Download This Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Festival 2009 Timetable

Download Festival 2009 Timetable Friday Saturday Sunday Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull Main 2nd Tuborg Red Bull 11:00 11:00 11:00 11:05 11:05 Auger 11:05 Stone Sacred Mother Fall From 11:10 11:10 Ripper Acid Drop 11:10 Brides 11:15 11:15 The Crave Bane 11:15 Gods Tounge Grace 11:20 11:20 Owens 11:20 11:25 11:25 11:25 11:30 11:30 11:30 11:35 11:35 11:35 11:40 11:40 11:40 11:45 11:45 11:45 Trigger 11:50 11:50 No 11:50 Violent 11:55 11:55 Five Symphony Japanese 11:55 Tesla The Raucous 12:00 12:00 Americana 12:00 Soho 12:05 12:05 Finger Voyeurs 12:05 Bloodshed Jays 12:10 12:10 Cult 12:10 12:15 12:15 Death 12:15 12:20 12:20 12:20 12:25 12:25 Punch 12:25 12:30 12:30 12:30 12:35 12:35 12:35 Suicide 12:40 12:40 Black 12:40 Turbowolf 12:45 12:45 The 12:45 Million Dollar 12:50 12:50 Hardcore 12:50 Skin Silence 12:55 12:55 Spiders Computers 12:55 Reload 13:00 13:00 Superstar 13:00 13:05 The 13:05 Devil 13:05 Hollywood Sleepercurve 13:10 Steadlür Instigators 13:10 13:10 13:15 Undead 13:15 Driver 13:15 13:20 13:20 13:20 Pulled Apart 13:25 13:25 13:25 God 13:30 13:30 13:30 Black By Horses 13:35 13:35 Facecage 13:35 Forbid 13:40 Hunting The 13:40 In Case 13:40 13:45 13:45 Serpico 13:45 Stone Jettblack 13:50 In This Minotaur 13:50 Of Fire 13:50 Cherry 13:55 The Tripswitch 13:55 13:55 14:00 Moment 14:00 14:00 14:05 14:05 14:05 14:10 Blackout 14:10 14:10 Esoterica 14:15 14:15 Hatebreed 14:15 14:20 14:20 14:20 Sevendust 14:25 Bleed From 14:25 Loverman 14:25 14:30 A Day 14:30 14:30 14:35 Within 14:35 Forever 14:35 Fei 14:40 To Young 14:40 -

I Trade DVD-DL on a 3:1 Base, Blu-Rays Only for Blu

I trade DVD-DL on a 3:1 Base, Blu-Rays only for Blu-Rays and RT (rare shows) only for other RTs in return, if you see a RT show on other lists as common, trade it with this guy and not with me Grey = Authored by me Red = Filmed by me Blue = Blu-Ray (BD) I DON’T SELL ANY BOOTLEGS , I'M JUST MAKING TRADES!!! __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 12.05.1981 Palais de Beaulieu - Lausanne, Switzerland 26.09.1981 Rockfestival - Solothurn, Switzerland (Crownkocher;Thumraider) xx.12.1982 Solingen, Germany 01.03.1985 Johanneshovs Isstadion - Stockholm, Sweden 27.04.1986 Forest National - Brussels, Belgium 27.06.1986 IMA Sports Arena - Flint, MI, USA (Damage Inc.) 23.06.1989 Fat Jak's Night Club - Council Bluffs, IA, USA 30.04.1993 Halle Gartlage - Osnabrück, Germany 03.05.1993 Mejeriet - Lund, Sweden (Havrefras) 18.05.1993 Zimba - Milan, Italy 15.10.1993 L'Amours - Brooklyn, NY, USA 23.10.1993 The Ritz - Roseville, MI, USA 26.11.1994 Tavastia Club - Helsinki, Finland 02.05.1996 Pumpenhurst - Copenhagen, Denmark 31.05.1996 Buenos Aires, Argentina (PRO) 27.04.2005 Luzhniki Sports Arena - Moscow, Russia 08.07.2005 Rockwave Festival - Terravibe, Greece (Left Angle;Incl. Slayer) 11.08.2005 Sziget Festival - Budapest, Hungary 26.06.2010 Besiktas Inönü Stadium(Sonisphere) - Istanbul, Turkey (Efooo;Nikky Syxx) 27.09.2010 B.B. King Blues Club & Grill - New York, NY, USA (YT shit) 04.02.2011 Klub Studio - Krakau, Poland (1DVD-DL)( Damian Kaplita) 10.02.2011 Live Music Hall – Cologne, -

