Compensation for Orang Ash Native Land in Malaysia: the Perceptions and Challenges in Its Quantification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

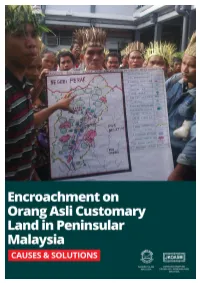

2016-SAM-JKOASM-Encroachment-On-Orang-Asli-Customary-Land-2.Pdf

All rights reserved. Reproduction or dissemination in parts or whole of any information contained in the publication is permitted for educational or other non-commercial use, under the condition that full references are made to the publication title, year of publication and copyright owners of the publication. Published by Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) and Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia (JKOASM) Sahabat Alam Malaysia 258, Jalan Air Itam 10460 George Town Penang, Malaysia Tel/Fax: +60 4 228 6930/2 Lot 129A, First Floor Jalan Tuanku Taha PO BOX 216 98058 Marudi Baram, Sarawak, Malaysia Tel/Fax: +60 85 756 973 Email: SAM[at]foe-malaysia.org Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia 39, Jalan Satu Taman Batang Padang 35500 Bidor Perak, Malaysia. Tel:+ +60 5 434 8160 All rights reserved © 2016 Sahabat Alam Malaysia and Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia This publication was made possible with financial support from the European Union. The views expressed in this publication are those of Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) and Jaringan Kampung Orang Asli Semenanjung Malaysia (JKOASM). They do not necessarily represent the position and views of the European Union. Contents List of tables iii List of abbreviations and acronyms v Glossary of non-English terms vii 1. Introduction 2 2. Statutory laws and the Orang Asli customary land rights 10 3. Illegal logging versus destructive logging 42 4. Case study: Causes of encroachment on Orang Asli customary territories 56 5. Recommendations 80 Annex: Findings of the case study on the encroachment on Orang Asli customary territories in Peninsular Malaysia 1. Pos Balar, Gua Musang, Kelantan 95 2. -

KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR & ORS V. SAGONG TASI & ORS

Kerajaan Negeri Selangor & Ors v. [2005] 4 CLJ Sagong Tasi & Ors 169 KERAJAAN NEGERI SELANGOR & ORS a v. SAGONG TASI & ORS COURT OF APPEAL, PUTRAJAYA b GOPAL SRI RAM JCA ARIFIN ZAKARIA JCA NIK HASHIM JCA [CIVIL APPEAL NO: B-02-419-2002] 19 SEPTEMBER 2005 c LAND LAW: Acquisition of land - Compensation - Customary land - Whether plaintiffs held land under customary communal title - Whether plaintiffs entitled to compensation for deprivation of gazetted and ungazetted land - Whether plaintiffs entitled to recover damages for trespass from defendants - Whether exemplary damages ought to be d awarded to plaintiffs LAND LAW: Customary land - Proof of custom - Whether established - Whether plaintiffs entitled to compensation for deprivation of gazetted and ungazetted land - Whether plaintiffs entitled to recover damages for e trespass from defendants - Whether exemplary damages ought to be awarded to plaintiffs NATIVE LAW AND CUSTOM: Land dispute - Customary rights over land - Whether plaintiffs held land under customary communal title - Whether plaintiffs entitled to compensation for deprivation of gazetted and f ungazetted land - Whether plaintiffs entitled to recover damages for trespass from defendants - Whether exemplary damages ought to be awarded to plaintiffs LAND LAW: Trespass - Damages - Whether plaintiffs entitled to recover damages for trespass from defendants - Whether second and third g defendants entered onto land without consent - Whether exemplary damages ought to be awarded to plaintiffs TORT: Damages - Trespass to land - Assessment of damages - Whether exemplary damages ought to be awarded h i CLJ 170 Current Law Journal [2005] 4 CLJ a These were four appeals by the four defendants against the judgment of the High Court granting the plaintiffs compensation under the Land Acquisition Act 1960 (‘the 1960 Act’) for the loss of certain land which the judge found to have been held under customary title. -

