The Culture of Discretion - in Conversation with Archbishop of Brisbane, Mark Coleridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Charismatic Renewal Melbourne Thanking God for 50 Years of Grace

FEBRUARY 2021 Catholic Charismatic Renewal serving the Church The newsletter of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal. Melbourne, Australia. www.ccr.org.au Catholic Charismatic Renewal Melbourne thanking God for 50 years of grace YE ST T E IS R R D H A C Y T R O E D V A E Y R FO 1971-2021 ACROSS MY DESK PAGE 2 • THE ENDGAME OF TRANSGENDER IDEOLOGY IS TO DISMANTLE THE FAMILY PAGE 3 • MELBOURNE’S CURRENT OF GRACE - CATHOLIC CHARISMATIC RENEWAL PAGES 4-6 • 50TH CELEBRATION PAGE 7 • MEMORIES OF A WORKER IN GOD’S VINEYARD PAGES 8-9 • BOOK REVIEW PAGES 10-11 • 50 YEARS OF CHARISMATIC RENEWAL PAGE 11 • A WORD... FROM MIRIAM PAGE 12 • MARK YOUR DIARIES... PAGE 13 ACROSS MY DESK By LENYCE WILLASON As Jesus was coming up out of the water, For enquiries about Catholic Charismatic Renewal, its events or prayer groups visit the: he saw heaven being torn open and the Spirit descending on him like a dove. CCR CENTRE 101 Holden Street Mark 1:10 NRSV North Fitzroy There is no greater need that we have as individuals than to receive VIC 3068 (Car park entry in Dean Street) the gift of the Baptism of the Holy Spirit. It is by the Holy Spirit that we Telephone: (03) 9486 6544 are able to live as we long to live and are able to overcome the power Fax: (03) 9486 6566 of sin and guilt and fear within us. The most fundamental need of Email: [email protected] people is the gift of the Holy Spirit. -

Summary of the Plenary Meeting of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference Held at Mary Mackillop Place, Mount Street, North Sydney, Nsw

SUMMARY OF THE PLENARY MEETING OF THE AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC BISHOPS CONFERENCE HELD AT MARY MACKILLOP PLACE, MOUNT STREET, NORTH SYDNEY, NSW. 3 – 10 May 2012 The Mass of the Holy Spirit was concelebrated on Friday 4 May 2012 in the chapel of Mary MacKillop Place, North Sydney at 7 am. The President of Conference, Archbishop Philip Wilson, was the principal celebrant and preached the homily. The President welcomed the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Giuseppe Lazzarotto who was warmly greeted. He concelebrated the opening Mass, met Bishops informally, addressed the Plenary Meeting and participated in a general discussion. Archbishop Denis Hart was elected President and Archbishop Philip Wilson was elected Vice-President. Page 1 of 7 The following elections were made to Bishops Conference commissions. (Chair of the Commission is highlighted in bold) 1.Administration and Information 7. Health and Community Services +Gerard Hanna +Don Sproxton +Michael McKenna +Terry Brady +Julian Porteous +Joseph Oudeman ofm cap +Les Tomlinson +David Walker 2.Canon Law 8. Justice, Ecology and Development +Brian Finnigan +Philip Wilson +Vincent Long ofm conv +Eugene Hurley +Philip Wilson +Greg O’Kelly sj +Chris Saunders 3. Catholic Education +Greg O’Kelly sj 9.Liturgy +Timothy Costelloe sdb +Mark Coleridge +James Foley +Peter Elliott +Gerard Holohan +Max Davis +Geoffrey Jarrett 4. Church Ministry +David Walker 10. Mission and Faith Formation +Peter Comensoli +Michael Putney +Peter Ingham +Peter Comensoli +Vincent Long ofm conv +Peter Ingham +Les Tomlinson +Julian Porteous +William Wright 11. Pastoral Life 5. Doctrine and Morals +Eugene Hurley +George Pell +Julian Bianchini +Mark Coleridge +Terry Brady +Tim Costelloe sdb +Anthony Fisher op +Anthony Fisher op +Gerard Hanna +Michael Kennedy 6. -