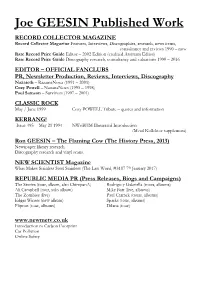

Joe GEESIN Published Work

Joe GEESIN Published Work RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Record Collector Magazine Features, Interviews, Discographies, research, news items, consultancy and reviews 1990 – now Rare Record Price Guide Editor – 2002 Edition (credited Assistant Editor) Rare Record Price Guide Discography research, consultancy and valuations 1990 – 2016 EDITOR – OFFICIAL FANCLUBS PR, Newsletter Production, Reviews, Interviews, Discography Nazareth – RazamaNewz (1991 – 2001) Cozy Powell – NananaNews (1995 – 1998) Paul Samson – Survivors (1997 – 2001) CLASSIC ROCK May / June 1999 Cozy POWELL Tribute – quotes and information KERRANG! -Issue 495 May 21 1994 NWoBHM Illustrated Introduction (Metal Kollektor supplement) Ron GEESIN – The Flaming Cow (The History Press, 2013) Newspaper library research. Discography research and vinyl scans. NEW SCIENTIST Magazine What Makes Stainless Steel Stainless (The Last Word, #3107 7th January 2017) REPUBLIC MEDIA PR (Press Releases, Biogs and Campaigns) The Stories (tour, album, also ChimpanA) Rodrigo y Gabriella (tours, albums) Ali Campbell (tour, solo album) Mike Batt (live, albums) The Zombies (live) Paul Carrack (tours, albums) Edgar Winter (new album) Sparks (tour, albums) Flipron (tour, albums) Dilana (tour) www.newmetv.co.uk Introduction to Carbon Footprint Car Pollution Online Safety RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE – Feature Articles Issue 165 May 1993 GILLAN – Feature, Ian Gillan Interview, Gillan Band Discography, vinyl scans Issue 179 July 1994 NAZARETH – Feature, Dan McCafferty Interview, Darrell Sweet Interview, Discography, -

David Coverdale Talks About the New Whitesnake Album

GRTR! Playlists April 2008 – June 2008 April 2008 Date: SUNDAY APRIL 6 2008 TIME: 15:00 – 17:00 116:51 ARTIST TITLE ALBUM/YEAR TIME 1. DOKKEN Standing On The Outside Lightning Strikes Again (2008) 3:54 2. WHITESNAKE Can You Hear The Wind Blow Good To Be Bad (2008) 5:02 3. EUROPE Always The Pretenders Single (2006) 3:30 4. KING’S X Move XV (2008) 4:02 5. STEVE WINWOOD Dirty City Single (2008) 4:02 6. GARY MOORE Empty Rooms The Platinum Collection (2006) 4:18 7. JOE SATRIANI Overdriver Professor Satchafunkilus and 5:10 the Musterion of Rock (2008) 8. JOE SATRIANI The Extremist The Extremist (1993) 3:45 9. NICKLEBACK Fight For All The Wrong All The Right Reasons (2005) 3:46 Reasons 10. ALICE COOPER Feed My Frankenstein Classicks (1995) 4:44 11. BLACK TIDE Shockwave Single (2008) 3:38 12. YES Changes 90125 (1984) 6:20 13. SAXON Wheels Of Steel Live At Donington 1980 (1999) 5:33 14. QUEENSRYCHE Silent Lucidity The Best Of (2007) 5:48 15. ALLIANCE Road To Heaven Road To Heaven (2008) 3:52 16. WHITESNAKE Call On Me Good To Be Bad (2008) 5:01 17. WHITESNAKE All I Want All I Need Good To Be Bad (2008) 5:42 18. WHITESNAKE Good To Be Bad Good To Be Bad (2008) 5:13 19 MAGGIE BELL No Mean City Single (2008) 3:59 20. CLIMAX BLUES Gotta Have More Love The River Sessions (2005) 4:40 BAND 21. JOHN MARTYN Look At The Girl The Apprentice (2007) 4:34 22. -