Faculty of Law, University of Malaya Constitutional Law Lecture Series

Faculty of Law, University of Malaya Constitutional Law Lecture Series Protection of Marginalised Minorities Under The Constitution By Dato’ Seri Mohd Hishamudin Yunus Retired Court of Appeal Judge Consultant, Messrs. Lee Hishammuddin Allen & Gledhill 1 Distinguished Audience, Ladies and Gentleman, Good evening, It is truly an honour to be invited by the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya, to deliver a Constitutional law lecture in this pleasant evening. I must thank and congratulate Dr. Johan, Dean of the Faculty and Messrs Chooi & Company for jointly organizing this Constitutional law lecture series, which is very beneficial to law students and the general public. Introduction The topic of today’s lecture is “Protection of Marginalised Minorities Under the Constitution” There are two elements in today’s topic: on one hand we have the “Federal Constitution”; and on the other hand, we have “marginalised minorities”. I shall begin by referring to a basic principle of constitutional law that many members of the audience are familiar with: the principle of the supremacy of the Constitution. This principle stipulates that no one institution is supreme; not even Parliament. Only the Federal Constitution is supreme, being the highest law of the country. It binds both state and federal governments, including the executive branch. In other words, the organs of Government must operate in accordance with what is prescribed or empowered by the Federal Constitution; they must not transgress any Constitutional provisions. Now, the phrase “marginalised minorities” is not defined in our Constitution; and therefore, I look into dictionaries for guidance. The Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern 2 English published by Oxford shed some light in this regard. -

Finally... RM6.5Mil Compensation for Orang Asli Malaysiakini.Com May 26, 2010 Hafiz Yatim

Finally... RM6.5mil compensation for Orang Asli Malaysiakini.com May 26, 2010 Hafiz Yatim After a 15-year legal battle, 26 families of a Temuan tribe in Selangor have obtained RM6.5 million in compensation for their native customary land which was seized to build a highway to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA). sagong tasi bukit tampoi case 090107 explainSagong Tasi, 78 (left), and six others - two of whom have since died - had filed a suit against the federal government, the then BN-led Selangor government, Malaysian Highway Authority (MHA) and contractor United Engineers Malaysia Bhd (UEM). This was after their land was acquired without compensation to build the Nilai-Banting highway that also runs to KLIA in Sepang in January 1995. The landmark settlement made by the Federal Court this morning also has the effect of recognising the native customary rights of these Orang Asli to the 38-acre site of their former settlement in Bukit Tampoi, Dengkil. Chief Judge of Malaya Arifin Zakaria, Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak Richard Malanjum and James Foong, who made up the three-member bench, ordered the sum to be deposited with the Shah Alam High Court within a month from today. Senior federal counsel Kamaluddin Md Said - who was assisted by senior federal counsel Saifuddin Edris Zainuddin representing the federal government - said the other two parties, MHA and UEM, have agreed to withdraw their appeal over the Court of Appeal decision. NONE“We want the court to record settlement by both parties,” he said. UEM was represented by Harjinder Kaur. -

Legal Analysis to Assess the Impact of Laws, Policies and In

LEGAL ANALYSIS TO ASSESS THE IM PACT OF LAWS, POLICIES AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND COMMUNITY CONSERVED TERRITORIES AND AREAS (ICCAS) IN MALAYSIA T h e G l o b a l S u p p o r t I n i t i a t i v e t o I n d i g e n o u s P e o p l e s a n d C o m m u n i t y - C o n s e r v e d T e r r i t o r i e s a n d A r e a s ( I C C A - G S I ) i s f u n d e d b y t h e G o v e r n m e n t o f G e r m a n y , t h r o u g h i t s F e d e r a l M i n i s t r y f o r t h e E n v i r o n m e n t , N a t u r e C o n s e r v a t i o n a n d N u c l e a r S a f e t y ( B M U ) , i m p l e m e n t e d b y t h e U n i t e d N a t i o n s D e v e l o p m e n t P r o g r a m m e ( U N D P ) a n d d e l i v e r e d b y t h e G E F S m a l l G r a n t s P r o g r a m m e ( S G P ) . -

Orang Asli Land Rights by Undrip Standards in Peninsular Malaysia: an Evaluation and Possible Reform

ORANG ASLI LAND RIGHTS BY UNDRIP STANDARDS IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA: AN EVALUATION AND POSSIBLE REFORM YOGESWARAN SUBRAMANIAM A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales Faculty of Law August 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Subramaniam First name: Yogeswaran Other name/s: NIL Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Law Faculty: Law Title: Orang Asli land rights by UNDRIP standards in Peninsular Malaysia: an evaluation and possible reform Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis makes an original contribution to knowledge by evaluating Malaysian laws on Orang Asli (‘OA’) land and resource rights and suggesting an alternative legal framework for better recognition and protection of these rights: (1) by reference to standards derived from the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (‘UNDRIP’); and (2) having regard to the Malaysian Constitution. Malaysia’s vote supporting the UNDRIP and its courts’ recognition of common law Indigenous customary land rights have not induced state action that effectively recognises the customary lands of its Indigenous minority, the OA people. Instead, state land policies focus on the advancement of OA, a marginalised community, through development of OA lands for productive economic use. Such policies may have some positive features but they also continue to erode OA customary lands. Existing protectionist laws affecting OA facilitate these policies and provide limited protection for OA customary lands. Resulting objections from the OA community have prompted calls to honour the UNDRIP. -

