Nsw Public Health Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Taree Public School Annual Report

Taree Public School 2019 Annual Report 3167 Page 1 of 16 Taree Public School 3167 (2019) Printed on: 8 April, 2020 Introduction The Annual Report for 2019 is provided to the community of Taree Public School as an account of the school's operations and achievements throughout the year. It provides a detailed account of the progress the school has made to provide high quality educational opportunities for all students, as set out in the school plan. It outlines the findings from self–assessment that reflect the impact of key school strategies for improved learning and the benefit to all students from the expenditure of resources, including equity funding. School contact details Taree Public School Albert St Taree, 2430 www.taree-p.schools.nsw.edu.au [email protected] 6552 1233 Message from the principal I am proud of the achievements of our teachers and students and the progress made towards achieving our school strategic directions. Taree Public School (TPS) delivers high quality teaching learning experiences underpinned by supportive welfare programs and practices. TPS is committed to providing a learning environment that nurtures, guides, inspires and challenges students. We work in partnership with parents and encourage them to be active participants in their child's education. We are proud of the high levels of engagement from our community, evidenced with over 70% of parents and carers attending the Personalised Learning Plan (PLP) BBQ afternoon, along with numerous community events throughout the year. The engagement of members of the school community and partnerships with external agencies support the monitoring of student progress and wellbeing. -

Dooragan National Park Fire Management Strategy

Locality Index Contact Information Dooragan NP Status of Fire Thresholds Vegetation Mid North Coast Region Agency Position / Location Phone Oxley Wild Rivers NP Hat Head NP NPWS Regional Duty Officer 016 301 161 Dooragan National Park Kumbatine NP Maria NP Rainforest Kumbatine SCA Area Manager Hastings 02 6588 5503 Willi Willi NP ! Queens Lake Nature Reserve Fire Management Strategy (Type 2) Crescent Head Wet sclerophyll forest Werrikimbe NP BYABARRA GRANTS HEAD 0417 265 117 2005 Macleay Area 25k mapsheet 25k mapsheet Fire Management Officer 02 6586 8329 Shrubby dry sclerophyll forest 0417497 031 Sheet 1 of 1 94344N 94341N Grassy dry sclerophyll forest Cooperabung Creek NR 02 6584 5894 (fax) This strategy should be used in conjunction with aerial photography and field reconnaissance Regional Operations Coordinator 02 6586 8317 Heathland during incidents and the development of incident action plans. Limeburners Creek NR Hastings Area Office 02 6588 5555 These data are not guaranteed to be free from error or omission. The NSW National Parks and Wildlife and its employees Mount Seaview NR Pasture/non native species disclaim liability for any act done on the information in the data and any consequences of such acts or omissions. Koorebang NR Regional Office 02 6586 8300 This document is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research criticism or review, Rawdon Creek NR 02 6584 9402 (fax) as permitted under the copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Jasper NR Rural Fire Service Operations Officer Hastings 02 6586 4565 The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service is part of the Department of Environment and Conservation. -

Issue No. 174 March, 2021

Issue No. 174 March, 2021 News from the Wallamba Watershed is a Across The Fence March, 2021 - Circulation approx. 1010 - Nabiac, Krambach, Coolongolook & Bunyah Matthew Absalom Trades Qualified Business Machine Technician [email protected] 0401 160 485 New roofs Re-roofing Repairs Ridge capping Re-Pointing Roof ventilators Leaf guard Gutter & valley renewals Wallamba Computer Services m: 0418 285 951 Find us on Facebook e: [email protected] WHAT’S HAPPENING IN MARCH, 2021 Editorial. Hi all, Markets & Events. st A short month and it disappeared far too quickly. Haven’t been ● Bulahdelah (1st Sat) 1 8am to 1pm th sure whether to go out in summer clothes or just wear a raincoat • Blackhead Bazaar (1st Sun) 7 8am to 12 noon th and wellies and try to evade the hordes of mosquitoes at my place. • John’s River Country (2nd Sat) 13 9am to 1.30pm th The weeds are still going bonkers and there are a lot I haven’t seen • Wingham Community (2nd Sat) 8 th before that must have been hibernating for YEARS and just decided to • Myall Quays (3rd Sat) 15 9am to 1pm th fill my paddocks and yard with their “glory”. • The Hub Taree Showgnd (3rd Sat) 20 8am to 12 noon st Still haven’t been able to mow as the ground is just a soggy mire and • Krambach (3rd Sun) 21 8.30am to 1pm th the fire permit I got is due to expire on Friday so that was just a waste • NABIAC (Last Sat) 27 8am to 12 noon rd as everything is too wet to burn. -

