In Urban Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maureen Duff - Casting Director PO Box 47340, London NW3 4TY Tel: 020 7586 0532 Fax: 020 7681 7172 Mob: 07967 022 721

1 Maureen Duff - Casting Director PO Box 47340, London NW3 4TY Tel: 020 7586 0532 Fax: 020 7681 7172 Mob: 07967 022 721 Casting CV MA Eng. & Phil., University of Glasgow. Member of BAFTA, Bectu and the Casting Directors’ Guild. Advanced Script Readers Course, Script Factory. As Casting Director: Feature Films Director/Producer Closing The Ring (2006) Dir: Richard Attenborough (UK/Irish casting) Prod: Jo Gilbert & Richard Attenborough The Flying Scotsman Dir: Douglas Mackinnon, Prod: Peter Broughan X-Mass (2005) – short film Dir: Scott Flockhart, Prod: Jonathan Hayes (won British Council Student Film Award at Dinard Film Festival 2005) The Pink Panther – UK search for footballers! Dir: Shawn Levy, Prods: Toby Jaffe, Ivan Reitman, Tom Pollock, Robert Simonds Running Scared – UK casting Dir: Wayne Kramer, prod Co: Media 8 Ent. (US) Prods: Mark Damon, Michael A Pierce One of the Hollywood Ten Dir: Karl Francis/Prod: Juan Gordon/Moreno Films (Joint Casting with Gail Stevens) – see also Casting Associate film credits Colour Me Kubrick (Casting Associate) Dir; Brian Cook, Prods: B. Cook/Michael Fitzgerald Millions (Casting Associate) Dir: Danny Boyle, Prod: Graham Broadbent 28 Days Later (Casting Associate) Dir: Danny Boyle, Prod: Andrew Macdonald/ Figment Films/Fox The Beach (Casting Associate) Dir: Danny Boyle/ Prod: Andrew Macdonald Figment Films/Fox Calendar Girls (Casting Associate) Dir: Nigel Cole/Prods: Nick Barton, Suzanne Mackie, Steve Clark Hall/Buena Vista Television Company Director/Producer Fatal Passage – (Joint UK Casting with Polly Hootkins) PTV Prods, Canada Dir: John Walker, Prod. Andrea Nemtin H20 II - Trojan Horse – UK Casting Whizbang Films Inc. Dir: Charles Biname (Canadian mini-series) Prod: Frank Siracusa, Exec. -

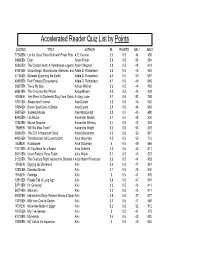

Accelerated Reader Quiz List by Points

Accelerated Reader Quiz List by Points QUIZNO TITLE AUTHOR BL POINTS ABL1 ABL2 77268EN Let the Good Times Roll with Pirate Pete aA.E. Cannon 2.6 0.5 44 453 36996EN Deer Aaron Frisch 5.8 0.5 54 894 25862EN The Crystal Heart: A Vietnamese Legend Aaron Shepard 3.8 0.5 48 618 61081EN Groundhogs: Woodchucks, Marmots, and Adele D. Richardson 3.2 0.5 46 535 51184EN Minerals (Exploring the Earth) Adele D. Richardson 4.3 0.5 50 687 43998EN Rain Forests (Ecosystems) Adele D. Richardson 4.1 0.5 49 660 28837EN Twice My Size Adrian Mitchell 2.6 0.5 44 453 68561EN The Crow and the Pitcher Aesop/Brown 2.5 0.5 44 439 6300EN Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China Ai-Ling Louie 5.1 0.5 52 798 77074EN Always and Forever Alan Durant 3.2 0.5 46 535 78584EN Brown Bear Gets in Shape Alan Durant 2.6 0.5 44 453 56876EN Scaredy Mouse Alan MacDonald 2.8 0.5 45 480 80400EN Lila Bloom Alexander Stadler 3.7 0.5 48 604 17540EN Mouse Surprise Alexandra Whitney 2.4 0.5 43 425 7598EN Will We Miss Them? Alexandra Wright 5.3 0.5 53 825 20660EN The Gift: A Hanukkah Story Aliana Brodmann 4.3 0.5 50 687 44054EN The Mountain that Loved a Bird Alice McLerran 4.5 0.5 50 715 5539EN Roxaboxen Alice McLerran 4 0.5 49 646 77073EN All You Need for a Beach Alice Schertle 2.3 0.5 43 411 30316EN Uncle Farley's False Teeth Alice Walsh 3.1 0.5 46 522 21232EN The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel wAlice/Martin Provensen 2.6 0.5 44 453 9763EN Digging Up Dinosaurs Aliki 3.6 0.5 47 591 13804EN Dinosaur Bones Aliki 3.7 0.5 48 604 9765EN Feelings Aliki 2 0.5 41 370 13815EN Fossils Tell of -