Padua News Padua News Is the Official Quarterly Newsletter of St

Padua News Padua News is the official quarterly Newsletter of St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church Cnr Exford & Wilson Roads, Melton South, VIC 3338 Tel: 03 9747 9692; Fax: 03 9746 0422; Email: [email protected] This issue of Padua News is also published on the Parish Website http://stanthonysmeltonsouth.wordpress.com/padua-news/ Issue 46 December 1, 2017 From our ParishMessage Priest….. from Father Fabian In December 2010, we pur- generous donors, the figures were not exempt from the chased our present magnifi- arrived from Rome. We un- cares and trials of everyday cent nativity set. I can re- boxed them and set them life; from the moment of her up in the Holy Family conception, through her Father Fabian Smith member when I told the pa- Parish Priest rishioners in November Room and invited some pregnancy to journeying to 2009 that this nativity set children who were being Bethlehem to giving birth to cost $24,000, I heard a loud picked up by their parents Jesus in a stable, to finding gasp. But that gasp did not after school to come and refuge in Egypt, to living a have the first look. Each simple life in Nazareth, to deter us from going ahead to plan to purchase it at this one of them gasped in awe following Jesus to the foot of amount. I had asked for a upon seeing them. When the cross. Mary and Joseph’s sign from God as to whether God makes a promise he strong faith and deep trust in or not I should go ahead keeps it. -

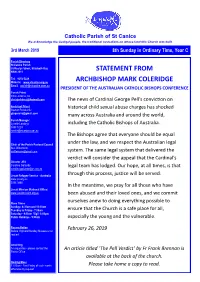

Statement from Archbishop Mark Coleridge

Catholic Parish of St Canice We acknowledge the Gadigal people, the traditional custodians on whose land this Church was built. 3rd March 2019 8th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year C Parish Directory St Canice Parish 28 Roslyn Street, Elizabeth Bay NSW 2011 STATEMENT FROM Tel: 9358 5229 Website: www.stcanice.org.au ARCHBISHOP MARK COLERIDGE Email: [email protected] PRESIDENT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC BISHOPS CONFERENCE Parish Priest Chris Jenkins, SJ [email protected] The news of Cardinal George Pell’s conviction on Assistant Priest historical child sexual abuse charges has shocked Gaetan Pereira SJ [email protected] many across Australia and around the world, Parish Manager: Lynelle Lembryk including the Catholic Bishops of Australia. 9358 5229 [email protected] The Bishops agree that everyone should be equal Chair of the Parish Pastoral Council under the law, and we respect the Australian legal Sue Wittenoom [email protected] system. The same legal system that delivered the verdict will consider the appeal that the Cardinal’s Director JRS Carolina Gottardo legal team has lodged. Our hope, at all times, is that [email protected] Jesuit Refugee Service - Australia through this process, justice will be served. www.jrs.org.au 9356 3888 In the meantime, we pray for all those who have Jesuit Mission (National Office) www.jesuitmission.org.au been abused and their loved ones, and we commit Mass Times ourselves anew to doing everything possible to Sunday– 8:30am and 10:30am Tuesday to Friday– 7:00am ensure that the Church is a safe place for all, Saturday– 9.00am Vigil- 6:00pm Public Holidays– 9:00am especially the young and the vulnerable. -

Professor Zlatko Skrbiš Formally Installed As ACU Vice-Chancellor and President

MEDIA RELEASE 27/03/21 Professor Zlatko Skrbiš formally installed as ACU Vice-Chancellor and President Professor Zlatko Skrbiš was installed as Australian Catholic University’s fourth Vice-Chancellor and President at an installation Mass at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney on Friday 26 March. Most Rev Mark Coleridge, President of ACU Corporation, President of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, and Archbishop of Brisbane, was the principal celebrant, and Most Rev Anthony Fisher OP, Archbishop of Sydney delivered the homily. A performance of a Slovenian folk song ‘Zarja’ (‘Dawn’) preceded the ceremony. Due to COVID restrictions, members of Professor Skrbiš’s family were unable to travel from Slovenia to attend the Mass; they recorded the musical performance as a gift to him. Professor Skrbis pledged his commitment to leading the university as an ethical, enterprising organisation that would have an impact both within and across the communities in which it inhabits. “To be successful as a Vice-Chancellor in any university, you have to be good at all of the things you would expect of any Vice-Chancellor: prioritising the needs of our students, ethical leadership, commitment to research, effective administration, and the pursuit of excellence in all of our intellectual endeavours. “However, to be successful as a Vice-Chancellor at a Catholic university, you need to do all of that and also be very good at leading it in its Catholic endeavours. This is because a Catholic university is, by definition, part of the Church. Whilst having its own governance structures, it is genuinely part of the wider ecclesial mission of the Church in Australia and the world. -

