Karen Fellenz Mcnamara, MSW, LCSW-C Date

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eli J. Finkel – Curriculum Vitae (September, 2021)

Eli J. Finkel – Curriculum Vitae (September, 2021) Professional Information Mail: Northwestern University Northwestern University Department of Psychology Kellogg School of Management Swift Hall, Room 102 Department of Management and Organizations 2029 Sheridan Road 2211 Campus Drive Evanston, IL 60208 Evanston, IL 60208 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Numbers: Phone: 847-491-3212 / Fax: 847-491-7859 Phone: 847-491-8672 / Fax: 847-491-8896 Website: http://elifinkel.com ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0213-5318 Education Ph.D., 2001 Social & Quantitative Psych University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Mentor: Caryl E. Rusbult) M.A., 1999 Social & Quantitative Psych University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Mentor: Caryl E. Rusbult) B.A., 1997 Psychology Northwestern University (Mentors: J. Michael Bailey and Neal J. Roese) Professional Experience Primary Appointments 2013– Professor of Management and Organizations, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University 2012– Professor of Psychology, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University 2008–2012 Associate Professor of Psychology, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University 2003–2008 Assistant Professor of Psychology, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University Additional Appointments 2019 Visiting Scholar, Department of Social Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam 2008 Visiting Scholar, Department of Social Psychology, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam 2007– Faculty Associate, Institute -

University of South Florida Libraries Holocaust & Genocide Studies Draft

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special & Digital Collections Faculty and Staff Special & Digital Collections Publications 12-1-2008 University of South Florida Libraries Holocaust & Genocide Studies Draft uB siness Plan Mark I. Greenberg University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tlsdc Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Greenberg, Mark I., "University of South Florida Libraries Holocaust & Genocide Studies Draft usineB ss Plan" (2008). Special & Digital Collections Faculty and Staff Publications. Paper 4. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/tlsdc/4 This Business Plan is brought to you for free and open access by the Special & Digital Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special & Digital Collections Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA LIBRARIES HOLOCAUST & GENOCIDE STUDIES CENTER DRAFT BUSINESS PLAN JULY 25, 2008 REV. DEC. 1, 2008 AUTHOR: MARK I. GREENBERG, MLS, PH.D. DIRECTOR, SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA TAMPA LIBRARY “There can be no more important issue, and no more binding obligation, than the prevention of genocide.” United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan (January 26, 2004) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Genocide and mass violence have become global threats to peace and security and a sad testament to the human condition. Almost a half million genocide and torture victims currently reside in the United States, with millions more suffering silently in other parts of the world. -

2019 Media Guide 2019 Media Guide

2019 MASTERS MEDIA GUIDE 2019 MEDIA GUIDE 2019 MEDIA GUIDE masters.com | April 8-14 | @TheMasters Printed on Recycled Paper Fred S. Ridley Chairman Joe T. Ford Vice Chairman James B. Hyler, Jr. Chairman, Competition Committees Media Committee: The Media Committee is dedicated to providing the press with the best tools and working environment possible. The Masters Tournament staff is available to assist the media, when possible, during the week of the Tournament and throughout the year. Craig Heatley Chairman, Media Committee For more information, please contact: Steven P. Ethun Director of Communications (706) 667-6705 - Direct (706) 832-1352 - Mobile e-mail: [email protected] Address: Post Office Box 2047 2604 Washington Road Augusta, GA 30903 Augusta, GA 30904 Telephone: (706) 667-6000 Website: masters.com Social Media: Twitter: @TheMasters Instagram: @TheMasters Facebook: facebook.com/TheMasters On the Cover: No. 12, Golden Bell Not for Resale For Media Use Only ©2019 by Augusta National, Inc. The 2019 Masters Media Guide is published for use by the media. Permission is hereby granted for excerpts from this work to be used in articles written for newspapers, magazines and the internet and for television and radio reports. Photographs and other pictorial material, and Masters or Augusta National Golf Club logos, may not be reprinted or reused without the express written permission of Augusta National, Inc. All other rights reserved. • Masters Electronic Device Policy: Electronic devices (including phones, laptops, tablets, and beepers) are strictly prohibited on the grounds at all times. Any device being used to record and/or transmit voice, video, or data is strictly prohibited. -