The Fig Tree

THE FIG TREE JOURNAL OF THE MANNING WALLAMBA FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Inc. TAREE OPERATING SINCE 1985 IN PARTNERSHIP WITH MANNING VALLEY LIBRARIES No 133 February 2015 Postal Address: PO Box 48 Taree NSW 2430 ABN 50 373 809 536 Website: www.manningwallambafhs.com.au Email: [email protected] MANNING WALLAMBA FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Inc. Taree covers the whole Manning Region as shown in the above map and includes the following areas: Manning Valley, Wingham, Taree, Kendall, Coopernook, Old Bar, Forster, Harrington, Manning Point, Nabiac, Bulahdelah, Kew, Krambach, Oxley Island, Mitchells Island, Tinonee, Moorland, Lansdowne, Killabakh, Failford, Rawdon Vale, Tuncurry, Coolongolook, Bungwahl, Smiths Lake, Wallis Lake. OFFICE BEARERS President: G Rose Vice Presidents: G Toohey L Kidd Secretaries: S Robinson J Mitchell Treasurer: L Haynes V Fletcher Publicity: G Rose G Toohey Librarians J Mitchell C Troth Research: G. Toohey N. Swan Committee: I Hardy P Jarman L Kidd Public Officer: L Haynes President’s Report for February 2015 Dear all 139 Members, Firstly I would like to thank all those who attended the MWFHS Christmas Party at Club Taree. Thanks to Pam & co. for organising this event. As usual a good time was had by all talking about all things ancestral. Gifts were given to all who attended, courtesy of Nancye. When Life Membership was previously bestowed on Lyn McMartin, she was given a certificate but no badge. I took the opportunity of the Christmas Party to give Lyn a Life Membership badge which she has promised to wear at all times in the future. 2015 has started with exciting new Web pages at www.manningwallambafhs.com.au. -

Vegetation and Flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, Lower North Coast of New South Wales

645 Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. S.J. Griffith, R. Wilson and K. Maryott-Brown Griffith, S.J.1, Wilson, R.2 and Maryott-Brown, K.3 (1Division of Botany, School of Rural Science and Natural Resources, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351; 216 Bourne Gardens, Bourne Street, Cook ACT 2614; 3Paynes Lane, Upper Lansdowne NSW 2430) 2000. Vegetation and flora of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve, lower North Coast of New South Wales. Cunninghamia 6(3): 645–715. The vegetation of Booti Booti National Park and Yahoo Nature Reserve on the lower North Coast of New South Wales has been classified and mapped from aerial photography at a scale of 1: 25 000. The plant communities so identified are described in terms of their composition and distribution within Booti Booti NP and Yahoo NR. The plant communities are also discussed in terms of their distribution elsewhere in south-eastern Australia, with particular emphasis given to the NSW North Coast where compatible vegetation mapping has been undertaken in many additional areas. Floristic relationships are also examined by numerical analysis of full-floristics and foliage cover data for 48 sites. A comprehensive list of vascular plant taxa is presented, and significant taxa are discussed. Management issues relating to the vegetation of the reserves are outlined. Introduction The study area Booti Booti National Park (1586 ha) and Yahoo Nature Reserve (48 ha) are situated on the lower North Coast of New South Wales (32°15'S 152°32'E), immediately south of Forster in the Great Lakes local government area (Fig. -