Edwardstown Catholic Parish SAINT ANTHONY of PADUA

SAINT ANTHONY OF PADUA Edwardstown Catholic Parish Address: 832 South Road, Edwardstown, South Australia 5039 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0499 486 699 (message bank checked regularly– Website: www.edwardstowncatholic.net please note change to Parish Phone Number ) Facebook Page: StAnthonyofPaduaEdwardstownCatholicParish 21st/22nd March 2020 4th Sunday in Lent—Year A Parish Priest A few months ago, we were celebrating the joyous season of Christmas. There was one element that stands out during Christmas: the lights!! But why so many lights? To remind Father Phillip Alstin us that the Child in the manger is the Light of the world. Parish staff In this season of Lent, we shift our reflection from the Babe in the manger to the Man of Robyn Grave suffering on the Cross. Does his suffering and death mean that he ceases to be the Light? Parish Secretary No; his light penetrates even the deepest darkness of sin and death. The Cross lifts up the Light that all may see him and find hope in his mercy. Parish office hours Light is associated with the sense of sight, an important part Tuesday—1.30pm—4.15pm of our overall health. Today’s Gospel reminds us that Jesus, Wednesday 1.30pm—4.15pm the Light of the world, is a healer, bringing health to body and Thursday 1.30pm—4.15pm spirit. In giving sight to a man born blind, Jesus give him not Friday 1.30pm—4.15pm only bodily well-being but spiritual health as well. With the Weekend Mass suspended gift of physical sight, Jesus opens the window of the man’s church will be open at the soul, so that he can recognise Jesus. -

Bishops Commission for Church Ministry & National Council Of

Bishops Commission for Church Ministry & National Council of Priests of Australia Thursday 23 February 2017 Bishops Commission for Church Ministry Chairman: Bishop Peter Ingham Members: Archbishop Mark Coleridge Bishop Michael McCarthy Bishop Patrick O’Regan Bishop Leslie Tomlinson Bishop William Wright NCP Executive Chairman: Father James Clarke Members: Father Wayne Bendotti Father Bonefasius Buahendri SVD Father Mark Freeman Father Paddy Sykes The Royal Commission The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Sexual Abuse continues to haunt us. This month’s Catholic wrap up is particularly distressing because it is highlighting the extent of the criminal behaviour of clergy within our Church. Our people are the subject of derision and ridicule. The priesthood is held up to be a profession for paedophiles and degenerates. One of the unintended consequences of the Royal Commission is that it has condoned anti-Catholicism as the last legitimate prejudice left in Australia. In our press release, the executive of the N.C.P. declared our support for the initiatives of the Bishops of Australia in their endeavours to eradicate the scourge of sexual abuse which is a blight on our Church. We wish to reiterate our support for you and assure you of our prayers during this time of trial. The effect on clergy morale is palpable. However, we believe that we will come through this trial strengthened in our resolve to be a more compassionate Church. Questions we have for the bishops: • Will there be an investigation into the cultural factors which contributed to the sexual abuse crisis? • Will the bishops implement the recommendations of the Truth, Justice and Healing Council? Overseas Priests Ministering in our Dioceses There is a frustration amongst priests who have overseas assistant priests working with them in parish ministry. -

