Japanese Guideline for Adult Asthma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amlexanox TBK1 & Ikke Inhibitor Catalog # Inh-Amx

Amlexanox TBK1 & IKKe inhibitor Catalog # inh-amx For research use only Version # 15I29-MM PRODUCT INFORMATION METHODS Contents: Preparation of 10 mg/ml (33.5 mM) stock solution • 50 mg Amlexanox 1- Weigh 10 mg of Amlexanox Storage and stability: 2- Add 1 ml of DMSO to 10 mg Amlexanox. Mix by vortexing. - Amlexanox is provided lyophilized and shipped at room temperature. 3- Prepare further dilutions using endotoxin-free water. Store at -20 °C. Lyophilized Amlexanox is stable for at least 2 years when properly stored. Working concentration: 1-300 μg/ml for cell culture assays - Upon resuspension, prepare aliquots of Amlexanox and store at -20 °C. Resuspended Amlexanox is stable for 6 months when properly stored. TBK1/IKKe inhibition: Quality control: Amlexanox can be used to assess the role of TBK1/IKKe using cellular - Purity ≥97% (UHPLC) assays, as described below in B16-Blue™ ISG cells. - The inhibitory activity of this product has been validated using cellular 1- Prepare a B16-Blue™ ISG cell suspension at ~500,000 cells/ml. assays. 2- Add 160 µl of cell suspension (~75,000 cells) per well. - The absence of bacterial contamination (e.g. lipoproteins and 3- Add 20 µl of Amlexanox 30-300 µg/ml (final concentration) and endotoxins) has been confirmed using HEK-Blue™ TLR2 and HEK-Blue™ incubate at 37 °C for 1 hour. TLR4 cells. 4-Add 20 µl of sample per well of a flat-bottom 96-well plate. Note: We recommend using a positive control such as 5’ppp-dsRNA delivered intracellularly with LyoVec™ . DESCRIPTION 5- Incubate the plate at 37 °C in a 5% CO incubator for 18-24 hours. -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

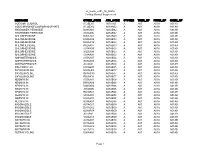

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Fatty Liver Disease (Nafld/Nash)

CAYMANCURRENTS ISSUE 31 | WINTER 2019 FATTY LIVER DISEASE (NAFLD/NASH) Targeting Insulin Resistance for the Metabolic Homeostasis Targets Treatment of NASH Page 6 Page 1 Special Feature Inside: Tools to Study NAFLD/NASH A guide to PPAR function and structure Page 3 Pathophysiology of NAFLD Infographic Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Apoptosis Targets Page 5 Page 11 1180 EAST ELLSWORTH ROAD · ANN ARBOR, MI 48108 · (800) 364-9897 · WWW.CAYMANCHEM.COM Targeting Insulin Resistance for the Treatment of NASH Kyle S. McCommis, Ph.D. Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO The obesity epidemic has resulted in a dramatic escalation Defects in fat secretion do not appear to be a driver of in the number of individuals with hepatic fat accumulation hepatic steatosis, as NAFLD subjects display greater VLDL or steatosis. When not combined with excessive alcohol secretion both basally and after “suppression” by insulin.5 consumption, the broad term for this spectrum of disease Fatty acid β-oxidation is decreased in animal models and is referred to as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). humans with NAFLD/NASH.6-8 A significant proportion of individuals with simple steatosis will progress to the severe form of the disease known as ↑ Hyperinsulinemia Insulin resistance non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), involving hepatocyte Hyperglycemia damage, inflammation, and fibrosis. If left untreated, Adipose lipolysis NASH can lead to more severe forms of liver disease such Steatosis as cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver failure, and De novo O ↑ lipogenesis HO eventually necessitate liver transplantation. Due to this large clinical burden, research efforts have greatly expanded Fatty acids to better understand NAFLD pathogenesis and the mechanisms underlying the transition to NASH. -

Emerging Drug List AMLEXANOX

Emerging Drug List AMLEXANOX NO. 1 APRIL 2001 Trade Name (Generic): Amlexanox ( Apthera®) Manufacturer: Access Pharmaceuticals, Inc. / Paladin Labs Inc. Indication: For the treatment of aphthous ulcers (canker sores). Current Regulatory Amlexanox paste is currently marketed in the United States under the trademark Status (in Canada Apthasol™ and is also available in Japan in a tablet formulation for the treatment of and abroad): asthma. A Notice of Compliance was received from the Therapeutic Products Programme on December 11th, 2000. Paladin Labs Inc. would be the distributor of this product in Canada and they expect to launch the product early in the year 2001. Description: At this time, the exact mechanism of action by which amlexanox causes accelerated healing of aphthous ulcers is unknown. Amlexanox, an antiallergic agent, is a potent inhibitor of the formation and/or release of inflammatory mediators from cells including neutrophils and mast cells. As soon as a canker sore is discovered, a small amount of paste (i.e., 0.5 cm) is applied four times daily to each ulcer. Treatment is continued until the ulcer is healed. Should no significant healing or pain relief be apparent after 10 days of use, medical or dental advice should be sought. Apthera® is expected to be available as a 5% paste formulation in Canada. Current Treatment: Treating aphthous ulcers can be accomplished via topical and oral interventions. Medications are aimed at reducing secondary infection, controlling pain, reducing the duration of lesion presence, and possibly preventing recurrence. There have been numerous medications studied in the treatment of the lesions, both systemic and topical. -