Humanitarian Settlement Services Regional Profile #12 Coffs Harbour, New South Wales

Humanitarian Settlement Services Regional Profile #12 Coffs Harbour, New South Wales HSS Regional Profile #12 Coffs Harbor, New South Wales Contents Humanitarian Settlement Services 1 Contents 2 About Coffs Harbour 3 Service providers 4 Accommodation 4 Education 6 Health Services 7 Employment Opportunities 7 A welcoming community 9 DSS wishes to express its thanks to Anglicare North Coast for compiling this material. While every care has been taken, DSS makes no guarantees that the information provided is up to date. For further information on the Humanitarian Settlement Services programme see: Humanitarian Settlement Services (HSS) 2 HSS Regional Profile #12 Coffs Harbor, New South Wales About Coffs Harbour The North coast of NSW is divided into two areas – the Mid North Coast and the Northern Rivers. Coffs Harbour is part of the Mid North Coast region and is the major settlement location for new arrivals, with smaller numbers settling in Lismore in the north and Taree in the south. Coffs Harbour is approximately six hours’ drive north from Sydney and five and a half hours’ drive south from Brisbane. 3 HSS Regional Profile #12 Coffs Harbor, New South Wales Service providers Humanitarian Settlement Service (HSS) services provided in the region focus on helping refugees to gain access to mainstream services such as Centrelink, Medicare, banks, general and specialist health and medical services, English language tuition, training and employment, in addition to links to the community and community organisations. Anglicare North Coast is the service provider delivering services on behalf of the Department of Social Services (DSS) and has been providing community services to the NSW North Coast for over 12 years. -

Disability Inclusion Action Plans

DISABILITY INCLUSION ACTION PLANS NSW Local Councils 2018-2019 1 Contents Albury City Council 6 Armidale Regional Council 6 Ballina Shire Council 8 Balranald Shire Council 9 Bathurst Regional Council 9 Bayside Council 11 Bega Valley Shire Council 12 Bellingen Shire Council 14 Berrigan Shire Council 15 Blacktown City Council 16 Bland Shire Council 16 Blayney Shire Council 17 Blue Mountains City Council 19 Bogan Shire Council 21 Bourke Shire Council 21 Brewarrina Shire Council 22 Broken Hill City Council 22 Burwood Council 23 Byron Shire Council 26 Cabonne Shire Council 28 Camden Council 28 Campbelltown City Council 29 Canterbury-Bankstown Council 30 Canada Bay Council (City of Canada Bay) 31 Carrathool Shire Council 31 Central Coast Council 32 Central Darling Council 32 Cessnock City Council 33 Clarence Valley Council 34 Cobar Shire Council 36 Coffs Harbour City Council 37 Coolamon Shire Council 38 Coonamble Shire Council 39 Cootamundra-Gundagai Regional Council 40 Cowra Shire Council 41 Cumberland Council 42 Council progress updates have been Dubbo Regional Council 43 extracted from Council Annual Reports, Dungog Shire Council 44 either in the body of the Annual Report Edward River Council 44 or from the attached DIAP, or from progress updates provided directly via Eurobodalla Shire Council 44 the Communities and Justice Disability Fairfield City Council 46 Inclusion Planning mailbox. Federation Council 47 Forbes Shire Council 47 ACTION PLAN 2020-2022 ACTION 2 Georges River Council 49 Northern Beaches Council 104 Gilgandra Shire Council -

