A Growing Concern: 2016 Child Care Fees in Canada's Big Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gtbank, Okomu, Access, Dangote Cement, Zenith, Top Analysts' Stock

MARKETS AND COMMODITIES MONITOR News COMMODITIES EXCHANGE RATE FMDQ Close FX outlook: When Oil US $56.91 NSE Close BDC TRAVELEX FX Treasury bills FGN Bonds) $-N400 356 $/N 3M 6M 5Y 10Y 20Y can we expect GOLD $ 1,178.60 39.30 £N598 N/A 0.00 0.08 0.67 0.02 0.10 0.05 uninterrupted supply COCOA $ 2,261.00 26,251.39 €N510 N/A 305.00 13.48 18.71 16.04 16.51 16.52 in the market? Page 8 FIFTEEN YEARS OF DEFENDING LIBERAL ECONOMIC THOUGHT NEWS YOU CAN TRUST I ** MONDAY 09 JANUARY 2017 I VOL. 14, NO 262 I GN300 Slashed import GTBank, Okomu, Access, Dangote Cement, tariffs will cut production cost Zenith, top analysts’ stock picks for 2017 – Manufacturers ODINAKA ANUDU & AMAKA ANAGOR-EWUZIE IHEANYI NWACHUKWU & INNOCENT UNAH ment Plc, and Zenith Bank Plc cent equity market return or available to BusinessDay, even anufacturers and trade are among some of analysts’ N603.68billion value loss in though in the first trading week experts predict that the espite a scaling- picks for year 2017. 2016, many stock buyers are into 2017, the share price of GT- MFederal Government’s back of expecta- Also found in the basket of eagerly searching for investment Bank lost N1.16 from year-open decision to slash import tariffs tions on a number most analysts’ stock picks are clues on some value stocks to level of N24.70 to close N23.54 on raw materials and machinery of listed compa- Flour Mills of Nigeria Plc, Nige- place their money on this year. -

Banking: Reading

Banking: Reading The concept of banking may have been a good one initially but I can’t help feeling that in today’s world there are less people benefiting. Of course it’s good to know that your money is safe and sound, but it does seem strange to pay an organization for having your money when they make a profit from this. The charges nowadays in some banks (and different banks in different countries vary enormously) are incredible. Some charge for an overdraft facility even if you don’t go overdrawn, some charge every time you take money out (your money!) while others charge for closing an account! If you’re not careful, it’s a way of losing money rather than keeping it safe. Perhaps because of this there are some interesting alternative money systems. In fact there are some banks that don’t use money at all. Time banks are an example of this. Instead of Pounds, Dollars, Euros etc., the currency is ‘time’ – issued in the form of time credits. As this is an egalitarian system, everyone’s time is valued equally so one time credit is equivalent of one hour’s work, whatever the work. The idea is that whenever you do something to help another person you are given a time credit for this rather than cash. So, for example, if you spend an hour looking after the kids next door you’ll be given one time credit. This you can then spend on an hour’s yoga class or having your front door painted. -

Doc ~ Alternative Currencies « Read

Alternative currencies \ PDF \\ MQLTCZJO8P Alternative currencies By - Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x7 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 47. Chapters: Community currencies, Private currencies, Local currency, Local Exchange Trading Systems, Ithaca Hours, Silvio Gesell, Freiwirtschaft, UIC franc, Freigeld, Liberty Dollar, Findhorn Ecovillage, Stelo, History of Chatham Islands numismatics, Emissions Reduction Currency System, Private currency, List of community currencies in the United States, Cornish currency, Community Exchange System, Complementary currency, BerkShares, RAAM, Digital currency exchanger, Time-based currency, Antarctican dollar, Potomac, Quasi Universal Intergalactic Denomination, Crédito, Chiemgauer, Disney dollar, Lewes Pound, WIR Bank, Neutral Unit of Construction, Terra, Kelantanese dinar, Totnes pound, Ecosimia, Eco-Pesa, PLENTY, Detroit Community Scrip, Hero Card, Toronto dollar, Stroud pound, Calgary Dollar, Fourth Corner Exchange, Fureai kippu, Occitan, Eco-Money, Multi registry system, Abeille, SOL Project, Acmetal, Saber, Urstromtaler, Nagorno-Karabakh dram, Instrodi, Flex dollar, Seborga luigino, Ora, Ural franc, Sectoral currency, Uned, Aspen dollar. Excerpt: The Liberty Dollar (ALD) was a private currency produced in the United States. The currency was embodied in minted metal rounds similar to coins, gold and silver certificates and electronic currency (eLD). ALD certificates are 'warehouse receipts' for real gold and silver owned by... READ ONLINE [ 8.26 MB ] Reviews This ebook can be worthy of a read, and much better than other. I have read and i am certain that i am going to planning to go through again once again in the future. You may like just how the writer compose this book. -

UNIVERISITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Petrodollar Era And

UNIVERISITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Petrodollar Era and Relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969-1980 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by David M. Wight Dissertation Committee: Professor Emily S. Rosenberg, chair Professor Mark LeVine Associate Professor Salim Yaqub 2014 © 2014 David M. Wight DEDICATION To Michelle ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Road to the Oil Shock 14 CHAPTER 2: Structuring Petrodollar Flows 78 CHAPTER 3: Visions of Petrodollar Promise and Peril 127 CHAPTER 4: The Triangle to the Nile 189 CHAPTER 5: The Carter Administration and the Petrodollar-Arms Complex 231 CONCLUSION 277 BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1.1 Sectors of the MENA as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 19 Figure 1.2 Selected Countries as Percentage of World GNI, 1970-1977 20 Figure 1.3 Current Account Balances of the Non-Communist World, 1970-1977 22 Figure 1.4 Value of US Exports to the MENA, 1946-1977 24 Figure 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 255 iv LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Net Change in Deployment of OPEC’s Capital Surplus, 1974-1976 120 Table 5.1 US Military Sales Agreements per Fiscal Year, 1970-1980 256 v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a cliché that one accumulates countless debts while writing a monograph, but in researching and writing this dissertation I have come to learn the depth of the truth of this statement. -

Fifth Grade Il Curriculum.Pdf

Our goal is simple: To make implementation of the Financial Literacy and Inquiry Standards easy for all Illinois teachers. Using the C3 Framework as a guide, our curriculum provides teachers all the resources they need for each unit while ensuring the standards are taught. Below is a brief explanation of the structure our units take. Inquiry To break down the inquiry process, each lesson follows this format: Ask Investigate Create/Discuss Reflect Ask Each lesson starts with a compelling question. Next, there are three supporting questions that directly ties in to the compelling question. Each supporting question gets a little tougher as you progress through the lesson, thus providing the opportunity for differentiating and compacting the curriculum. Investigate The featured resources are listed here. Depending on the lesson, these can range from reading for information pieces to videos to activities. These resources were designed to allow the students to do their own research and learn about the compelling question. Each resource has been created for you. If a lesson lists a video as a resource, you can find it at www.moneymindedillinois.com. Create/Discuss Here you will find the formative assessment performance activities for each supporting question. As in Investigate, the activities have all been created and are in the unit. Reflect This section is the lesson’s summative assessment performance activity. Additional Resources Our curriculum will continuously have additions and adaptations. Please feel free to visit us at www.moneymindedillinois.com for more materials as the program grows. There are also statewide competitions that students can partake in listed there as well. -

The Social Justice Community in Toronto

The Social Justice Community in Toronto A Report for the George Cedric Metcalf Charitable Foundation Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 3 Part I: Challenges for Urban Social Justice Movements: Neoliberal Urbanism, the Canadian City and Toronto.............. 4 Part II: The Social Justice Community in Toronto...........................16 Appendix 1: The Centre for Social Justice Mission Statement ......23 Appendix 2: Outreach Survey Letter to Toronto Social Justice Organizations .....................................25 Appendix 3: CSJ News Letter Sample ...........................................28 Appendix 4: Groups Struggling Against Poverty and Inequality in Ontario .........................................................39 Appendix 5: Get Social Campaign .................................................46 Appendix 6: Factsheets on Poverty................................................48 Appendix 7: Toronto Social Justice Groups Data Base .................72 3 The Social Justice Community in Toronto A Report for the George Cedric Metcalf Charitable Foundation Centre for Social Justice INTRODUCTION This report has two main parts. The first is an analytical discussion paper prepared at the conclusion of the work to assess our understanding of urban politics today, the challenges for urban social justice movements and community organizations, and the specific contexts for some of these issues in Toronto. It is part of our final evaluation allowing us to focus our research and educational efforts, after a lengthy period of restructuring, and how we might develop CSJ work in the future. The second part reports on the specific work for the grant. It includes a report on the specific tasks that were set to aid social justice community building, the fact sheets developed and two inventories on social justice work in Toronto. It also provides a review of the work that the CSJ has done that has overlapped with the terms of reference set out in the work with the Metcalfe Foundation. -

