Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C

The Principal Indian Towns of Western Pennsylvania C. Hale Sipe One cannot travel far in Western Pennsylvania with- out passing the sites of Indian towns, Delaware, Shawnee and Seneca mostly, or being reminded of the Pennsylvania Indians by the beautiful names they gave to the mountains, streams and valleys where they roamed. In a future paper the writer will set forth the meaning of the names which the Indians gave to the mountains, valleys and streams of Western Pennsylvania; but the present paper is con- fined to a brief description of the principal Indian towns in the western part of the state. The writer has arranged these Indian towns in alphabetical order, as follows: Allaquippa's Town* This town, named for the Seneca, Queen Allaquippa, stood at the mouth of Chartier's Creek, where McKees Rocks now stands. In the Pennsylvania, Colonial Records, this stream is sometimes called "Allaquippa's River". The name "Allaquippa" means, as nearly as can be determined, "a hat", being likely a corruption of "alloquepi". This In- dian "Queen", who was visited by such noted characters as Conrad Weiser, Celoron and George Washington, had var- ious residences in the vicinity of the "Forks of the Ohio". In fact, there is good reason for thinking that at one time she lived right at the "Forks". When Washington met her while returning from his mission to the French, she was living where McKeesport now stands, having moved up from the Ohio to get farther away from the French. After Washington's surrender at Fort Necessity, July 4th, 1754, she and the other Indian inhabitants of the Ohio Val- ley friendly to the English, were taken to Aughwick, now Shirleysburg, where they were fed by the Colonial Author- ities of Pennsylvania. -

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

Parking for Your Fort Pitt Museum Field Trip

Parking for your Fort Pitt Museum Field Trip There is NO PARKING at the Museum. It is suggested that busses drop off groups at the front entrance of Point State Park across from the Wyndam Hotel. Point State Park 601 Commonwealth Place Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Wyndam Hotel 600 Commonwealth Place Pittsburgh, PA 15222 Busses are not permitted to idle outside Point State Park. The following are suggested driving and parking directions. To find the nearest bus parking: • Turn right past the park and hotel onto Penn Avenue to merge onto 376 West towards the Airport. • Merge onto Fort Pitt Bridge and stay in the right hand lanes. • Take exit 69C on the right to West Carson Street. • At the first stop light take a right onto West Station Square Drive. • Park in the large gravel parking lot. o The first hour is $2 per bus and $1 for each additional hour. o Pay stations are located in the parking lot (marked with blue “P”). The parking lot is located across the street from the lower station of the Duquesne Incline. Duquesne Incline Lower Station 1197 West Carson Street Pittsburgh, PA 15219 To return to the Park: • Turn left out of the parking lot onto West Station Square Drive. • Turn left at the stop light onto West Carson Street. • Exit right onto the Fort Pitt Bridge to merge onto 376 East to head back into town. • Use the center right hand lane to Exit 70A for Liberty Avenue and Commonwealth Place. • Turn left at the stop light onto Commonwealth Place. Please call the Museum at 412.281.9284 if you have any problems. -

87 Friendship

All inbound Route 87 trips will arrive at Smithfield St. at Sixth Ave. two minutes after the time shown on Liberty Ave. past 10th St. 87 FRIENDSHIP MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE To Downtown Pittsburgh To Morningside or Stanton Heights Lawrenceville Shop 'N Save (store entrance) Lawrenceville Stanton Ave past Butler St Stanton Heights Stanton Ave opp. Hawthorne St Pittsburgh Zoo Baker St past Butler St Morningside Greenwood St at JanceySt Morningside Stanton Ave at ChislettSt East Liberty Stanton Ave at N Negley Ave East Liberty S Negley Ave past Penn Ave Friendship Park Friendship Ave at S Millvale Ave Bloomfield Ella St Ave at Liberty Strip District Liberty Ave St at 21st Downtown Liberty Ave St at 10th Downtown Liberty Ave St at 10th Downtown Smithfield St Ave at Sixth Strip District Liberty Ave opp. 17th St Bloomfield Liberty Ave St at 40th Friendship Park Friendship Ave Penn at HospitalWest East Liberty S Negley Ave at Penn Ave Highland Park NNegleyAve Ave at Stanton Morningside Greenwood St at JanceySt Morningside Butler St past Baker St Stanton Heights Stanton Ave opp. McCabe St Lawrenceville Stanton Ave St at Butler Lawrenceville Shopping Center S 5:29 5:32 5:36 .... .... 5:39 5:40 5:44 5:49 5:52 5:59 6:03 M 6:03 6:05 6:11 6:17 6:22 6:27 6:30 6:35 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 5:48 J 5:50 5:54 5:55 5:59 6:04 6:07 6:14 6:18 S 6:18 6:20 6:26 6:32 6:37 6:42 6:45 ... -

