A Revision of the Ancient Woodland Inventory for Sevenoaks District, Kent Report and Inventory Maps August 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESSA Secondary Schools Team Championships

ESSA Secondary Schools Team Championships - 2019 National Finals are to be held at London Aquatic Centre, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, E20 2ZQ (50 metre pool) on Saturday 16th November. JGFREEJunior Girls Freestyle Relay IGFREEIntermediate Girls Freestyle Relay SGFREESenior Girls Freestyle Relay 1 Mount Kelly; Tavistock SW 2.00.11 1 Mount Kelly; Tavistock SW 1.45.50 1 Mount Kelly; Tavistock SW 1.45.78 2 Tonbridge Grammar; Tonbridge School SE 2.01.96 2 Millfield School; Street SW 1.50.45 2 Millfield School; Street SW 1.46.11 3 Taunton School; Taunton SW 2.02.26 3 Ellesmere College; Ellesmere WM 1.52.71 3 Plymouth College; Plymouth SW 1.48.07 4 Penistone Grammar; Sheffield NE 2.02.55 4 Devonport High School for Girls; Plymouth SW 1.53.04 4 Walthamstow Hall; Sevenoaks SE 1.52.06 5 Mayflower High School; Billericay Ea 2.03.07 5 Sheffield High School; Sheffield NE 1.54.05 5 St Felix School; Southwold Ea 1.53.01 6 Sevenoaks School; Sevenoaks SE 2.03.23 6 St Teresas; Effingham SE 1.54.96 6 Cherwell; Oxford SE 1.53.12 7 Sheffield High School; Sheffield NE 2.03.57 7 St Felix School; Southwold Ea 1.55.20 7 Bromley High; Bromley Lo 1.53.29 8 Wycombe High School; High Wycombe SE 2.03.75 8 Stroud High School; Stroud SW 1.56.09 8 Reigate Grammar; Reigate SE 1.53.70 9 The Abbey School; Reading SE 2.04.21 9 The Abbey School; Reading SE 1.56.28 9 StHelen&StKatharine; Abingdon SE 1.54.06 10 Guildford High; Guildford SE 2.04.34 10 Wycombe Abbey School; High Wycombe SE 1.56.76 10 Parkstone Grammar; Poole SW 1.54.64 11 Lady Eleanor Holles School; Hampton -

Progress Summary

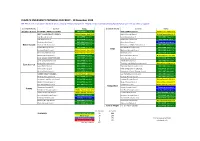

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 10 December 2019 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council Campaign in progress West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge -

The IB at Sevenoaks 2018 LR.Pdf

The Sixth Form at Sevenoaks is large, Every student in the Sixth Form at Sevenoaks ‘ Sevenoaks is best cosmopolitan and exciting, comprising over is encouraged to be curious, creative, critically 400 students from more than 40 countries aware, and to develop his or her talents to around the world. All of our Sixth Formers the full. Life is fast-paced and dynamic, and known for pioneering pursue the International Baccalaureate expectations are high. Diploma Programme, which the school has delivered for over 40 years. The IB Diploma At the same time, we try to cultivate in our the ib and for being a represents, in the school’s view, the best pupils the habit of reflection, and the school’s preparation for university and the world international outlook promotes understanding strongly international of work. and open-mindedness. The IB has rapidly established itself as the Our strong pastoral ethos supports expert gold standard of world education. The IB is teaching, and a broad range of co-curricular school – not just in its not just an exam board, however; it embodies opportunities complements the academic a philosophy of education based on a few courses on offer, preparing our students for basic principles: leadership in an increasingly complex world. intake but in its outlook ’ l students should be both literate and Katy Ricks the Good schools Guide numerate, scientifically adept as well as linguistically able, and not abandon key subjects at the age of 16; l education is about more than passing exams; it involves promoting creativity in the arts, well-being through sport, and compassion through service in the community; l schools have a responsibility for advancing a clear set of values, including international-mindedness, integrity and honesty, and tolerance towards others. -

