Mingo, Pilot Knob and Ozark Cavefish National Wildlve Refuges Comprehensive Conservation Plan Approval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6439/docket-no-fws-hq-nwrs-2019-0040-fxrs12610900000-190-ff09r20000-6439.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 09/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-18054, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333-15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Parts 26, 32, 36, and 71 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–NWRS–2019–0040; FXRS12610900000-190-FF09R20000] RIN 1018-BD79 2019–2020 Station-Specific Hunting and Sport Fishing Regulations AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), open seven National Wildlife Refuges (NWRs) that are currently closed to hunting and sport fishing. In addition, we expand hunting and sport fishing at 70 other NWRs, and add pertinent station-specific regulations for other NWRs that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing for the 2019–2020 season. We also formally open 15 units of the National Fish Hatchery System to hunting and sport fishing. We also add pertinent station- specific regulations that pertain to migratory game bird hunting, upland game hunting, big game hunting, and sport fishing at these 15 National Fish Hatcheries (NFHs) for the 2019–2020 season. This rule includes global administrative updates to every NWR entry in our refuge- specific regulations and the reorganization of general public use regulations. We remove approximately 2,100 regulations that will have no impact on the administration of hunting and sport fishing within the National Wildlife Refuge System. We also simplify over 2,900 refuge- specific regulations to comply with a Presidential mandate to adhere to plain language standards 1 and to reduce the regulatory burden on the public. -

50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–15 Edition) § 32.44

§ 32.44 50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–15 Edition) 4. Deer check station dates, locations, and the field, including shot shells used for hunt- requirements are designated in the refuge ing wild turkey (see § 32.2(k)). brochure. Prior to leaving the refuge, you B. Upland Game Hunting. We allow upland must check all harvested deer at the nearest game hunting on designated areas of the ref- self-service check station following the post- uge in accordance with State regulations ed instructions. subject to the following conditions: 5. Hunters may possess and hunt from only 1. Condition A3 applies. one stand or blind. Hunters may place a deer 2. We allow upland game hunting on the stand or blind 48 hours prior to a hunt and 131-acre mainland unit of Boone’s Crossing must remove it within 48 hours after each with archery methods only. On Johnson Is- designated hunt with the exception of closed land, we allow hunting of game animals dur- areas where special regulations apply (see ing Statewide seasons using archery methods brochure). or shotguns using shot no larger than BB. 6. During designated muzzleloader hunts, C. Big Game Hunting. We allow hunting of we allow archery equipment and deer and turkey on designated areas of the muzzleloaders loaded with a single ball; we refuge in accordance with State regulations prohibit breech-loading firearms of any type. subject to the following conditions: 7. Limited draw hunts require a Limited 1. We prohibit the construction or use of Hunt Permit (name/address/phone number) permanent blinds, platforms, or ladders at assigned by random computer drawing. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

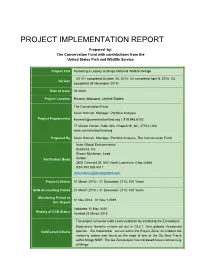

Project Implementation Report

PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION REPORT Prepared by: The Conservation Fund with contributions from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service Project Title Restoring a Legacy at Mingo National Wildlife Refuge V3 (V1 completed October 30, 2014; V2 completed April 8, 2015; V3 Version completed 26 November 2019) Date of Issue 03 2020 Project Location Puxico, Missouri, United States The Conservation Fund Kevin Harnish, Manager, Portfolio Analysis Project Proponent(s) [email protected] | 919.948.6152 77 Vilcom Center, Suite 340, Chapel Hill, NC, 27514 USA www.conservationfund.org Prepared By Kevin Harnish, Manager, Portfolio Analysis, The Conservation Fund Aster Global Environmental Solutions, Inc. Shawn McMahon, Lead Verification Body Verifier 3800 Clermont St. NW, North Lawrence, Ohio 44666 USA 904.626.6011 [email protected] Project Lifetime 01 March 2010 – 31 December 2110; 100 Years GHG Accounting Period 01 March 2010 – 31 December 2110; 100 Years Monitoring Period of 01 Nov 2014– 01 Nov 1 2019 this Report Validated 12 May 2010 History of CCB Status Verified 23 March 2015 The project achieved Gold Level validation by satisfying the Exceptional Biodiversity Benefits criteria set out in GL3.1. One globally threatened Gold Level Criteria species – the Indiana bat –occurs within the Project Zone. An Indiana bat maternity colony was found on the edge of one of the Go Zero Tracts within Mingo NWR. The Go Zero project has increased forest connectivity at Mingo NWR and improved and expanded Indiana bat habitat by increasing the amount of continuous vegetation in riparian zones. Table of Contents The page numbers of the table of contents below shall be updated upon completion of the report. -