Taree Residential

What happens in Prepare yourself How the SES can help you Taree floods? Some basic measures you can take right now include keeping a The State Emergency Service is responsible for responding to list of emergency numbers near your telephone and assembling a floods in NSW. This includes planning for floods and educating Taree 5.70 1% Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP) flood level. A 1% AEP flood is a Home Emergency Kit. people about how to protect themselves and their property. flood which has a 1% chance of occurring or being exceeded in any one year. Floods greater than this height can occur and should be expected Your Home Emergency Kit should contain at all times: During flood the SES will provide flood information, safety advice • A portable radio with spare batteries and arrange for the delivery of essential supplies to people Better FloodSafe than Sorry 5.65 1929 peak height. Flood of record • A torch with spare batteries isolated by floodwater. Where appropriate, the SES will conduct • A first aid kit (with supplies necessary for your household) evacuations and flood rescue. 5.45 March 1978 peak flood height. Dumaresq Island, Glenthorne and • Candles and waterproof matches Taree Estate were totally flooded. Low-lying properties close to • A waterproof bag for valuables Browns Creek were inundated, including those in Beeton Pde, • Emergency contact numbers Crescent Ave, Stevenson St, Railway St and High St. Substantial www.ses.nsw.gov.au • A copy of any household emergency plans areas of the lower floodplain downstream of Taree are inundated 4.65 Taree Central Business District is likely to flood if this height is When flooding is likely, place in your Home Emergency Kit: exceeded. -

Macleay Valley Coast & Greater Port Macquarie Region

MACKSVILLE 14km For adjoining map see B TAYLORS ARM 4km C NAMBUCCA HEADS 27km Cartoscope's Coffs Harbour Tourist Map SCOTTS HEAD 7km D To Blackbird Flat YARRIABINI Grassy Camping Area 12km NEW ENGLAND GRASSY HEAD NAT PK SF 527 NATIONAL PARK Head HOLIDAY PARK 152º30'E 152º50'E 153º00'E 152º40'E 152º40'E 3 H MERA LGO RD i AL COMARA 8km, c k 14 TOURIST DRIVE 26km ARMIDALE 102km Bellbrook Mount RD 1 e era y gom Ck Yarrahapinni s All Yarrahapinni Stuarts Point WAY STUARTS POINT HOLIDAY PARK RD NAMBUCCA T Ck WAY IN TOOSE RD SF 470 O INGALBA P 1 Eungai 30º50'S Creek 8 TANBAN S FISHERMANS FISHERMANS TANBAN T NGAMBAA R BEND NR BEND SCA Ck A NATURE COUNCIL U T RESERVE RD RD RD S Goat Island Eungai YS RD JONES RD KA SF 527 Rail 23 c Creek Eungai (locality) YARRAHAPINNI Millbank M BANK WETLANDS Fishermans H NAT PK RANGE y Reach ALL RD RD T U a JA CK O AMENITIES AVAILABLE CK S S w SF RD R l i S RD MACLEAY DE A N RD RD a Freedom A R South West Collombatti RD S Andersons Island COLLOMBATTI Ck 526 Laggers Point SLIM Lookout Cedar Inlet Rocks Trial ARAKOON STARLING Park Kemps Bay RD SF 465 Tourist drive - sealed surface, unsealed...................................... Corner NAT PK Hickeys B RD 14 PHILLIP DR 1 DENNIS HUT Highway, major road................................................................. A1 U Eungai Arakoon D For detail 4 S RD see Map 2 Secondary road, tertiary road............................................... Saltwater RD C C Lagoon R OO Unsealed road, four wheel drive track...................................... -

Taree - Great Lakes Region Consultation Draft July 2014

Transport for NSW Regional Boating Plan Taree - Great Lakes Region Consultation Draft July 2014 Transport for NSW 18 Lee Street Chippendale NSW 2008 Postal address: PO Box K659 Haymarket NSW 1240 ISBN Register: 978 1 922030 68 9 www.transport.nsw.gov.au email: [email protected] © COPYRIGHT STATE OF NSW THROUGH THESECRETARY OF TRANSPORT FOR NSW 2014 Extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided the source is fully acknowledged. GHD | Report for Transport for NSW - Regional Boating Plan, 21/23122 | i Table of contents 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Physical character of the waterways .............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Manning catchment .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Wallis Lake ........................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Smiths Lake ......................................................................................................................... 9 3. Waterway users ........................................................................................................................... 10 3.1 Analysis of waterway users -