Bishop Mark Edwards Appointed to Wagga Wagga

AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC BISHOPS CONFERENCE Bishop Mark Edwards appointed to Wagga Wagga Media Release May 26, 2020 Pope Francis has this evening appointed Bishop Mark Edwards OMI the sixth Bishop of Wagga Wagga. Bishop Edwards, who will turn 61 next month, was born in Indonesia and grew up in Adelaide, Darwin and Melbourne’s southeast, attending St Leonard’s Primary School and Mazenod College. Mazenod was founded by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, the order he would eventually join. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1986 and has held leadership positions within the Australian Province of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. He was appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Melbourne on November 7, 2014 and ordained bishop the following month. Bishop Edwards’ priestly ministry has largely centred on secondary school and seminary education, including serving as rector of Iona College in Brisbane and as aspirants’ master and novice master at St Mary’s Seminary in Mulgrave. In addition to his priestly formation and theological training, Bishop Edwards completed a science degree at Monash University, where he also obtained a doctorate in philosophy. In a letter to the faithful of Wagga Wagga, Bishop Edwards described his appointment “as a call from God to be with you and journey with you as disciple, brother and bishop”. “Together, as a community of missionary disciples, we will worship, love and evangelise,” he said. “I am aware that I have much to learn, particularly about parish life and the joys and challenges of being a Catholic in Wagga Wagga. Keen to listen to your stories and those of the Diocese, I come humbly, with deep interest and love. -

Why the Delays in Appointing Australia's Bishops?

Why the delays in appointing Australia’s Bishops? Bishops for the Australian mission From 1788, when the First Fleet sailed into Botany Bay, until 31 March 2016, seventeen popes have entrusted the pastoral care of Australia’s Catholics to 214 bishops. Until 1976 the popes had also designated Australia a ‘mission’ territory and placed it under the jurisdiction of the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide which largely determined the selection of its bishops. The first five bishops never set foot on Australian soil. All English, they shepherded from afar, three from London, and two from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa where, from 1820 to 1832, they tendered their flock in distant New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land via priest delegates. The selection and appointment in 1832 of Australia’s first resident bishop, English Benedictine John Bede Polding, as Vicar Apostolic of New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land, was the result of long and delicate political and ecclesiastical negotiations between Propaganda, the British Home Secretary, the Vicars Apostolic of the London District and Cape of Good Hope, the English Benedictines, and the senior Catholic clerics in NSW. The process was repeated until English candidates were no longer available and the majority Irish Catholic laity in Australia had made it clear that they wanted Irish bishops. The first Irish bishop, Francis Murphy, was appointed by Pope Gregory XVI in 1842, and by 1900, another 30 Irish bishops had been appointed. Propaganda’s selection process was heavily influenced by Irish bishops in Ireland and Australia and the predominantly Irish senior priests in the Australian dioceses. -

Third Sunday of Lent 15 March 2020

Parish Activities in 2020 EMBRACING THE COMMUNITIES OF: BAPTISMS St Mary’s - South Brisbane; Saturday | 9.30 a.m. | monthly 1st Saturday St Francis’ St Ita’s - Dutton Park; 2nd Saturday St Mary’s St Francis of Assisi - West End & 3rd Saturday St Ita’s Our Lady of Perpetual Succour - Fairfield. Family preparation sessions on the fourth Tuesday of each month at 9.30 a.m. Bookings essential. Under the care of the Capuchin Franciscan Friars ADORATION Sunday: 4:00 p.m.—5:00 p.m. St Mary’s Church DIVINE MERCY Third Sunday of Lent Sunday: 4:15pm St Mary’s Church PRAYER AND QUIET REFLECTION 15 March 2020 - Year A Monday to Friday: 12:00 noon—2:00 p.m. at St Mary’s Church Dear Parishioners Parish notice regarding Coronavirus AWAKEN: TOGETHER IN CHRIST We welcome our Archbishop Mark Coleridge to our parish Directions have been issued from the Australian Catholic 1st Saturday of the month at 6:00 p.m. communities for the pastoral visit 2020. The purpose of this visit is Bishops Conference and the Archbishop of Brisbane and St Francis Hall, 47 Dornoch Terrace, West End to rejuvenate the energies of those engaged in evangelisation, the following protocols will be in place in our parish: website: awaken.org.au to praise, encourage and reassure them in their ministries. It is · Holy Communion from the chalice will not be given. ST FRANCIS TABLE—Ministry to the Elderly also an opportunity to invite the faithful to a renewal of Chris- Christ is fully present under either species. -

