UBCMJ Volume 11 Issue 2 | Spring 2020 2 EDITORIAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2013

Page 1 of 48 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2013 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aadhya 1 Abbigayl 1 Acrom 1 Aadvika 1 Abbrianna 18 Ada 1 Aadya 17 Abby 1 Adabell 1 Aaesha 3 Abbygail 1 Adahlia 1 Aafarida 2 Abbygale 1 Adair 2 Aahana 1 Abeeha 1 Adalaya 1 Aahna 1 Abeera 1 Adalayne 1 Aaiana 2 Abegail 2 Adalee 2 Aaira 1 Abelia 1 Adaleyah 1 Aaisha 1 Abemael 1 Adali 1 Aalaiyah 1 Aberdeen 4 Adalia 1 Aaleen 1 Abha 1 Adalina 2 Aaleyah 1 Abhitha 1 Adaline 5 Aaliya 2 Abi 17 Adalyn 42 Aaliyah 1 Abiah 19 Adalynn 1 Aaliyah-Faye 3 Abigael 4 Adalynne 1 Aamina 164 Abigail 2 Adama 3 Aaminah 1 Abigail-Crystal 1 Adamay 2 Aamna 2 Abigale 1 Adan 9 Aanya 1 Abigayl 3 Adanna 1 Aara 4 Abigayle 3 Adara 3 Aaradhya 1 Abigia 1 Adarah 1 Aaralee 1 Abiha 1 Adasyn 1 Aaralynn 1 Abira 1 Adaya 1 Aaria 1 Abisatou 2 Addalyn 1 Aarieanna 1 Abisha 1 Addalynn 1 Aarika 3 Abrianna 1 Addasyn 4 Aarna 1 Abrie 1 Addelinn 1 Aarohi 1 Abriela 1 Addelyn 1 Aarushi 2 Abriella 3 Addie 5 Aarya 7 Abrielle 1 AddieMae 1 Aaseas 1 Abril 1 Addilia 1 Aashna 1 Abryanna 1 Addiline 1 Aasia 1 Abul 2 Addilyn 1 Aasiya 1 Aby 1 Addin 1 Aavry 1 Abyelle 1 Addington 1 Aayah 2 Abygail 1 Addisen 1 Aayat 1 Abygeil 74 Addison 1 Aayla 3 Acacia 7 Addisyn 1 Aazeen 3 Acadia 3 Addley 1 Abagael 1 Acelin 11 Addyson 2 Abagail 1 Acelynn 1 Adeeb 1 Abaigeal 1 Achad 3 Adeena 4 Abbey 1 Achan 1 Adeife 1 Abbi 1 Achette 2 Adela 3 Abbie 1 Achiraya 1 Adelaida 1 Abbiegale 1 Achoi 13 Adelaide 7 Abbigail 1 Achok 8 Adele 1 Abbigaile 1 Achols 1 Adelène 1 Abbigale 1 Acil 1 Adelie Page 2 of 48 Baby Girl Names Registered -

List of Registered Voters

LIST OF REGISTERED VOTERS I, Linda Rothery, County Clerk and Ex-Officio Registrar for Churchill County, Nevada, do hereby certify the following is a true and correct list of the active registered voters of the County of Churchill as appears on the register of voters in my office as of September 8, 2020. I hereby request every registered voter to examine the list carefully and if any omissions, misplacements or other irregularities in the list are found, please contact my office and have the same corrected. If you have moved since the last election and have not notified my office, please do so immediately at 775-423-6028 or [email protected]. You may also update your registration at: www.registertovotenv.gov FIRST NAME LAST NAME MIDDLE NAME PRECINCT AAS JEFFREY ALLAN 4 ABABNEH LUAI NABEEH 5 ABBE MARIAN LESLIE 18 ABBOTT ANNE CHELSEA 16 ABBOTT MATTHEW 1 ABBOTT RONALD JAMES 19 ABBOTT‐YOST MARGARET LYNNE 15 ABE MELINDA MARIE 9 ABE KOBE A 9 ABE BRYSON ARLO 9 ABE‐ MARTINEZ KAYLL A 16 ABE MOYLE TAYLOR IWTSWY 9 ABERCROMBIE CYNTHIA S. 7 ABERCROMBIE WILLIAM F. 7 ABERLE KAREN MARIE 19 ABERLE DAVID MICHAEL 19 ABERNATHY BRIANNA RAE LEINA'ALA 6 ABERNATHY ROBERT ALLEN 6 ABERNATHY STEVEN WOODS 19 ABERNATHY THERESA MARRY 19 ABITIA PHYLLIS 2 ABITIA AUGUST JOE 2 ABLES VELVA LOU 7 ABOYTES GLORIA 2 ABOYTES JUAN BERNARDO 2 ABOYTES WHITNEY PAIGE 1 ABOYTES‐RAMIREZ DANIEL 1 ABRAHAMSEN FAYE E. 8 ABSHIRE MATTHEW JEFFREY 6 ABSHIRE TAMMI LEANN 6 ABUHENDI DESIREE 13 ACHATZ MARIA L. 15 ACHUFF PRECIOUS MORNING DOVE 16 ACHURRA NORMA JOAN 2 ACHURRA ROBERT J. -

