Marcel Breuer Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum

1 Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum (by Hugh Grant, Founding Director and Curator, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art) Kirkland Museum’s decorative art collection contains more than 15,000 objects which have been chosen to demonstrate the major design styles from the later 19th century into the 21st century. About 3,500 design works are on view at any one time and many have been loaned to other organizations. We are recognized as having one of the most important international modernist collections displayed in any North American museum. Many of the designers listed below—but not all—have works in the Kirkland Museum collection. Each design movement is certainly a confirmation of human ingenuity, imagination and a triumph of the positive aspects of the human spirit. Arts & Crafts, International 1860–c. 1918; American 1876–early 1920s Arts & Crafts can be seen as the first modernistic design style to break with Victorian and other fashionable styles of the time, beginning in the 1860s in England and specifically dating to the Red House of 1860 of William Morris (1834–1896). Arts & Crafts is a philosophy as much as a design style or movement, stemming from its application by William Morris and others who were influenced, to one degree or another, by the writings of John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin. In a reaction against the mass production of cheap, badly- designed, machine-made goods, and its demeaning treatment of workers, Morris and others championed hand- made craftsmanship with quality materials done in supportive communes—which were seen as a revival of the medieval guilds and a return to artisan workshops. -

One Or Several Rationalisms

One or Several Rationalisms DAVID RlFKlND Columbia University In the Jvears between the two world wars. Italian archtects. critics (Architettura, Casabella, Quadrante, Dedalo, etc.). Such classification, and historians vigorously debated the proper role and form of however, is misleadmg.The major polemical figures of this period often architecture.The stakes in these debates were hgh -polemicists from found themselves collaborating with the same people whom they had, all camps saw architecture as part of a broader project of cultural renewal or would later, criticize strongly. A prime example is Pagano's and tied to the political program of fascism, and argued that archtecture Piacentini's work together at the City University and E'42 .Though the must represent the goals and values of the fascist regime. As such, they former's functionalist modernism and the latter's stylized neoclassicism addressed the issues of modernization, technology, functionalism and seem incomoatible.I both architects shared an exoressedI interest in structural expression raised by international modernism alongside developing an appropriate architectural expression of Italianitri. soecificallv Italian concerns. such as the tradition of classicism and i Eventually, however, Pagano would join the attack on Piacentini's architecture's relationship to the urban fabric. persistent use of classical ornament .2 Ths paper is part of my ongoing dssertation research into the role To some degree the level of collaboration in interwar Italv was also 0 J of the magazine Quadrante, one of the key vehicles of interwar Italian the result of a pragmatism among its architects, who were practitioners architectural discourse, and its relationship to other journals, such as as well as theorists, and thus found compromise a neccesary step toward Casabella. -

The Road to Swiss International Design the Road to Swiss International Design

The Road to Swiss International Design The Road to Swiss International Design Examples of Victorian Advertising The Road to Swiss International Design Swiss International Style was in the “works” for a long time. A variety of historic events factored into the development of this international style, they are: Futurism, De Stijl, Constructivism, The Bauhaus, The School of Design Basel Futurism In 1909, Italian writer, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded Futurism with the publication of his Manifesto of Futurism. The Futurist Manifesto was read and debated all across Europe. Futurism as a revolutionary movement in which all the arts were to text their ideas and forms against the new realities of scientific and indus- trial society. The manifesto voiced enthusiasm for war, the machine age, speed, and modern life. Marinetti and his follows produced an explosive and emotionally charged poetry that defied correct syntax and grammar. Right: Sound Poem by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti The Road to Swiss International Design Suprematism 1915 The term implied the su- premacy of this new art in relation to the past. Malevich saw it as purely aesthetic and concerned only with form, free from any political or social meaning. He stressed the purity of shape, particularly of the square, and he regarded Suprematism as primar- ily an exploration of visual language comparable to contemporary developments in writing. KazmirI Malevich The Road to Swiss International Design Suprematist painting comprised abstract coloured shapes set against light grounds in order to convey feel- ings of ascending, floating, and falling, a visual vocabulary that was subsequently ap- plied to theatre settings and costumes, ceramics, street propaganda, and architecture. -