![[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5636/ghanabib-1819-1979-prepared-23-11-2011-ghanabib-1980-1999-prepared-30-12-2011-ghanabib-2000-2005-prepared-03-03-6245636.webp)

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 Prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 Prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 Prepared 03/03

[Ghanabib 1819 – 1979 prepared 23/11/2011] [Ghanabib 1980 – 1999 prepared 30/12/2011] [Ghanabib 2000 – 2005 prepared 03/03/2012] [Ghanabib 2006 – 2009 prepared 09/03/2012] GHANAIAN THEATRE A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES A WORK IN PROGRESS BY JAMES GIBBS File Ghana. Composite on ‘Ghana’ 08/01/08 Nolisment Publications 2006 edition The Barn, Aberhowy, Llangynidr Powys NP8 1LR, UK 9 ISBN 1-899990-01-1 The study of their own ancient as well as modern history has been shamefully neglected by educated inhabitants of the Gold Coast. John Mensah Sarbah, Fanti National Constitution. London, 1906, 71. This document is a response to a need perceived while teaching in the School of Performing Arts, University of Ghana, during 1994. In addition to primary material and articles on the theatre in Ghana, it lists reviews of Ghanaian play-texts and itemizes documents relating to the Ghanaian theatre held in my own collection. I have also included references to material on the evolution of the literary culture in Ghana, and to anthropological studies. The whole reflects an awareness of some of the different ways in which ‘theatre’ has been defined over the decades, and of the energies that have been expended in creating archives and check-lists dedicated to the sister of arts of music and dance. It works, with an ‘inclusive’ bent, on an area that focuses on theatre, drama and performance studies. When I began the task I found existing bibliographical work, for example that of Margaret D. Patten in relation to Ghanaian Imaginative Writing in English, immensely useful, but it only covered part of the area of interest. -

The Ship of Death' to the Story of Murder on Screen, Expansion Of'ofosu Ystory' Was and Lottery Winner

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. HE current con- trasts on British TV are strik- ing. Rhodes, twelve years in the making, ten episodes, nu- merous shorts that include hundreds of impis or miners, turn of the century South Af- rica and Lobengula's kraal lovingly reconstructed, two books as major spin off s, and a budget, according to the British press, of £10 million. Deadly Voyage, based on events that led to a trial in Rouen during December 1995, a one and a half hour'film for Saturday even ing TV,' with some early crowd scenes and thereafter a small - indeed a diminishing - cast locked in a ship, made on a budget, it seems, of £4 million. reviewer observes how the Screenplay, DEADLY outstanding) are rising stars with their own VOYAGE Shown on BBC 1 Deadly Voyage re- ceived the kind of publicity and attention from growing bands of followers - and, I am sure, fared on reviewers that its price-tag demanded. One their own razor-sharp agents. British can guess where part of the money went. The Guardian claimed to have broken television Some of the cast are pretty costly: Joss the story of the Ghanaian stowaways mur- and in Ackland's whisky captain can't have come dered by Ukrainian sailors on the MS Ruby the cheap, and from his Vlachos, a sort of Greek and tossed into the sea off Portugal during Poirot, David Suchet must have named a high 1992. -