Last Name First Name City State Province Region Abbate Christine Carol Stream IL Abbate Dawn Silver Lake WI Abbinante Trisha ST

Last name First name City State province region Abbate Christine carol stream IL Abbate Dawn Silver Lake WI Abbinante Trisha ST CHARLES IL Abbott Renee Naperville IL Abcarian Ariane River Forest IL Abe Allison Naperville IL Abens Erin Aurora IL Abraham Sarah FRANKFORT IL AbrahamsonAmanda NAPERVILLE IL Abromitis Barbara GLEN ELLYN IL Abruscato Ashley Oswego IL Accettura Lori MONTGOMERY IL Acker Christine Wheaton IL Acosta Griselda ADDISON IL Acup Fawn Joliet IL Adam Mary Michelle Rockford IL Adams Lin Aurora IL Adams Abigail ELBURN IL Adams Sharyn Indian Head Park IL Adams Jennifer Oswego IL Adams Nian Naperville IL Ader Suzan Morris IL Adolfo Theresa Aurora IL Adorjan Emily Wheaton IL Afryl Carmen Woodridge IL Agarwal Radhika Forest Park IL Agarwal Reema Naperville IL Aggarwal mamta Naperville IL Agpalo Michele Evanston IL Agran Erica Chicago IL Agrawal Ruchi NAPERVILLE IL Aguirre Mary yorville IL Agyepong Tera OAK PARK IL Ahmad Sahar OAK BROOK IL Ahmed Suhayla GLENDALE HTS IL Akhter Sofia Naperville IL Alampi Rochelle Elgin IL Alavi Aimun NILES IL Albert Katie Wheaton IL Albertini Lauryn Naperville IL Albertini Robyn Naperville IL Albrecht Pamela Naperville IL Alcantar Hallie Oswego IL Alcantar Victoria BLUE ISLAND IL Alcantara Lorena Naperville IL Aldrich Dana Naperville IL Ales Cathy Bolingbrook IL Alexa Suzanne Shorewood IL Alexander Jennifer Schaumburg IL Ali Mona Naperville IL Ali Azka Schaumburg IL Allamian Cyndi St. Charles IL Allbright Callie Baton Rouge LA Allen Tarah OSWEGO IL Allen Ava Naperville IL Allen Sunny NAPERVILLE IL -

Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019

Vital Statistics Baby2019 BabyGirl GirlsNames Names | Registered in 2019 From:Jan 01, 2019 To: Dec 31, 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Aadhini 1 Aarnavi 1 Aadhirai 1 Aaro 1 Aadhya 2 Aarohi 2 Aadila 1 Aarora 1 Aadison 1 Aarushi 1 Aadroop 1 Aarya 3 Aadya 3 Aarza 2 Aafiya 1 Aashvee 1 Aaghnya 1 Aasiya 1 Aahana 2 Aasiyah 2 Aaila 1 Aasmi 1 Aaira 3 Aasmine 1 Aaleena 1 Aatmja 1 Aalia 1 Aatri 1 Aaliah 1 Aayah 2 Aalis 1 Aayara 1 Aaliya 1 Aayat 1 Aaliyah 17 Aayla 1 Aaliyah-Lynn 1 Aayna 1 Aalya 1 Aayra 2 Aamina 1 Aazeen 1 Aamna 1 Abagail 1 Aanaya 1 Abbey 4 Aaniya 1 Abbi 1 Aaniyah 1 Abbie 1 Aanya 3 Abbiejean 1 Aara 1 Abbigail 3 Aaradhya 1 Abbiteal 1 Aaradya 1 Abby 10 Aaraya 1 Abbygail 1 Aaria 2 Abdirashid 1 Aariya 1 Abeeha 1 Aariyah 1 Aberlene 1 Aarna 3 Abhideep 1 Abi 1 Abiah 1 10 Jun 2020 1 Abiegail 02:22:21 PM1 Abigael 1 Abigail 141 Abigale 1 1 10 Jun 2020 2 02:22:21 PM Baby Girl Names | Registered in 2019 First Name Frequency First Name Frequency Abigayle 1 Addalyn 4 Abihail 1 Addalynn 1 Abilene 2 Addasyn 1 Abina 1 Addelyn 1 Abisha 2 Addi 1 Ablakat 1 Addie 2 Aboni 1 Addilyn 3 Abrahana 1 Addilynn 2 Abreen 1 Addison 61 Abrielle 2 Addisyn 2 Absalat 1 Addley 1 Abuk 2 Addy 1 Abyan 1 Addyson 2 Abygale 1 Adedoyin 1 Acadia 1 Adeeva 1 Acelynn 1 Adeifeoluwa 1 Achai 1 Adela 1 Achan 1 Adélaïde 1 Achol 1 Adelaide 20 Ackley 1 Adelaine 1 Ada 23 Adelayne 1 Adabpreet 1 Adele 4 Adaeze 1 Adèle 2 Adah 1 Adeleigha 1 Adair 1 Adeleine 1 Adalee 1 Adelheid 1 Adalena 1 Adelia 3 Adaley 1 Adelina 2 Adalina 2 Adeline 40 Adalind 1 Adella -