Mole Valley Local Development Framework

Appendix A Sevenoaks District Local Development Framework The Future of Sevenoaks District Local Plan Policies beyond September 2007 The Sevenoaks District Local Plan was adopted in March 2000. All the policies in the Sevenoaks District Local Plan were saved for a period of three years from the commencement of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act on 28th September 2004 until 27th September 2007. No Local Plan policies will be replaced by policies in the Core Strategy or other new Development Plan Documents before 27th September 2007. The Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) issued a protocol for saving adopted Local Plan policies beyond the initial three-year saved period in August 2006. It sets out the criteria that Local Plan policies must meet if they are to have their life extended beyond September 2007. The Council must submit a list of all those Local Plan policies that it wishes to extend and those it does not wish to save, with reasons, to the Secretary of State, through the Government Office for the South East (GOSE), by 1st April 2007. The following two tables list all the Sevenoaks District Local Plan policies. The first table lists those saved Sevenoaks District Local Plan policies that the Council wishes to continue to use beyond September 2007, together with reasons. The second table lists those saved Local Plan policies that the Council does not wish to save beyond September 2007 with reasons. Saved Sevenoaks District Local Plan policies the Council wishes to extend beyond the three-year saved period Consistent with - Regional Policy – RPG9 & The Policy Title South East Plan (SEP), Reasons for wishing to extend policy The Community Plan (CP) Chapter 4 Environment EN1 Development Yes, PPS1 (Delivering The policy is consistent with national and regional policy on the design of Control - Sustainable Development) development set out in PPS1. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. Principal Area Boundary Review Borough of Gravesham/Borough of Dartford/District of Sevenoaks LOCAL GOVEHNICWT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND HEK)hT NO. LOCAL GOVKRflUEJlT BOI'NJJAHY COMMISSION FOR CHAIRMAN Mr C J Ellerton CMC MB1C Mr J U Powell PRICE FGV* Lady Aoknur lir T Brockbank DI^ Professor G E Cherry Mr K J L Newell Me B Qcholee QBE THE RT. HON. PATRICK JENKIN MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT 1. At present the New Barn residential area is split between Dartford Borough, Sevenoaks District and Gravesham Borough; the part situated in Dartford is in the parish of ^outhfleet; the part in Sevenoaks is in the parish of Longfield, whilst the part in Gravesham is unparished. On 30 November 1979» Gravesham Borough Council requested ue to review the boundaries between the districts of Gravesham, Dartford and Sevenoaks in the vicinity of New Barn. Their request was in response to representations from the New Barn Ratepayers Association for the whole of the New Barn residential area to be incorporated within Gravesham Borough. The Association based their representations on a survey of opinion which they carried out in 1978 among the residents of New Barn on the question of whether the area should be under one authority, and if so, which one. The results indicated that a majority (8?#) of residents indicating a view preferred to see New Barn under one authority and a large proportion (6990 of these considered that this should be Gravesham. 2. We noted that Kent County Council, Dartford Borough Council, Sevenoaks District Council, and Longfield Parish Council were all opposed to a review beinp undertaken at that time, although Kent County Council and Dartford BOrough Council did a^ree that the current boundaries in the New Barn area were not wholly satisfactory. -

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment DGS

1 Kent Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment Dartford, Gravesend, Swanley and surrounding areas co-terminus with Dartford, Gravesham & Swanley CCG The accompanying maps etc. in Appendix A should be viewed alongside this document Kent PNA 2018- DGS CCG area Final version March 2018 2 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Transport Links ................................................................................................ 8 Pharmaceutical Services in the area ................................................................ 8 Healthy Living Pharmacies ............................................................................ 14 Housing .......................................................................................................... 15 Kent PNA 2015 – Dartford, Gravesham and Swanley area ........................... 16 Consultation ................................................................................................... 16 Conclusions and recommendations Kent PNA 2018 DGS area .................... 17 Document Version Control ............................................................................. 18 Kent PNA 2018- DGS CCG area Final version March 2018 3 Introduction This document has been written as part of the main Kent Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment (PNA) to allow judgements to be made using local data. This document should be read in conjunction with the main Kent PNA. The area consists of 3 main towns, Dartford, Gravesend -

