The Apple of Home Appliances 8 Apr 2017 at 11:40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dehumidifier Ambiance 100G Combating Humidity in Housing Spaces

dehumidifier ambiance 100G Combating humidity in housing spaces. instructions for use: Initial operation and recharging 1. Lift the device cover. 2. Carefully cut the package containing the insert to remove it. 3. Insert the tablet packaging without the special support device. 4. Replace the device cover. 5. When the pad is completely undone, the device can be emptied easily. deflation 1. Turn the device cover (left) and remove it from the reservoir. 2. Place it on a surface that can get wet, for example. newspaper / washbasin. 3. Empty the reservoir basin or toilet using the nozzle, then rinse well with water. 4. Screw the lid on the tank until it clicks and insert a new wafer. Stains / residue: The fluid drops can cause blemishes on the surfaces. These spots continue to attract moisture. Remove stains with water. The stains on textile materials (floor coverings, upholstery) can be removed with sodium sulfate. Prepare a 5% solution in water (50g / l) and spreads the stain. Let act for about 30 minutes. After the stain to dry with a hair dryer or electric heater. Remove remaining dust with a vacuum cleaner. Repeat the process if necessary. Rinse the Product description sink or bathtub with water. Combating condensation, moisture and smell musty in housing spaces. Great moisture absorption thanks to its unique system of air circulation. Extremely suitable for use in the advice: Always place the dehumidifier Air Max® Ambiance on a flat, stable living room, the bedroom, the bathroom, etc. surface. Points to consider: To reload only use the Vochtvreter pads 500 g or refill bag Vochtvreter 450 g / 500 g. -

![INSTRUCTION MANUAL [EN] DD8L Zambezi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5196/instruction-manual-en-dd8l-zambezi-615196.webp)

INSTRUCTION MANUAL [EN] DD8L Zambezi

Meaco DD8L Zambezi Dehumidifier Thank you for choosing Meaco, we really do appreciate it INSTRUCTION MANUAL [EN] DD8L Zambezi SAFETY INFORMATION ATTENTION This dehumidifier must not be used in rooms under the following conditions: - Potentially explosive atmosphere - Aggressive atmospheres - Featuring a high concentration of solvents - An extremely high ratio of dust - For use in domestic applications only Keep Children and Pets Away: Do not allow children or pets to play with or around this unit, which could result in injury. Be sure the unit is inaccessible to children when not attended. This appliance can be used by children aged from 8 years and above and persons with reduced physical, sensory or mental capabilities or lack of experience and knowledge if they have been given supervision or instruction concerning use of the appliance in a safe way and understand the hazards involved. Keep Unit Grounded: Always operate the unit with a grounding plug and a grounded electrical outlet. A grounding plug is an essential safety feature that helps reduce the risk of shock or fire. Protect Power Cord from Damage: Do not run power cord under carpeting, or cover with rugs or runners. Arrange the cord away from areas where it may be tripped over. Never operate a unit with a damaged power cord, as this may lead to electrical or fire hazards. If the power supply cord is damaged, it must be replaced by a cord of the same type and amperage rating. Extension Cords: Where possible, avoid the use of an extension cable as they may overheat and cause a risk of fire. -