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA BOO KK Class 2021-3 19

BBIIOOGGRRAAPPHHIICCAALL DDAATTAA BBOOOOKK Class 2021-3 19 Apr - 7 May 2021 National Defense University NDU PRESIDENT Lieutenant General Mike Plehn is the 17th President of the National Defense University. As President of NDU, he oversees its five component colleges that offer graduate-level degrees and certifications in joint professional military education to over 2,000 U.S. military officers, civilian government officials, international military officers and industry partners annually. Raised in an Army family, he graduated from Miami Southridge Senior High School in 1983 and attended the U.S. Air Force Academy Preparatory School in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy with Military Distinction and a degree in Astronautical Engineering in 1988. He is a Distinguished Graduate of Squadron Officer School as well as the College of Naval Command and Staff, where he received a Master’s Degree with Highest Distinction in National Security and Strategic Studies. He also holds a Master of Airpower Art and Science degree from the School of Advanced Airpower Studies, as well as a Master of Aerospace Science degree from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. Lt Gen Plehn has extensive experience in joint, interagency, and special operations, including: Middle East Policy in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization, and four tours at the Combatant Command level to include U.S. European Command, U.S. Central Command, and twice at U.S. Southern Command, where he was most recently the Military Deputy Commander. He also served on the Air Staff in Strategy and Policy and as the speechwriter to the Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force. -

Maccabiah Games Australia's Maccabeans

AUSTRALIA’S MACCABEANS OUR ROLL OF HONOUR 3rd MACCABIAH GAMES, 1950 to 18th MACCABIAH GAMES, 2009 1. AARON, CLIVE 2009 MASTERS SWIMMING 2. AARONS, GARY 1997 RUGBY 3. AARONS,ANTHONY 2005 TENPIN BOWLING, 2009 TENPIN BOWLING 4. AARONS,ELLANA 2005 OFFICIAL, 2009 OFFICIAL 5. AARONS, LISA 1985 HOCKEY 6. AARONS, LUKE 1997 GOLF 7. ABADEE, LEAH 1985 LAWN BOWLS 8. ABELMAN, MICHAEL 1981 HOCKEY 9. ABISEDON, BENJAMIN 2005 JUNIOR KARATE 10. ABKIN, BARRY 2009 TRIATHON 11. ABRAMS, GARY 2009 MASTERS TENNIS 12. ABRAMS, MARC 2009 JUNIOR BASKETBALL 13. ABRAHAMS, DIANE 1993 NETBALL 14. ABRAHAMS, RICK 1993 GOLF, 1997 MASTERS GOLF 15. ABRAHAMS, RYAN 2005 FOOTBALL 16. ABRAMOVICH, DAVID 1957 ATHLETICS 17. ABZATZ, DAVID 1989 HOCKEY 18. ADAMS, ALAN 1981 YACHTING 19. ADELMAN, SAMI-JO 2009 FOOTBALL 20. ADELSTEIN, GEOFF 1973 ATHLETICS 21. ADLER, GEORGE 1977 SOCCER; 1981 OFFICIAL 22. ADONIS, DANIEL 2009 CRICKET 23. ADONIS, DAVID 2009 CRICKET 24. ADONIS, MARC 1977, 1985, 1989, 1993,1997 OFFICIAL 25. ADONIS, SIMON 1993 FOOTBALL 26. AHARONI, NATHAN 1993 FOOTBALL 27. AKERSTEIN, DAVID 1989 TENPIN BOWLING 28. AKRES, JEFFREY 2005 MASTERS’ FOOTBALL 29. ALBERT, MICHELLE 2005 KARATE 30. ALEKSEEVA, LARISA 2005 MASTERS’ TENNIS 31. ALEXANDER, FREDERICK 1993 LAWN BOWLS 32. ALLEN, GEOFFREY 2005 RUGBY 33. ALLEN, JOSHUA 2009 RUGBY 34. ALLEN, PETER 1977 ATHLETICS 35. ALLEN, SALLY 1997 OFFICIAL 36. ALPERSTEIN, DAVID 1985, 1989, 1993,1997,2005,2009 MASTERS’ SQUASH 37. ALT, ALEXANDER 1993 KARATE 38. ALTMAN, HENRY 1977 WEIGHTLIFTING 39. AMPER, PAUL 1985 OFFICIAL 40. ANTMAN, PHILIP 1973 CRICKET 41. ANTMAN, TONY 1985 RUGBY 42. APPLE, AMANDA 1989, 1993 ATHLETICS,1997 OFFICIAL 43. -

