Advisory Opinion 21-01 on the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act Scope of Preemption Provision January 8, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUDICIAL ETHICS ADVISORY OPINION SUMMARIES May-June

JUDICIAL ETHICS ADVISORY OPINION SUMMARIES May-June 2019 Alaska Advisory Opinion 2019-1 http://www.acjc.alaska.gov/advopinions.html#2019-01 Disqualification: Former public defender A former public defender is disqualified from matters involving former clients for 2 years after becoming a judge unless the disqualification is waived but is not disqualified from cases against the state or a municipality or from cases in which the public defender’s office appears. Arizona Advisory Opinion 2019-1 http://www.azcourts.gov/Portals/137/ethics_opinions/2019/ethics%20opinion%2019-01.pdf Unsolicited donation for problem-solving court incentives A court may accept unsolicited monetary donations from a charitable organization to purchase incentives such as gift cards and bus passes for participants in problem-solving courts. Florida Advisory Opinion 2019-17 http://www.jud6.org/LegalCommunity/LegalPractice/opinions/jeacopinions/2019/2019- 17.html Disqualification: Parents’ former law firm, parents’ tenant A judge is not required to disqualify from cases involving her lawyer-parent’s former law firm. A judge is not automatically recused from cases involving a law firm that leases a building from her parent if her parent’s interest can be classified as de minimis. Florida Advisory Opinion 2019-18 http://www.jud6.org/LegalCommunity/LegalPractice/opinions/jeacopinions/2019/2019- 18.html Writing book A judge may write a book about family law courts and the mental health issues sometimes associated with them, specifically, the “warning signs” that judges and litigants should be concerned about, and may actively promote the book as long as he does not use the prestige of office to promote the book and the judge, his judicial assistant, and members of his family do not sell the book to any member of the Bar. -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 5/Friday, January 8, 2021/Notices

1518 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 5 / Friday, January 8, 2021 / Notices program issues and concerns; propose DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND medical education; appropriation levels policy changes using the varying levels HUMAN SERVICES for certain programs under Title VII of of expertise represented on the Council the PHS Act; and deficiencies in to advise on specific program areas; Health Resources and Services databases of the supply and distribution updates from clinician workforce Administration of the physician workforce and experts; and education and practice postgraduate programs for training Meeting of the Council on Graduate improvement in the training Medical Education physicians. COGME submits reports to development of primary care clinicians. the Secretary of HHS; the Senate More general items may include: AGENCY: Health Resources and Services Committee on Health, Education, Labor Presentations and discussions on the Administration (HRSA), Department of and Pensions; and the House of current and emerging needs of health Health and Human Services (HHS). Representatives Committee on Energy workforce; public health priorities; ACTION: Notice. and Commerce. Additionally, COGME healthcare access and evaluation; encourages entities providing graduate NACNHSC-approved sites; HRSA SUMMARY: In accordance with the medical education to conduct activities priorities and other federal health Federal Advisory Committee Act, this to voluntarily achieve the workforce and education programs that notice announces that the Council on recommendations of the Council. Since impact the NACNHSC. Graduate Medical Education (COGME or priorities dictate meeting times, be Council) will hold public meetings for advised that start times, end times, and Refer to the NACNHSC website listed the 2021 calendar year (CY). agenda items are subject to change. -

Early Dance Division Calendar 17-18

Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 1 September 9 – November 3 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes September 11 Class September 12 Class September 18 Class September 19 Class September 25 Class September 26 Class October 2 Class October 3 Class October 9 Class October 10 Class October 16 Class October 17 Class October 23 Class October 24 Class October 30 Last Class October 31 Last Class Wednesday Classes Thursday Classes September 13 Class September 14 Class September 20 Class September 21* Class September 27 Class September 28 Class October 4 Class October 5 Class October 11 Class October 12 Class October 18 Class October 19 Class October 25 Class October 26 Class November 1 Last Class November 2 Last Class Saturday Classes Sunday Classes September 9 Class September 10 Class September 16 Class September 17 Class September 23 Class September 24 Class September 30* Class October 1 Class October 7 Class October 8 Class October 14 Class October 15 Class October 21 Class October 22 Class October 28 Last Class October 29 Last Class *Absences due to the holiday will be granted an additional make-up class. Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 2 November 4 – January 22 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes November 6 Class November 7 Class November 13 Class November 14 Class November 20 No Class November 21 No Class November 27 Class November 28 Class December 4 Class December 5 Class December 11 Class December 12 Class December 18 Class December 19 Class December 25 No Class December 26 No Class January 1 No Class January 2 No Class January 8 Class -

Published Ethics Advisory Opinions (Guide, Vol. 2B, Ch

Guide to Judiciary Policy Vol. 2: Ethics and Judicial Conduct Pt. B: Ethics Advisory Opinions Ch. 2: Published Advisory Opinions § 210 Index § 220 Committee on Codes of Conduct Advisory Opinions No. 2: Service on Governing Boards of Nonprofit Organizations No. 3: Participation in a Seminar of General Character No. 7: Service as Faculty Member of the National College of State Trial Judges No. 9: Testifying as a Character Witness No. 11: Disqualification Where Long-Time Friend or Friend’s Law Firm Is Counsel No. 17: Acceptance of Hospitality and Travel Expense Reimbursements From Lawyers No. 19: Membership in a Political Club No. 20: Disqualification Based on Stockholdings by Household Family Member No. 24: Financial Settlement and Disqualification on Resignation From Law Firm No. 26: Disqualification Based on Holding Insurance Policy from Company that is a Party No. 27: Disqualification Based on Spouse’s Interest as Beneficiary of a Trust from which Defendant Leases Property No. 28: Service as Officer or Trustee of Hospital or Hospital Association No. 29: Service as President or Director of a Corporation Operating a Cooperative Apartment or Condominium No. 32: Limited Solicitation of Funds for the Boy Scouts of America No. 33: Service as a Co-trustee of a Pension Trust No. 34: Service as Officer or on Governing Board of Bar Association No. 35: Solicitation of Funds for Nonprofit Organizations, Including Listing of Judges on Solicitation Materials No. 36: Commenting on Legal Issues Arising before the Governing Board of a Private College or University No. 37: Service as Officer or Trustee of a Professional Organization Receiving Governmental or Private Grants or Operating Funds No. -

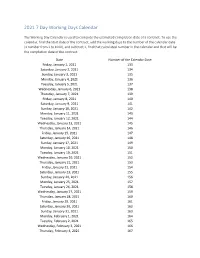

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

School News Important Dates Coming Soon Art & Basketball Shelton Hawkins, an Art Teacher at St

Charles County Public Schools It’s All About Teaching and Learning. School News Important Dates Coming Soon Art & Basketball Shelton Hawkins, an art teacher at St. Charles High Virtual plays set School, is on the cover of the Maurice J. McDonough High School January/February edition of is hosting a virtual play Friday, Jan. 8, and Shore Magazine, a publica- Saturday, Jan. 9. The drama department tion focused on the people and will stream “Game of Tiaras (one-act): lifestyle on the Eastern Shore. Stay-At-Home Edition” by Don Zolidis. A Easton native, Hawkins The show is set to stream virtually on Jan. spent time during quarantine 8-9. Interested viewers can access the link bettering his community with online at https://mhsdrama303.booktix. his creativity. Before 2020 com/. Check the website for updates. The kept people indoors, Hawkins drama department is also collecting com- combined his love of basketball munity donations on its website to support and art to start Play In Color, a production costs. Questions can be directed project that transforms outdoor to Jana Heyl, McDonough drama director, basketball courts into usable at [email protected]. works of art that foster a sense Westlake High School Westlake High of community. Read more on School is hosting two virtual events this Page 2. month. The drama department will stream “The Day the Internet Died” by Ian Mc- Wethy and Jason Pizzarello starting Jan. 15, and “Identity Play; or Who You Are If You Think You Are” by Jon Jory and Jason CCPS delivering meals to a neighborhood near you Pizzarello starting Jan. -

![Advisory Opinion of 25 February 2019 [Amended 4 March 2019 by Request]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6294/advisory-opinion-of-25-february-2019-amended-4-march-2019-by-request-826294.webp)

Advisory Opinion of 25 February 2019 [Amended 4 March 2019 by Request]

25 FÉVRIER 2019 AVIS CONSULTATIF EFFETS JURIDIQUES DE LA SÉPARATION DE L’ARCHIPEL DES CHAGOS DE MAURICE EN 1965 ___________ LEGAL CONSEQUENCES OF THE SEPARATION OF THE CHAGOS ARCHIPELAGO FROM MAURITIUS IN 1965 25 FEBRUARY 2019 ADVISORY OPINION TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs CHRONOLOGY OF THE PROCEDURE 1-24 I. EVENTS LEADING TO THE ADOPTION OF THE REQUEST FOR THE ADVISORY OPINION 25-53 II. JURISDICTION AND DISCRETION 54-91 A. Jurisdiction 55-62 B. Discretion 63-68 1. Whether advisory proceedings are suitable for determination of complex and disputed factual issues 69-74 2. Whether the Court’s response would assist the General Assembly in the performance of its functions 75-78 3. Whether it would be appropriate for the Court to re-examine a question allegedly settled by the Arbitral Tribunal constituted under UNCLOS Annex VII in the Arbitration regarding the Chagos Marine Protected Area 79-82 4. Whether the questions asked relate to a pending dispute between two States, which have not consented to its settlement by the Court 83-91 III. THE FACTUAL CONTEXT OF THE SEPARATION OF THE CHAGOS ARCHIPELAGO FROM MAURITIUS 92-131 A. The discussions between the United Kingdom and the United States with respect to the Chagos Archipelago 94-97 B. The discussions between the Government of the United Kingdom and the representatives of the colony of Mauritius with respect to the Chagos Archipelago 98-112 C. The situation of the Chagossians 113-131 IV. THE QUESTIONS PUT TO THE COURT BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 132-182 A. Whether the process of decolonization of Mauritius was lawfully completed having regard to international law (Question (a)) 139-174 1. -

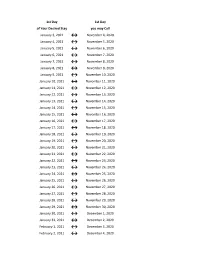

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

Pay Week Begin: Saturdays Pay Week End: Fridays Check Date

Pay Week Begin: Pay Week End: Due to UCP no later Check Date: Saturdays Fridays than Monday 7:30am week 1 December 10, 2016 December 16, 2016 December 19, 2016 December 30, 2016 week 2 December 17, 2016 December 23, 2016 December 26, 2016 week 1 December 24, 2016 December 30, 2016 January 2, 2017 January 13, 2017 week 2 December 31, 2016 January 6, 2017 January 9, 2017 week 1 January 7, 2017 January 13, 2017 January 16, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 2 January 14, 2017 January 20, 2017 January 23, 2017 January 21, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 1 January 30, 2017 February 10, 2017 week 2 January 28, 2017 February 3, 2017 February 6, 2017 week 1 February 4, 2017 February 10, 2017 February 13, 2017 February 24, 2017 week 2 February 11, 2017 February 17, 2017 February 20, 2017 March 3, 2017 week 1 February 18, 2017 February 24, 2017 February 27, 2017 ***1 Week Pay Period Transition*** week 1 February 25, 2017 March 3, 2017 March 6, 2017 March 17, 2017 week 2 March 4, 2017 March 10, 2017 March 13, 2017 week 1 March 11, 2017 March 17, 2017 March 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 week 2 March 18, 2017 March 24, 2017 March 27, 2017 week 1 March 25, 2017 March 31, 2017 April 3, 2017 April 14, 2017 week 2 April 1, 2017 April 7, 2017 April 10, 2017 week 1 April 8, 2017 April 14, 2017 April 17, 2017 April 28, 2017 week 2 April 15, 2017 April 21, 2017 April 24, 2017 week 1 April 22, 2017 April 28, 2017 May 1, 2017 May 12, 2017 week 2 April 29, 2017 May 5, 2017 May 8, 2017 week 1 May 6, 2017 May 12, 2017 May 15, 2017 May 26, 2017 week 2 May 13, 2017 May 19, 2017 May -

Advisory Opinion 2019-12

OPINION 2019-12 Issued October 4, 2019 Appointment of a Magistrate as an Eldercare Coordinator SYLLABUS: A probate court magistrate may not be appointed as an eldercare coordinator in addition to his or her duties as a judicial officer. The dual appointment of a probate court magistrate as an eldercare coordinator interferes with the official duties of the position of magistrate and leads to frequent disqualification. The dual appointment of a probate court magistrate as an eldercare coordinator raises questions as to the magistrate’s impartiality. This nonbinding advisory opinion is issued by the Ohio Board of Professional Conduct in response to a prospective or hypothetical question regarding the application of ethics rules applicable to Ohio judges and lawyers. The Ohio Board of Professional Conduct is solely responsible for the content of this advisory opinion, and the advice contained in this opinion does not reflect and should not be construed as reflecting the opinion of the Supreme Court of Ohio. Questions regarding this advisory opinion should be directed to the staff of the Ohio Board of Professional Conduct. 65 SOUTH FRONT STREET, 5TH FLOOR, COLUMBUS, OH 43215-3431 Telephone: 614.387.9370 Fax: 614.387.9379 www.bpc.ohio.gov HON. JOHN W. WISE RICHARD A. DOVE CHAIR DIRECTOR PATRICIA A. WISE D. ALLAN ASBURY VICE- CHAIR SENIOR COUNSEL KRISTI R. MCANAUL COUNSEL OPINION 2019-12 Issued October 4, 2019 Appointment of a Magistrate as an Eldercare Coordinator SYLLABUS: A probate court magistrate may not be appointed as an eldercare coordinator in addition to his or her duties as a judicial officer. -

Advisory Opinions and the Influence of the Supreme Court Over American Policymaking

ADVISORY OPINIONS AND THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPREME COURT OVER AMERICAN POLICYMAKING The influence and prestige of the federal judiciary derive primarily from its exercise of judicial review. This power to strike down acts of the so-called political branches or of state governments as repugnant to the Constitution — like the federal judicial power more generally — is circumscribed by a number of self-imposed justiciability doctrines, among the oldest and most foundational of which is the bar on advi- sory opinions.1 In accord with that doctrine, the federal courts refuse to advise other government actors or private individuals on abstract legal questions; instead, they provide their views only in the course of deciding live cases or controversies.2 This means that the Supreme Court will not consider whether potential legislative or executive ac- tion violates the Constitution when such action is proposed or even when it is carried out, but only when it is challenged by an adversary party in a case meeting various doctrinal requirements. So, if a legisla- tive coalition wishes to enact a law that might plausibly be struck down — such as the 2010 healthcare legislation3 — it must form its own estimation of whether the proposal is constitutional4 but cannot know for certain how the Court will ultimately view the law. The bar on advisory opinions is typically justified by reference to the separation of powers and judicial restraint: when courts answer le- gal questions outside the legal dispute-resolution process, they reach beyond the judicial role and assume a quasi-legislative character. But ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 See Flast v. -

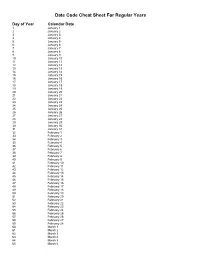

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April