Carlingford Lough Special Protection Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Louth County Council

Louth County Council Establishment of Groundwater Source Protection Zones Ardee Water Supply Scheme Curraghbeg Borehole January 2012 Revision 4 Prepared by: Gerry Baker, WYG Ireland In collaboration with: Geological Survey of Ireland And in Partnership with: Louth County Council With contributions from: Natalya Hunter Williams, GSI PROJECT DESCRIPTION Since the 1980’s, the Geological Survey of Ireland (GSI) has undertaken a considerable amount of work developing Groundwater Protection Schemes throughout the country. Groundwater Source Protection Zones are the surface and subsurface areas surrounding a groundwater source, i.e. a well, wellfield or spring, in which water and contaminants may enter groundwater and move towards the source. Knowledge of where the water is coming from is critical when trying to interpret water quality data at the groundwater source. The Source Protection Zone also provides an area in which to focus further investigation and is an area where protective measures can be introduced to maintain or improve the quality of groundwater. Louth County Council contracted the GSI to delineate source protection zones for nine groundwater public water supply sources in Co. Louth. The sources comprised Ardee, Cooley (Carlingford and Ardtully Beg), Collon, Termonfeckin, Omeath (Lislea Cross and Esmore Bridge), Drybridge and Killineer. This report documents the delineation of the Ardee source protection zones. A suite of maps and digital GIS layers accompany this report and the reports and maps are hosted on the GSI websites (www.gsi.ie). Geological Survey of Ireland Ardee Public Water Supply Groundwater Source Protection Zones TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 2 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................ 1 3 LOCATION, SITE DESCRIPTION AND WELL HEAD PROTECTION ......................................... -

Visit Louth Brochure

About County Louth • 1 hour commute from Dublin or Belfast; • Heritage county, steeped in history with outstanding archaeological features; • Internationally important and protected coastline with an unspoiled natural environment; • Blue flag beaches with picturesque coastal villages at Visit Louth Baltray, Annagassan, Clogherhead and Blackrock; • Foodie destination with award winning local produce, Land of Legends delicious fresh seafood, and an artisan food and drinks culture. and Full of Life • ‘sea louth’ scenic seafood trail captures what’s best about Co. Louth’s coastline; the stunning scenery and of course the finest seafood. Whether you visit the piers and see where the daily catch is landed, eat the freshest seafood in one of our restaurants or coastal food festivals, or admire the stunning lough views on the greenway, there is much to see, eat & admire on your trip to Co. Louth • Vibrant towns of Dundalk, Drogheda, Carlingford and Ardee with nationally-acclaimed arts, crafts, culture and festivals, museums and galleries, historic houses and gardens; • Easy access to adventure tourism, walking and cycling, equestrian and water activities, golf and angling; • Welcoming hospitable communities, proud of what Louth has to offer! Carlingford Tourist Office Old Railway Station, Carlingford Tel: +353 (0)42 9419692 [email protected] | [email protected] Drogheda Tourist Office The Tholsel, West St., Drogheda Tel: +353 (0)41 9872843 [email protected] Dundalk Tourist Office Market Square, Dundalk Tel: +353 (0)42 9352111 [email protected] Louth County Council, Dundalk, Co. Louth, Ireland Email: [email protected] Tel: +353 (0)42 9335457 Web: www.visitlouth.ie @VisitLouthIE @LouthTourism OLD MELLIFONT ABBEY Tullyallen, Drogheda, Co. -

Irish Water Report

Irish Water Report Natura Impact Statement to inform the Appropriate Assessment of the Proposed Sewerage Scheme at Omeath, Co. Louth Contents Introduction 4 Legislative Context 4 Source-Pathway-Receptor Model 5 Guidance Followed 6 Stages Involved in the Appropriate Assessment Process 7 Methodology 8 Desktop Study 8 Field Ecological Surveys 8 Consultation 8 Screening 9 Introduction 9 Description of Project 9 Project Background 9 Construction Methodology 10 Description of the Existing Environment 14 Wastewater Treatment Plant Location 14 Outfall Pipe 15 Water Quality in Carlingford Lough 16 Identification of Relevant Natura 2000 Sites 17 Potential Adverse Effects on the Natura 2000 Sites 23 Overview of potential impacts of the new sewerage scheme 23 Potential direct impacts 24 Potential indirect impacts 24 2 | Irish Water NIS – Omeath Sewerage Scheme Possible Cumulative Impacts with other Plans and Projects in the Area 25 Screening Assessment 25 Screening Conclusions 30 Stage 2: Appropriate Assessment 31 Description of the Natura 2000 Site Potentially Affected 31 Description of the Qualifying Interests of the SAC 31 Conservation Objectives of the Carlingford Shore SAC 32 Annual Vegetation of Drift Lines 33 Perennial Vegetation of Stony Banks 33 Impact Prediction 34 Direct Adverse Effects 34 Indirect Adverse Effects 35 In-Combination / Cumulative Effects 35 Mitigation Measures 36 Mitigation by Avoidance 36 Construction Phase Mitigation 36 Marine Mammals, Otters , Annex IV species and other protected fauna 37 Biosecurity 37 Monitoring 38 Conclusion Statement for Appropriate Assessment 38 Plates 39 3 | Irish Water NIS – Omeath Sewerage Scheme Introduction This report comprises an Appropriate Assessment Screening and Natura Impact Statement (NIS) for the proposed sewerage scheme at Omeath, Co. -