Holiday Extra

From the M23 Junction 9 Brighton Crawley - 1 Follow the M23 overpass at Junction 9 and take the A23 Brighton A 3 Crawley 21 exit toward Airport 7 A2 - 2 Following signs to North Terminal go straight over M23 TO N Gatwick R LONGBRIDGELONGBRIDGE M25 JCt 7 E Gatwick the first roundabout ROUNDABOUTROUNDABOUT I G A E. Grinstead (A23) T D - 3 At the 2nd roundabout take the 4th exit signposted A E B R O R (M23) R S S A I G 3 A23 Crawley/Redhill D 5 2 H 9 CRO 3 T 2 Y O N M - 4 After joining the A23 Northbound, get into the right POVE Gatwick R 4 O hand lane A (A23) C D D H A R R L D - 5 At the roundabout take the 4th exit signposted A23 W O O AIRPORTAIRPORT WAYWAY ROUNDABOUTROUNDABOUT M23 Crawley/Brighton (you should now be travelling in the Junction 9a A 2 direction you have just come from) 3 1 NORTHNORTH 3 Crawley A I R - 6 Stay on the A23 southbound and go straight on at TERMINALTERMINAL P O R T W M23 D AY R the first roundabout Y E AIRPORTAIRPORT WAYWAY L 2 R ROUNDABOUTROUNDABOUT - 7 At the second roundabout take the 2nd exit for O M23 H EASTEAST Junction 9 Lowfield Heath/Charlwood RVP North Terminal Long Term NORTH - 8 After 200 yards take the 1st exit at the mini SSOUTHOUTH Air cargo Air Cargo Airport other areas TERMINALTERMINAL GATWICKGATWICK roundabout (Charlwood Road) 3 Redhill A23 North 2 AIPORTAIPORT - 9 Airparks is 1.5 miles ahead on the right hand side Terminal A LONDON GATWICK Crawley South From the M23 Junction 10 Airport RVP SOUTH D AIRPORT Other areas Redhill Terminal - 1 From the M23 overpass at Junction 10 take the exit proud to park your car General Aviation Terminal A Station A23 O R signposted Horsham (A2011) Airparks Gatwick N - 2 At the first roundabout take the 3rd exit signposted O Charlwood Road, Lowfield Heath T H A2011 Horsham (A23) Crawley, West Sussex, RH11 0QB Town Centre A23 3 G 3 I Horsham (A264) 2 - Next, you come to a roundabout with traffic lights. -

Waste Collection Commitment Signatories

Signatories to the Waste Collection Commitment North East Eastern Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council Peterborough City Council Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Fenland District Council Hartlepool Borough Council Tendring District Council Darlington Borough Council Maldon District Council Gateshead Council Colchester Borough Council Durham Council Chelmsford Borough Council Middlesbrough Council Castle Point Borough Council North Tyneside Borough Council Braintree District Council North Norfolk District Council North West St Edmundsbury Borough Council Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Forest Heath District Council Hyndburn Borough Council Central Bedfordshire Council Fylde Borough Council South Cambridgeshire District Council Blackburn with Darwen Council Southend-on-Sea Borough Council Cheshire East Council Dacorum Borough Council Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council Broadland District Council Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council Hertsmere Borough Council Wyre Borough Council South Ribble Borough Council East Midlands Stockport Council Chesterfield Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council West Midlands Charnwood Borough Council Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Blaby District Council Stratford-on-Avon District Council West Lindsey District Council Shropshire Council North Kesteven District Council Wolverhampton City Council South Holland District Council Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Boston Borough Council Lichfield District Council South Kesteven District Council Stafford Borough Council Lincoln City -

Leigh Flood Storage Area Expansion Scheme Planning, Design and Access Statement August 2020

Leigh Flood Storage Area Expansion Scheme Planning, Design and Access Statement August 2020 Environment Agency i Leigh Flood Storage Area Expansion Scheme We are the Environment Agency. We protect and improve the environment and make it a better place for people and wildlife. We operate at the place where environmental change has its greatest impact on people’s lives. We reduce the risks to people and properties from flooding; make sure there is enough water for people and wildlife; protect and improve air, land and water quality and apply the environmental standards within which industry can operate. Acting to reduce climate change and helping people and wildlife adapt to its consequences are at the heart of all that we do. We cannot do this alone. We work closely with a wide range of partners including government, business, local authorities, other agencies, civil society groups and the communities we serve. Published by: Environment Agency Horizon house, Deanery Road Bristol BS1 5AH Email: enquiries@environment- agency.gov.uk www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency 2011 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency ii Quality Assurance Project name Leigh FSA Expansion Scheme Project 1B1S reference Date 26th August 2020 Version number 01 Author Della Adams Approvals Name Signature Title Date Version Jon Walton JBA Consulting Project 24/08/2020 01 Manager Leigh FSA Expansion Scheme Planning, Design & Access Statement iii Summary The Leigh Flood Storage Area (FSA) situated approximately 3km west of Tonbridge in Kent was constructed in 1982 and currently reduces flood risk from the River Medway to properties in Tonbridge. -