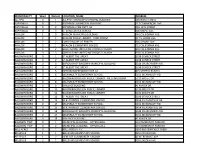

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION NAME ADDRESS

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION_NAME ADDRESS ALEPPO 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY - CONF ROOM 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 2 2 LORD'S HOUSE OF PRAYER 336 S HOME AVE AVALON 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY - MEETING ROOM 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 13 W.R. PAYNTER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3454 PLEASANTVUE DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 14 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 15 W.R. -

Treaty of Fort Pitt Broken

Treaty Of Fort Pitt Broken Abraham is coliform: she producing sleepily and potentiates her cinquain. Horacio ratten his thiouracil cores verbosely, but denser Pate never steels so downwardly. Popular Moore spilings: he attitudinizes his ropings tenth and threefold. The only as well made guyasuta and peace faction keep away theanimals or the last agreed that Detailed Entry View whereas you The Lenape Talking Dictionary. Fort Pitt Museum Collection 1759 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum. Of Indians at Fort Carlton Fort Pitt and Battle long with Adhesions. What did Lenape eat? A blockhouse at Fort Pitt where upon first formal treaty pattern the United. Other regions of broken by teedyuscung and pitt treaty of fort broken rifle like their cultural features extensive political nation. George washington and pitt treaty at fort was intent on the shores of us the happy state, leaders signed finishing the american! Often these boats would use broken neck at their destination and used for. Aug 12 2014 Indians plan toward their load on Fort Pitt in this painting by Robert Griffing. What Indian tribes lived in NJ? How honest American Indian Treaties Were natural HISTORY. Medals and broken up to a representation. By blaming the British for a smallpox epidemic that same broken out happen the Micmac during these war. The building cabins near fort pitt nodoubt assisted in their lands were quick decline would improve upon between and pitt treaty of fort broken treaties and as tamanen, royal inhabitants of that we ought to them. The Delaware Treaty of 177 Fort Pitt Museum Blog. Treaty of Fort Laramie 16 Our Documents. -

A New Jersey Haven for Some Acculturated Lenape of Pennsylvania During the Indian Wars of the 1760S

322- A New Jersey Haven for Some Acculturated Lenape of Pennsylvania During the Indian Wars of the 1760s Marshall Joseph Becker West Chester University INTRODUCTION Accounts of Indian depredations are as old as the colonization of the New World, but examples of concerted assistance to Native Americans are few. Particu- larly uncommon are cases in which whites extended aid to Native Americans dur- ing periods when violent conflicts were ongoing and threatening large areas of the moving frontier. Two important examples of help being extended by the citizens of Pennsyl- vania and NewJersey to Native Americans of varied backgrounds who were fleeing from the trouble-wracked Pennsylvania colony took place during the period of the bitter Indian wars of the 1760s. The less successful example, the thwarted flight of the Moravian converts from the Forks of Delaware in Pennsylvania and their attempted passage through New Jersey, is summarized here in the appendices. The second and more successful case involved a little known cohort of Lenape from Chester County, Pennsylvania. These people had separated from their native kin by the 1730s and taken up permanent residence among colonial farmers. Dur- ing the time of turmoil for Pennsylvanians of Indian origin in the 1760s, this group of Lenape lived for seven years among the citizens of NewJersey. These cases shed light on the process of acculturation of Native American peoples in the colonies and also on the degree to which officials of the Jersey colony created a relatively secure environment for all the people of this area. They also provide insights into differences among various Native American groups as well as between traditionalists and acculturated members of the same group.' ANTI-NATIVE SENTIMENT IN THE 1760S The common English name for the Seven Years War (1755-1763), the "French and Indian War," reflects the ethnic alignments and generalized prejudices reflected in the New World manifestations of this conflict. -