PDF Download Property and Politics in Sabah, Malaysia

PROPERTY AND POLITICS IN SABAH, MALAYSIA : NATIVE STRUGGLES OVER LAND RIGHTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amity A. Doolittle | 232 pages | 17 Aug 2005 | University of Washington Press | 9780295985398 | English | Seattle, United States Property and Politics in Sabah, Malaysia : Native Struggles Over Land Rights PDF Book This is our Adat land, our ancestors' land. Despite their cultural differences, indigenous peoples from around the world share common problems related to the protection of their rights as distinct peoples. Harwell; 7. Previously rubber had come from scattered trees growing wild in the jungles of South America with production only expandable at rising marginal costs. The driving force came from the Industrial Revolution in the West which saw the innovation of large scale factory production of manufactured goods made possible by technological advances, accompanied by more efficient communications e. In , shortly after a Malaysian politician announced that the boundaries of Kinabalu Park, a primary tourist destination, were to be expanded to include the species-rich tropical forest known locally as Bukit Hempuen, most of the area was burned to the ground, allegedly by local people. This new form permits a formulation of Orang Asli citizenship that does not limit them to claiming rights as "wards," binding them to a paternalistic relationship to the state. British estates depended mainly on migrants from India, brought in under government auspices with fares paid and accommodation provided. Average values fell thereafter but investors were heavily committed and planting continued also in the neighboring Netherlands Indies [Indonesia]. Furnivall described as a plural society in which the different racial groups live side by side under a single political administration but, apart from economic transactions, do not interact with each other either socially or culturally. -

Federal and State Jurisdictions Dr

STRENGTHENING CAPACITY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL LAW IN MALAYSIA’S JUDICIARY: TRAIN-THE-JUDGES PROGRAM (TTJ) 10 - 13 JULY 2017 ILKAP, BANGI, Malaysia PRESENTATION: FEDERAL AND STATE JURISDICTIONS DR. NORMAWATI BINTI HASHIM PROF. MADYA NORHA ABU HANIFAH ELF MEMBER FEDERAL CONSTITUTION NINTH SCHEDULE (Articles 74,77) LEGISLATIVE LIST LIST II STATE LIST LIST III LIST 1 LIST IIA CONCURRENT FEDERAL LIST SUPLEMENT TO STATE LIST SABAH SARAWAK ARTICLE 77 RESIDUAL POWER Relevant areas on environment - Treaties, agreements and conventions with other Federal countries List - Trade, commerce and industry - Development of mineral resources, mines, mining, minerals, factories, fisheries, maritime Relevant areas on environment Federal - Communication, transport List - Federal works and power - Water supplies, rivers, canals except those within one state Relevant areas on environment Federal - Electricity List - Gas and gas works -Welfare of aborigines State List Land tenure Permits and licenses for prospecting for mines Agriculture and forestry State List ! Local government outside Federal territories Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, Labuan, including obnoxious trades and public nuisances in local authority areas ! Water (excluding water supplies), rivers, canals ! Control silt, riparian rights ! Turtles ! Riverine fishing ! Islamic Law Concurrent List Animal husbandry Town and country planning except in the federal capital Public health, sanitation (excluding sanitation in federal capital), prevention of diseases Concurrent List Drainage, irrigation Protection of wild animals, wild birds National parks Concurrent List Prevention of cruelty to animals Veterinary services Animal quarantine Concurrent List Rehabilitation of mining land which has suffered soil erosion (Subject to Federal list) water supplies and services Conflict of jurisdictions between Federal and State • Art. 75 states if state law is inconsistent with the Federal law, and State Law is void to the extend of its inconsistency. -

Recognizing Indigenous Identity in Postcolonial Malaysian Law : Rights and Realities for the Orang Asli (Aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia

This is a repository copy of Recognizing indigenous identity in postcolonial Malaysian law : rights and realities for the Orang Asli (aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79092/ Version: Published Version Article: Nah, Alice M. orcid.org/0000-0002-0253-0334 (2008) Recognizing indigenous identity in postcolonial Malaysian law : rights and realities for the Orang Asli (aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia. Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia,. pp. 212-237. ISSN 2213-4379 https://doi.org/10.1163/22134379-90003657 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ALICE M. NAH Recognizing indigenous identity in postcolonial Malaysian law Rights and realities for the Orang Asli (aborigines) of Peninsular Malaysia Introduction In Southeast Asia, the birth of postcolonial states in the aftermath of the Sec- ond World War marked a watershed in political relations between ethnic groups residing within emerging geo-political borders.1 Plurality and dif- ference were defining characteristics of the social landscape in these nascent states. -