Drug Formulary Effective October 1, 2021

Kaiser Permanente Hawaii QUEST Integration Drug Formulary Effective October 1, 2021 Kaiser Permanente Hawaii uses a drug formulary to ensure that the most appropriate and effective prescription drugs are available to you. The formulary is a list of drugs that have been approved by our Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee. Committee members include pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and other allied health care professionals. Our drug formulary allows us to select drugs that are safe, effective, and a good value for you. We review our formulary regularly so that we can add new drugs and remove drugs that can be replaced by newer, more effective drugs. The formulary also helps us restrict drugs that can be toxic or otherwise dangerous if. Our drug formulary is considered a closed formulary, which means that drugs on the list are usually covered under the prescription drug benefit, if you have one. However, drugs on our formulary may not be automatically covered under your prescription benefit because these benefits vary depending on your plan. Please check with your Kaiser Permanente pharmacist when you have questions about whether a drug is on our formulary or if there are any restrictions or limitations to obtaining a drug. NON-FORMULARY DRUGS Non-formulary drugs are those that are not included on our drug formulary. These include new drugs that haven’t been reviewed yet; drugs that our clinicians and pharmacists have decided to leave off the formulary, or a different strength or dosage of a formulary drug that we don’t stock in our Kaiser Permanente pharmacies. Even though non-formulary drugs are generally not covered under our prescription drug benefit options, your Kaiser Permanente doctor can request a non-formulary drug for you when formulary alternatives have failed and the non-formulary drug is medically necessary, provided the drug is not excluded under the prescription drug benefit. -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 Bezwada (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US008O26285B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,026,285 B2 BeZWada (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 27, 2011 (54) CONTROL RELEASE OF BIOLOGICALLY 6,955,827 B2 10/2005 Barabolak ACTIVE COMPOUNDS FROM 2002/0028229 A1 3/2002 Lezdey 2002fO169275 A1 11/2002 Matsuda MULT-ARMED OLGOMERS 2003/O158598 A1 8, 2003 Ashton et al. 2003/0216307 A1 11/2003 Kohn (75) Inventor: Rao S. Bezwada, Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2003/0232091 A1 12/2003 Shefer 2004/0096476 A1 5, 2004 Uhrich (73) Assignee: Bezwada Biomedical, LLC, 2004/01 17007 A1 6/2004 Whitbourne 2004/O185250 A1 9, 2004 John Hillsborough, NJ (US) 2005/0048121 A1 3, 2005 East 2005/OO74493 A1 4/2005 Mehta (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2005/OO953OO A1 5/2005 Wynn patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2005, 0112171 A1 5/2005 Tang U.S.C. 154(b) by 423 days. 2005/O152958 A1 7/2005 Cordes 2005/0238689 A1 10/2005 Carpenter 2006, OO13851 A1 1/2006 Giroux (21) Appl. No.: 12/203,761 2006/0091034 A1 5, 2006 Scalzo 2006/0172983 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada (22) Filed: Sep. 3, 2008 2006,0188547 A1 8, 2006 Bezwada 2007,025 1831 A1 11/2007 Kaczur (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2009/0076174 A1 Mar. 19, 2009 EP OO99.177 1, 1984 EP 146.0089 9, 2004 Related U.S. Application Data WO WO9638528 12/1996 WO WO 2004/008101 1, 2004 (60) Provisional application No. 60/969,787, filed on Sep. WO WO 2006/052790 5, 2006 4, 2007. -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Research Article

RESEARCH ARTICLE The efficacy of amlexanox and triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of recurrent aphthous ulcers. Satish Balwani Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Dr. Rajesh Ramdasji Kambe Dental College and Hospital, Akola, Maharashtra, India. Abstract Background: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is the most common oral mucosal disease characterised by chronic, ulcerative condition of the oral mucosa. Material and Methods: In this study we compared the efficacy of 5% Amlexanox with 0.1% Triamcinolone Acetonide in patients with RAS for pain relief and healing time. The patients were principally divided into 2 study groups, 30 in each group. Group A were treated by 5% Amlexanox, and Group B were given 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide, topical application on the ulcer 3 times a day for 7 days. Results: The mean value of pain scores on the days after the treatment from the first day to the seventh day was significantly higher in amlexanox group than triamcinolone acetonide group (푃 ≤ 0.05). The time of complete healing of ulcers was recorded in amlexanox group, the mean healing time of ulcers, reported by these 24 patients, was 4.17 ± 1.80 days (range 4-7). In triamcinolone acetonide group, the mean healing time of ulcers, reported by 30 patients with healed ulcers, was 2.24 ± 1.36 days (range 2-4). The difference was statistically significant (푃 ≤ 0.05). Conclusion: Both amlexanox and triamcinolone acetonide are effective and safe in the treatment of aphthous ulcers. Key words: Recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Amlexanox, triamcinolone acetonide, oral ulcer. term and later it was described by Mikulicz and Kummel as ‘Mikulicz’s aphthae.’ It is Introduction more common in patients between 10-40 Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) years of age.2 is the most common oral mucosal disease RAS is classified into 3 types, minor, characterised by chronic, ulcerative major, and herpetiform aphthous ulcerations condition of the oral mucosa without a fully according to the diameter of the lesion. -

