Restructuring the US Military Bases in Germany Scope, Impacts, and Opportunities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N:\02 Bereiche\2.1 Planung\2.1.2 Bus

Montag - Freitag Verkehrsbeschränkungen S F F S S F S S Anmerkungen r RB 5 Fulda Bahnhof ab 5.48 5.48 7.19 9.19 11.19 11.19 12.19 13.19 13.19 14.19 15.19 17.32 r RB 5 Bad Hersfeld Bahnhof an 6.15 6.15 7.47 9.47 11.46 11.46 12.47 13.47 13.47 14.46 15.46 18.00 r RB 5 Kassel Hauptbahnhof ab 5.06 5.06 7.09 9.10 11.10 11.10 12.10 13.10 13.10 14.10 15.10 17.10 380 r RB 5 Bad Hersfeld Bahnhof an 6.08 6.08 8.11 10.08 12.08 12.08 13.08 14.08 14.08 15.08 16.08 18.08 Bad Hersfeld, Bahnhof 5.20 6.40 6.40 8.30 10.30 12.30 12.30 13.20 14.30 14.30 15.20 16.30 18.30 b Breitenstraße 5.23 6.43 6.43 8.33 10.33 12.33 12.33 13.23 14.33 14.33 15.23 16.33 18.33 Hainstraße 5.24 6.44 6.44 8.34 10.34 12.34 12.34 13.24 14.34 14.34 15.24 16.34 18.34 0 Südtor 5.25 6.45 6.45 8.35 10.35 12.35 12.35 13.25 14.35 14.35 15.25 16.35 18.35 Stadthalle 5.26 6.46 6.46 8.36 10.36 12.36 12.36 13.26 14.36 14.36 15.26 16.36 18.36 Seniorenwohnheim 5.27 6.47 6.47 8.37 10.37 12.37 12.37 13.27 14.37 14.37 15.27 16.37 18.37 St-Elisabeth-KKH 5.28 6.48 6.48 8.38 10.38 12.38 12.38 13.28 14.38 14.38 15.28 16.38 18.38 Ziegelei 5.29 6.49 6.49 8.39 10.39 12.39 12.39 13.29 14.39 14.39 15.29 16.39 18.39 Abzw Eichhof 5.30 6.50 6.50 8.40 10.40 12.40 12.40 13.30 14.40 14.40 15.30 16.40 18.40 Bad Hersfeld-Asbach, Friedhofsweg 5.32 6.52 6.52 8.42 10.42 12.42 12.42 13.32 14.42 14.42 15.32 16.42 18.42 Bad Hersfeld-Kohlhausen )5.33 6.54 )6.53 )8.43 )1043 )1243 )1243 13.34 )1443 )1443 15.34 )1643 )1843 Bad Hersfeld-Asbach, Raiffeisenbank 5.35 6.56 6.55 8.45 10.45 12.45 12.45 - 14.45 14.45 - 16.45 18.45 -

Modellregion Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm Das Modellvorhaben

Modellvorhaben Langfristige Sicherung von Versorgung und Mobilität in ländlichen Räumen Modellregion Eifelkreis Bitburg-Prüm Ziele – Vorgehen – Ergebnisse Das Modellvorhaben Mit dem Modellvorhaben leistet das Bundes Zu den Zielgruppen zählen u. a. Jugendliche, ministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur Familien mit Kindern und Senioren. Durch ihre einen Beitrag dazu, gleichwertige Lebensverhält aktive Einbindung können ihre Ideen aufge nisse in ländlichen Räumen zu gewährleisten. nommen und die Akzeptanz und Effizienz von Es soll die 18 Modellregionen dabei unterstützen, künftigen Lösungen gefördert werden. Daseinsvorsorge, Nahversorgung und Mobilität besser zu verknüpfen, um die Lebensqualität in Je nach Ausgangsbedingungen variiert der der Region zu verbessern und wirtschaftliche strategische Ansatz des Modellvorhabens in den Entwicklung zu ermöglichen. einzelnen Regionen. Während ein Konzept zur Bündelung von Standorten der Daseinsvorsorge In dem Modellvorhaben wird besonderer Wert in „Kooperationsräumen“ eher nur mittel- bis darauf gelegt, dass neben Politik, Verwaltung, langfristig umgesetzt werden kann, wird sich Zivilgesellschaft sowie Anbietern von Daseins ein integriertes Mobilitätskonzept auch schon vorsorgedienstleistungen und Nahversorgung in kürzerer Frist auf die vorhandene Verteilung von Beginn an auch die verschiedenen Ziel und der Daseinsvorsorgeeinrichtungen ausrichten Nutzergruppen vor Ort aktiv in die Entwicklung können. In Verbindung mit dem Kooperations und Umsetzung von Standortkonzepten und raumkonzept -

