Procedural Justice and the Risks of Consumer Voting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Little More Conversation a Little Less Action

A Little More Conversation A Little Less Action Speech given by Andrew G Haldane, Chief Economist, Bank of England Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy Conference 31 March 2017 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Shiv Chowla, Jeremy Franklin, Jonathan Fullwood, Chloe Gilbert, Leanne Leahy, Michael McLeay, Michael McMahon, Sam McPhilemy, Chris Peacock and Paul Robinson for their help in preparing this text. I would like to thank Mike Anson, Tom Belsham, James Benford, Rachel Botsman, Nida Broughton, Kristin Forbes, Keir Haldane, John Lewis, Clare Macallan, Mike Peacock and Eryk Walczak for comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches It is a great pleasure to be here at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco conference on “Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy”. I am grateful to my old friend John Williams, President of the San Francisco Fed, for the invitation. And for one night only, John, where better to channel my inner-Elvis.1 Back in 2004, Benoit Mandelbrot observed: “So limited is our knowledge that we resort, not to science, but to shamans. We place control of the world’s largest economy in the hands of a few elderly men, the central bankers”.2 You could quibble with the detail here – a few central bankers these days are women and a few are not old. But the general sentiment is not one which would be entirely out of place today. It is not difficult to see why. -

BHSA Newsletter

BHSA Newsletter Autumn Term 2019 Edition 05 Welcome Welcome to our October 2019 Newsletter. We have had an incredibly busy and positive start to this aca- demic year at BHSA . I hope you enjoy reading about some of the many opportunities the girls have em- braced so far this term. It is virtually impossible to New junior school council select any favourites, but a real highlight in the Sen- ior School was welcoming Deana Puccio form The Rap Project UK to BHSA. Her presentations to all girls from Years 7 to 13 were both powerful and in- spiring, delivering an important message to every single one of us. The girls are still talking about her visit. This was made possible through funding from the GDST and we are very proud to be part of this movement in girls’ education. The highlights in the Junior School are too many to mention, but the new art work and displays throughout the Juniors show the wonderful end products from the numerous col- laborative, creative workshops this term. As always, the girls never cease to amaze me with their confi- dence, talents and determination. This was seen in abundance at our recent Open Events and there were many proud moments on receiving the glow- ing feedback about our girls from the record num- bers of visitors. I hope you enjoy a relaxing half term break and I look forward to welcoming the girls back on the 4th November. Thank you for your continued support. Rebecca Mahony Sophie the T-Rex came to visit! Did you hear about the dinosaurs visiting our school? Sophie the T- Rex came to visit! Our infant girls were immersed in a Jurassic world where they learnt paleontological and archaeological skills, and eve- rybody had a superb (and a little bit of a scary) time! Wow! What an exciting morning KS1 and Reception pupils had on Tuesday 24th September. -

Unravelling the New Plebiscitary Democracy: Towards a Research Agenda

Government and Opposition (2021), 56, 615–639 doi:10.1017/gov.2020.4 . ARTICLE Unravelling the New Plebiscitary Democracy: Towards a Research Agenda Frank Hendriks* https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms Tilburg University, Department of Public Law and Governance, Tilburg, the Netherlands *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (Received 2 August 2019; revised 25 November 2019; accepted 17 January 2020; first published online 20 March 2020) Abstract Pushed by technological, cultural and related political drivers, a ‘new plebiscitary democ- racy’ is emerging which challenges established electoral democracy as well as variants of deliberative democracy. The new plebiscitary democracy reinvents and radicalizes longer-existing methods (initiative, referendum, recall, primary, petition, poll) with new tools and applications (mostly digital). It comes with a comparatively thin conceptualiza- tion of democracy, invoking the bare notion of a demos whose aggregated will is to steer actors and issues in public governance in a straight majoritarian way. In addition to unrav- , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at elling the reinvented logic of plebiscitary democracy in conceptual terms, this article fleshes out an empirically informed matrix of emerging formats, distinguishing between votations that are ‘political-leader’ and ‘public-issue’ oriented on the one hand, and ‘inside-out’ and ‘outside-in’ initiated on the other hand. Relatedly, it proposes an agenda for systematic research into the various guises, drivers and implications of the new plebis- citary democracy. Finally, it reflects on possible objections to the argumentation. 28 Sep 2021 at 17:33:14 , on Keywords: new plebiscitary democracy; democratic transformation; electronic voting; digital democracy; populism Vox populi redux 170.106.35.229 In May 2018, the Spanish left-wing political party Podemos organized a digital party referendum, as they called it, on its leadership. -