TAUM SAUK AREA THREATENED by HYDRO PLANT by Susan Flader

(This article was first published in Heritage, the Newsletter of the Missouri Parks Association, August 2001) TAUM SAUK AREA THREATENED BY HYDRO PLANT by Susan Flader When state park officials selected a cover photo to illustrate their first-ever assessment of "threats to the parks" nearly a decade ago, they chose not a scene of despoliation but a symbolic representation of the best of what they were seeking to protect. It was a vista at the core of the Ozarks, looking from the state's grandest waterfall near its tallest peak across its deepest valley into the heart of Taum Sauk Mountain State Park, Missouri's then-newest public park but also its geologically oldest, wildest, most intact, and most ecologically diverse landscape. Scarcely could one imagine that the very symbol of what they were seeking to protect through their threats study, titled "Challenge of the '90s," would itself become the most seriously threatened landscape in Missouri at the dawn of the new millennium. The photo showed two forest-blanketed, time-gentled igneous knobs in the heart of the St. Francois Mountains, on the left Smoke Hill, recently acquired by the state, and on the right Church Mountain, leased to the Department of Natural Resources for park trail development by Union Electric Company of St. Louis (now AmerenUE). But on June 8, the Ameren Development Company, a subsidiary of Ameren Corporation, filed an application for a preliminary permit with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for the Church Mountain Pumped Storage Project. It would consist of a 130-acre reservoir ringed by a 12,350-foot-long, 90-foot-high dam on the top of Church Mountain, a lower reservoir of 400 acres formed by a 1,900-foot-long, 100-foot high dam flooding several miles of Taum Sauk Creek, which has been designated a State Outstanding Resource Water, and associated tunnels, powerhouse, transmission lines, roads, and related facilities. -

Pilot Knob, Missouri Civil War Telegram Collection (R0137)

Pilot Knob, Missouri Civil War Telegram Collection (R0137) Collection Number: R0137 Collection Title: Pilot Knob, Missouri Civil War Telegram Collection Dates: 1862-1863 Creator: Iron County Historical Society Abstract: The Pilot Knob, Missouri Civil War Telegram Collection contains photocopies of telegrams sent and received by Colonel John B. Gray, commander of the Union post at Pilot Knob, Iron County, Missouri. The dispatches include communications with district headquarters at Saint Louis, and with detachments throughout southeastern Missouri, especially those at Fredericktown, Patterson, Van Buren, and Barnesville. The telegrams cover the period from November 1862 to April 1863. Collection Size: 0.02 cubic foot (2 folders) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Rolla. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: Materials in this collection may be protected by copyrights and other rights. See Rights & Reproductions on the Society’s website for more information about reproductions and permission to publish. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Pilot Knob, Missouri Civil War Telegram Collection (R0137); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Rolla [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Rolla]. Donor Information: The collection was loaned for photocopying to the University of Missouri by the Iron County Historical Society on December 10, 1982 (Accession No. RA0155). Custodial History: Mrs. Pollie Hollie, the archivist and historian of the Immanuel Lutheran Church, where the telegrams were found, located the Pilot Knob telegrams. -