Manning Valley Destination Management Plan

Manning Valley Destination Management Plan September 2014 This Destination Management Plan (DMP) provides the framework for the development and management of our Manning Valley…naturally™ visitor destination. It is designed to facilitate and support visitation growth and encourage visitor expenditure in a manner that is sustainable and in line with community aspirations. Manning Valley Tourism ™ “ “ Manning Valley … naturally and the italic M swath device are trademarks of Greater Taree City Council (c) 2014, All Rights Reserved. Permission must be sought prior to reproduction or use. Manning Valley Destination Management Plan September 2014 2 ExecutiveContents Summary 4 About the Destination Management Plan 5 Destination Management Planning 6 Regional Economy 7 DESTINATION ANALYSIS 1.1 Key Destination Footprint 8 1.2 Key Stakeholders 8 1.3 Key Data and Documents 9 1.4 Key Assets 9 1.5 Key Imagery and Videography 11 1.6 Key Source Markets and Consumer Segments 11 1.7 Key Infrastructure 13 1.8 Key Communications Channels 14 DESTINATION DIRECTION 2.1 Focus 15 2.2 Vision 15 2.3 Mission 15 2.4 Marketing Analysis 16 2.5 Goals and Objectives 17 DESTINATION REQUIREMENTS 3.1 Human Resources 23 3.2 Financial Resources 23 3.3 Key Risks 23 Manning Valley Destination Management Plan September 2014 3 Executive Summary DESTINATION ANALYSIS The Manning Valley Destination Management Plan has been prepared in the context of the broader regional visions outlined in the North Coast Destination Network DMP and in line with the strategic priorities of the Visitor Economy Taskforce report. The key objectives in this plan are reflected in Council’s annual Operational Plan. -

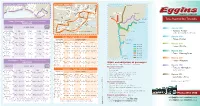

Taree Regional Bus Timetable

D R E YN O PEA S B RSO T M E N E D PL O P S E PO L C A T I T R R R GU E BE E M D T LB A O C D O T H C S UR O L NE M E D T S R T T R P E IV O E N B I B L A S U T NS T KY ET INDUSTRIAL ROAD AV H S S S G A IM D G A L E T P C N R L T R M RUSHBO I C X C B UN R T A L T M T S D L CL B A R L S F O S L A E E VIE A E IN W W TT A E G T T Y C Y ST S HARRINGTON ROAD N A to Taree K A E P L L U W L R O AV C A E H E O T E C E L O R K I L R T L M S S A T L O Z HARRINGTON - Route 320 WINGHAM - RouteE 319 ZA K R R M M C O R IN S O Lansdowne I VE I I D RI C N NT A IM A A D E R LATHAM AVE L R O R M R P REGIONAL MAP P ST S D O S F L O E N C T D T U E L R AL DA M R K T N R R L I C A S B A T K E Y N M A G A O S A S S P H N T NT P I L IM E L R H T SCOTT ST E T C T R S REE GRANTER ST S T T ST T C R R S R I IR N V E S IV E IN E E E R E U KE R T E H ST O B ST Q CH S N T G H A M BLVD N TT Y T PHINE Y A JOSE S RO PRICE NICHOLSON ST T S N L U R E W T ST E T R L E COODE ST E S S S T L T I E S S GLACKEN ST E E A B L BE Y CROWDY ST B BELL N T LL M L N A ST P T E S E INED B A BEACH ST D S T COMB MURRAY ST A L EAST Coopernook A S Taree O M ELE PILOT ST CL Y R CT B C RA O FA W U PD UN M RQ E TR UH O see Taree Timetable A A A Y R C R H L C ST UB D P R N D D OXLEY STREET E E R V CALEDONIA STREET E L E E CA Wingham B K NG U ST FA H ET RQ R N Q T UH T N A U E R BEACH STREET U S B O T ST B V B A R Harrington A W T N ILL Taree Regional Bus Timetable H IA O M S S S FO T P TH L ER N M I ING D A T HA A Taree to Harrington via Coopernook & Cundletown S M T R S ROAD S B K L UCESTER