Refugee and Migrant Labor Market Integration in Germany Status Update and Insights June 1 to August 21, 2017

Refugee and Migrant Labor Market Integration in Germany Status Update and Insights June 1 to August 21, 2017 Table of Contents Highlights to Date 1 The Context, Opportunity, and Challenges 2 1. Potential for Global impact from Germany’s success 2 2. Germany is the “Silicon Valley” of Immigration – and it’s exciting! 3 3. National Challenges, played out at the regional and local Level 3 4. The Stuttgart Ausbildungscampus is a promising local model 3 5. Targets, metrics, and incentives not sufficiently focused on job placement 3 6. All of the programs are “succeeding”, but labor market integration is not yet succeeding 4 Summary of Deliverables Status 5 1. Serve Refugees 5 a. Get hands-on in job readiness and career coaching of refugees 5 b. Facilitate job placement of refugees 5 c. Evaluate appropriateness of UpGlo curriculum/program approach to Germany 5 2. Assess Potential Jobseeker Service Partners 6 a. Get to know the Community Foundation Stuttgart better and campus partners 6 b. Meet and observe programs of other potential partners in Stuttgart and beyond 6 c. Partnership conversations with expansion partners 6 3. Progress Conversations with possible Employer Partners 7 4. Assess Viability of UpGlo Platform to meet German market needs 8 a. Demo the platform for JobCenter/Arbeitsagentur (government) staff 8 b. Demo the platform (Online training only) for refugees 8 c. Decide go/no go to customize platform vs build new German one 8 d. If go, formulate list of customizations, based on feedback from demo participants 8 5. Assess and Evaluate Viability of Revenue Plan 9 a. -

Vogelsbergkreis Fulda Bamberg Gießen Würzburg Haßberge Main

Gieß en Bad S alzschl irf Nüstta l Wahns Mehm els Wasun gen Metzels Zella -M ehli s Langewiesen Köni gse e-Rottenbach Schli tz Nüstta l Nüstta l Kal tennordhe im Oepfershau sen Wallbach Kam sdorf Feldatal Sitzendorf Schwarzburg Benshausen Stützerbach Hünfel d Tann (Rhön) Dröb ischa u Saal feld /S aale Buseck Grünberg Unterweid Unterwell enborn Lauterbach (Hessen ) Aschenhausen Walldorf Oberhain Kaul sdo rf Wartenberg Unterkatz Rippershausen Gehren Herschdorf Reiski rchen Kal tenwestheim Kal tensundhei m Oberkatz Utendorf Kühnd orf Schwarza Mücke Stepfe rshausen Schm iedefeld am Rennsteig Döschni tz Unterweiß bach Hohenwarte Suhl Lautertal (Vogelsberg) Friedersdorf Fernwald Gill ersdorf Neustadt am Rennsteig Wildensprin g Rohrbach Wittgendo rf Ulrichstein Hofbie ber Frauenwald Petersberg Mell enbach-Glasbach Großenl üder Oberweid Gießen Saal feld er Höhe Schmalkalden-Meiningen Dillstädt Böhl en Oberweiß bach/T hür. Wa ld Erbenha usen Fulda Mein ingen Rohr Schm eheim Meura VogelsbergkHerb srtein eis Hilders Reichman nsdo rf Laubach Großbreitenbach Meuselba ch-S chwarzmühl e Pohl heim St. K ilian Melp ers Deesb ach Frankenheim /Rh ön Oberstadt Altenfeld Leutenb erg Dipperz Ell ingshausen Marisfeld Rhönblick Grub Nahetal -W aldau Reichman nsdo rf Lich Eichenb erg Cursdorf Probstzel la Bischofrod Schm iedefeld Bel ri eth Schleusegrund Birx Fladung en Oberma ßfeld-Grim me nthal Sül zfeld Katzhütte Grebenhain Künzell Hosen feld Vachdorf Fulda Unterm aßfeld Ahl städt Lichte Lengfel d Mell richstadter F orst Ein hausen Schotten Leutersdorf Ehrenbe rg (Rhön) Henfstädt Poppe nhausen (Wasserkuppe) Ritschenhausen Gräfenthal Willm ars Hause n Neubrunn Them ar Hungen Schleusi ngen Masserberg Goldisthal Pie sau Nord heim v.d. -