Art & Architecture Design Cultural Studies

ART & ARCHITECTURE DESIGN CULTURAL STUDIES NEW AND RECENT TITLES THE MIT PRESS Muriel Cooper David Reinfurt and Robert Wiesenberger Foreword by Lisa Strausfeld Afterword by Nicholas Negroponte Muriel Cooper (1925–1994) was the pioneering designer who created the iconic MIT Press colophon (or logo)— seven bars that represent the lowercase letters “mitp” as abstracted books on a shelf. She designed a modernist monument, the encyclopedic volume The Bauhaus (1969), and the graphically dazzling and controversial first edition of Learning from Las Vegas (1972). She used an offset press as an artistic tool, worked with a large-format Polaroid camera, and had an early vision of e-books. Cooper was the first design director of the MIT Press, the cofounder of the Vis- ible Language Workshop at MIT, and the first woman to be granted tenure at MIT’s Media Lab, where she developed software interfaces and taught a new generation of design- ers. She began her four-decade career at MIT by designing vibrant printed flyers for the Office of Publications; her final projects were digital. This lavishly illustrated volume documents Cooper’s career in abundant detail, with prints, sketches, book covers, posters, mechanicals, student projects, and photographs, from her work in design, teaching, and research at MIT. A humanist among scientists, Cooper embraced dynamism, simultaneity, transparency, and expressiveness across all the media she worked in. More than two decades after her career came to a premature end, Muriel Cooper’s legacy is still unfolding. This beautiful slip-cased volume, designed by Yasuyo Iguchi, looks back at a body of work that is as contemporary now as it was when Cooper was experimenting with IBM Selectric typewriters. -

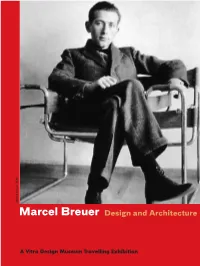

Marcel Breuer Design and Architecture

Marcel Breuer 1928 Breuer Marcel Marcel Breuer Design and Architecture A Vitra Design Museum Travelling Exhibition Considered the “inventor” of tubular steel furniture, the designer and architect Marcel Breuer (1902–1981) is one of the most influential designers of the 20th century. Born and raised in Hungary, he studied at the Bauhaus where he went on to head the furniture workshop from 1925 to 1928. During this period, he produced numerous tubular steel furniture pieces, including the legendary Wassily club chair that brought him international renown. With his furniture in aluminum and molded plywood in the 1930s, he continued to make design history until immigrating to the USA in 1937. First working as a professor at Harvard University, Breuer began a second, highly successful career as an architect. Owing a great deal to modernism, his buildings – primarily single-family homes, university and office buildings as well as museums – were internationally recognized in the 1950s and 1960s for their exemplary character. The retrospective produced by the Vitra Design Museum pays tribute to Breuer’s well-known contributions to 20th century design history. Yet it also brings renewed attention to his architectural works, which have fallen somewhat into oblivion in the past decades. In so doing, it is the first exhibition to give proper attention to both areas of Marcel Breuer’s work. Marcel Breuer Design and Architecture He was an artist. He was the best teacher I ever had. All the others were Bauhaus ideologues. Philip Johnson on Marcel Breuer A Vitra Design Museum Travelling Exhibition 1. Introduction 2. Concept 3. -