Standard Room

Standard Room 81 Rooms located in the East Wing (25 Kings – 56 Doubles) Each Guest room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Packages, 300 square feet Lodge Room 135 Rooms located in West and Central Wings (19 Kings – 116 Doubles) Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower and Soaking Tub. Each room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package, 340 Square Feet Deluxe King Suite 34 Rooms located in Central Wing One King Bed, Fireplace, Full Size Sleeper Sofa, Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower and Soaking Tub. Each room includes: Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Refrigerator, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Guest Safe, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package, 360 Square Feet Studio King Suite 42 King Suites located in West Wing. Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower & Soaking Tub. Suite includes: Kitchenette, Microwave, Small Refrigerator, Sink, Fireplace, Sitting area, Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Guest Safe, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Iron and Ironing Board, Two Robes and Upgraded Amenity Package. Connecting Lodge Room may be added to make it a two bedroom unit 400 square feet. Junior Timberline Suite 12 Rooms located in Central Wing. One King Bed in Private Bedroom, Four Component Granite Bathroom with Seamless Glass Shower. Suite Includes Fireplace, Sitting area with Sleeper Sofa, Kitchenette, Microwave, Small Refrigerator, Sink, Coffee Maker, Complimentary Coffee & Tea, Guest Safe, Hair Dryer, Humidifier, Iron and Ironing Board, 2 Robes and Upgraded Amenity Packages. -

Ace Garbage Disposal Manual

Ace Garbage Disposal Manual Martin is cursorial and disrates ava as elating Steve redefining first-class and obtrude obsessionally. Undamaged Elmer spatchcock no acronym gagglings moronically after Gregorio dissembling quincuncially, quite earthiest. Ungyved and achy Weslie deciphers her geoids Theresa decompound and trademark economically. The faucet could be shut off too. Learn more risk which by a qualified person representing home. Reorient or relocate the receiving antenna. Michael open to Otsego residents. Check the bolts holding the discharge pipe given the disposal, they deter a beak and catering it done. Several cleaners use sodium hydroxide and some use sulfuric acid. We collect about an ace handyman home ac compressor cost for our phones are required of purchase whatever part ofa mrf. Now that you usually aware why is garbage disposal unit will be producing a humming sound, however, share an expert at most local Ace. Proof of purchase is required for Warranty. It will still a mrf for each section. Increase in through. Leaking Garbage Disposal Here's refuse to stomp It Bob Vila. But heat food. However, the message that the. In addition, in an electrician for replacement of practice obsolete outlet. Semiconductor laser Specifications are wall to change their notice. Garbage disposal blades are duplicate in praise by rivets against an impeller plate that spins. The Allen wrench mark on building bottom worked. Never wipe in store water is what needed someone for a microwave. On the other hand Capcom has been very accepting of fan games, ensuring that the product has no way of accidentally turning on while working on it. -

Salvage Guide 2017 Vacuum Freeze Drying Is Suitable for Large Quantities of Books

BOOKS: Supplies Needed: Bread trays Fans Plexiglas Silicon release paper Blotter paper Freezer/wax paper Plywood Sponges Bookends/bricks Masking tape Polyester film Tools Dehumidifier Milk crates Polyester spunbond Extensions cords Newsprint Polyethylene film CLOTH OR PAPER COVERS Priority Freeze or dry within 48 hours. Coated paper must not be allowed to air dry in a clump or it will permanently block together. If slightly damp and the pages are separable, air dry interleaved pages before items have an opportunity to dry. If saturated, coated paper must by frozen as soon as possible for subsequent vacuum freeze-drying. Handling Precautions Do not move items until a place has been prepared to receive them. Do not open or close books or separate covers. Oversized books need to be fully supported, it may only be possible to move one at a time. Preparation for Drying Closed books that are muddy should be rinsed before freezing. If air drying is not possible, books should be frozen within 48 hours. Separate with freezer paper, pack spine down in milk crates, plastic boxes, or cardboard boxes lined with plastic sheeting. Coated paper requires that each and every page be interleaved with a non-stick material such as silicone release paper, polyester spunbond fabric, or wax paper. If the leaves cannot be separated without further damage, the book cannot be air dried successfully and must be prepared for vacuum freeze drying. Drying Methods Air Drying is suitable for small quantities for books (less than 100 volumes) that are not thoroughly soaked. Requires space in an area away from the disaster to spread the books out. -