2014 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 The Library FOUNDATION’s PURPOSE The purpose of The Library Foundation is to ensure the future of the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library as an indispensable community resource. We do this by helping secure financial resources to support collections, programs, services, technology and physical facilities of the library. The Library Foundation pursues this purpose by seeking philanthropic support, providing conscientious stewardship of the assets in its care, encouraging appropriate community partnerships and advocating on behalf of the library’s mission. The Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library is the sole beneficiary of funds raised by The Library Foundation. ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... THE LIBRARY FOUNDATION | 1515 SW 10TH AVENUE | TOPEKA, KS 66604-1374 | 785 580-4498 | FOUNDATION.TSCPL.ORG ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Your Support Makes a Difference We know that our library is so much more than books. Because of tax -

Spring 2020 Commencement Program Book

Spring 2020 Fayetteville, Arkansas Contents: Commencement Program – 3 The Academic Procession – 4 The Official Party – 5 Notes on Ceremony – 6 Honorary Degree Recipient – 7 Degree Candidates – 8 Senior Scholars – 25 Past Honorary Degree Recipients – 82 Board of Trustees – 84 Colleges: Graduate School – 3 School of Law – 21 Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences – 27 Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design – 36 J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences – 38 College of Education and Health Professions – 50 College of Engineering – 57 Sam M. Walton College of Business – 68 2 GRADUATE SCHOOL SPRING 2020 2 THE ACADEMIC PROCESSION Chief Marshal and Bearer of the Mace Candidates for Specialist Degrees The Official Party Candidates for Master’s Degrees Faculty of the University Candidates for Juris Doctor Degrees Candidates for Doctoral Degrees Candidates for Baccalaureate Degrees Chief Marshal and Bearer of the Mace Stephen Caldwell, Chair of the Campus Faculty Associate Professor, Music Marshals Adnan A. K. Alrubaye, Research Assistant Douglas D. Rhoads, University Professor, Professor, Biological Sciences Biological Sciences and Poultry Science Barbara B. Shadden, University Professor Emerita, Valerie H. Hunt, Associate Professor, Rehabilitation, Human Resources and Political Science Communication Disorders Charles Leflar,Clinical Professor, Kate Shoulders, Associate Professor, Accounting Agricultural Education, Communication and Harry Pierson, Assistant Professor, Technology Industrial Engineering Anna Zajicek, Professor, Sociology and Criminology Banner Carriers Nancy Arnold, Director of Credit Studies, John M. Norwood, Professor, Global Campus Accounting Kristopher R. Brye, Professor, Graduate School and Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences International Education Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Gary Prinz, Associate Professor, Life Sciences Civil Engineering Alphonso W. -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019 -

FIRST NAME MI LAST NAME HONORS CITY STATE NATION Chad Darrell Abbott * MISSOULA MT Amanda J