Sir David Attenborough 14 Consequences Of, and Cures For, Unsustainable Human Population and Consumption Levels

ISSN 2053-0420 (Online) for a sustainable future Population Matters Magazine Issue 29 Summer 2016 Water shortages to affect billions What does Brexit say about attitudes to population? London set to grow by 1.2 million Population Matters Magazine - Issue 29 Population Matters Magazine - Issue 29 Contents The roots of mass migration Simon Ross, Chief Executive The roots of mass migration 3 Magazine Giving women choices in Guatemala 4 This magazine is printed using vegetable-based inks on Legacy giving: Pass it on 5 100 per cent recycled paper. If you are willing to receive the magazine by email, which reduces our costs and Public concern, though, is reinforced by the wider Roger Martin: Appreciation of his term as Chair 5 helps the environment, please contact the Finance and global picture. Membership Manager. Interview with a patron: Aubrey Manning 8 Just days before the referendum, the United Nations Additional copies are available on request; a donation reported that a record 65m people globally were either Celebrating 25 Years: Looking back and looking forward 10 is appreciated. Population Matters does not necessarily refugees, asylum seekers or internally displaced, endorse contributions nor guarantee their accuracy. an increase of 5m in just a year. These dry figures Spotlight on a team member: Graham Tyler 12 Interested parties are invited to submit, ideally by email, translate to the persistent suffering and frequent 126 miles for us all 13 material to be considered for inclusion, including articles, fatalities of those seeking to enter Europe from Africa reviews and letters. Subjects may include the causes and and the Middle East. -

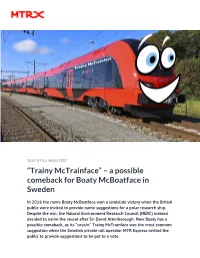

“Trainy Mctrainface” – a Possible Comeback for Boaty Mcboatface in Sweden

2017-07-14 06:00 CEST “Trainy McTrainface” – a possible comeback for Boaty McBoatface in Sweden In 2016 the name Boaty McBoatface won a landslide victory when the British public were invited to provide name suggestions for a polar research ship. Despite the win, the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) instead decided to name the vessel after Sir David Attenborough. Now Boaty has a possible comeback, as its “cousin” Trainy McTrainface was the most common suggestion when the Swedish private rail operator MTR Express invited the public to provide suggestions to be put to a vote. In May 2017, the newspaper Metro and MTR Express asked Metro’s readers to submit name suggestions for four of MTR Express’ trains. The most frequent proposal by far was “Trainy McTrainface”, a hats off to Boaty McBoatface. The name was the people’s overwhelming choice in an online naming contest organized by the NERC, for a £200 million polar research vessel that attracted global attention last year. However, Science Minister Jo Johnson suggested there were "more suitable" names and the NERC decided to instead name the ship after the world-renowned naturalist and broadcaster, Sir David Attenborough. To partially accommodate the wishes of the public the name Boaty McBoatface was given to a robotic undersea research vessel. Now Boaty McBoatface has a chance to make a comeback as Trainy McTrainface, one of top eight submitted names that the public can now vote for to name an MTR Express train. The vote takes place on Metro’s website and closes on July 17th . MTR-koncernen, med bas i Hongkong, är ett av världens ledande företag inom spårbunden kollektivtrafik och infrastruktur. -

European Petrophysics Consortium Annual Report 2016

EPC European Petrophysics Consortium European Petrophysics Consortium L EICESTER • MONTPELLIER • AACHEN Annual Report 2016 Dr Johanna Lofi and Chris Nixon having their work filmed during the IODP Expedition 364 Onshore Science Party EPC Annual Report 2016 2016 has been another busy year for the European Petrophysics Consortium (EPC), starting with preparation and participation in the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition 357: Atlantis Massif Serpentinization & Life Onshore Science Party (OSP). The remainder of the year was dominated by implementation of IODP Expedition 364: Chicxulub K-Pg Impact Crater with the offshore phase in the spring, and the OSP in the fall. EPC personnel have also been involved in enhancing the consortium’s equipment and facilities, as well as participating in a range of education and outreach activities throughout the year. Planning for future IODP expeditions has continued, including scoping the downhole logging and core physical properties programs for IODP Expeditions 373: Antarctica Cenozoic Paleoclimate, 377: Arctic Ocean Paleoceanography, and more recently 381: Corinth Active Rift Development. EPC continues to provide Contents operational support and petrophysical expertise to the wider IODP community through representation of Mission Specific Platform (MSP) Updates .................... 2 European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling Expedition 357: Atlantis Massif Serpentinization & (ECORD) Science Operator (ESO) at the IODP Science Life (P758) ............................................................... -