Open Space, Recreation & Leisure

PAPER 10: OPEN SPACE, RECREATION & LEISURE CONTENTS PAGE(S) Purpose & Contents 1 Section 1: Introduction 2 Section 2: Definition & Types of Sport, Recreation & 2 Open Space Section 3: Regional Policy Context 5 Section 4: ACBCBC Area Plans – Open Space Provision 14 Section 5: Open Space & Recreation in ACBCBC 18 Borough Section 6: Outdoor Sport & Children’s Play Space 22 Provision in Borough Section 7: Passive & Other Recreation Provision 37 Section 8: Existing Indoor Recreation and Leisure 37 Provision Section 9: Site Based Facilities 38 Section 10: Conclusions & Key Findings 45 Appendices 47 DIAGRAMS Diagram 1: Craigavon New Town Network Map (cyclepath/footpath links) TABLES Table 1: Uptake of Plan Open Space Zonings in ACBCBC Hubs Table 2: Uptake of Plan Open Space Zonings in ACBCBC Local Towns Table 3: Uptake of Plan Open Space Zonings in other ACBCBC Villages & Small Settlements Table 4: Borough Children’s Play Spaces Table 5: 2014 Quantity of playing pitches in District Council Areas (Sports NI) Table 6: 2014 Quantity of playing pitches in District Council Areas (Sports NI: including education synthetic pitches and education grass pitches) Table 7: No. of equipped Children’s Play Spaces provided by the Council Table 8: FIT Walking Distances to Children’s Playing Space Table 9: Children’s Play Space (NEAPS & LEAPs) within the ACBCBC 3 Hubs and Local Towns Tables 10 (a-c): ACBCBC FIT Childrens Playing space requirements Vs provision 2015-2030 (Hubs & Local Towns) Tables 11 (a-c): ACBCBC FIT Outdoor Sports space requirements Vs provision -

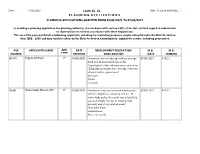

PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED from 01/05/2021 to 07/05/2021

Date: 11/05/2021 Louth Co. Co. TIME: 11:58:58 AM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 01/05/2021 To 07/05/2021 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION M.O. M.O. NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 20/339 Eugene McKeon P 14/05/2020 Permission for new dry agricultural storage 07/05/2021 418/21 shed and all associated site works. *Significant Further Information received on 15/04/2021 provides for, inter alia, retention of hard surface gravel area* Mollyrue Collon Co Louth 20/401 Hunterstown Rovers GFC P 12/06/2020 Permission for proposed new training pitch 07/05/2021 422/21 with floodlighting consisting of 8 no. 16 meter high poles (4 to each side of pitch) & associated light fittings at existing club grounds and all associated works Pairc Baile Fiach Hunterstown Ardee, Co Louth Date: 11/05/2021 Louth Co. Co. TIME: 11:58:58 AM PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 01/05/2021 To 07/05/2021 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. -

1. Introduction

chapter title 7 1. INTRODUCTION Northern Ireland has a close connection with outlined in the first UK Government report on the sea. We have over 650 kilometres of marine stewardship, Safeguarding our Seas(1) coastline and our largest towns are associated and is particularly relevant to Northern Ireland. with ports. As an island society, the sea has always had an important role to play, offering The sea is not a limitless resource and as a source of recreation and a place of work to pressure on our marine area grows, so does many. Fishing communities depend upon the the potential for conflict between different sea for their livelihoods and shipping forms activities. These activities vary in their a vital bridge for commerce with the wider compatibility with each other and the extent to world, sustaining our ports and relying on safe which they affect the marine environment. navigation through our waters. Therefore, we need to develop an approach to The sea is home to an amazing variety regulating these activities so as to allow their of marine life, some of which are found sustainable management. It is for this reason nowhere else in the world. The seabed is that the UK Government and the Devolved an archaeological repository of our maritime Administrations are developing policies that heritage; in the future it could also be an will provide a framework for a new system of important source of minerals. Increasingly, marine planning. there are new pressures in our marine environment. The growing demand for ‘green’ In Northern Ireland this framework will be energy drives the search for new ways to achieved through 3 interlocking pieces of harness the power of tides, waves and offshore legislation presented in Table 1.1. -

