We Shall Overcome? Bob Dylan, Complicity, and the March on Washington 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (And More)

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (and more) First, here’s another item for consideration by people who think that Pete Seeger was anti-Israel. (If you haven’t already, read Hillel Schenker’s recent post on this.) We have the permission of Gerry Magnes — active with the Albany, NY regional J Street chapter, who married into an Israeli family — to quote what he emailed the other day: Thought I would share a small anecdote my father in law once told me. He’s 95 and still living on a kibbutz (Kibbutz Evron) in the Western Galilee. Last winter, when my wife and I mentioned to him that we’d just attended a Pete Seeger concert . in Schenectady, . he related how he’d seen him perform (I think in Tel Aviv), probably in ’64. When he [Seeger] began to speak about the Israeli-Palestinian/Arab conflict at that time and his hopes for peace, he began to cry. He had to stop talking or singing for a bit until he could collect himself. The sincerity and depth of feeling left a deep impression on my father in law. http://www.cookephoto.com/dylanovercome.html Partners’ board chair Theodore Bikel goes back a long way with Seeger. They were part of the original board (with Oscar Brand, George Wein and Albert Grossman) that founded the Newport Folk Festival. This image captures a festival high point in 1963, with Theo and Seeger (at right) joining Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, the Freedom Singers and Peter, Paul and Mary to sing “We Shall Overcome.” Here’s Theo singing Hine Ma Tov with Seeger and Rashid Hussain (the latter identified as a Palestinian poet) from episode 29 of the 39-episode run of the “Rainbow Quest” UHF television series (1965-66), dedicated to folk music and hosted by Seeger: Upon hearing of Seeger’s passing, Theo wrote this on his Facebook page: An era has come to an end. -

This Production Is Made Possible by the Generosity of Peter House & Carol Childs. Busy Direct

PRESS CONTACT: Nancy Richards – 917-‐873-‐6389 (cell)/[email protected] MEDIA PAGE: www.northcoastrep.orG/press PHOTOS BY: Aaron Rumley FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE: FLAMBOYANT CIVIL WAR GENERAL CREATES HAVOC IN WORLD PREMIERE COMEDY, FADED GLORY, BY TIM BURNS AT NORTH COAST REP Performances BeginninG Wednesday, May 28, 2014 With OpeninG NiGht, Saturday, May 31, at 8 PM RunninG ThrouGh Sunday, June 22 Directed by DAVID ELLENSTEIN SOLANA BEACH -‐ Following its highly successful world premiere of MANDATE ME MORIES, North Coast Rep is mounting a second world premiere, FADED G LORY. Written by TimBurns, this comedic romp tells the improbable, but, true story of Daniel Sickels, a 19th-‐century congressman, friend to presidents, Civil War general, lover ofIsabella Queen II of Spain, notorious philanderer, embezzler, murderer,nd a the officer who almost cost the Union victory in perhaps the most pivotal battle of the Civil War, only to receive the Congressional Medal ofr. Hono Based on this real figure from American history, funny, poignant and filled with astonishing little-‐known historical information, FADED G LORY promises to be a highlight of our season. Audiences will enjoy a rollicking comedic romp through this amazing life. Artistic Director David Ellenstein* will directAndrew Barnicle,* Ben Cole, Frances Anita Rivera, Bruce Turk,* Rachel VanWormer, and Shana Wride.* Ryan Ford will be the assistant director. The design team includes Aaron Rumley,* Stage Manager; Marty Burnett, Scenic Design; Matt Novotny, Lighting; Sonia Elizabeth, Costumes; Melanie Chen, Sound; and Peter Herman, Hair & ign. Wig Des Peter Katz and Leon Williams are co-‐producers. *The actor orstage manager appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the union of professional actors and stage managers in the United States. -

1 Bob Dylan's American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, Through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory P

Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory Panel I Think I’ll Call It America Born into changing times, Bob Dylan shaped history in song. “Life’s a voyage that’s homeward bound.” So wrote Herman Melville, author of the great tall tale Moby Dick and one of the American mythmakers whose legacy Bob Dylan furthers. Like other great artists this democracy has produced, Dylan has come to represent the very historical moment that formed him. Though he calls himself a humble song and dance man, Dylan has done more to define American creative expression than anyone else in the past half-century, forming a new poetics from his emblematic journey. A small town boy with a wandering soul, Dylan was born into a post-war landscape of possibility and dread, a culture ripe for a new mythology. Learning his craft, he traveled a road that connected the civil rights movement to the 1960s counterculture and the revival of American folk music to the creation of the iconic rock star. His songs reflected these developments and, resonating, also affected change. Bob Dylan, 1962 Photo courtesy of John Cohen Section 1: Hibbing Red Iron Town Bobby Zimmerman was a typical 1950’s kid, growing up on Elvis and television. Northern Minnesota seems an unlikely place to produce an icon of popular music—it’s leagues away from music birthplaces like Memphis and New Orleans, and seems as cold and characterless as the South seems mysterious. Yet growing up in the small town of Hibbing, Bob Dylan discovered his musical heritage through radio stations transmitting blues and country from all over, and formed his own bands to practice the newfound religion of rock ‘n’ roll. -

Theodore Bikel Trivia Quiz

THEODORE BIKEL TRIVIA QUIZ by Marjorie Gottlieb Wolfe Syosset, New York Theodore Bikel, actor, activist, singer, and writer, has passed away at the age of 91. In the Foreword to his book, “Theo - The Autobiography of Theodore Bikel,” he wrote, “Most people lead two distinct lives--a private life and a public one. Others lead multiple lives; I am one of those. Professionally I can count three or four separate existences, politically three or four more. Add the personal aspects and altogether they add up to a cat’s count of nine.” Bikel said of “Fiddler” in a 2008 interview, “It’s a charming show. It’s a nice show. But it is what my wife calls ‘SHTETL LITE.’” Grab a #2 pencil and let’s see how well you fare on this not-so-serious Theodore Bikel Trivia Quiz. 1. While performing the role of Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof,” the following story took place: A new arrival to this country had never in his life seen a stage play. On his first day of leisure (“fraye tsayt”), he walked up to the ticket window (“fentster”) and asked the price of admission. “Downstairs, the tickets are $4.80,” explained the ticket clerk. “Upstairs, the price is $2.20.” “Is that so?” said the surprised immigrant? “Tell me, what’s playing upstairs?” A) True B) False 2. Which Yiddishist celebrated Bikel’s 85th birthday, which was held at Carnegie Hall? A) Michael Wex B) Ruth R. Wisse C) Uriel Weinreich D) Leo Rosten E) Miriam Weinstein 3. “Iz nisht gut tsu zayn aleyn” means, It’s not good to be alone. -

Recognition of Theodore Bikel's Years of Labor Service

RESOLUTION 26 Recognition of Theodore Bikel’s Years of Labor Service Submitted by Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO Referred to the Legislation and Policy Committee Theodore Bikel, better known as Theo, is the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, graduating the epitome of a Renaissance Man. Not with honors. In his first role in London’s famed content with a robust and diverse résumé as a West End theaters, Theo was directed by Sir multihyphenate performer, Theodore Bikel also Lawrence Olivier in A Streetcar Named Desire, leads a life committed to social justice. A longtime starring Vivien Leigh. In 1954, with a career in the labor leader and president of the Associated UK thriving, Theo received an invitation to appear Actors and Artistes of America, AFL-CIO (the 4 on Broadway in a play starring Louis Jourdan As) since 1988, Theo’s 55 years in the American titled Tonight in Samakand. For this role, Bikel labor movement are a testament to both the man earned his Actors’ Equity Association union card and the professional. A member of five different and, in his own words, “Little could they suspect AFL-CIO unions (Actors’ Equity Association, that, by doing so, they bought themselves a future American Federation of Musicians, American president for their own union.” Federation of Television and Radio Artists, Screen Actors Guild and American Guild of Variety Theo went on to an extremely active career Artists), Theo has never backed down from his in American theater. He starred in the world conviction that “working people as individuals are premiere of The Sound of Music, where he helpless and powerless unless they band together created the role of Captain von Trapp. -