Mast Cell Involvement in Fibrosis in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Mast Cell Involvement in Fibrosis in Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease Ethan Strattan and Gerhard Carl Hildebrandt * Division of Hematology and Blood & Marrow Transplant, Markey Cancer Center, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40536, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is most commonly a treatment for inborn defects of hematopoiesis or acute leukemias. Widespread use of HSCT, a potentially curative therapy, is hampered by onset of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), classified as either acute or chronic GVHD. While the pathology of acute GVHD is better understood, factors driving GVHD at the cellular and molecular level are less clear. Mast cells are an arm of the immune system that are known for atopic disease. However, studies have demonstrated that they can play important roles in tissue homeostasis and wound healing, and mast cell dysregulation can lead to fibrotic disease. Interestingly, in chronic GVHD, aberrant wound healing mechanisms lead to pathological fibrosis, but the cellular etiology driving this is not well-understood, although some studies have implicated mast cells. Given this novel role, we here review the literature for studies of mast cell involvement in the context of chronic GVHD. While there are few publications on this topic, the papers excellently characterized a niche for mast cells in chronic GVHD. These findings may be extended to other fibrosing diseases in order to better target mast cells or their mediators for treatment of fibrotic disease. Citation: Strattan, E.; Hildebrandt, Keywords: mast cells; GVHD; fibrosis; transplant; autoimmune; pathogenesis G.C. -

Obesity: Teaching an Old Drug New Tricks—Amlexanox Targets

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Nature Reviews Endocrinology 9, 185 (2013); published online 26 February 2013; doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.42 © iStockphoto/Thinkstock OBESITY Teaching an old drug new tricks—amlexanox targets inflammation to improve metabolic dysfunction mlexanox, an anti-inflammatory were already obese: to leptin-deficient of obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus is medication used to treat mouth ob/ob mice, to test the drug’s effects on bound to generate a vast amount of interest. Aulcers and asthma, could have some genetic obesity, and to diet-induced “The specific action of amlexanox is benefit for the treatment of obesity and obese mice. Body weights of both groups remarkable,” comments Michael I. Goran type 2 diabetes mellitus, a study published returned to almost normal, and the weight (Keck School of Medicine, Childhood in Nature Medicine shows. Moreover, the loss was maintained for as long as the drug Obesity Research Center, University of findings shed light on how energy balance was administered. Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, is regulated by inflammation. To elucidate the mechanism underlying USA), who is not affiliated with the study. Myriad studies in animals and in the effects of amlexanox, the investigators “This very targeted approach to reduce humans implicate inflammation in the performed a detailed assessment of inflammation might cause less serious development of obesity-associated insulin metabolic parameters, including insulin adverse effects compared with blunting a resistance. “We have been studying sensitivity (by hyperinsulinaemic whole arm of the inflammation pathway,” inflammatory links between obesity and euglycaemic clamp studies), energy points out Goran, “and could potentially insulin resistance for some time, with expenditure (by indirect calorimetry), avoid a trade-off between improving a particular focus on macrophages in phosphorylation patterns and in vivo and metabolic health and the potential adverse adipose tissue,” recounts senior study in vitro changes in energy disposition. -

Pharmecovigilance and the Environmental Footprint of Pharmaceuticals Ilene S

PharmEcovigilance and the Environmental Footprint of Pharmaceuticals Ilene S. Ruhoy, MD, PhD Touro University Nevada Institute for Environmental Medicine Henderson, NV Christian G. Daughton, PhD U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development Las Vegas, NV US EPA Notice Although this work was reviewed by EPA and approved for publication, it may not necessarily reflect official Agency policy. PPCPs as Environmental Pollutants? PPCPs are a diverse group of chemicals comprising all human and veterinary drugs (available by prescription or over-the-counter, including “biologics”), diagnostic agents (e.g., X-ray contrast media), “nutraceuticals” (bioactive food supplements such as huperzine A), and other consumer chemicals, such as fragrances (e.g., musks) and sun-screen agents (e.g., 4-methylbenzylidene camphor; octocrylene); also included are “excipients” (so-called “inert” ingredients used in PPCP manufacturing and formulation; e.g., parabens). 1st National Survey Revealed Extent of PPCPs in Waterways • USGS “Reconnaissance” study in 1999-2000 was first nationwide investigation of pharmaceuticals, hormones, & other organic contaminants: – 139 streams analyzed in 30 states – 82 contaminants identified (many were pharmaceuticals) – 80% streams had 1 or more contaminant – Average 7 contaminants identified per stream • Since 1998, peer reviewed papers on PPCPs have increased from fewer than 200 per year to greater than 1,000 per year Kolpin DW,et al. "Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants