Au.Artshub.Com | the Australian Arts Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leos Carax Chapter 2 116

Leos Carax Chapter 2 116 [This is a pre-publication version of chapter 2 of Leos Carax, by Fergus Daly and Garin Dowd] 2 Feux d’artifice: Les Amants du Pont-Neuf or the spectacle of vagrancy [D]o not allegory and the uncanny bring into play the same procedures: ambivalence, the double, the organic and non-organic, living/artificial body, fixation on sight and the anxiety of losing it, and above all dread of the fragmented body? (Buci-Glucksmann 1994: 166)1 Et n’oublions pas que si Carax donne parfois l’impression de faire un peu trop de cinéma dans ces films, c’est sans doute qu’il doit en faire à la place de tous les réalisateurs de sa génération qui n’en font pas assez. (Sabouraud 1991: 14)2 Between the completion of Mauvais Sang and the start of his next project Carax appeared in his second screen role, this time in the part of Edgar in Godard’s King Lear (1987). The circumstances whereby Godard came to sign a contract with the film’s Hollywood producers, Golan and Globus of Cannon, have become the stuff of legend, as has the story of how Norman Mailer stormed off the shoot and the part of Woody Allen as the Fool became limited to a few minutes of footage in the final cut. Of the roles taken by well-known non-actors (Mailer) or of actors also associated with other directorial projects (Allen) in the film, and whose names were deemed crucial by the producers, the role of Carax as Edgar is, paradoxically, the most integral. -

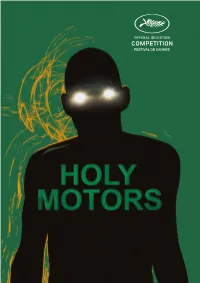

Holy Motors De Leos Carax, France-Allemagne, 2012, 115 Minutes Jacques Kermabon

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:08 p.m. 24 images Pour la beauté du geste Holy Motors de Leos Carax, France-Allemagne, 2012, 115 minutes Jacques Kermabon Visages du politique au cinéma Number 158, September 2012 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/67649ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Kermabon, J. (2012). Review of [Pour la beauté du geste / Holy Motors de Leos Carax, France-Allemagne, 2012, 115 minutes]. 24 images, (158), 51–51. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2012 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CANNES Holy Motors de Leos Carax Pour la beauté du geste par Jacques Kermabon ous l’avons tant aimé, Leos Carax. Qualifié de Rimbaud du cinéma N français avec Boy meets girl, il n’a pas renié cette filiation avec le titre de son deuxième opus Mauvais sang. Après les démêlés de la production des Amants du Pont-Neuf et malgré les fulgurances de Pola X, on parlera plutôt de saison en enfer. On craignait un peu ce retour. Nous avions tort. -

Strategies of Digital Surrealism in Contemporary Western Cinema by à 2018 Andrei Kartashov Bakalavr, Saint Petersburg State University, 2012

Strategies of Digital Surrealism in Contemporary Western Cinema By ã 2018 Andrei Kartashov Bakalavr, Saint Petersburg State University, 2012 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Chair: Dr. Catherine Preston Dr. Ronald Wilson Margaret Jamieson Date Defended: 27 April 2018 ii The thesis committee for Andrei Kartashov certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Strategies of Digital Surrealism in Contemporary Western Cinema Chair: Dr. Catherine Preston Date Approved: 27 April 2018 iii Abstract This thesis joins an ongoing discussion of cinema’s identity in the digital age. The new technology, which by now has become standard for moving images of any kind, has put into question existing assumptions and created paradoxes from a continuity between two different media that are, however, thought of as one medium. I address that problem from the perspective of surrealist film theory, which insisted on paradoxes and saw cinema as an art form that necessarily operated on contradictions: a quality that resonated with surrealism’s general aesthetic theory. To support my argument, I then analyze in some depth three contemporary works of cinema that possess surrealist attributes and employed digital technology in their making in a self-conscious way. Leos Carax’s Holy Motors, Pedro Costa’s Horse Money, and Seances by Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson and Galen Johnson all point to specific contradictions revealed by digital technology that they resolve, or hold in tension, in accordance with the surrealist notion of point sublime. -

Identities in Motion: Asian American Film and Video

Identities in Motion: Asian American Film and Video By Peter X. Feng Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-82232-983-2. 44 illustrations, 304 pp. £16.95 Kung Fu Cult Masters: From Bruce Lee to Crouching Dragon By Leon Hunt & The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema By Kyung Hyun Kim & In the Realm of the Senses By Joan Mellen Kung Fu Cult Masters: From Bruce Lee to Crouching Dragon By Leon Hunt London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2003. ISBN 1-90336-463-9. 12 illustrations, 224pp. £15.99 The Remasculinization of Korean Cinema By Kyung Hyun Kim Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-82233-267-1. 66 illustrations, 368pp. £10.80 In the Realm of the Senses By Joan Mellen London: BFI, 2004. ISBN: 1 84457 034 7. 69 illustrations, 87pp. £8.99 A review by Brian Curtin, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand In 1995 the cultural critic and novelist Lawrence Chua wrote "The canon of Asian Pacific American filmmaking in this country is a library of victimization and self-deprecation". Writing of "dewy-eyed invocation of racial community", "the innocent construction of an essential Asian subject" and, with the example of Ang Lee's The Wedding Banquet (1993), the family and the nation as purportedly the only redemptive models of resistance being articulated, he provided a particularly savage indictment of how 'Asians' in the US represent and are represented ('The Postmodern Ethnic Brunch: Devouring Difference', Nayland Blake, Lawrence Rinder and Amy Scholder (eds.), In A Different Light: Visual Culture, Sexual Identity, Queer Practice, City Lights Books, 1995: 62). -

Le Cinéma De Léos Carax Jean-François Hamel

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:58 Ciné-Bulles L’image est bonheur Le cinéma de Léos Carax Jean-François Hamel Volume 30, numéro 4, automne 2012 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/67495ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (imprimé) 1923-3221 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Hamel, J.-F. (2012). L’image est bonheur : le cinéma de Léos Carax. Ciné-Bulles, 30(4), 18–23. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2012 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Le cinéma de Léos Carax VE PERSPECTI L’image est bonheur JEAN-FRANÇOIS HAMEL 18 Volume 30 numéro 4 Léos Carax sur le tournage de Holy Motors Léos Carax. Pour les uns, ce nom est inconnu ou encore d’une renaissance d’outre-tombe, qui extirperait l’artiste de son obscur. Plusieurs n’ont pas vu ses films ou en ont simplement sommeil pour le placer au sein de sa nouvelle création. Et à entendu parler; d’autres ont été indignés, perdus par les pro- travers cette apparition se trouverait l’incarnation du specta- positions de ce cinéaste résolument singulier. -

Mise En Page 1

L'Histoire dira qu'avant ou après sa mort il se trouva en présence de Dieu et lui dit : “ Moi qui aie été tant d'hommes en vain, je voudrais n'être qu'un : moi”. La voix du Seigneur lui répondit depuis un tourbillon : “ Moi-même, je ne suis pas un ; j'ai rêvé le monde comme tu as rêvé ton oeuvre, mon Shakespeare, et parmi les figures de mon rêve tu te trouvais, toi qui es comme moi, plusieurs et aucun.” Jorge Luis Borges — “Everything and Nothing” PreSSe mArTine mArignAc, mAurice TincHAnT AnDré-PAuL ricci / Tony Arnoux et ALberT PreVoST 6, Place de la Madeleine - 75008 Paris présentent Tél. : 01 49 53 04 20 • [email protected] à Cannes : André-Paul ricci : 0612 44 30 62 Tony Arnoux : 06 80 10 41 03 DiSTribuTion LeS FiLmS Du LoSAnge 22, avenue Pierre 1er de serbie - 75116 Paris Tél. : 01 44 43 87 15 / 16 / 17 www.lesfilmsdulosange.fr à Cannes : résidence du gray d'Albion - 64 ter rue d'Antibes entrée 3A / 4ème étage / Appartement n°441 - 06400 Cannes Tél. : 04 93 68 44 46 inTernATionAL SALeS WiLD buncH Cannes office : 4, La Croisette – 1st floor (In front of the Palais) - 06400 Cannes Phone : +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 46 Fax : +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 45 carole baraton : [email protected] gary Farkas : [email protected] Vincent maraval : [email protected] gael nouaille : [email protected] Silvia Simonutti : [email protected] www.wildbunch.biz inTernATionAL PreSS THe Pr conTAcT Cannes office : All suites garden studio, Park & suites Prestige Cannes Croisette, 12 rue Latour Maubourg - 06400 Cannes email: [email protected] Phil symes : +33 (0) 6 29 87 62 96 ronaldo Mourao : +33 (0) 6 29 84 74 07 un FiLm De Photos & dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.filmsdulosange.fr LeoS cArAx le 4 juillet au cinéma France • couleur • 1h55 • DcP • Dolby SrD SynoPSiS De l'aube à la nuit, quelques heures dans l'existence de Monsieur oscar, un être qui voyage de vie en vie. -

Leos Carax Denis Lavant, Eva Mendes, Kylie Minogue

Persmap France • Colour • 1h50 • DCP • Dolby SRD - Herengracht 328 III - 1016 CE Amsterdam - T: 020 5308848- F: 020 5308849 - email: [email protected] Holy Motors Een film van Leos Carax Denis Lavant, Eva Mendes, Kylie Minogue Holy Motors volgt één dag uit het leven van Monsieur Oscar. Hij reist van zonsopgang tot na middernacht van het ene naar het andere leven. Zijn enige metgezel, de slanke blonde Céline, rijdt hem in een limousine door de straten van Parijs. Monsieur Oscar stapt de wereld in, in vele gedaanten als bijvoorbeeld rijke zakenman, moordenaar, bedelaar, gek of familieman. Steeds duikt hij als een volleerd acteur in een nieuwe rol, maar waar zijn de camera’s? Voor een mysterieuze drijvende kracht werkt Monsieur Oscar heel precies van doel naar doel en streeft naar de beste uitvoering van zijn daden. Speelduur: 110 min. – Land: Frankrijk – Jaar: 2012 - Genre: Drama Releasedatum: 9 augustus 2012 Distributie: Cinéart Meer informatie: Publiciteit & Marketing: Cinéart Janneke De Jong Herengracht 328 III 1016 CE Amsterdam Tel: +31 (0)20 5308840 Email: [email protected] Persmap en foto’s staan op: www.cineart.nl Persrubriek: inlog: cineart / wachtwoord: film - Herengracht 328 III - 1016 CE Amsterdam - T: 020 5308848- F: 020 5308849 - email: [email protected] CAST Monsieur Oscar / Banker / Beggar woman/ Denis Lavant Motion capture specialist / Monsieur Merde / The father / The accordionist / The killer / The victim / The dying man / The man in the house Céline Édith Scob Eva / Jean Kylie Minogue Kay M. Eva Mendes Angèle Jeanne Disson -

DP Tokyo Inter V2 9/05/08 18:12 Page 2

DP TokyoInterV29/05/0818:12Page12 Design : Benjamin Seznec / TROÏKA DP Tokyo Inter V2 9/05/08 18:12 Page 2 comme des cinémas PRESENTS A FILM BY MICHEL GONDRY LEOS CARAX BONG JOON-HO INTERNATIONAL PRESS INTERNATIONAL SALES PR CONTACT WILD BUNCH CANNES OFFICE: VINCENT MARAVAL All Suites Garden Studio, cell +33 6 11 91 23 93 All Suites Residence, [email protected] 12 rue Latour Maubourg 06400 Cannes GAEL NOUAILLE [email protected] cell +33 6 21 23 04 72 FRANCE / JAPAN / KOREA / GERMANY [email protected] COLOUR - 1H50 - 35 MM -1.85 Effective only from May 13: DOLBY SRD / DTS - 2008 Phil Symes 06 16 78 85 17 LAURENT BAUDENS / CAROLE BARATON Ronaldo Mourao 06 16 02 80 85 cell +33 6 70 79 05 17 Virginia Garcia 06 34 27 85 51 [email protected] Emmanuelle Boudier 06 34 28 85 21 high definition pictures Stella Wilson 06 34 29 84 87 can be downloaded from SILVIA SIMONUTTI www.wildbunch.biz cell +33 6 20 74 95 08 in the press section [email protected] DP Tokyo Inter V2 9/05/08 18:12 Page 4 INTERIORa film by Michel GONDRY DESIGN A young couple tries to set themselves up in Tokyo. The young man’s ambition is clear – to become a film director. His girlfriend, far more indecisive, cannot escape the vague feeling that she’s losing control of her life. Directionless, both are beginning to go under in this vast city until the young woman, utterly alone, becomes the object of a bizarre transformation... a film MERDEby Leos CARAX A mysterious creature spreads panic in the streets of Tokyo by means of his provocative and destructive behaviour. -

Leos Carax Regis Dialogue with Kent Jones, 2000

Leos Carax Regis Dialogue with Kent Jones, 2000 Kent Jones: I’m here at the Walker Art Center for a Regis Dialogue with Leos Carax, the acclaimed French director whose work includes Boy Meets Girl, Mauvais Sang or Bad Blood, Lovers on the Bridge and Pola X, his new film. Kent Jones: My name is Kent Jones, I'm the Associate Director of Programming at the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York and a film critic, and I'll be talking with Leos about his work tonight. So please join us for this Regis Dialogue. Kent Jones: Hi Leos. I guess that the best place to start is to just talk a little bit about Sans Titre and well, how you came to make the choices that you did for the film, to assemble those particular clips. Leos Carax: I was supposed to shoot my last film, Pola X, and we didn't have the money. So we had to wait. In the meanwhile the Cannes Festival proposed that. And I thought it could be a way to get money to start the film. So we shot two sequences that would be included in the film that we started to shoot that summer, a few months after Cannes Festival. Leos Carax: It was improvised short, since it had to be addressed to the Festival, and I started with the steps. And that brought me to this image, one of my favorite film is The Crowd by King Vidor. And this image of this child going up the stairs and finding out he lost his.. -

Fcnl Newsletter

FCNL NEWSLETTER http://fcnl.frenchculture.org/sent/show/62ce5ac2895f953d3889a612da4004d2 Can't see images? Click here to view this message in a browser JANUARY 31, 2013 IN THIS ISSUE SPECIAL ANNOUCEMENTS LECTURES CONCERTS EXHIBITIONS CINEMA STILL HAPPENING Join Boston in French! Boston in French is an exciting website where you can connect with others who Overdrive: The Films of Léos Carax, love the French language and culture. Join today, with the Filmmaker in Person create a profile and share your love of French culture, Feb 15 – 24, 2013 art, movies, theatre and Harvard Film Archive especially the French 24 Quincy St., Cambridge language with others in the New England area! The Harvard Film Archive is pleased to present Overdrive: The Films of Léos Join today! Carax , with an appearance by the filmmaker himself ( Sunday, February 24 at 7pm ). One of the most talented film directors of his time, Leos Carax is noted for his poetic style and his tortured depictions of love. This retrospective will present his first major work Boy Meets Girl (1984), the famous Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (The Lovers on the Bridge - 1991), the controversial Pola X (1999), Tokyo! (2008), Mauvais sang (Bad Blood - 1986) and Holy Motors (2012), which has emerged as one of last year’s most lauded films. READ MORE 1 sur 9 31/01/2013 14:47 FCNL NEWSLETTER http://fcnl.frenchculture.org/sent/show/62ce5ac2895f953d3889a612da4004d2 Providence French Film Festival 2013 Feb 21- March 3, 2013 Cable Car Cinema 204 South Main St.,Providence, RI Since 1996, the Providence French Film Festival has featured a dazzling display of French movies to francophiles across New England. -

W Kinach Od 20 Sierpnia ANNETTE W Kinach Od 20 Sierpnia

ANNETTE w kinach od 20 sierpnia OPIS FILMU „Annette” to historia miłości słynnego komika Henry’ego Marion Cotillard („Niczego nie żałuję - Edith Piaf”) oraz nominowanego do i Ann, śpiewaczki o międzynarodowej sławie. W świetle reflektorów stanowią Oscara Adama Drivera („Historia małżeńska”, saga „Gwiezdne Wojny”). Muzykę idealną, szczęśliwą parę. Ich życie odmienią narodziny pierwszego dziecka, i piosenki do filmu skomponował zespół Sparks. Annette, dziewczynki o wyjątkowym darze. „Annette” to porywający, widowiskowy spektakl, który kipi od emocji. Nowy film mistrza światowego kina Leosa Caraxa („Holy Motors”) to Film miał swoją światową premierę na tegorocznym Międzynarodowym Festiwalu ponadczasowa opowieść o miłości, zazdrości i zemście. Do swojej pierwszej Filmowym w Cannes jako tytuł otwierający francuską imprezę. Leos Carax anglojęzycznej produkcji francuski twórca zaangażował zdobywczynię Oscara wyjechał z Cannes z Nagrodą za Najlepszą Reżyserię. ANNETTE w kinach od 20 sierpnia DLACZEGO WARTO OBEJRZEC´ TEN FILM? Film otwierał tegoroczny Międzynarodowy 3 Festiwal Filmowy w Cannes. Leos Carax został uhonorowany na festiwalu Nagrodą za Najlepszą Reżyserię. Jedna z najdroższych i najbardziej 4 spektakularnych europejskich produkcji ostatnich lat. Scenariusz, piosenki i muzykę do filmu stworzył 5 legendarny amerykański zespół Sparks. W obsadzie gwiazdy światowego kina Za produkcję muzyczną filmu odpowiadają 1 – Adam Driver i Marion Cotillard. 6 twórcy „La La Land” i „Moulin Rouge!”. Pierwszy anglojęzyczny film wizjonera kina 2 Leosa Caraxa, poetyckiego geniusza i „l’enfant Film zebrał entuzjastyczne recenzje w Cannes terrible” francuskiego kina, twórcy wielokrotnie 7 i aż 89% na Rotten Tomatoes, jednocześnie nagradzanego „Holy Motors”. dzieląc zarówno widzów, jak i krytyków. ANNETTE w kinach od 20 sierpnia TWÓRCY LEOS CARAX Urodzony w 1960 roku reżyser, do Nagrody BAFTA dla Najlepszego Filmu scenarzysta i krytyk filmowy, „l’enfant Zagranicznego, zdobył również trzy Europejskie terrible” francuskiego kina. -

14172D8b67ba0ee4fb53963b0b

History adds that before or after dying he found himself in the presence of God and told Him: “I who have been so many men in vain want to be one and myself.” The voice of the Lord answered from a whirlwind: “Neither am I anyone; I have dreamt the world as you dreamt your work, my Shakespeare, and among the forms in my dream are you, who like myself are many and no one.” JORGE LUIS BORGES - “Everything and Nothing” MARTINE MARIGNAC, MAURICE TINCHANT and ALBERT PREVOST present INTERNATIONAL SALES: Cannes office: 4, La Croisette - 1st floor (In front of the Palais) - 06400 Cannes Phone: +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 46 Fax: +33 (0) 4 93 30 17 45 Carole BARATON: [email protected] Gary FARKAS: [email protected] Vincent MARAVAL: [email protected] Gael NOUAILLE: [email protected] Silvia SIMONUTTI: [email protected] www.wildbunch.biz INTERNATIONAL PR: THE PR CONTACT Cannes office: All Suites Garden Studio, Park & Suites Prestige Cannes Croisette, 12 rue Latour Maubourg - 06400 Cannes Email: [email protected] A FILM BY Phil SYMES: +33 (0) 6 29 87 62 96 Ronaldo MOURAO: +33 (0) 6 29 84 74 07 LEOS CARAX France • colour • 1h55 • DcP • Dolby SrD SynoPSiS From dawn to after nightfall, a few hours in the life of Monsieur Oscar, a shadowy character who journeys from one life to the next. He is, in turn, captain of industry, assassin, beggar, monster, family man... He seems to be playing roles, plunging headlong into each part... but where are the cameras? Monsieur Oscar is alone, accompanied only by Céline, the slender blonde woman behind the wheel of the vast engine that transports him in and around Paris.