Joy Kogawa Fonds . - 1940-1992

Joy Kogawa An inventory to the fonds in the University of British Columbia Library Special Collections Prepared by Sayuri Tsuruta September 199 6 c:\wp51 \kogawa Joy Kogawa fonds . - 1940-1992. 9 .3m of textual records . 35 posters. 58 photographs . Joy Nozomi Kogawa (nee Nakayama) was born in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1935 to Japanese Canadian parents, Gordon Goichi Nakayama and Lois Masui Nakayama . Gordon G . Nakayama was a Japanese Anglican clergyman (the Nakayama-sensei in Joy' s novel Obasan) and had a significant role in the Japanese Canadian community before , during and after World War II . Lois was a kindergarten teacher and singer, and Joy' s brother Timothy is a clergyman, who worked in Alberta and Seattle, Washington, and is no w working in Okinawa, Japan. Joy and her family were evacuated from Vancouver along with thousands of other Japanese Canadians and moved to Slocan City, in interior British Columbia in 1942, where she had the primary education. The family then moved to Coaldale, Alberta in 1945 . She received a temporary license to teach from the Calgary branch of the University of Alberta in 1954 after attending a one year temporary license course in education, and taugh t elementary school in Coaldale. She studied theology at the University of Toronto and musi c at Royal Conservatory in Toronto in 1956 . She then moved back to Vancouver in 1957 , where she taught elementary school for one year . She attended the University of Saskatchewan in 1967 taking courses in English, philosophy and psychology. From December 1973 through 1975, she worked for Pierre Trudeau in the Correspondenc e Division of the Prime Minister's Office . -

HACKING the UTURE of MONEY BRETT SCOTT • the Heretic's Guide to Global Finance the Heretic's Guide to Global Finance

A unique inside-out look at our financial system HACKING THE UTURE OF MONEY BRETT SCOTT • The Heretic's Guide to Global Finance The Heretic's Guide to Global Finance Hacking the Future of Money Brett Scott First published 2013 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin's Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Brett Scott 2013 The right of Brett Scott to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3351 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3350 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 8496 4879 0 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 8496 4881 3 Kindle eBook ISBN 9781 8496 4880 6 EPUB eBook Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America Contents Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Part 1: Exploring 1 Putting on Financial Goggles 15 2 Getting Technical 42 Part 2: jamming 3 Financial Culture-Hacking 91 4 Economic Circuitbending 128 Part 3: Building 5 Building Trojan Horses 177 6 DIY Finance 211 Conclusion 243 Further Resources 248 Index 250 For Horatio, Teo and Djembe Thanks for all the food and love Acknowledgements Thanks to mum, dad, and my brother Craig for everything. -

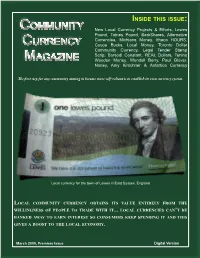

Local Community Currency Obtains Its Value Entirely From

INS I DE TH I S I SSUE : COMMUNITY New Local Currency Projects & Efforts, Lewes Pound, Totnes Pound, BerkShares, Alternative Currencies, Michiana Money, Ithaca HOURS, CURREN C Y Cocoa Bucks, Local Money, Toronto Dollar Community Currency, Legal Tender Stamp Scrip, Borsodi Constant, REAL Dollars, Tenino MAGAZINE Wooden Money, Wendell Berry, Paul Glover, Noney, Amy Kirschner & Antartica Currency The first step for any community aiming to become more self-reliant is to establish its own currency system. Local currency for the town of Lewes in East Sussex, England LOCA L COMMUNITY CURRENCY OBTAINS ITS VA L UE ENTIRE L Y FROM THE WI ll INGNESS OF PEOP L E TO TRADE WITH IT ... L OCA L CURRENCIES CAN ’T BE BANKED AWAY TO EARN INTEREST SO CONSUMERS KEEP SPENDING IT AND THIS GIVES A BOOST TO THE L OCA L ECONOMY . March 2009, Premiere Issue Digital Version http://www.flickr.com/photos/writemboyo/2960993841/ New Local Currency Projects & Efforts REAL Dollars - Local Currency for Page 4 Lawrence, Kansas (2000-2003) Lewes Pound Page 26 Page 6 The Complete Story of Tenino Wooden Totnes Pound Project Money Page 8 By Don Major Thurston County Independent, 2/19/65 BerkShares Success Enables Page 27 Exchange Rate Change Announcement from Berkshares The Idea of a Local Economy Page 9 by Wendell Berry Page 28 Fundamentals of Alternative Currencies and Value Measurement Noney by Thomas Greco Rhymes with money Page 10 Page 30 Michiana Money Is The New Sense Beyond The Dollar - A Primer Community Currency On Local Currencies Page 12 by Amy Kirschner Page 31 Ithaca HOURS use steady By David Durrett The Coldest Currency on The Planet? Page 13 BankOfAntartica.com Page 34 The Destiny of Dollars Cover by Paul Glover The Lewes one pound note features Page 14 Thomas Paine who lived in Lewes from 1768 - 1774. -