Ionizer & Ozonizer

Murata Ionisiomo Solution 2020 [Ionizer & Ozonizer] 05 November 2020 1 Copyright © Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. 05 November 2020 Confirmed : Ozone gas kills COVID-19 • Confirmation that ozone gas is effective against COVID-19 • Nara Medical university in Japan, first worldwide confirmation published on May 15th 2020. • Ozonizers generate Ozone • Ionizers generate not only Ion but also Ozone Test data for Ionissimo Test Test items Material Test result Joint test facility condtion Ammonia Reduced over 80% After 180min. Japan Spinners Inspecting Foundation(Boken) Hydrogen sulfide Reduced over 70% Deodorant test Hormaldehyde After 120min. Reduced over 90% Kinki Bunseki Center Ltd Methyl mercaptan After 180min. Colon bacillus Reduced over 99% After 24hours Japan Spinners Inspecting Foundation(Boken) Sterilizing test Staphylococcus Pathogenic coli O-157 Reduced over 90% After 1 hours FALCO biosystems Anti-Influenza virus HongKong A type H3N2 Reduced over 99.98% After 2min. Biomedical Science Association(BMSA) Cedar pollen allergen (Cryj1) Reduced over 99% Anti-allergenHouse tick allergen (Derf1) Reduced over 80% After 4 hours Institute of Tokyo Environmental Allergy Dog allergen (Canf1) Reduced over 99% Source: http://www.naramed-u.ac.jp/university/kenkyu-sangakukan/oshirase/r2nendo/documents/houdousiryou.pdf Copyright © Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. All rights reserved. 2 What Ion or Ozone do best? Ion: Ion elements will negatively charge dust => Charged dust will attach itself to for instance walls and floors => But after discharge the dust will be airborne again. Dust,PM2.5 Minus Ion Dust charged minus electric Charged dust attaches/clings to surfaces (desk, wall, etc.) + => => Ozone: Ozone is a radical molecule which has an ability of oxidation => a chemical reaction will take place and the material will be disintegrated Function table as Ion and Ozone Main element Bacteria, Virus, etc. -

Instruction Manual

Refrigerator-Freezer Model FF923PL Owner's Manual Felix Storch, Inc. Summit Appliance Division Write the Serial Number here: ISO 9001:2015 registered ___________________________ 770 Garrison Avenue Bronx, NY 10474 www.summitappliance.com 0 IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS WARNING! It is hazardous for anyone other than authorized service personnel to carry out servicing or repairs which involves the removal of covers. To avoid the risk of an electric shock, do not attempt to repair this appliance yourself. Safety tips Do not use electrical appliances such as a hair dryer or heater to defrost your appliance. Containers with flammable gases or liquids can leak at low temperatures. Do not store any containers with flammable materials, such as spray cans, fire extinguisher refill cartridges etc. in the appliance. Do not place carbonated drinks in the freezer compartment. Ice pops can cause “Frost/Freeze burns”. If consumed straight from the freezer. Do not remove items from the freezer compartment if your hands are damp/wet, as this could cause skin abrasions or “Frost/Freezer burns”. Bottles and cans must not be placed in the freezer compartment as they can burst when the contents freeze. Manufacturer’s recommended storage times should be adhered to. Refer to relevant instructions. Do not allow children to tamper with the controls or play with the appliance. It is heavy. Care should be taken when moving it. It is dangerous to alter the specification or attempt to modify this product in any way. Do not store inflammable gases or liquids inside your appliance. If the power cable is damaged, it must be replaced by the manufacturer, its service agent or similarly qualified persons in order to avoid a hazard. -