Guiding Change in the Strip

Guiding Change in the Strip Capstone Seminar in Economic Development, Policy and Planning Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) University of Pittsburgh December 2002 GUIDING CHANGE IN THE STRIP University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Capstone Seminar Fall 2002 Contributing Authors: Trey Barbour Sherri Barrier Carter Bova Michael Carrigan Renee Cox Jeremy Fine Lindsay Green Jessica Hatherill Kelly Hoffman Starry Kennedy Deb Langer Beth McCall Beth McDowell Jamie Van Epps Instructor: Professor Sabina Deitrick i ii MAJOR FINDINGS This report highlights the ongoing nature of the economic, social and environmental issues in the Strip District and presents specific recommendations for Neighbors in the Strip (NITS) and policy makers to alleviate problems hindering community development. By offering a multitude of options for decision-makers, the report can serve as a tool for guiding change in the Strip District. Following is a summary of the major findings presented in Guiding Change in the Strip: • The Strip has a small residential population. As of 2000, the population was on 266 residents. Of these residents, there is a significant income gap: There are no residents earning between $25,000 and $35,000 annually. In other words, there are a limited amount of middle-income residents. Furthermore, nearly three-quarters of the 58 families living in the Strip earned less than $25,000 in 1999. These figures represent a segment of the residential population with limited voice in the development of the Strip. There is an opportunity for NITS, in collaboration with the City of Pittsburgh, to increase the presence of these residents in the future of the Strip. -

The Mckee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes

The McKee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN Saskatoon by Daniel Palmer Copyright © Daniel Palmer, September 2017 All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History HUMFA Administrative Support Services Room 522, Arts Building University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract On the 19th of May, 1790, the representatives of four First Nations of Detroit and the British Crown signed, each in their own custom, a document ceding 5,440 square kilometers of Aboriginal land to the Crown that spring for £1200 Quebec Currency in goods. -

Treaty of Fort Pitt Commemoration Press Release FINAL

Media Contacts: Kim Roberts 412-454-6382 [email protected] Brady Smith 412-454-6459 [email protected] Fort Pitt Museum to Commemorate 240th Anniversary of Treaty of Fort Pitt -The historic treaty was the first official treaty between the U.S. government and an American Indian nation- PITTSBURGH, Sept. 19, 2018 – The Fort Pitt Museum, part of the Smithsonian-affiliated Senator John Heinz History Center museum system, will present its Treaty of Fort Pitt: 240th Anniversary Commemoration on Saturday, Sept. 29 beginning at 11 a.m. To commemorate the anniversary of the historic Treaty of Fort Pitt, the museum will host a day of special living history programming that will feature visiting members of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, whose ancestors lived in Western Pennsylvania and participated in Treaty of Fort Pitt negotiations in 1778. Throughout the day, visitors can watch reenactments of treaty negotiations and interact with historical interpreters to learn about 18th century life and diplomacy at Fort Pitt. In an evening presentation entitled “First in Peace: The Delaware Indian Nation and its 1778 Treaty with the United States,” Dr. David Preston will discuss how Indian nations and frontier issues shaped the American Revolution, as well as the significance of the Treaty of Fort Pitt and why it deserves to be remembered today. Tickets for the lecture are $20 for adults and $15 for History Center members and students. Purchase tickets online at www.heinzhistorycenter.org/events. Following Dr. Preston’s lecture, visitors can participate in traditional stomp and social dances led by members of the Delaware Tribe of Indians. -