Isamu Noguchi and the Creation of a “Universal” Landscape

ABSTRACT Title of Document: ISAMU NOGUCHI AND THE CREATION OF A “UNIVERSAL” LANDSCAPE Rebecca Hanscom Merritt, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Steven Mansbach Department of Art History The creation of landscapes allowed Isamu Noguchi to look beyond sculpture to an environment where stone, architecture, and landscaping met. This enabled him to think about what he wanted to accomplish as an artist, and by the end of his career landscapes became the aesthetic means to reconcile his “divided self.” He was an artist who had obtained commercial and artistic success at an early age, yet he had to deal with the deeply imbedded psychological challenge of his longing to belong. This apparent discrepancy in his life led Noguchi to create landscapes where he could psychologically belong by making them “universal.” In this paper I explore Noguchi’s struggle in defining his cultural identity, and I examine six gardens created by Noguchi, each coming closer to his wish for a “universal” landscape; an enclosed utopia separated from the chaos of the urban world and cultural definitions. ISAMU NOGUCHI AND THE CREATION OF A “UNIVERSAL” LANDSCAPE By Rebecca Hanscom Merritt Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Steven Mansbach, Chair Professor Joshua Shannon Professor Renee Ater © Copyright by Rebecca Hanscom Merritt 2011 Disclaimer The thesis or dissertation document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner's copyright. A complete version of this document, which includes said referenced material, resides in the University of Maryland, College Park's library collection. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9031153 The utilitarian object as appropriate study for art education: An historical and philosophical inquiry grounded in American and British contexts Sproll, Paul Anthony, Ph.D. -

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Living Minnesota

Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Living Minnesota Artists 7/15/1938 8/31/1938 Stanford Fenelle 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Grandma’s Dolls 1/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Parallels in Art 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Trends in Contemporary Painting 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Time-Off 1/4/1940 1/1/1940 Ways to Art: toward an intelligent understanding 1/4/1940 ?/?/1940 Letters, Words and Books 2/28/1940 4/25/1940 Elof Wedin 3/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Frontiers of American Art 3/16/1940 4/16/1940 Artistry in Glass from Dynastic Egypt to the Twentieth Century 3/27/1940 6/2/1940 Syd Fossum 4/9/1940 5/12/1940 Answers to Questions 5/8/1940 7/1/1940 Edwin Holm 5/14/1940 6/18/1940 Josephine Lutz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Exhibition of Student Work 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Käthe Kollwitz 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title Opening date Closing date Paintings by Greek Children 6/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Jewelry from 1940 B.C. to 1940 A.D. 6/27/1940 7/15/1940 Cameron Booth 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 George Constant 7/1/1940 7/30/1940 Robert Brown 7/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Portraits of Indians and their Arts 7/15/1940 8/15/1940 Mac Le Sueur 9/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Paintings and their X-Rays 9/1/1940 10/15/1940 Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh 9/24/1940 10/14/1940 Walter Kuhlman 10/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Marsden Hartley 11/1/1940 11/30/1940 Clara Mairs 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Meet the Artist 11/1/1940 ?/?/1940 Unpopular Art 11/7/1940 12/29/1940 National Art Week 11/25/1940 12/5/1940 Art of the Nation 12/1/1940 12/31/1940 Anne Wright 1/1/1941 ?/?/1941 Walker Art Center Exhibition Chronology Title -

Leseprobe 9783791359045.Pdf

original bauhaus 5 / Contents / Foreword 7 Annemarie Jaeggi and Thomas Köhler / Greetings 9 Klaus Lederer / Greetings 11 Hortensia Völckers and Alexander Farenholtz / Introduction 13 Nina Wiedemeyer Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / ‘Why is the Bauhaus so important?’ 19 Christian Demand Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 1 Revivals 23 Thomas Tode Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 2 Unity in Diversity 31 Annemarie Jaeggi Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 3 Production—Reproduction 41 Alena J. Williams Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 4 Unique Works in Series 51 Pauline Doutreluingne and Uli Aigner Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 5 Becoming Famous 57 Mercedes Valdivieso Chapter 1 / Becoming Icons / Case Study 6 Family Resemblances 65 Magdalena Droste Chapter 2 / Writing History / An Archive for Contemporary Tasks 75 Esther Cleven Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 7 Lecturing—Exhibiting 79 Annemarie Jaeggi Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 7 Lecturing—Exhibiting 85 Ute Famulla Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 8 Yours Modernly 95 Nicole Opel Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 9 Simple 103 Matthias Noell Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 9 Simple 109 Sigurd Larsen Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 10 Missing—Existing 111 Hans-Friedrich Bormann Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 10 Missing—Existing 119 Christine van Haaren Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 11 Dissimilar Twins 125 Helga Lutz Chapter 2 / Writing History / Case Study 11 Dissimilar Twins 133 Anna Henckel-Donnersmarck -