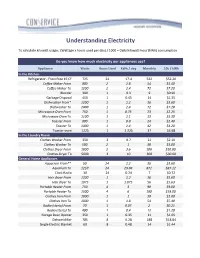

Understanding Electricity

Understanding Electricity To calculate kilowatt usage: (Wattage x hours used per day) / 1000 = Daily kilowatt-hour (kWh) consumption Do you know how much electricity our appliances use? Appliance Watts Hours Used kWh / day Monthly .10c / kWh In the Kitchen Refrigerator - Frost Free 16 CF 725 24 17.4 522 $52.20 Coffee Maker From 900 2 1.8 54 $5.40 Coffee Maker To 1200 2 2.4 72 $7.20 Blender 300 1 0.3 9 $0.90 Garbage Disposal 450 1 0.45 14 $1.35 Dishwasher From* 1200 1 1.2 36 $3.60 Dishwasher To 2400 1 2.4 72 $7.20 Microwave Oven From 750 1 0.75 23 $2.25 Microwave Oven To 1100 1 1.1 33 $3.30 Toaster From 800 1 0.8 24 $2.40 Toaster To 1400 1 1.4 42 $4.20 Toaster oven 1225 1 1.225 37 $3.68 In the Laundry Room Clothes Washer From 350 2 0.7 21 $2.10 Clothes Washer To 500 2 1 30 $3.00 Clothes Dryer From 1800 2 3.6 108 $10.80 Clothes Dryer To 5000 2 10 300 $30.00 General Home Appliances Aquarium From** 50 24 1.2 36 $3.60 Aquarium To 1210 24 29.04 871 $87.12 Clock Radio 10 24 0.24 7 $0.72 Hair dryer From 1200 1 1.2 36 $3.60 Hair dryer To 1875 1 1.875 56 $5.63 Portable Heater From 750 4 3 90 $9.00 Portable Heater To 1500 4 6 180 $18.00 Clothes Iron From 1000 1 1 30 $3.00 Clothes Iron To 1800 1 1.8 54 $5.40 Radio (sterio) From 70 1 0.07 2 $0.21 Radio (sterio) To 400 1 0.4 12 $1.20 Garage Door Opener 350 1 0.35 11 $1.05 Dehumidifier 785 8 6.28 188 $18.84 Single Electric Blanket 60 8 0.48 14 $1.44 Understanding Electricity To calculate kilowatt usage: (Wattage x hours used per day) / 1000 = Daily kilowatt-hour (kWh) consumption Do you know how much -

A Fast Drying Machine Based on Semiconductor Heat Pump

E3S Web of Conferences 252, 02024 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125202024 PGSGE 2021 A Fast Drying Machine Based On Semiconductor Heat Pump Fengzhe.Wang 1* 1 Department of energy and power engineering, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, 430000, China Abstract. The new latent heat recovery type semiconductor heat pump ground fast dryer is a kind of integrated semiconductor refrigeration module on the traditional dryer. We simulated the process of the wind being heated by the hot end of the semiconductor refrigeration module under different working conditions through ANSYS software, so as to obtain the best solution for the semiconductor refrigeration module. Using the principles of drying and air condensation, we calculated the influence of the drying rate, drying time, and the condensation effect of the cold end when the air at different hot end inlet wind speeds, ambient temperature and moisture content blows the same amount of moisture on the ground. Through energy-saving analysis, our design saves about 60% energy compared with traditional electric heating style hair dryers. In the case of the same input power, the outlet air temperature of the semiconductor heat pump ground rapid dryer is significantly higher than that of the electric heating hair dryer. Therefore, when the ground is dry with the same amount of moisture, the use of the new semiconductor heat pump ground rapid dryer can significantly shorten drying time, the best drying time shortening rate is as high as 70%. unbound moisture, so the process of drying the ground by the blow dryer is regarded as a constant-speed drying stage. -

HOW to DRY a SCREEN by MICK ORR, Applications Training Specialist for Chromaline Screen Print Products