Discover Southeast Missouri

park’s paved trail which is produced nearly 80% of the nation’s mined lead. St. Joe When was the last time you waded Cape Girardeau County handicap accessible and signed Perry County State Park, Missouri’s second largest state park, is located in the heart of barefoot in a mountain stream, fell in SLIP ON SOME WALKING SHOES and grab the camera be- in Braille. Granite quarried at this EXPECT THE UNUSUAL among the gently rolling hills of Perry the old Lead Belt. The park offers picnicking, camping, hiking, mountain bik- with a singing group of French revelers, cause there’s a lot to see and do in Cape Girardeau, the largest city in site was used to pave the streets of the St. Louis riverfront and the County. In Perryville, the County seat, explore the grounds of the St. ing, four fishing lakes and two swimming beaches. The park is equipped for felt the “rush” of a ride down a water Southeast Missouri. In old downtown Cape, sip a coffee at an outdoor café abandoned granite quarry is its own monument to a glorious past. Mary of the Barrens Seminary, the first college west of the Mississippi. equestrian camping and has a campground for visitors with off-road vehicles. slide or sat quietly enjoying the beauty of in the shadow of the 1854 Court of Common Pleas, browse through a Located within this historic district are the National Shrine of the nature? If none of this sounds familiar, maybe variety of shops and boutiques or stroll through Riverfront Park for a great In Pilot Knob, a visit to the Fort Davidson State Historic Site is a must. -

Directory of Missouri Historical Records Repositories

MISSOURI SECRETARY OF STATE JOHN R. ASHCROFT Directory of Missouri Historical Records Repositories Organization Name: Adair County Historical Society Street Address: 211 South Elson City, State, Zip Code: Kirksville, MO 63501 County: Adair Phone: 660-665-6502 Fax: Website: adairchs.org Email: [email protected] Hours of Operation: Wed, Thurs, Fri 1 PM-4 PM Focus Area: Genealogy and Local History Collection Policy: Subject Areas Supported by Institution Civil War/Border War Genealogy Organization Name: Adair County Public Library Street Address: One Library Ln City, State, Zip Code: Kirksville, MO 63501 County: Adair Phone: 660-665-6038 Fax: 660-627-0028 Website: youseemore.com/adairpl Email: [email protected] Hours of Operation: Tues-Wed 9 AM-8 PM, Thurs-Fri 9 AM-6 PM, Sat Noon-4 PM Focus Area: Porter School Photographs, Marie Turner Harvey - Pioneer Educator in Porter School, Adair County Collection Policy: Subject Areas Supported by Institution Education Organization Name: Albany Carnegie Public Library Street Address: 101 West Clay City, State, Zip Code: Albany, MO 64402 County: Gentry Phone: 660-726-5615 Fax: Website: carnegie.lib.mo.us Email: [email protected] Hours of Operation: Mon, Wed 11 AM-7 PM; Tues, Thurs, Fri 11 AM-5 PM; Sat 9 AM-Noon Focus Area: We have a collection of minutes, programs and photographs of local women's social clubs, lodges, library history, local scrapbooks. Collection Policy: Subject Areas Supported by Institution Local History Oral History Women Tuesday, July 23, 2019 Page 1 of 115 Organization Name: Alexander Majors Historical Foundation Street Address: 8201 State Line Rd City, State, Zip Code: Kansas City, MO, 64114 County: Jackson Phone: 816-333-5556 Fax: 816-361-0635 Website: Email: Hours of Operation: Apr-Dec Sat-Sun 1 PM-4 PM Focus Area: Collection Policy: Subject Areas Supported by Institution Education Organization Name: American Institute of Architects St. -

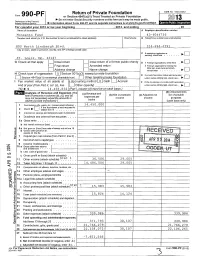

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF Or Section 4947 ( A)(1) Trust Treated As Private Foundation This Form Be Made Public

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation this form be made public. 2013 ► Do not enter Social Security numbers on as it may Revenuethe Treasury InternalInte Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www. irs. gov/form990(^ f. For calendar y ear 2013 or tax y ear be g innin g , 2013 , and endin g 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number Mon.Gantn Fund 43-6044736 Number and street (or P 0 box number tf mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 800 North Lindber g h Blvd. 314-694-4391 City or town, state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is ► pending , check here • • • • • • St. Louis, Mo. 63167 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address chang e Name chang e computation ► H Check type of organization X Section 501(c 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 (a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507 (b)(1)(A), check here . ► I Fair market value of all assets at J Accountin g method X Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination under section 507(b )(1)(B), check here end of year (from Part ll, col (c), line Other ( specify) . -