Session Chair Theme 5 Generating Information from Data

Marine Physics and Ocean Climate Generating Information from Data Marine Autonomy & Technology Showcase 2019 Eleanor Frajka-Williams Theme 5: Generating information from Data Generating information that meets end-user needs from the data collected by MAS is the ultimate goal of deploying the system. This theme will explore novel methods of generating information products from MAS gathered data. Presentations should explore (but not be limited to) the utility of Machine Learning and AI, Data Processing, GUIs, augmented realities. Examples of real world information use should be explored. Examples as a scientific end user National Oceanography Centre BBC Scales dissipation Internal waves eddies Basin scale Tools AUVs gliders satellites ships Scientific objectives • Studying ocean circulation with influence on climate – primarily physical processes BBC • Using observations, I focus on questions where we can move our understanding forward – often process studies (where autonomous platforms shine) www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-35074501 Fernandez-Castro et al. (in revision) National Oceanography Centre Deep ocean warming: Why is Antarctic Bottom Water warming? Autosub Long Range aka Boaty McBoatface DynOPO project (NERC): University of Southampton, British Antarctic Survey & National Oceanography Centre National Oceanography Centre Spatial mapping of physical processes Naveira Garabato et al. (2019) National Oceanography Centre Ocean energetics – where do mesoscale eddies die? underwater Gliders MerMEED project (NERC): University of Southampton, the National Oceanography Centre Why care weWhy National Oceanography Centre Mesoscale eddies Satellites Glider sections Rossby number Fernandez-Castro et al. (in revision) Unwrapping / rewrapping data using auxiliary measurements (satellites) Why care weWhy National Oceanography Centre Marine Physics and Ocean Climate Generating information that meets end-user needs from the data collected by MAS is the ultimate goal of deploying the system. -

SICM-Weekly-Newslett

INSIGHTS For the Mainstream Investor @sicmgmt Week ending May 13, 2016 Edition 142 BIG OIL’S CLIMATE PINCER THIS WEEK IN NUMBERS MOVEMENT? 390,900 is the estimated number of plants known to Downstream: Oil and gas refiners are under Upstream and downstream, big oil science. pressure to use a carbon price, pushing the cost of is being squeezed production higher. 80,000 Upstream: The Obama administration istightening Africans per year die from yellow fever. controls on the US fracking industry, requiring Meanwhile, the catastrophic fires in Western Canada this week triggered a discussion of producers to reduce methane leaks. Rules were 260 finalized this week by the EPA. Meanwhile, several whether or not climate change contributed to or percent is the increase in home insurance oil majors are abandoning oil rights in the arctic even exacerbated the fires. premiums in Oklahoma, following an increase as crude oil prices are plummeting, forcing oil in earthquakes (possibly linked to fracking). READ MORE (subscription required) companies to cut spending. 149 @SICMGMT TWEET OF THE WEEK chiefdoms in Sierra Leone are expected to receive solar power within the next 18 months. S&P Warns of Climate Risks to Financial Sector http://www.bna.com/sp-warns- climate-n57982070751/ … via @bloombergbna 29 percent of senior officials in US finance WE’RE WATCHING and insurance are women. Top palm oil producer, IOI, sued Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) over deforestation allegations. The company was suspended by RSPO last month over allegations that it had deforested 8.5 Indonesian rainforests. The suit claims that the company did no wrong and the RSPO had no right to trillion Yen (USD 76 billion) of Japanese coal suspend its sustainability certification. -

Production of Teaching Resources for the Polar Explorer Programme

Invitation to Tender: Production of teaching resources for the Polar Explorer programme Summary Created for schools who are keen to raise aspirations and attainment in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), the Polar Explorer Programme aims to inspire the next generation of scientists and engineers. https://www.stem.org.uk/welcome-polar-explorer-programme As part of this initiative we are seeking consultants to undertake the development of individual teaching resources directly relevant to the curriculum for students aged 7- 12 in STEM subjects (or computing), which should be focused around at least one of the themes of the Polar Explorer Programme. Consultants may bid for one or more of the following resources: 1 x Transition Project – A resource that can be used with 10-12 year olds as they move from primary to secondary/post-primary. 1 x STEM Career Booklet – Looking at the various careers of those who work on polar vessels as well as at polar research stations, and those involved in the planning and logistics of the trip. 1 x Polar Explorer ‘Cook Book’ – A guide to polar food science including nutrition, recipes, preservation, storage and transport. 1. Background In 2014 the Government announced a £200 million investment for a new polar research ship. The RRS Sir David Attenborough will enable world-leading research in Antarctica and the Arctic for the next 25 years. Fully equipped with the latest instrumentation for the purposes of carrying out research in polar-regions, this vessel will have improved ice strengthened capability and greater endurance over existing polar research vessels. -