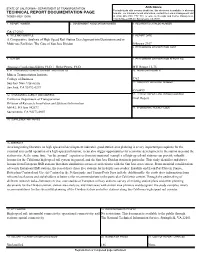

TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Formats

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION ADA Notice For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in alternate TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE formats. For alternate format information, contact the Forms Management Unit TR0003 (REV 10/98) at (916) 445-1233, TTY 711, or write to Records and Forms Management, 1120 N Street, MS-89, Sacramento, CA 95814. 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA-17-2969 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE A Comparative Analysis of High Speed Rail Station Development into Destination and/or Multi-use Facilities: The Case of San Jose Diridon February 2017 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris Ph.D. / Deike Peters, Ph.D. MTI Report 12-75 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER Mineta Transportation Institute College of Business 3762 San José State University 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER San José, CA 95192-0219 65A0499 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Report Division of Research, Innovation and Systems Information MS-42, PO Box 942873 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273-0001 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT As a burgeoning literature on high-speed rail development indicates, good station-area planning is a very important prerequisite for the eventual successful operation of a high-speed rail station; it can also trigger opportunities for economic development in the station area and the station-city. At the same time, “on the ground” experiences from international examples of high-speed rail stations can provide valuable lessons for the California high-speed rail system in general, and the San Jose Diridon station in particular. -

Niederschrift Zur Sitzung Der Lokalen Aktionsgruppe LEADER Des Eifelkreises Bitburg-Prüm Am 15.10.2018

Lokale Aktionsgruppe Bitburg-Prüm Niederschrift zur Sitzung der Lokalen Aktionsgruppe LEADER des Eifelkreises Bitburg-Prüm am 15.10.2018 Sitzungsbeginn: 16.05 Uhr Sitzungsende: 16.55 Uhr Teilnehmer: siehe beigefügte Teilnehmerliste - 25 stimmberechtigte Mitglieder davon: 10 Vertreter öffentlicher Einrichtungen 6 Vertreter der WiSo-Partner 9 Vertreter der Zivilgesellschaft (Vertreter der Arbeitsgemeinschaft bäuerlicher Landwirtschaft ab TOP 3 anwesend) - 3 beratende Mitglieder Anlagen: Anwesenheitsliste; Präsentation Zu TOP 1: Begrüßung, Feststellung der Beschlussfähigkeit sowie der Tagesordnung und Beschlussfassung über die Niederschrift der Sitzung vom 18.04.2018 Der Vorsitzende begrüßte die anwesenden, stimmberechtigten und beratenden LAG- Mitglieder. Es wurden keine Änderungswünsche zur Tagesordnung und zur Niederschrift vom 19.04.2018 vorgebracht. Der Vorsitzende stellte klar, dass die noch nicht in die LAG aufgenommen Mitglieder nicht an der Abstimmung teilnehmen dürfen. Dabei handelte es sich um das neu zu wählende Mitglied des Gemeinde- und Städtebundes – Kreisverband Bitburg-Prüm. Abstimmungsergebnis: Die Beschlussfassung erfolgte einstimmig mit 23 Ja-Stimmen, davon 14 nichtöffentliche Partner [WiSo-Partner (6) und Zivilgesellschaft (8)]. Zu TOP 2: Beschlussfassung zur Zusammensetzung der LAG und Änderung der Geschäftsordnung Die Geschäftsstelle erläuterte, dass aufgrund des Ausscheidens zweier Mitglieder deren Neubesetzung zu beraten sei. Dabei handele es sich um die Vertretung des Seniorenbeirates des Eifelkreises Bitburg-Prüm -