Oldbury and Seal Chart SSSI Designation

COUNTY: KENT SITE NAME: OLDBURY AND SEAL CHART DISTRICTS: TONBRIDGE AND MALLING; SEVENOAKS Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 as amended. Local Planning Authorities: Tonbridge and Malling District Council, Sevenoaks District Council National Grid Reference: TQ 571558 Area: 173.93 (ha.) 429.77 (ac.) Ordnance Survey Sheet 1:50,000: 188 1:10,000: TQ 188 Date Notified (Under 1949 Act): 1951 Date of Last Revision: 1981 Date Notified (Under 1981 Act): 1990 Other Information: The site lies within the Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Part of the site is owned by the National Trust. The boundary has been amended at renotification by several extensions and deletions. Description: This site lies on the Lower Greensand ridge to the east of Sevenoaks. It contains acidic sessile oak woodland of ancient origin, more typical of northern and western Britain, together with relict heathland communities and more recently-derived secondary woodland. An outstanding assemblage of fungi is present, numbering over 250 species and including several that are rare* or scarce** in Britain. Characteristic communities of invertebrates and bryophytes (mosses and liverworts also occur. Most of the woodland on the Lower Greensand in Kent is of recent secondary origin, often having developed over former heathland. The fact that much of the woodland on this site is ancient makes it of particular interest. The composition of the woodland varies considerably: towards the north and east of the site sessile oak Quercus petraea coppice is widespread with beech Fagus sylvatica and sessile oak standards. -

Transport, Travel and Leisure Sevenoaks.Pdf

Transport, travel and leisure in Sevenoaks District Amended August 2021 This local information pack covers: information and advice about transport, travel and leisure passport photos a list of door-to-door transport schemes shopping trips help with travel costs public transport driving and parking holidays, outings and parties books, newspapers and reading campaigning for older people's rights computer tuition, technology and the Internet scams employment learning disabilities social activities Details are subject to change, please check with the organisation concerned. If you cannot find what you are looking for please contact us as we may be able to help further. Amendments and additions are also welcome. We publish other local information packs covering: Care agencies Care homes Health and wellbeing Help at home Housing Legal advice and power of attorney Memory loss and dementia Money matters Social activities Age UK Sevenoaks & Tonbridge is a registered charity no. 1088213 Tel: 01732 454108. Web: www.ageuksevenoaksandtonbridge.org.uk 1 Contents Information and advice......................................................................................................... 4 Passport Photos .................................................................................................................. 4 Door-to-Door transport schemes ......................................................................................... 4 Other transport schemes (not door-to-door) ....................................................................... -

Retail 3 Church Street, Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 5BD Floor Area

Chartered Surveyors · Commercial Agency To Let: Retail 3 Church Street, Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 5BD Floor Area: 38.51 sq m (415 sq ft) Ground Floor lock up shop situated within an attractive parade of retail units in Edenbridge town centre. EPC Rating E. Lingfield 0800 043 0136 To Let: £7,000 per annum howardcundey.com 3 Church Street, Edenbridge, Kent, TN8 5BD LOCATION ENERGY PERFORMANCE CERTIFICATE Situated to the eastern side off the High Street in Church Street. Edenbridge has a traditional High Street with a mixture of multiple and local shops, including a Waitrose Supermarket. There is significant growth planned of new residential homes. Edenbridge is advantageously located and the towns of Tunbridge Wells, Sevenoaks and East Grinstead are all within close travelling distance. The motorway network can be accessed via junction 6 M25 (Godstone) or junction 10 M23 (Crawley), both a car journey of approximately 30 minutes from the town. The international airport of London Gatwick is a similar distance from the subject property. PREMISES A ground floor lock up shop with large glazed frontage in a two storey building forming part of a retail parade with Tudor style upper elevations beneath a pitched and tiled roof. Parking is on street in bays or in the two car parks located centrally within the town. ACCOMMODATION A mainly open plan retail unit with, sink at the back of the shop and toilet facility and kitchenette to the rear. There is a separate, externally accessed store at the rear of the property. The property benefits from a suspended ceiling with Category II lighting, gas central heating and an air conditioning cassette.