Boaty Mcboatface Meets Roboboat 2016

Daytona Beach Homeschoolers 1 Boaty McBoatFace Meets RoboBoat 2016 Abigail Butka, Nick Serle 1 completely straight. This is shown in figure 1. The yellow Abstract— This document describes the Daytona Beach line is the ideal track, the purple line is the actual track of Homeschooler’s entry to the RoboBoat competition. Topics in the vehicle, the green line is the direction the boat is this document include: the new vehicle name, lessons learned heading, and the red line is the direction the compass is from RoboBoat 2015, the overall strategy to accomplish the reading. competition tasks, and the team’s outreach efforts. New hardware this year includes: a tethered submersible, new thrusters, and hydrophones. Keywords— Autonomous, RoboBoat, Sonar, PixHawk, APM Rover I. INTRODUCTION Our first entry to the RoboBoat competition was in 2015. We entered the competition to learn more about GPS navigation. Due to the number of challenges in the RoboBoat competition, it was difficult to achieve all of the tasks. We chose to focus on navigation and vision Fig. 1 Telemetry crabbing in final run. processing. We did not have hydrophones so we did not attempt to locate the pinger. Despite many mistakes and malfunctions, our performance was better than expected. The boat has an internal and external compass and the We finished in 4th place overall. boat was programmed to use the external compass, but because of a bug in Mission Planner [2], the team was A. The New Vehicle Name unknowingly using the internal compass. The internal In 2016 the British Navy had an online poll to name their compass was near the motors and could have been affected new Artic research vessel. -

CAB 288 November 2020

INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION MARITIME KNOWLEDGE CENTRE (MKC) “Sharing Maritime Knowledge” CURRENT AWARENESS BULLETIN NOVEMBER 2020 www.imo.org Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) [email protected] Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) About the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) The aim of the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is to provide a digest of news and publications focusing on key subjects and themes related to the work of IMO. Each CAB issue presents headlines from the previous month. For copyright reasons, the Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) contains brief excerpts only. Links to the complete articles or abstracts on publishers' sites are included, although access may require payment or subscription. The MKC Current Awareness Bulletin is disseminated monthly and issues from the current and the past years are free to download from this page. Email us if you would like to receive email notification when the most recent Current Awareness Bulletin is available to be downloaded. The Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is published by the Maritime Knowledge Centre and is not an official IMO publication. Inclusion does not imply any endorsement by IMO. Table of Contents IMO NEWS & EVENTS ............................................................................................................................ 2 UNITED NATIONS ................................................................................................................................... 4 CASUALTIES........................................................................................................................................... -

Investigating Icy Waters with Boaty Mcboatface

Thought Leadership the abyssal waters across most of the globe. These waters have warmed in recent decades, and we don’t really know why – but we need to figure it out, so that we can BAS: Investigating better predict how it will change in future. This matters for several reasons, including the global heat budget and sea level rise. icy waters with The DynOPO project was created by scientists at the University of Southampton, BAS and the USA to study these dense waters as they flow northward from the Boaty McBoatface Antarctic into the Atlantic Ocean, and what happens to them when they cross an Oceans are not only filled with many weird and wonderful creatures, underwater mountain chain called the South but they can also slow down climate change – storing human-produced Scotia Ridge. We believe that the contorted carbon and heat in their oceanic depths. Understanding how this process pathways the water takes as it flows over and around these mountains leads to a lot happens is vital to predicting the impact climate change will have over of mixing, and that this mixing might change the coming years. Professor Mike Meredith, science leader at the British over time. We hope to find out exactly how Antarctic Survey, focuses on this area – investigating dense waters as and why this happens, and what it means they flow from Antarctica into the Atlantic Ocean, as a participant in the for the role that these deep waters play in climate change. Dynamics of the Orkney Passage Outflow (DynOPO) project. You recently lived and worked on board the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) research ship ack in 2014, construction began NERC’s BAS.