FIRST NAME MI LAST NAME HONORS CITY STATE NATION Chad Darrell Abbott * MISSOULA MT Amanda J. Ackerman ** BILLINGS MT Jessica M. Adair * CORVALLIS MT Troy Elliot Adam * BILLINGS MT Katherine N. Adams * BOZEMAN MT Brittany Jo Adams ** CORVALLIS MT Rachel Elizabeth Adams * GREAT FALLS MT Jessica Marie Adams * MISSOULA MT Rebecca Diane Adamski * MISSOULA MT Molly Mackenzie Adamson * HELENA MT Amber Kim Adcock * LOLO MT Abbey Kristine Adkison * WHITEHALL MT Haley June Adney * KALISPELL MT Florent Aerts * TOULON FR FRANCE Wyley Thomas Agamenoni * WOLF CREEK MT Tomi Rae Ahearn * MISSOULA MT Emily Treise Ahern ** SUNFISH LAKE MN Gabriel John Ahl * MEDICAL LAKE WA Dalen James Aichlmayr * HELENA MT Jourdyn Margaux Aiken * ENCINITAS CA Victoria E. Ainsworth ** ASHLAND OR Caitlin Mackenzie Ajax * MISSOULA MT Isaac Oluwayemisi Akinola * OSOGBO NIGERIA Alison Claire Albers * MISSOULA MT Adam Waesche Alessi * MISSOULA MT Muriah Laurise Alexander * DEER LODGE MT Emily Katherine Alexander * FRENCHTOWN MT Susan L. Alexander * MISSOULA MT Jacqueline Dy Alfafara * MISSOULA MT Saleh Hamed Alharthi ** MISSOULA MT Abdulaziz Abdulrauf Aljama ** DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA Nicole Tara Allen * KALISPELL MT Rebecca Anne Allen * OROVILLE CA Victoria Louise Allen * CONWAY AR Luke Morgan Allgeyer * GANDEEVILLE WV Jacob Roy Allington ** FLORENCE MT Courtney Jean Allinson * EAST HELENA MT Kristina Nicole Allinson ** FORT RUCKER AL Eliza Katherine Allison * HELENA MT Julia Louise Allred * HAMILTON MT Jeremy Scott Allred * MISSOULA MT Jessica Lynn Hofhiens Allred * MISSOULA MT Sarah J.Kryn Alsup * DEER LODGE MT Stuart Whitney Alsup * KALISPELL MT Robert David Alt * ONTARIO CA Lance William Altmaier * MISSOULA MT Fallon Larissa Alvarez * HOWELL NJ Jonathon Stuart Ambarian * FRAZIER PARK CA Alexandra Eleanor Ambelang * HAMILTON MT Christopher Nelson Amen ** SAN ANTONIO TX Kaitlin J. -

“B” Honor Roll Simley High School 2019-2020 Last Name/First Name/Grade

TRIMESTER 3 “B” HONOR ROLL SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL 2019-2020 LAST NAME/FIRST NAME/GRADE Almanza Banos Emily 9 Jennings Leah 9 Alvarez Karla 9 Kahlhamer Brynae 9 Amundson Carlee 9 Kleckner Ayla 9 Anderson Hannah 9 Kluender Blake 9 Anderson Jada 9 Komatsu Sunshine 9 Barklow James 9 Leckas Ioannis 9 Bergum Abigail 9 Lencowski Sydney 9 Blevins Thalia 9 Little Madelyn 9 Bloch Carly 9 Longoria Castor Rosa 9 Bondgien Monica 9 Lopez Julian 9 Brummund Samantha 9 Lynner Alexa 9 Bungert Robynne 9 Maltos-Perez Getsemani 9 Bursey Samuel 9 Mendele Michael 9 Collins Hunter 9 Morvari Brandon 9 Contreras Melanee 9 Mulugeta Kalab 9 Cortez Esau 9 Ngo Han 9 Cowart Ramya 9 Novotny Aaliyah 9 Curry Anajae 9 O'Brien Brianna 9 DeJesus Anthony 9 Ostebo Micah 9 Difronzo Erin 9 P'Simer Aidan 9 Eckstrom Erika 9 Pechacek Emily 9 Ellis Samuel 9 Prelgo Hailey 9 Erdrich Amaya 9 Radmaker Parker 9 Erickson Alexander 9 Redner Kylie 9 Eschbach Jonathan 9 Reeck Aydan 9 Faria Chloe 9 Remackel Reid 9 Garcia Abigail 9 Rivera Samuel 9 Gregg Ethan 9 Rivera Sigfredo 9 Hamed Anwar 9 Rodriguez Fierro Alex 9 Hjelm Alex 9 Romero Cortina JoEllen 9 Iguanero Roth Zackary 9 Campos Fernando 9 Rubendall Glenn 9 Ingebrigtsen Emma 9 Salazar Isabella 9 Iverson Colin 9 Salvador Angel 9 Jacobsen Riley 9 Shungu Chance 9 Jeffers Abigail 9 Skappel Ashleigh 9 Jenkins Olivia 9 Smith Dezmond 9 TRIMESTER 3 “B” HONOR ROLL SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL 2019-2020 LAST NAME/FIRST NAME/GRADE Smith Isabelle 9 Sok Alysa 9 Somvong Ethan 9 Thibodeau Oscar 9 Tighe Anna 9 Torres Leonel 9 Tuccitto Isabella 9 Valdez Alexandra 9 -