WHERE WE COME from Our Jewish Heritage in Poland-- Past, Present & Future

WHERE WE COME FROM Our Jewish Heritage in Poland-- Past, Present & Future October 17-27, 2006 San Francisco Bay Area, California Presented by the Jewish Heritage Initiative in Poland, Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture EVENT REPORT Editor: Alice Z. Lawrence; Assistant Editor: Anna Goldstein WHERE WE COME FROM: Our Jewish Heritage in Poland— Past, Present & Future October 17-27, 2006 San Francisco Bay Area, California Presented by the Jewish Heritage Initiative in Poland, a partnership program of the Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture ROM OCTOBER 17 THROUGH 27, the Taube Francisco; Jewish Music Festival, East Bay Jewish Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Community Center; Judah L. Magnes Museum; F(TFJLC) in San Francisco held a series of cul- San Francisco Jewish Film Festival and Taube tural and academic events entitled “Where We Center for Jewish Studies, Stanford University. Come From: Our Jewish Heritage in Poland—Past Distinguished guests from Poland included Present & Future,” bringing Polish and American Dr. Eleonora Bergman, executive director, Jewish grantees to the San Francisco Bay Area. The festi- Historical Institute, Warsaw; Kate Craddy, proj- val’s fundamental message ects coordinator, Galicia was a revelation to many: “This is the first time, to my Jewish Museum, Krakow; that Jewish culture is being knowledge, that Jewish cultural Konstanty Gebert, journal- rediscovered and renewed renewal in Poland is the focus of ist/publisher of Midrasz by both Jews and Chris- attention here in the U.S. This is Magazine and Polish repre- tians in Poland and that the thanks to Tad Taube's extraordinary sentative of the TFJLC; flowering of these cultural, vision. -

THE JEWISH GEORGIAN July/August 2006 Jewishthe Georgian

JewishTHE Georgian Volume 17, Number 5 Atlanta, Georgia JULY-AUGUST 2006 FREE A legendary performer helps JTS start its 12th year What’s Inside Internationally renowned actor, musi- Gunderson, Kelly Jenrette, Chris Kayser, cian, and author Theodore Bikel will kick Joe Knezevich, and Hampton Whatley. off Jewish Theatre of the South’s 2006-07 In Spain in the year 1263, the King of season. Best known for creating the role of Aragon hosts a debate between Reb Moses A Family’s Loss Baron Von Trapp in the original Broadway Ben Nachman (Theodore Bikel) and Pablo After diabetes killed his son, a father production of The Sound of Music and por- Christiani (Chris Kayser), a Dominican became consumed with the need to find traying Tevye in over 2,000 performances friar. The very fate of Spain’s Jews hangs on a cure. of Fiddler On The Roof throughout the the rabbi’s ability to defend his faith with By Bobby Goldstein Sr. world, Mr. Bikel will present a staged read- words and with wit. It is a battle for the Page 15 ing and an intimate concert, September 11- freedom of a people, of a faith, and of the 14. human mind. On September 11-12, at 8:00 p.m., Mr. Tickets for The Disputation are $40. Ignorance Breeds Bikel will star in and direct the September 13-14, 8:00 p.m., Mr. Bikel Southeastern premiere of The Disputation continues his week-long JTS residency with Intolerance by Hyam Maccoby. Presented as a staged an intimate concert featuring musical selec- reading, the historical drama will feature tions from his expansive repertoire, includ- Israel is burdened by other nations’ mis- the all-star Atlanta cast of Carolyn Cook, perceptions. -

THEO BIKEL Celebrates 90 and 75 Years in Show Business Press Contact: with a New Edition of His Memoir, B