Referenzliste Geotechnik Im Hochbau

IGBW Ingenieurbüro für Geotechnik und Baugrunduntersuchung Wollenhaupt Referenzliste Geotechnik im Hochbau Auszug aus den von der Geschäftsleitung bearbeiteten Projekten (Stand Dezember 2011) IGBW Ingenieurbüro für Geotechnik und Baugrunduntersuchung Wollenhaupt Thüringer Straße 91 36208 Wildeck Telefon 06678 918 0037 – Telefax 06678 918 0009 VR-Bank Bad Hersfeld-Rotenburg (BLZ 532 900 00) Konto Nr. 31191408 Geschäftsführung: Dipl.-Ing. H. Wollenhaupt Geotechnik im Hochbau IGBW - 2 - Jahr Projekt Auftraggeber 2011 Erweiterung Autohaus Salzmann Heike Salzmann Grundbesitzfirma „An der Baugrunduntersuchungen mit Drucksondierungen und Haune“, Bad Hersfeld Kleinbohrungen, chemische Laborversuche, Architekturbüro Dehn, Baugrund- und Gründungsgutachten Bad Hersfeld 2011 Umbau und Erweiterung Weißberghalle, Gemeinde Wildeck Wildeck-Richelsdorf Baugrunduntersuchungen mit Drucksondierungen, Baugrund- und Gründungsgutachten 2011 Neubau Seniorenzentrum, Herz- und Kreislaufzentrum, Herz und Kreislaufzentrum Rotenburg Rotenburg Team Planquadrat, Bebra Neubau eines Gebäudes entlang einer steil abfallenden Böschung Baugrunduntersuchungen, Baugrund- und Gründungsgutachten 2011 Neubau Würth-Halle Schade, Bad Hersfeld Fa. Schade und Sohn, Bad Hersfeld Baugrunduntersuchungen mit Drucksondierungen und Bohrungen, Architekturbüro Rabe, Baugrund- und Gründungsgutachten, fachtechnische Rotenburg Bauüberwachung _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 27-11-2019.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences offers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff, high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major cities www.hs-ansbach.de of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking distance of www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – the old town centre with its historic architecture and landmarks and hs.ansbach its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

A Novel Concept of Screening for Subgrouping Factors for The

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology www.nature.com/jes ARTICLE OPEN A novel concept of screening for subgrouping factors for the association between socioeconomic status and respiratory allergies ✉ Christoph Muysers 1,2 , Fabrizio Messina3, Thomas Keil1,4,5 and Stephanie Roll1 © The Author(s) 2021 BACKGROUND: The new subgroup screening tool “subscreen” aims to understand the unclear and complex association between socioeconomic status (SES) and childhood allergy. This software R package has been successfully used in clinical trials but not in large population-based studies. OBJECTIVE: To screen and identify subgrouping factors explaining their impact on the association between SES and respiratory allergies in childhood and youth. METHODS: Using the national German childhood and youth survey dataset (KiGGS Wave 2), we included 56 suspected subgrouping factors to investigate the association between SES (low vs. high) and allergic rhinitis and/or asthma in an exploratory manner. The package enabled a comprehensive overview of odds ratios when considering the SES impact per subgroup and analogously all disease proportions per subgroup. RESULT: Among the 56 candidate factors, striking subgrouping factors were identified; e.g., if mothers were younger and in the low SES group, their children had a higher risk of asthma. In addition children of the teen’s age were associated with increased risks in the low SES group. For the crude proportions, factors such as (parental) smoking or having had no “contact with farm animals” were identified as strong risk factors for rhinitis. SIGNIFICANCE: The “subscreen” package enabled the detection of notable subgroups for further investigations exemplarily for similar epidemiological research questions. -

Flyer Informationen Zum Studium 08-2020 EN.Indd

Succeed in your studies and enjoy your time in Ansbach Why choose Ansbach? Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Become part of Ansbach University’s vibrant student community! A Residenzstrasse 8 warm welcome awaits you and plenty of support to help you succeed. 91522 Ansbach Germany Ansbach University of Applied Sciences Phone: +49 981 4877 – 0 Ansbach University of Applied Sciences off ers a wide range of study Fax: +49 981 4877 – 188 programmes with a focus on practical training and employability www.hs-ansbach.de/en without tuition fees. Teaching in small groups, close mentoring by dedicated staff , high-tech laboratories, and a green campus in International Offi ce friendly surroundings all combine to make Ansbach University an Bettina Huhn, M.A. (Head) ideal place to study. Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 145 Sandra Sauter Ansbach Phone: +49 981 48 77 – 545 Ansbach is a beautiful town in Bavaria with lots of leisure activities, [email protected] safe surroundings and a low cost of living. Located in the heart of Germany, close to Nuremberg, it allows easy access to the major www.hs-ansbach.de cities of Germany and Europe. The campus lies within walking www.facebook.com/studieren.in.franken Studying in Ansbach – distance of the old town centre with its historic architecture and hs.ansbach landmarks and its multitude of shops and cafés. Information for Services Frankfurt international students Berlin International students receive a wide range of personal support from the International Offi ce. This includes an orientation week Strasbourg . Business – Engineering – Media at the start of semester, German language courses available 2 hours both pre-semester and during the regular semester studies, and Stuttgart. -