2. Marine Biodiversity

chapter title 15 2. MARINE BIODIVERSITY Brittlestars. Ophiothrix fragilis, Red Bay, Co Antrim Key messages • More than half of Northern Ireland’s What is biodiversity? biodiversity is found beneath the sea. Biodiversity (biological diversity) is a term • Northern Ireland has a rich marine used to describe the variety of life found in biodiversity due to its position at a junction the environment including plants, animals and of cold northern and warm southern waters. micro-organisms, the genes that they contain • Many of our marine species and habitats are and the ecosystems that they form. considered to be in a good state. • Some important marine habitats have been It is a little known fact that approximately 50% damaged by mobile fishing gear. of Northern Ireland’s biodiversity lies below • The Northern Ireland Government the sea, largely regarded as out-of-sight and Departments have a responsibility to restore out-of-mind (1). Simply put, marine biodiversity damaged habitats to favourable condition. concerns the whole variety of life found in • Enhanced protection of marine biodiversity our seas and oceans, from the largest whales will be delivered through the Northern to the smallest bacteria. Most importantly, Ireland Marine Bill by designating Marine marine biodiversity plays a fundamental role in Protected Areas. maintaining the balance of life on our planet. • More marine monitoring and research is required to understand the complex marine What do we know about marine biodiversity environment fully. in our own seas? • There is an important role for coastal The first recorded survey of Northern Ireland’s communities in biological recording; rich marine biodiversity dates back to 1790 research is not solely the preserve of when systematic dredging of the seabed government agencies and can be carried out was being conducted by the naturalist in partnership with volunteers. -

Carlingford Lough Boat Trail

Carlingford Lough Boat Trail LOUGHS AGENCY EARNING A WELCOME 1. Please be friendly and polite to local residents and other water users. 2. Drive with care and consideration and park sensibly. 3. Change clothing discreetly (preferably out of public view). 4. Gain permission before going on to private property. 5. Minimise your impact on the natural environment and use recognised access points. There are many unofficial access points which could be used with the owner’s consent. 6. Be sensitive to wildlife and other users regarding the level of noise you create. 7. Observe wildlife from a distance and be aware of sensitive locations such as bird nest sites, bird roosts, seals on land and wintering wildfowl and wader concentrations. 8. Follow the principles of ‘Leave No Trace’. For more information visit:- www.leavenotraceireland.org 9. Keep the numbers in your party consistent with safety, the nature of the water conditions and the impact on your surroundings. 10. Biosecurity: sailors must help stop the spread of invasive species threatening our waterways and coasts! Wash and thoroughly dry boats, trailers and all other kit after a trip. Desiccation is effective against most invasive species, countering their serious environmental and economic impacts. WILDLIFE Carlingford Lough is frequented by otters and seals. In 2016, a bow head whale was spotted off the mouth of the lough and basking shark and dolphin have been reported. Boat fishing for Tope (a shark) and other species is popular in the area. Waders and wildfowl (often breeding in the arctic) winter here, feeding on mudflats as the tide recedes. -

Sanitary Survey Review for Strangford Lough

Sanitary Survey Review for Strangford Lough Produced by AQUAFACT International Services Ltd On behalf of The Food Standards Agency in Northern Ireland March 2021 Aquafact International Services Ltd. 12 Kilkerrin park Tuam Road Galway city www.aquafact.ie [email protected] Table of Contents Glossary ......................................................................................................... 1 1. Executive Summary................................................................................. 5 2. Overview of the Fishery/Production Area ............................................. 7 2.1. Location/Extent of Growing/Harvesting Area .......................................... 7 2.2. Description of the Area ......................................................................... 11 3. Hydrography/Hydrodynamics .............................................................. 15 3.1. Simple/Complex Models ....................................................................... 15 3.2. Depth .................................................................................................... 16 3.3. Tides & Currents ................................................................................... 18 3.4. Wind and Waves................................................................................... 30 3.5. River Discharges .................................................................................. 35 3.6. Rainfall Data ......................................................................................... 39 3.6.1. Amount -