The Pakatan Rakyat Selangor State Administration: Present and Future Challenges on the Road to Reform

The Round Table ISSN: 0035-8533 (Print) 1474-029X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctrt20 The Pakatan Rakyat Selangor State Administration: Present and Future Challenges on the Road to Reform Tricia Yeoh To cite this article: Tricia Yeoh (2010) The Pakatan Rakyat Selangor State Administration: Present and Future Challenges on the Road to Reform, The Round Table, 99:407, 177-193, DOI: 10.1080/00358531003656347 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00358531003656347 Published online: 01 Apr 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 88 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctrt20 Download by: [Columbia University Libraries] Date: 02 February 2017, At: 11:43 The Round Table Vol. 99, No. 407, 177–193, April 2010 The Pakatan Rakyat Selangor State Administration: Present and Future Challenges on the Road to Reform TRICIA YEOH Centre for Public Policy Studies, Asian Strategy and Leadership Institute, Kuala Lumpur ABSTRACT Dubbed the ‘political tsunami’, the 8 March 2008 elections in Malaysia gave overwhelming results. Selangor is one of the five states now governed by the Pakatan Rakyat coalition. This was a significant win, being the most urban and lucrative state of the country. It has been considered a model state for the Pakatan Rakyat in its desire to position itself as an alternative federal government. This has been the mandate of the new Selangor government, but its execution has been accompanied by numerous obstacles. This paper analyses the distinctive reform measures undertaken by the state government, the challenges faced, ensuing political transformation, and long-term prospects for Pakatan Rakyat in Selangor. -

Pacific Rim Property Research Journal

DEVELOPING A COMPENSATION FRAMEWORK FOR THE ACQUISITION OF ORANG ASLI NATIVE LANDS IN MALAYSIA: THE PROFESSIONALS’ PERCEPTIONS ANUAR ALIAS and MD NASIR DAUD University of Malaya ABSTRACT This research explores the issues of land rights and land acquisition compensation related to the Orang Asli (the Malay term for indigenous peoples) in Peninsular Malaysia. Acquisition of Orang Asli native lands is inevitable as land is scarce to meet the national growth agenda and socio-economic developments. As an independent country, Malaysia provides constitutional guarantees, and customary land tenure is recognised and respected. Unfortunately, due to the ambiguity in Malaysian legal system in relation to the definition of land rights of Orang Asli native lands, the practice of payment of compensation to acquisition of the land tends to be unstructured, and disparity exists among the different states. It is therefore pertinent to propose a uniform compensation framework for the acquisition of Orang Asli native lands. This research adopts a questionnaire survey as the method of study, the descriptive and inferential analysis technique to present the results. The study showed that laws of Malaysia are deficient with regard to the protection of Orang Asli lands and rights to fair and just compensation. This research found that the position of Orang Asli land rights has not improved much. Due to this unresolved land rights issue, the present structure of compensation as spelt out under Sections 11 and 12 of the Aboriginal Peoples Act 1954 is perceived as inadequate. As currently practised, in the absence of proper guidelines and regulations, the determination of compensation is entirely at the discretion of the various authorities. -

Download Publication

IWGIA THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2010 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2010 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD This yearbook contains a comprehensive update on the current situation of indigenous peoples and their human rights, and provides an overview of the most important developments in international and regional processes during 2009. 72 indigenous and non-indigenous scholars and activists provide their insight and knowledge to the book with: Region and country reports covering most of the indigenous world. Updated information on international and regional processes relating to indigenous peoples. The Indigenous World 2010 is an essential source of information and indispensable tool for those who need to be informed about the most recent issues and developments that have impacted on indige- nous peoples worldwide. It is published in English and Spanish. 2010 INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2010 Copenhagen 2010 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2010 Compilation and editing: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Regional editors: The Circumpolar North & North America: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Asia: Christian Erni and Christina Nilsson The Middle East: Diana Vinding Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen and Geneviève Rose International Processes: Lola García-Alix and Cæcilie Mikkelsen Cover and typesetting: Jorge Monrás Maps: Ronan McHugh and Jorge Monrás English translation: Elaine Bolton and Brenda Gonzalez Proof reading: Elaine Bolton Russian translation: Jennifer Castner Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark © The authors and The International Work HURRIDOCS CIP data Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), 2010 - All Rights Reserved Title: The Indigenous World 2010 Edited by: Cæcilie Mikkelsen Pages: 632 The reproduction and distribution of informa- ISSN: 1024-0217 tion contained in The Indigenous World is wel- ISBN: 978-87-91563-75-1 come as long as the source is cited.