Director of Photography

JAN PESTER DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FEATURE FILM and TV DRAMA CREDITS: Title Director Producer THE WICKER TREE Robin Hardy Peter Snell (Red 4k for 35mm) Feature Film Peter Watson-Wood Thriller/Fantastique from Alastair Gourlay director of original Wicker Man British Lion Films Brittania Nicol Henry Garrett Sir Christopher Lee Graham McTavish Honeysuckle Weeks Clive Russell DINOSAPIEN David Winning, Rick Siggelkow, (HDcam) 15X30’ Live/Animation Dean Bennett, Jim Corston, family series Brendan Sheppard, Jayne Schipper, (EMMY NOMINEE Pat Williams Jordy Randall. OUTSTANDING CCI Entertainment for ACHIEVEMENT IN SINGLE Discovery and BBC CAMERA PHOTOGRAPHY 2008) Brittney Wilson James Coombes TERRY PRATCHETT’S Vadim Jean Rod Brown, HOGFATHER (snow unit) Ian Sharples (35mm/Arri D20) 4hr TV Mob Films for Sky TV Live/Animation/CGI Christmas Show BAFTA NOMINEE BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY 2007) David Jason Ian Richardson Michelle Dockery Joss Ackland WILD COUNTRY Craig Strachan Ros Borland (HDcam for 35mm) Feature Film- Gabriel Films Horror (WINNER BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY-Estepona Film Festival 2006) Martin Compston Peter Capaldi SHOEBOX ZOO series 2 Justin Molotnikov, Claire Mundell (HDcam) 13X30’ Live/Animation Dean Bennett Christine Shipton family series Francis Damberger Noreen Halpern Gordon Tootoosis Grant Harvey Tom Cox Peter Mullan Jordy Randall Jason Connery BBC/Blueprint Entertainment Canada SHOEBOX ZOO series 1 Justin Molotnikov Claire Mundell (HDcam) 13X30’ Live/Animation James Henry Christine Shipton family series Noreen Halpern (BAFTA WINNER Best -

An Overview of the Film, Television, Video and Dvd Industries In

the STATS an overview of the film, television, video and DVD industries 1990 - 2003 contents THIS PDF IS FULLY NAVIGABLE BY USING THE “BOOKMARKS” FACILITY IN ADOBE ACROBAT READER Introduction by David Sharp . i Introduction to 1st edition (2003) by Ray Templeton . .ii Preface by Philip Wickham . .iii the STATS 1990 . .1 1991 . .14 1992 . 32 1993 . 54 1994 . .74 1995 . .92 1996 . .112 1997 . .136 1998 . .163 1999 . .188 2000 . .220 2001 . .251 2002 . .282 2003 . .310 Cumulative Tables . .341 Country Codes . .351 Bibliography . .352 Research: Erinna Mettler/Philip Wickham Design/Tabulation: Ian O’Sullivan Additional Research: Matt Ker Elena Marcarini Bibliography: Elena Marcarini © 2006 BFI INFORMATION SERVICES BFI NATIONAL LIBRARY 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN ISBN: 1-84457-017-7 Phil Wickham is an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the BFI National Library. He writes and lectures extensively on British film and television. Erinna Mettler is an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the National Library and has contributed to numerous publications. Ian O’Sullivan is also an Information Officer in the Information Services Unit of the BFI National Library and has designed a number of publications for the BFI. Information Services BFI National Library British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Tel: + 44 (0) 20 7255 1444 Fax: + 44 (0) 20 7436 0165 Contact us at www.bfi.org.uk/ask with your film and television enquiries. Alternatively, telephone +44 (0) 20 7255 1444 and ask for Information (Mon-Fri: 10am-1pm & 2-5pm) Try the BFI website for film and television information 24 hours a day, 52 weeks a year… Film & TV Info – www.bfi.org.uk/filmtvinfo - contains a range of information to help find answers to your queries. -

HOWARD BURDEN - Costume Designer

HOWARD BURDEN - Costume Designer YOUNG WALLANDER Director: Ole Endresen. Producers: Berna Levin and Luke Franklin. Starring: Adam Pålsson, Joe Layton, Lucy Akhurst and Leanne Best. Yellow Bird / Netflix. WORZEL GUMMIDGE Director: Mackenzie Crook. Producer: Georgie Fallon. Starring: Mackenzie Crook. Leopard Pictures. DAD’S ARMY: THE LOST EPISODES Director: Ben Kellett. Producer: Candida Julian-Jones. Starring: Kevin McNally, Robert Bathurst and Bernard Cribbins. Mercury Productions. POLDARK (Series 5) Director: Sallie Aprahamian. Producer: Michael Ray. Starring: Aidan Turner and Eleanor Tomlinson. Mammoth Screen. WORZEL GUMMIDGE (Pilot) Director: Mackenzie Crook. Producer: Louise Sutton. Leopard Pictures. ZAPPED! (Series 3) Director: Dave Lambert. Producer: Kerry Waddell. Starring: James Buckley, Louis Emerick and Sharon Rooney. Baby Cow Productions. WAR OF THE WORLDS Director: Craig Viveiros. Producer: Betsan Morris Evans. Starring: Eleanor Tomlinson and Jonathan Aris. Mammoth Screen. POLDARK (Series 4) Directors: Joss Agnew and Brian Kelly. Producer: Michael Ray. Starring: Aidan Turner and Eleanor Tomlinson. Mammoth Screen. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] ZAPPED! (Series 2) Director: Dave Lambert. Producer: Kerry Waddell. Starring: James Buckley, Paul Kaye, Louis Emerick and Sharon Rooney. Baby Cow Productions. RTS Craft and Design Awards Nomination 2018 – Best Costume Design POLDARK (Series 3) Directors: Stephen Woolfenden and Joss Agnew. Producers: Roopesh Parekh and Michael Ray. Starring: Aidan Turner and Eleanor Tomlinson. Mammoth Screen. ZAPPED! Director: Dave Lambert. Producer: Kerry Waddell. Starring: Paul Kaye, James Buckley, Louis Emerick and Sharon Rooney. Baby Cow Productions. RED DWARF (Series 11 & 12) Director: Doug Naylor. Producers: Richard Naylor and Kerry Waddell. -