Greencastle Village Renewal Plan

January 2018 Greencastle Village Renewal Plan Newry, Mourne and Down District Council Greencastle Aerial View | Credit: Heritage Ulster GREENCASTLE VILLAGE RENEWAL PLAN Contents Section 01 Introduction 2 Section 02 Context 4 Section 03 Policy Analysis 7 04 Consultation Process 11 Section 05 Site Analysis 13 06 Opportunities 15 Section 07 Implementation 22 00 08 Action Plan 23 Greencastle 1 GREENCASTLE VILLAGE RENEWAL PLAN 01 Introduction The Village Renewal Plan has been developed by the community in conjunction with Newry, Mourne and Down District Council to meet the requirements of the Rural Development Programme for Northern Ireland 2014-2020. Ove Arup and Partners (Arup) was appointed as the consultancy team to facilitate the delivery of the Village Renewal Plan for Jonesborough. This Village Renewal Plan has been facilitated by a stakeholder workshop. The outcome of this is a Village Renewal Plan which includes a range of projects and initiatives that we believe will have a real impact on the area. The Village Renewal Plan was funded under Priority 6 (LEADER) of the Northern Ireland Rural Development Programme 2014-2020 by the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs and the European Union, and Newry, Mourne and Down District Council. The Rural Development Programme uses the LEADER approach which adopts a community led model to assist rural communities to improve the quality of life and economic prosperity in their local area, through the allocation of funds based on local need. Village Renewal and Development is an important element of the Rural01 Development Programme. The Village Plan is a working document that requires the support of the community and in many cases the community working in partnership with other agencies and statutory bodies. -

Louth County Archivesfor Upper Dundalk Barony—Six Esq

COUNTY OF LOUTH. A COPY OF THE 0BACC©UUTIB F©E QUERIES , AND THE PRESENT MENTS GRANTED, B Y THE (Srantl Juti of the (Bmmttj of South, AT SPRING ASSIZES, 18-56. HELD AT D1JMI»ALR, I N AND FOR SAID COUNT Y, F or the F iscal Business of same, on T uesday, the 26th day of February, 1856, and for General Gaol Delivery, on Wednesday Louth County27th day of February,!85 Archives6 . JUDGES; The Right Hon. David Richard Pigot, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer; and The Hon. Philip Cecil Crampton, second Justice of the Clueen’s Bench. -....... ■■ DUNDALK , PRINTED BY JAMES PARKS, EARL-STREET. 1856. PUBLIC ORDER S . GRAND JURY. 6, and 7, William IV., Chapter 110, Section, 3 . We appoint that Presentment Sessions shall be held at the following THOMAS LEE NORMAN, Esq , Foreman, times and places, and for the following Baronies, between the hours of JOHN M'CLINTOCK, E sq ., T w e l v e o’Clock at noon, and F iv e o’Clock i n the afternoon, of each day FREDERICK J OHN FOSTER, E s q ., respectively, preparatory to the next General Assizes, pursuant to the Act, 6 and 7 William the 4th, Chapter 116, Section 3. RICHARD MACAN, E s q ., WILLIAM RUXTON, E sq , At Ardee on Monday, the 28 th April, 1856, for Ardee Baroby, JOHN MURP HY, Esq., At Carlingford on Tuesday, the 29th April 1856, for L o w e r Dundalk do. EDWARD TIPPING, Esq., At Dunleer on Y/ednesday, the 30th April .*856, for Ferrard Barony, At Dunleer on Wednesday, the 30th April 1856, for Drogheda Barony, FRANCIS DONAGH, Esq., At Louth on Friday, the 2nd May 1856, for Louth Barony THE HON. -

The Down Rare Plant Register of Scarce & Threatened Vascular Plants

Vascular Plant Register County Down County Down Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register and Checklist of Species Graham Day & Paul Hackney Record editor: Graham Day Authors of species accounts: Graham Day and Paul Hackney General editor: Julia Nunn 2008 These records have been selected from the database held by the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording at the Ulster Museum. The database comprises all known county Down records. The records that form the basis for this work were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Cover design by Fiona Maitland Cover photographs: Mourne Mountains from Murlough National Nature Reserve © Julia Nunn Hyoscyamus niger © Graham Day Spiranthes romanzoffiana © Graham Day Gentianella campestris © Graham Day MAGNI Publication no. 016 © National Museums & Galleries of Northern Ireland 1 Vascular Plant Register County Down 2 Vascular Plant Register County Down CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 Conservation legislation categories 7 The species accounts 10 Key to abbreviations used in the text and the records 11 Contact details 12 Acknowledgements 12 Species accounts for scarce, rare and extinct vascular plants 13 Casual species 161 Checklist of taxa from county Down 166 Publications relevant to the flora of county Down 180 Index 182 3 Vascular Plant Register County Down 4 Vascular Plant Register County Down PREFACE County Down is distinguished among Irish counties by its relatively diverse and interesting flora, as a consequence of its range of habitats and long coastline.