Tierärzte Mit Zusatzausbildung Für Augenheilkunde

Tierärzte mit Zusatzausbildung für Augenheilkunde Diese Liste ist eine Aufzählung von Tierärzten, die eine Zusatzausbildung in Augenheilkunde gemacht haben. Sie wurde zusammengestellt mit Hilfe der Informationen des DOK und der Landestierärztekammern. Die Liste ist ein Service des Clubs für Britische Hütehunde. Sie erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit und stellt keine Empfehlung dar. Wir nehmen gerne zusätzliche Adressen auf, wenn uns diese unter Nachweis der Zusatzausbildung beim DOK oder nach den Vorgaben der Weiterbildungsverordnungen der Landestierärztekammern gemeldet werden. Die aktuelle Liste des DOK können Sie unter http://www.dok-vet.de/ finden. CfBrH, Referentin für Zuchtfragen, Vera Bochdalofsky, Hohenfelde 54a, 21720 Mittelnkirchen, Tel.: 04142/81 25 44 Dr. Jörg-Peter Popp (DOK) Diagnostikzentrum für Kleintiere Tierärztliche Klinik Dr. Jörg-Peter Popp Semperstrasse 3c 01069 Dresden [email protected] 03514722898 Dr. Christina Espich Kleintierpraxis Dorfstrasse 36 03096 Briesen [email protected] 035606/4606 Dr. Andrea Steinmetz Universität Leipzig (DOK) An den Tierkliniken 23 04103 Leipzig Tel.: 0341 / 9738700 E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Susanne Voig Tierärztliche Praxis für Augenheilkunde +t Dres. von Krosigk und Voigt Delitzscher Straße 69 04129 Leipzig [email protected] 034191027515 Dr. Ullrich Seidel Tierarztpraxis Windorfer Str. 24 04229 Leipzig Tel.: 0341 / 4249010 Dr. Katrin Penschuck Lausicker Str. 31 A 04299 Leipzig Tel.: 0341- 8775622 Dr. Bettina Rohrbach Arndtstr. 11 04416 Markkleeberg Tel.: 0341 / 3389013 Dr. Gerhard Woitow (DOK) Theodor-Lieser-Str. 11 + 06120 Halle Tel.: 0345/5522513 E-Mail: [email protected] Stand 05./2020 Dr. Manuela Schwede (DOK) Tierärztliche Klinik für Kleintiere u.Pferde Fröbelstr. 25 06886 Lutherstadt Wittenberg Tel.: 03491/663015 Fax: 03491/663016 E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. -

Directions to Campus II (Würzburger Strasse 164, Aschaffenburg)

Directions to Campus I (Würzburger Strasse 45, Aschaffenburg) By public transport: You can reach us via Aschaffenburg main station. From there take the regional train (direction Miltenberg) to the regional train station "Aschaffenburg Hochschule", or take the bus lines 5, 15, 40, 41, 47 or 63 to the stop "Hochschule". By car, coming from "Würzburg": Leave the A3 motorway at the exit "Aschaffenburg Ost" and stay on B26 state road. Turn left into "Stengerstrasse" and drive onto the Südring. After approx. 2 km take the ramp on to "Würzburger Str." and turn left into Würzburger Strasse. To get to the entrance, take "Flachstrasse" following the left-hand bend into the "Bessenbacher Weg". By car, coming from "Frankfurt/M." Leave the A3 at the exit "Aschaffenburg Stockstadt" and take the B8 in the direction of "Mainaschaff". Then take the B26 ramp in the direction of "Darmstadt/Stadtring". Turn onto the "Westring" until you reach "Adenauerbrücke/Westring". Now you are on the "Südring", which you follow until you reach the ramp in the direction of "Haibach/Zentrum/Gailbach" or "Hochschule". From there turn right into Würzburger Strasse. To get to the entrance, take "Flachstrasse" following the left-hand bend into the "Bessenbacher Weg". Directions to Campus II (Würzburger Strasse 164, Aschaffenburg) On foot: From Campus I you walk up Würzburger Strasse for about 12 minutes to get to Campus II. By car: From Campus I, it is a 2 minute drive up Würzburger Strasse to Campus II. By public transport: Take the bus lines 5, 15, 40, 41 and 63 to "Sälzerweg".