SEVENTEENTH SUNDAY in ORDINARY TIME 29Th JULY 2018

WELCOME TO SACRED HEART PARISH TATURA Fr Michael Morley – Parish Priest Sacred Heart – Tatura Telephone Tatura – 03 – 5824 1049 Parish Pastoral Council Fax Tatura – 03 – 5824 2745 In recess until further notice 2018 Email [email protected] Web www.sacredheartparishtatura.com.au https://www.facebook.com/sacredheartparishtatura As Christ’s disciples our mission is: * to be inspired by Christ Presbytery – 65 Hogan Street * to actively live out Christ’s message and the PO Box 110 TATURA 3616 Gospel values by respecting, celebrating and Mary Connelly-Gale – Secretary Marli Kelly - Administration Readings - honouring our Catholic traditions Year B * to provide welcome and sanctuary for all Mark * to foster a sense of social justice and to protect, We acknowledge the Yorta Yorta nation, the traditional custodians of the land on which we Weekday Year 2 nurture and support our Catholic community and meet today, as they have occupied the wider community by respecting life, self, and cared for this country for many others generations. We also celebrate and the environment. their continuing contributions to the life of this region. SEVENTEENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME 29th JULY 2018 WHAT COULD THE CHURCH LOOK LIKE IF WE Dear Prime Minister, LISTEN TO EACH OTHER? Confessional or Priest-Penitent Privilege (cont) You are invited to join an eConference group to talk Effect on people of faith about it! ‘Synodality in Practice - Listening to the Spirit and Leading Change’ ACBC - BBI eConference 2018 A wide range of citizens practice private Confession. Amongst Christians this includes all Time:10am - 2:30pm Western Catholics, Eastern Catholics and members When: Wednesday 8 August of the various Orthodox traditions. -

12-February.Pdf

BURLEIGH HEADS CATHOLIC PARISH PALM BEACH, Our Lady of the Way Church - Eleventh Ave, Palm Beach MIAMI, Calvary Church - Santa Monica Rd, Miami MUDGEERABA, St. Benedict's Church - Wallaby Dr, Mudgeeraba BURLEIGH HEADS COMMUNITIES - Burleigh Heads - INFANT SAVIOUR CHURCH, Park Av, Burleigh Heads - Burleigh Waters - Marymount College, Reedy Creek Rd, Burleigh Waters PARISH OFFICE: Mon - Fri 9.00am - 5.00pm Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time Office 5 Executive Pl, 2 Executive Dr, Burleigh Waters [PO Box 73 Burleigh Heads] 12 February, 2017 www.burleighheadscatholic.com.au Year A: Sirach 15:15-20; 1 Cor 2:6-10; Mt 5:17-37 Phone: 5576 6466 [also for After Hours] Fax: 5576 7143 New Bishop e-mail: [email protected] PARISH PASTORAL TEAM: We send our warm greetings and prayers to our Dean and PP of Surfers Fr Ken Howell - Parish Pastor Paradise, Fr Tim Harris, on the announcement by Pope Francis of his Fr Dantus Thottathil, MCBS - Associate Pastor appointment as the sixth bishop of Townsville. Bishop-elect Harris will bring Fr Stanley Orji - Associate Pastor Parish Business & Finance Manager wonderful pastoral skills to the northern diocese and will be welcomed by the Mr Jim Littlefield [email protected] people in a vast region of the Church. Speaking about his new appointment, Bishop-Elect Harris said, "I’m very conscious that the Diocese of Townsville has been without a bishop for three Parish Weekly Diary.... years. It has been on all of our minds. If the bishop is a sign of unity, which he is, I hope that I can strengthen the unity of the vast Diocese of Townsville and build Monday, 13 February on the work of Bishop Michael Putney and, since his death, on the efforts of 9.00am Mass - Miami Diocesan Administrator Fr Mick Lowcock." Tuesday, 14 February We offer our prayerful support to Fr Tim as he prepares for his Episcopal 7.00am Mass - Burleigh Heads Ordination, and for the people of Surfers as they look to the appointment of a new pastor.