Biotechnology 16 Imagine using a cellphone app to get the results of a pregnancy or HIV test. That’s exactly what the Rhodes University Biotechnology Innovation Centre has done Tel: 046 603 8570 Farewell to the Registrar 19 Dr Stephen Fourie leaves Rhodes after 26 years with a wealth of memories Business School 20 Address: Dr Tshidi Mohapeloa believes entrepreneurship cannot be taught, only practised; and a Rhodes MBA changed Rhodes University the way Mudiwa Gavaza sees the role of business Alumni House Pharmacy 22 Santy Daya wasn’t allowed to attend Rhodes because he was classified as black. -

The Death of Neil Aggett: Unions and Politics, Then and Now

THE DEATH OF NEIL AGGETT: UNIONS AND POLITICS, THEN AND NOW Edward Webster Second Annual Neil Aggett Labour Studies Lecture Rhodes University, 21 September 2015 On the morning of 27th November 1981 Neil Aggett was arrested in Johannesburg and taken to John Vorster Square. Seventy days later, 5th February 1982, he was dead. He was 28 years old. He was the first white person to die in detention. It is a great honour to deliver the Second Annual Neil Aggett Labour Studies lecture. Why did Dr Neil Aggett, a medical doctor and organiser for the Food and Canning Workers Union, die in detention? In her brilliant biography, Death of an Idealist: In Search of Neil Aggett, Beverley Naidoo suggests two scenarios.1 Scenario One: Neil is murdered by his torturers in his cell and his body is then strung up to make it appear as suicide. Scenario Two: He decides to take his own life. He had been under constant observation and interrogation for nearly seven weeks. He had been brought to the depths of despondency. But, in writing his first statement on 8th January, he had defied them. In the weeks that followed they broke him down, physically and mentally, but he was going to allow them no more satisfaction. He had worked out how to hang himself and he went about it dispassionately, as if he was preparing to operate on a patient. In his final hours he is wrestling back dominion over himself and who he is. He can, concludes Naidoo, accept philosophically his own death, whereas he could never have reconciled himself with being Whitehead’s – his torturers’ - pawn (Naidoo, 2012: 286). -

T He Africa' N T He Africa' N Communist N095 FOURTH

T he Africa' n T he Africa' n Communist N095 FOURTH QUARTER 1983 .5 . .. ... ... INKULULEKO PUBLICATIONS Distributors of The African Communist SUBSCRIPTION PRICE AFRICA £2. 00 per year including postage £7.50 airmail per year (Readers in Nigeria can subscribe by sending 4 Naira to New Horizon Publications, p.o. Box 2165. Mushin Lagos. o, t(, KPS Bookshop. PMB 1023, Afikpo, Irno State.) BRITAIN £3. 00 per year including postage NORTH AMERICA ALL OTHER COUNTRIES $8. 00 per year including postage $15. 00 airmail per year £3. 00 per year including postage £7.50 airmail per year INKULULEKO PUBLICATIONS, 38 Goodge Street, London WlP 1FD ISSN 0001-9976 Proprietor: Moses Mabhida Phototypesetting and artwork by Carlinpoint Ltd. (T.U.) 5 Dryden Street, London WC2 Printed by Interdruck Leipzig No 95 Fourth Quarter 1983 CONTENTS 5 Editorial Notes Hands off the Frontline Statesl; For Land. Bread and Peace; U.S. Marx Centenary Conference. Moses Mabhida 16 Marx Belongs To Everyone Paper delivered to a conference to commemorate the centenary of the death of Karl Marx held in New York last March under the auspices of Political Affairs, the theoretical journal of the Communist Party of the USA. R.S. Nyameko 27 Workers' Militancy Demands Trade Union United Front The upsurge by workers on the trade union front means that every effort must be made to form a united trade union federation if the maximum opposition is to be mobilised against the apartheid regime. A Special Correspondent 37 Frelimo Fights for the Future of Mozambique The fourth congress of the Frelimo Party in Maputo last April-was an historic event not only for the Mozambican people but for all the progressive and revolutionary forces in Southern Africa.