Can Laser Doppler Flowmetry Evaluate Pulpal Vitality in Traumatized Teeth?

Can laser Doppler flowmetry evaluate pulpal vitality in traumatized teeth? THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Meghan D. Condit, D.D.S. Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2015 Master's Examination Committee: Dennis McTigue, D.D.S., M. S. (Advisor) Ashok Kumar, B.D.S., M.S. Kumar Subramanian, B.D.S., M.S. Dimitris Tatakis, D.D.S., Ph.D. Copyright by Meghan D. Condit, D.D.S. 2015 Abstract Background/Aim: Vascular supply is the most accurate measure of tooth vitality but current sensibility tests use indirect measures of subjective neural response. This study aimed to evaluate Laser Doppler Flowmetry for the assessment of pulp vitality in traumatized permanent teeth in a pediatric population. Materials and Methods: A Laser Doppler Flowmeter was used to measure blood flow in a total of 194 teeth from 51 subjects (mean age 10.1; range 6 to 16 years). Teeth were categorized into groups including revascularized (n=8), traumatized (n=85) and control (n=101). Blood flow was measured with the PeriFlux System 5000 Laser Doppler Perfusion Monitor using probe (PH 407-6) and affixed to each tooth. Tests were repeated for each erupted permanent incisor in the same arch as control. Subjects were followed to evaluate traumatized teeth for pulpal status and necrotic teeth were confirmed clinically with endodontic therapy. Results and Conclusions: Among traumatized teeth, there was no difference in pulpal blood flow based on pulp diagnosis (P=0.08). -

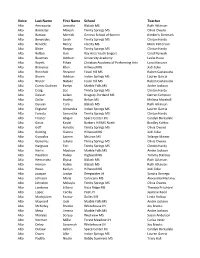

Voice Last Name First Name School Teacher

Voice Last Name First Name School Teacher Alto Amesquita Jannette Blalack MS Ruth Atkinson Alto Bannister Maleah Trinity Springs MS Olivia Owens Alto Barrow Merrick Geneva School of Boerne Kimberly Denmark Alto Benavides Sarah Trinity Springs MS Clinton Hardy Alto Bendele Bailey Liberty MS Mark Patterson Alto Blake Raegan Trinity Springs MS Clinton Hardy Alto Bolton Auri Bay Area Youth Singers Carol Barwick Alto Bowman Addison University Academy Leslie Hooe Alto Boyett Ethan Christian Academy of Performing Arts Lora Maeurer Alto Bravenec Ellen Hillwood MS Jodi Coke Alto Breinholt Breanne Fossil Hill MS Ruben Castanuela Alto Brown Addison Indian Springs MS Lauren Garcia Alto Bryner Natalie Fossil Hill MS Ruben Castanuela Alto Cortez Godinez Evelyn Marble Falls MS Andre Jackson Alto Craig Zoe Trinity Springs MS Clinton Hardy Alto Deleon Leilani Gregory-Portland MS Darren Campion Alto Dollar Hadley Belton MS Melissa Marshall Alto Duncan Cora Blalack MS Ruth Atkinson Alto England Alexandra Indian Springs MS Lauren Garcia Alto Foresta Samantha Trinity Springs MS Clinton Hardy Alto Froster Abigail Space Center Int. Carolyn Barksdale Alto Garza Kaylei Barbers Hill MS North Bradley Kohles Alto Goff Hynslee Trinity Springs MS Olivia Owens Alto Golding Gianna Hillwood MS Jodi Coke Alto Gonzalez Lauren McLean MS Solange Mainer Alto Gutierrez Juliana Trinity Springs MS Olivia Owens Alto Hargrave Tori Trinity Springs MS Clinton Hardy Alto Harris Madison Marble Falls MS Andre Jackson Alto Hazelton Hailey Highland MS Tammy Stallcup Alto Hernandez Elyssa