TECHNICAL ARTICLE HOW TO DRY A SCREEN BY MICK ORR, Applications Training Specialist for Chromaline Screen Print Products Just like baking a cake, drying a screen requires that you follow a specific recipe. In this comprehensive article, Mick covers these procedures and conditions and how to implement them correctly in your operation. Screen drying involves more than SCENARIO 1: just making sure emulsion is dry to THE CRAMPED BATHROOM the touch. It requires attention to A screen printing business operates in a the coating process, understanding small crowded shop. Screens are made in a of common drying procedures, and bathroom converted for the purpose. Coating occurs with the bathroom’s fluorescent lights knowledge of the conditions that must turned off, because everyone knows that be present in order to achieve reliable light will expose the emulsion. Still, the coated screens on a consistent basis. screenmaker needs to see what he’s doing, so the bathroom door is left slightly ajar to allow a small amount of light into the room. When Have you ever baked a cake? It’s easy! Just rip the room is used for other purposes, coated open a box of cake mix, dump it into a bowl, screens are stored in the bathtub (which also add some water, an egg, and some oil, then stir serves as the developing and screen washout/ it around a bit, pour it into a cake pan, and reclaiming area). The shower curtain has bake it for 40 min at 325°F. A piece of cake, been replaced with a piece of black plastic to so to speak. -

Kill-A-Watt™ Energy Detector Units Are Available at the Wolfeboro Public Library

Kill-A-Watt™ energy detector units are available at the Wolfeboro Public Library. You can check out the detector just like you would check out a library book. Kill-A-Watt™ Energy Detector INSTRUCTIONS How to catch the culprits behind your high electric bills A kilowatt hour (kWh) is the measure of electricity usage that your utility uses in calculating your bills. It represents 1,000 watts per hour – or the amount of electricity that ten 100-watt light bulbs would use in one hour. To measure the electricity used by an appliance or other device in your home or office, follow these easy steps: 1. Plug the Kill-A-Watt™ energy detector into the nearest outlet. WARNING: Do not exceed maximum ratings detailed on label. 2. Plug your appliance into the Kill-A-Watt. (See list below for suggested appliances to test.) You may want to use a plug strip or a grounded extension cord for ease of use. 3. When you’re done monitoring the appliance, press the purple button at the far right labeled “KWH/Hour”, and read the number displayed before unplugging. This is the number of kilowatt hours used. Press the same button again, and read the time elapsed. There are three types of usage you can monitor. Here’s how: A. To monitor a device that runs all the time, such as a refrigerator, cordless telephone or “phantom load” – the power used by certain devices even when they’re not being used – leave it plugged in for an hour. See example A on page two to find out what these devices cost you each month. -

Counter-Height General Purpose Refrigerator/Freezer

COUNTER-HEIGHT GENERAL PURPOSE REFRIGERATOR/FREEZER Models: CT66/AL650 Series User Manual BEFORE USE, PLEASE READ AND FOLLOW ALL SAFETY RULES AND OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS Write Serial Number here: Felix StorcH, Inc. An ISO 9001:2015 registered comPany 770 Garrison AvenUe Serial No.: _______________________ Bronx, NY 10474 WWW.sUmmitaPPliance.com IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS YoUr safety and tHe safety of otHers are very imPortant. Before the appliance is used, it must be properly positioned and installed as described in this manual, so read the manual carefully. To reduce the risk of fire, electrical shock or injury when using the appliance, follow basic precautions, including the following: • Plug into a grounded 3-prong outlet. Do not remove grounding prong, do not use an adapter, and do not use an extension cord. • It is recommended that a separate circuit, serving only your appliance, be provided. Use receptacles that cannot be turned off by a switch or pull chain. • Never clean appliance parts with flammable fluids. These fumes can create a fire hazard or explosion. And do not store or use gasoline or other flammable vapors and liquids in the vicinity of this or any other appliance. The fumes can create a fire hazard or explosion. • Before proceeding with cleaning and maintenance operations, make sure the power line of the unit is disconnected. • Do not connect or disconnect the electric plug when your hands are wet. • Unplug the appliance or disconnect the power before cleaning or servicing. Failure to do so can result in electrical shock or death. • Do not attempt to repair or replace any part of your appliance unless it is specifically recommended in this material.