Download This PDF File

Follow the Money BY MARY-BETH RADDON Pour rbpondre ri 1 'incertitude financihe et ri la rarete' des Tooke).' The most prominent North devises depuis le milieu des anne'es 80, plus d'un millier de American models of community projets& monnaiecommun~utaireont uu lejourenAmbrique, currency are HOURS, a paper cur- en Europe, en Australie et en Nouvelle-Ze'lande. Cet article rency, and LETS (Local Employment The inherent examine les rnod2les nord-amhicains qui sont les plus andTradingSystem),anextended risks of financial importants: HOURS, une monnaie depapier, et LETS un re'seau "barter" network that uses crises are de troc qui utilise comme cridits des adollars-verts a. L 'auteure "greendollar" redi its.^ In commu- . assure que quoique les efforts collect$ pour britir une n& money networks all manner of down loaded communaute' autonome soient une re'ponse ade'quate ri un locally produced goods and services f rOm the board syt2me pricaire d'un financement mondial, ces initiatives are exchanged, from accountingserv- demandent un investissementsocialetuneattention concertbe ices to zipper repair. Community room, dealing afin que le de'se'quilibrequi menace lesfemmes auxprises avec exchange provides a supplementary room and les impacts ne'gattji du financement et les fluctuations de source of credit and employment, as counting room march6 mondial, ne soientpas les seules & en porter l bdieux. well as an avenue for creating per- son4 ties of support beyond the to the kitchen. "Follow the money" is the best advice for understanding immediate circl; of household and the scope and impact of economic globalization. Not- familial relationships. withstanding the expansion of global trade, the financial Although men are prominent in economy now hugely outstrips the material economy. -

Complementary Currency B

MEMORANDUM City of Delta Parks, Recreation & Culture Department To: Parks, Recreation & Culture Commission From: Ken Kuntz, Director of Parks, Recreation & Culture Date: April 27, 2018 Subject: Community Care for Seniors File No.: 14060-20 This memorandum is before the Parks, Recreation & Culture Commission (Commission) for information and discussion. At the direction of the Commission Chair, staff researched unique programs available to seniors at a local or regional level. This memo contains some of the findings and programs that are available in Japan and in Ontario. Over the past several years, articles and studies have been published on ways to empower and care for the elderly in Japan. Japan has the oldest population in the world. People over the age of 65 make up a quarter of Japan's population, and over the next several years will reach 40%. The top-heavy demographic creates huge challenges for local government and the overall economy on how to respond to caregiving challenges. Japan's government, businesses and society as a whole are facing challenges earlier than other countries, allowing the world to learn and benefit from their stumbles, innovations and experiments. Focusing on how to ensure an older population remains relevant in today's society and to stay ahead of the curve, Japan is tackling the issue with innovative programs including everything from comprehensive long-term care insurance introduced in 2000, to robotics. Historically adult children in Japan cared for their aging parents, now many are moving away. Not only are the adult children moving away, they are having less children due to an uncertain economic future. -

Curriculum Vitae

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036-2188 Tel: 202-797-6000 Fax: 202-797-6004 www.brookings.edu SPRING 2007 RALPH C. BRYANT Economic Studies Program The Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 202-797-6147 [email protected] Education 1966 Ph.D., Economics, Yale University 1963 B.Phil, Economics, Rhodes Scholar, Magdalen College, Oxford Univ. 1960 B.A., Economics, Magna cum Laude, Yale University Professional Background 1976-present Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Program. Edward M. Berrnstein Scholar. The Brookings Institution. 1972-1975 Director, Division of International Finance and Associate Economist for Federal Open Market Committee 1970-1972 Associate Advisor and Chief, Special Studies Section, Division of International Finance, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 1969-1970 Leave of Absence from Federal Reserve; Fellowship at University College, London and Bank of England 1967-1969 Assistant to the Director, Division of International Finance, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 1965-1967 Economist, Division of International Finance, Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve System 2 Professional Honors Chair, Board of Trustees, 1995-1997, Sidwell Friends School, Washington, D.C. Member, Board of Trustees, 1989-1997. 1995 Professional Fellow in Monetary Economics, Reserve Bank of New Zealand And Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Appointed by Queen Elizabeth as an Honorary Office of the Order of the British Empire 1989-1990