Steve-Harris-The-Clairvoyant-Text

Índice Cómo leer este libro Retrato de un visionario Biografía acotada de Steve Harris Dave «Lights» Beazley ¡Steve le tiene terror a los fantasmas! Lauren Harris Mi papá trajo a Eddie en lugar de un payaso para uno de mis cumpleaños John Miles Steve Harris lee el foro del IMOC Keith Wilfort Todos creímos que Steve había perdido el juicio… Slaven Bilić Steve intentó convencerme de dirigir el West Ham Marty Moore Fui el primer nativo de la etnia Cree en agradecerle a Steve por escribir la canción Run to the Hills Dean Karr Hice una primera edición de Rock in Rio, aunque era Steve el que tenía la última palabra Steve «Loopy» Newhouse Steve iba siempre al baño antes de subirse al escenario Mike Kemp Utilizamos un pequeño truco para crear el sonido de bajo de Steve Harris Kanisa Atcharawatchala Steve Harris me hizo «orejas de conejo» en la foto que nos sacamos Markus Grosskopf Steve Harris fue quien guio sus destinos al sitial de grandeza donde se encuentran hoy Dennis Stratton Iron Maiden le pertenece exclusivamente a Steve Tony Newton Steve usaba una gorra y ocultaba en ella su pelo a modo de disfraz mientras filmaba nuestras presentaciones Toni Bulić Steve esperaba verme casi siempre en primera fila IRON MAIDEN – PÁGINAS MISTERIOSAS Paul «Mad Mac» Cairns y Strange World Solíamos ir a comer a la casa de la nona de Steve Keith Fisher (Beckett) Quién sabe, tal vez Steve anda corto de dinero Leah Gibbo Seki Steve ha leído todas mis cartas Paul Di’Anno Steve solía tener dolores de cabeza Rasmus Stavnsborg Steve se encandalizó por mis comentarios -

Up the Irons Vocals: Jos Severens Guitar: Sam Lemmens Guitar: Laurent Schijns Bass: Joey Bruers Drums: Tom Heijnen

Up The Irons Vocals: Jos Severens Guitar: Sam Lemmens Guitar: Laurent Schijns Bass: Joey Bruers Drums: Tom Heijnen www.UpTheIrons.nl Bio English Up The Irons is a well-known name in both the Iron Maiden realm as in “tribute-land” worldwide. Packing more than 15 years of experience, the band has done loads of shows everywhere in the world. Up The Irons consists of five very experienced Maiden maniacs, which is a guarantee for an explosive, high-energy performance. All the Iron Maiden blockbuster hits, combined with other fan-favourites, makes Up The Irons the ultimate Iron Maiden Tribute band for both the casual rock-fan as well as the hardcore, rabid Maiden fans that the bandmembers are themselves. Make sure to witness the best you can get, and maybe Eddie will join you for a snack as well Some examples of the more memorable shows are tours with Paul Di’Anno, playing Graspop Metal Meeting in 2006 and 2015 (for an estimated crowd of 25.000 metal maniacs!), touring Italy, France, Belgium, Germany and the UK besides Holland, being supported by Lauren Harris and many more. Not by any means downplaying the fact that the band still massively enjoys playing gigs anywhere, anytime in any country! Highlights: Up The Irons was founded in 1999 in Tilburg, the Netherlands. They have toured with former Iron Maiden singer Paul Di’Anno as a special guest to their shows, and Dennis Stratton (guitarist on the first Iron Maiden album) played a full set with Up The Irons on the Maiden Day 2016.