RELEASE THEO BIKEL Celebrates 90 and 75 years in Show Business Press Contact: with a New Edition of his memoir, B. Harlan Boll 626-296-3757 the release of 20 Albums on iTunes and [email protected] the theatrical release of “Theodore Bikel: In the Shoes of Sholom Aleichem” “To be with him is to be in the presence of greatness.”—Ed Asner Nonagenarian, Theodore Bikel, recently celebrated his 75-year in show business. Few have garnered such distinguished recognition in music, film, literature and stage. With the recent “New Edition” release of his memoirs, Rhino Records and Warner Music is releasing his records to iTunes and the highly anticipated release of “Theodore Bikel: In the Shoes of Sholom Aleichem” (co- written and performed by Theo Bikel and based on Sholom Aleichem’s writings from the immortal musical “Fiddler On The Roof”), now being screened on the festival circuit and to be release theatrical early next year. In addition, Theo is schedule to appear as Keynote speaker at the St Louis Jewish Book fair on opening night, Nov 2nd. “Theodore Bikel: In the Shoes of Sholom Aleichem” combines Bikel's charismatic storytelling and masterful performances with a broader exploration of shalom Aleichem's remarkable life and work. A pioneer of modern Jewish literature who championed and luxuriated in the Yiddish language, Sholom Aleichem created dozens of indelible characters. His Tevye the Milkman, Motl the Cantor's Son, and Menachem Mendl--"shtetl Jews" for whom humor and pathos were two sides of the same Yiddish coin--remain invaluable windows into pre-war Eastern European Jewish life, real and imagined. -

The Interview: No, the One with Theo Bikel

The Interview: No, the one with Theo Bikel PPI’s board chair, Theodore Bikel, is profiled in The Forward, Dec. 19 (“When the Legendary Theodore Bikel Turned 90“). Here’s a sample: An Interview with the ‘Fiddler’s’ Most Famous Tevye . Though he no longer treads the boards in his best-known stage role, Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof,” which he played for over two thousand performances, Bikel still performs on occasion. Most recently, at a 90th birthday celebration at the Washington Hebrew Congregation in Washington, D.C., he serenaded a crowd that included Sen. Pat Leahy of Vermont and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Bikel remains active in other arenas, as well. “Theodore Bikel in the Shoes of Sholom Aleichem,” a documentary that he produced and stars in, premiered this summer at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival, and he’s recently released an updated edition of “Theo: An Autobiography,” which was first published in 1994. Twenty years on from its original publication, “Theo: An Autobiography” remains a rollicking and fascinating read; it’s hard to think of another book that contains firsthand recollections of both the Anschluss — born in Vienna, Bikel emigrated from Austria to Palestine with his parents in 1938 — and Bob Dylan’s controversial “electric” set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. Amusing anecdotes abound regarding such career highlights as the original stage production of “The Sound of Music” and his roles in “The African Queen,” “The Defiant Ones,” and “My Fair Lady,” but the book also contains considerable soul-searching relating to Bikel’s changing relationship with Israel, his own feelings of statelessness, and his sense of guilt over having been able to escape the Holocaust while so many others perished at the hands of the Nazis. -

Gala Program ROBERT S

MOMENT’S VIRTUAL GALA 2020 RISING TO THE MOMENT! CELEBRATING 45 YEARS OF MOMENT’S INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM. Honoring Madeleine Albright, Emily Haber, Michel Martin, Max Brooks, Peter Lefkin & Calvin Trillin. With special guests David Brancaccio, Thomas Friedman, Malcolm Hoenlein, Ted Koppel, Gloria Levitas, Andrea Mitchell & Robert Siegel. “In an era when fact-free rants and racist slurs poison our national discourse, authentic journalism is more valuable than ever, yet harder to achieve. Moment does it in every issue. Its calm, well-informed voice of reason is a national treasure and an act of faith and courage.” —Glenn Frankel, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist ORDER OF EVENTS Pre-gala Program ROBERT S. GREENBERGER JOURNALISM AWARD Relax, learn about Moment & find unique gifts at momentmag.com/buynow2020 Michel Martin Introduction by Ted Koppel Award description by Scott Greenberger Film 45 Years Through the Lens of Moment Interview Robert Siegel interviews Madeleine Albright Welcome Robert Siegel, Master of Ceremonies Special Musical Performance Nadine Epstein, Moment Editor-in-Chief and CEO Jazz artist Dee Dee Bridgewater performs “Caravan” Awards Award COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP AWARD WOMEN AND POWER AWARD Peter Lefkin Madeleine Albright Introduction by Malcolm Hoenlein Introduction by Andrea Mitchell MITCHEL AND GLORIA LEVITAS LITERARY JOURNALISM AWARD Calvin Trillin Closing Remarks Introduction by Gloria Levitas Robert Siegel, Master of Ceremonies CREATIVITY AWARD Nadine Epstein, Moment Editor-in-Chief and CEO Max Brooks Introduction by David Brancaccio Post-gala Reception HUMAN RIGHTS AWARD Wind down and watch rehearsal outtakes from Max Brooks Ambassador Emily Haber Introduction by Thomas Friedman THIS EVENING IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MOMENT AWARD RECIPIENTS JUSTICE RUTH BADER GINSBURG, THEODORE BIKEL, LEON FLEISHER, ALLAN GERSON AND RABBI JONATHAN SACKS. -