March 8, 2011 (XXII:8) John Mackenzie, the LONG GOOD FRIDAY (1980, 114 Min)

March 8, 2011 (XXII:8) John Mackenzie, THE LONG GOOD FRIDAY (1980, 114 min) Directed by John Mackenzie Written by Barrie Keeffe Produced by Barry Hanson Cinematography by Phil Meheux Edited by Michael Taylor Music Composed by Francis Monkman Paul Freeman...Colin Leo Dolan...Phil P.H. Moriarty...Razors Derek Thompson...Jeff Bryan Marshall...Harris Bob Hoskins...Harold Shand Helen Mirren...Victoria Charles Cork...Eric Pierce Brosnan...1st Irishman Eddie Constantine...Charlie Stephen Davies...Tony PAUL FREEMAN...Colin (January 18, 1943, Barnet, JOHN MACKENZIE (August 16, 1932, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) Hertfordshire, England, UK) has appeared in 102 films and TV has 27 directing credits, including 2009 “The Wright Stuff,” series and films, some of which are 2010 “MI-5,” 2010 2003 Quicksand, 2000 When the Sky Falls, 1998 “Aldrich Ames: Centurion, 2009 “Lark Rise to Candleford,” 2008 “Agatha Traitor Within,” 1993 “Voyage,” 1990 The Last of the Finest, Christie's Poirot,” 2006-2007 “New Street Law,” 2004 George 1987 The Fourth Protocol, 1985 The Innocent, 1983 Beyond the and the Dragon, 2002-2003 “Monarch of the Glen,” 2002 Haker, Limit, 1980 The Long Good Friday, 1973-1979 “Play for 2000 “Inspector Morse,” 2000 The 3 Kings, 1995 “The Final Today,” 1979 A Sense of Freedom, 1973 “Country Matters,” Cut,” 1995 The Horseman on the Roof, 1995 Mighty Morphin 1972 Made, 1970 “W. Somerset Maugham,” 1970 One Brief Power Rangers: The Movie, 1992-1993 “The Young Indiana Summer, 1968 “The Jazz Age,” and 1966-1967 “Thirty-Minute Jones Chronicles,” 1990 Eminent -

Democracy and Choice: Do These Mean Anything to the Average Ghanaian?

Advances in Applied Sociology, 2017, 7, 115-135 http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci ISSN Online: 2165-4336 ISSN Print: 2165-4328 Democracy and Choice: Do These Mean Anything to the Average Ghanaian? Ishmael Norman1,2,3 1School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Hohoe Campus, Ho, Ghana 2Institute for Security, Disaster and Emergency Studies, Sandpiper Place, Langma, Ghana 3African Academy for Environmental Health (AAEH), University of Malawi, Zomba, Malawi How to cite this paper: Norman, I. (2017). Abstract Democracy and Choice: Do These Mean Anything to the Average Ghanaian? Ad- The concept of “African democracy” invokes James and Stuart Rachels’ (2003) vances in Applied Sociology, 7, 115-135. treatise against “Cultural Relativism”. That is to say, it is generally assumed https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2017.73007 that there is democracy relative to Africa and therefore, there is a concept of Received: January 14, 2017 “African Democracy Relativism”. Due to this, democracy in Africa oughts to Accepted: March 28, 2017 be different from democracy everywhere else. “Choice” as an ethical value Published: March 31, 2017 subsists and emanates from autonomy and freedom. When people are free in the democracy, they also have the freedom of “choice” in their functionings. Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. There are many limitations on the right to choose in Africa due to the general This work is licensed under the Creative limitations placed on freedoms. This paper proposes that there is but one type Commons Attribution International of democracy in the world, which offers individuals the same kind of freedom License (CC BY 4.0).