Refuge Update – November/December 2007, Volume 4, Number 6

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln RefugeUpdate (USFWS-NWRS) US Fish & Wildlife Service 11-2007 Refuge Update – November/December 2007, Volume 4, Number 6 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/refugeupdate Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons "Refuge Update – November/December 2007, Volume 4, Number 6" (2007). RefugeUpdate (USFWS- NWRS). 36. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/refugeupdate/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Fish & Wildlife Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in RefugeUpdate (USFWS- NWRS) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System Inside RefugeUpdate November/December 2007 Vol 4, No 6 Celebrating 20 Years of Science on the M/ V Tiglax, page 5 Kevin Bell is honored as Captain National Wildlife Refuges Return Economic of the largest ship operated by the National Wildlife Refuge System. Benefit Along with Wildlife Values Focus on…A River Runs Through It, pages 8-15 Rivers on refuges are managed for recreation, habitat restoration, water rights and sheer beauty. The Fight Against Giant Salvinia, page 18 Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge in Texas is fighting a weed that can travel three-quarters of a mile in 24 hours. Awards, page 21 From protecting the land to going “green,” awards recognize excellence. Ten New Refuge Friends Groups: • Columbia Gorge Refuge Stewards (Washington) • Friends of Deer Flat National The Refuge System generated almost $1.7 billion in economic return for regional economies in 2006, Wildlife Refuge (Idaho) including money spent on wildlife observation, birding and photography. -

Appendix G - Roadless Area/Wilderness Evaluations and Wild and Scenic Rivers

Appendix G - Roadless Area/Wilderness Evaluations and Wild and Scenic Rivers In accordance with 36 CFR 219.17, a new inventory of roadless areas was completed for this plan revision, and areas of the Ouachita National Forest that met the criteria for inclusion in the roadless area inventory (Chapter 7 of Forest Service Handbook 1909.12) were further evaluated for recommendation as potential wilderness areas. The reinventory of roadless areas included previously recognized roadless areas considered during development of the 1986 Forest Plan and the 1990 Amended Forest Plan. These areas were: Beech Creek, Rich Mountain, Blue Mountain, Brush Heap, Bear Mountain, and Little Blakely. Also, two areas near Broken Bow Lake in Southeastern Oklahoma, Bee Mountain and Ashford Peak, were identified in the January 2002 FEIS for Acquired Lands in Southeastern Oklahoma. Possible additions to existing wilderness areas were also considered. The roadless inventory for the Ouachita National Forest was updated for this iteration of plan revision using Geographic Information System (GIS) technology. Evaluation of the Forest for areas meeting the criterion of one-half mile of improved [National Forest System] road or less per 1,000 acres yielded a significant number of candidate polygons and all polygons over 1,000 acres in size were considered to determine if there were any possibility of expanding the area to a suitable size to warrant consideration as possible wilderness. Polygons meeting the initial criteria were further analyzed using criteria found in FSH 1909.12 (Chapter 7.11) to produce the inventoried roadless areas described in this appendix. The planning team determined that, of the former RARE II areas, the only ones that meet the criteria for inclusion in the roadless area inventory are portions of Blue Mountain and Brush Heap. -

SE States DRMP EIS VOL2.Pdf

Mission Statement It is the mission of the Bureau of Land Management to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. BLM/ES/PL-14/001+1610 Cover Photos: Background – Meadowood Special Recreation Management Area, Fairfax County, Virginia. Foreground from top to bottom – Tidal Lagoon Overlook, Great Egret, Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Outstanding Natural Area, Palm Beach County, Florida; Phosphate Operations, Polk County, Florida; Big Saline Bayou Special Recreation Management Area, Rapides Parish, Louisiana. Southeastern States DRAFT RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Volume 2 of 3 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Southeastern States Field Office September 2014 This page intentionally left blank Draft EIS Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1—PURPOSE AND NEED CHAPTER 2—ALTERNATIVES CHAPTER 3—AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT VOLUME 2 CHAPTER 4—ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES CHAPTER 5—CONSULTATION AND COORDINATION CHAPTER 6—LIST OF PREPARERS GLOSSARY ACRONYMS REFERENCES VOLUME 3 APPENDICES Southeastern States RMP i Table of Contents Draft EIS VOLUME 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 4 —ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES .......................................................................................4-1 4.1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4-1 4.1.1 Approach to the Analysis