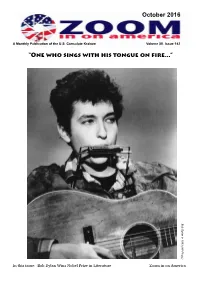

October 2016 “One Who Sings with His Tongue on Fire...”

October 2016 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume XII. Issue 142 “One who sings with his tongue on fire...” Photo) (AP 1963 in Dylan Bob e In this issue: Bob Dylan Wins Nobel Prize in Literature Zoom in on America THE FIRST MUSICIAN TO WIN THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE On October 13, 2016 the Swedish Academy issued a press release announcing that the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature is awarded to Bob Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Nobel prize winners are invited to Stockholm on December 10 to receive their awards from King Carl XVI Gustaf and to give a speech during a banquet. It is not yet known whether Bob Dylan will show up at the ceremony, but millions of his fans are looking forward to it. Take a little Bob Dylan quiz: a. composer b. performer 1. How many songs has Bob Dylan composed? c. singer a. between 50 and 100 d. poet b. more than 450 e. painter c. over 1000 f. writer g. poet-songwriter 2. Did Bob Dylan compose these songs? h. sculptor Look at the list below and write Yes or No. 4. In which of the films below has Bob Dylan appeared? a. Like a Rolling Stone b. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band a. Don’t Look Back, 1965 c. Blowin’ in the Wind b. Eat the Document, 1966 d. Knocking on the Heaven’s Door c. A Space Odyssey 1968 e. Scarborough Fair d. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, 1973 f. -

8542 Hon. Steven R. Rothman Hon. Kendrick B. Meek Hon

8542 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 151, Pt. 6 May 3, 2005 IN RECOGNITION OF THE NORTH Jersey Avalanche, and acknowledge the suc- man who has made his mark as an accom- JERSEY AVALANCHE YOUTH cess they have achieved, and the pride that plished musician, actor, author, lecturer, and HOCKEY TEAM; WINNERS OF THE they bring to the people of the great state of activist. Throughout his life, Theodore has 2005 USA HOCKEY TIER I CHAM- New Jersey. been committed to arts awareness, human PIONSHIPS IN THE 12 & UNDER f rights, and Jewish activism, and his service to DIVISION TRIBUTE TO THE LATE DR. the Los Angeles community and the world has HON. STEVEN R. ROTHMAN NSIDIBE N. IKPE been truly remarkable. OF NEW JERSEY Theodore was born in 1924, in Vienna, Aus- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HON. KENDRICK B. MEEK tria. At the age of 13, Theodore and his par- OF FLORIDA Tuesday, May 3, 2005 ents fled Austria to avoid Nazi persecution. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES They eventually settled in Palestine, where Mr. ROTHMAN. Mr. Speaker, I rise today Theodore began to develop a deep respect for with great pride to honor a tremendous group Tuesday, May 3, 2005 Jewish tradition and the performing arts. He of young people from the great state of New Mr. MEEK of Florida. Mr. Speaker, it is with Jersey, the North Jersey Avalanche PeeWee great pride—but with deep sorrow—that I rise soon began acting in the famous Habimah AAA youth hockey team. The Avalanche re- to pay tribute to the late Dr.