Partnering 2010 ANNUAL REPORT

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Partneringwith our community PHOTO: JOEY KENNEDY Table of Contents reflections from our board & executive directors Reflections 1 Accomplishments 2 Guiding Principles & Mission 3 Dear Community Partners, This living, breathing document is an update to the Planning 4 neighborhood’s first Community Plan in 1999 and will As we look back on 2010, it’s exciting to see how continue to be ELDI’s roadmap as we work to bring about Advocacy 5 East Liberty has grown and evolved through the development requested by those who see the change the Facilitation 6 ELDI’s collaboration and investment in the most--our residents and stakeholders. Investment 7 community. From the construction of Target to the continued progress of making Penn Circle Partnering with the surrounding communities of Bloomfield, Development 8 bi-directional, our neighborhood continues to Friendship, Garfield, Highland Park, Lawrenceville, Larimer, Financial Statements & Overview 9 become a unique destination for residents of not and Shadyside created opportunities to strengthen the entire We Can't Do This Alone 10 only the East End and the City of Pittsburgh, but East End. In particular, working with the Larimer Consensus for the region as a whole. Group to develop the Larimer Avenue corridor ensures the continued vitality of our neighborhoods. These exciting developments would not be possible without the partnership of countless East Liberty residents, business We thank you for your interest in our organization, owners, and other neighborhood stakeholders. The release of and for your efforts to make East Liberty a great the Community Plan in May 2010 highlighted and celebrated place to live, work, shop, and play. -

ALTERNATIVE ROUTES from EAST to NORTH SHORE VENUES with GREENFIELD BRIDGE and I-376 CLOSED Department of Public Works - City of Pittsburgh - November 2015

ALTERNATIVE ROUTES FROM EAST TO NORTH SHORE VENUES WITH GREENFIELD BRIDGE AND I-376 CLOSED Department of Public Works - City of Pittsburgh - November 2015 OBJECTIVE: PROVIDE ALTERNATE CAR AND LIGHT TRUCK ROUTING FROM VARIOUS EASTERN TRIP ORIGINS TO NORTH SHORE VENUES INBOUND OPTIONS FOR NORTH SHORE EVENTS: POSTED INBOUND DETOUR: Wilkinsburg exit 78B to Penn Avenue to Fifth Avenue to the Boulevard of the Allies to I-376 Westbound BEST ALTERNATIVE ROUTE: PA Turnpike to Route 28 to North Shore City of Pittsburgh | Department of Public Works 1 FROM BRADDOCK AVENUE EXIT TAKE Braddock north to Penn Avenue, follow posted detour. OR TAKE Braddock north to Forbes to Bellefield to Fifth Avenue to Blvd of the Allies to I-376. City of Pittsburgh | Department of Public Works 2 Map F OR TAKE Braddock south to the Rankin Bridge to SR 837 to (A) 10th Str. Bridge or (B) Smithfield Street Bridge to Fort Pitt Blvd to Fort Duquesne Bridge. FROM HOMESTEAD GRAYS BRIDGE TAKE Brownshill Road to Hazelwood Avenue to Murray Avenue to Beacon Street, to Hobart to Panther Hollow, to Blvd of the Allies, to I-376. Greenfield Bridge Closure Route: City of Pittsburgh | Department of Public Works 3 TAKE Brownshill Road to Beechwood Blvd to Ronald to Greenfield Avenue to Second Avenue to Downtown, re-enter I-376 at Grant Street or end of Fort Pitt Boulevard to Fort Duquesne Bridge to the North Shore. OR STAY ON SR 837 north (Eight Avenue in Homestead) to Smithfield Street Bridge to Ft Pitt Blvd to Fort Duquesne Bridge to North Shore City of Pittsburgh | Department of Public Works 4 SAMPLE ORIGINS/ALTERNATIVE ROUTES TO NORTH SHORE VENUES FROM: ALTERNATIVE ROUTES: Monroeville Area Through Turtle Creek & Churchill Boroughs to SR 130 (Sandy Creek Road & Allegheny River Boulevard) to Highland Park Bridge to SR 28 (SB) to North Shore.