Society of Architectural Historians, Richmond, VA, 17.-21.4.02

Society of Architectural Historians, Richmond, VA, 17.-21.4.02 Victoria M. Young 6. Society of Architectural Historians CFP 2002 April 17-21 2002, Richmond, Virginia Deadline for paper abstracts: 1 September 2001 The Rebirth of Solids: Redefining Mid-Century Modern Architecture In his 1963 lecture, "Matter and Intrinsic Form," Marcel Breuer detailed his observations on the state of contemporary architecture. Architects, he recognized, had broken away from the spare formalism of the International Style and embraced building shapes and materials which set solid elements next to transparency, and a new plasticity next to lineal purity. Breuer heralded this return of vivid contrasts and sculptural three-dimensional architecture as a resounding rebirth of solids. In their quest for diversity of expression, architects of the 1950s and 1960s challenged the underlying principles of early Modernism and developed their own distinctive idiom. Yet modern architecture of this periodovershadowed by the towering legacy of the International Style and the flamboyant gestures of Post Modernism remains subject to public dislike and political disdain born of misinterpretation and misunderstanding. Today, prominent battles to save and re-use buildings from the mid-century, including Edward Durell Stones 1964 Gallery of Modern Art on Columbus Circle in New York City and Richard Neutra s 1961 Gettysburg Cyclorama Building in Pennsylvania, have inspired academics to reexamine this distinct period of design, outlining the broad contours of what is often referred to as Mid-Century Modern. As scholars prepare to celebrate the centenary anniversary of Breuers birth in 2002, we invite papers that use his idea, the rebirth of solids, as a springboard for revisiting modern architecture of the mid-twentieth century. -

Post-War Detached Houses in Berlin and Their Conservation

Post-War Detached Houses in Berlin and their Conservation Thomas Steigenberger, M.A. Thomas Steigenberger studied Hist01y ofArt , Medieval History and Archaeology in Berlin. Focussing 011 the architectural hist01y ofthe 19h and 2(/h centuries, he is presently writing a thesis 011 the architect and craftsman Bruno Paul (1874-1968): Bnmo Paul - Die Berliner Jahre (1907-1932). In Berlin there are at present approximately fifty post-war detached family homes ofoutstanding quality. Ofthese only a few have the status ofprotected monuments. Due to the strong pressure ofground speculation in the Berlin villa areas since German reunification in 1990, many have already been demolished or are highly endangered. The only possibility to protect these detached-houses against unconsidered demolition in the long-term, is by listing them. A revision of the perception and the acceptance of this architectural genre, which has until now hardly been noticed, is therefore an urgent necessity. Post·Wnr Dc111chcd Houses Post-Wnr Dclllched Houses Californian architecture as their model (Fig. 6).6 Fig. I: Mnp oflhc city with its distribuuon of As many of the villas erected before the Second World War are today districts. Dnhlcm, Wnnnsce nnd Nikol11Ssce neither listed buildings nor enjoy protection on the basis of secure tenure, it is ore parts ofZchlcndorf just the family homes of the post-war period which are extremely sought after as construction sites.' Since the beginning ofthe 1990s, a wave ofdensification has struck, which, in spite of the recession, continues undaunted. It is mostly multiple dwellings, so called 'town villas', which are being erected and strewn a thousand-fold and in similar architectural triviality throughout the whole city.