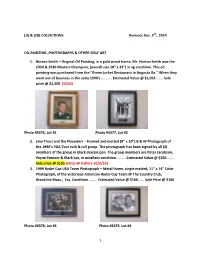

COLLECTIONS Revised; Dec. 5Th, 2014

(JJ) & (CB) COLLECTIONS Revised; Dec. 5th, 2014 OIL PAINTING, PHOTOGRAPHS & OTHER GOLF ART 1. Horton Smith – Original Oil Painting, in a gold wood frame, Mr. Horton Smith was the 1934 & 1936 Masters Champion, (overall size 18” x 22”) in vg condition. This oil painting was purchased from the “Green Jacket Restaurant in Augusta Ga.” When they went out of business in the early 1990’s ……….. Estimated Value @ $1,995 ……. Sale price @ $1,500 (SOLD) Photo #3376, Lot #1 Photo #3377, Lot #2 2. Jake Trout and the Flounders – Framed and matted (8” x 10”) B & W Photograph of the 1990’s PGA Tour rock & roll group. The photograph has been signed by all (3) members of the group in black sharpie pen. The group members are Peter Jacobson, Payne Stewart & Mark Lye, in excellent condition. …….. Estimated Value @ $250……… Sale price @ $195 (SOLD @ Gallery 10/9/14) 3. 1999 Ryder Cup USA Team Photograph – Metal frame, single matted, 11” x 14” Color Photograph, of the victorious American Ryder Cup Team @ The Country Club, Brookline Mass., Exc. Condition ……… Estimated Value @ $160 …… Sale Price @ $100 Photo #3378, Lot #3 Photo #3379, Lot #4 1 4. Jack Nicklaus & Arnold Palmer – Wood framed, double matted 11” x 14” B & W Photograph of Jack Nicklaus & Arnold Palmer, circa 1960’s, in excellent condition. Estimated Value @ $160 ……… Sale price @ $100 5. Tommy Aaron – Wood framed, double matted, collage of Tommy Aaron the 1973 Masters Champion, autographed 3 x 5 unlined index card, 6” x 8” photograph of Mr. Aaron, his 1981 Masters Contestant bag tag, 11” x 14” color photograph of the 13th green with an engraved plate, all in excellent condition, over-all size (24” x 32”) a beautiful collection professionally framed etc. -

Andy Segal's Cue Magic

Andy Segal’s Cue Magic Inside the World of Modern Trick Shots By Andy Segal Copyright ©2013 By Andy Segal Published by: Billiards Press New York, NY First Printing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or by an information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of quotations in a review. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Control Number 2013951700 ISBN 978-0-9898917-0-7 Cover design and diagrams by Janet Tedesco Illustrations by Lorelei Arts, Nicholas Eriksen, Maritza Ortiz Photos by Michael Pollan Proofreading by Barbara Berkowitz, Kim Segal Elevation Measurements by Jessica Segal viii Part I – Getting Started Part II – Cue Magic 1: Introduction ............................................3 6: Bank/Kick Shots ................................45 6.1: Compression Kick Back #1 ...............46 2: Terminology & Conventions ...........7 6.2: Compression Kick Back #2 ...............47 2.1: The Rails ..................................................8 6.3: 5-Rail Chain Reaction ..........................48 2.2: The Pocket ..............................................8 6.4: The Slider ..............................................49 2.2.1: Hanging a Ball .........................................9 6.5: Pinball ....................................................50 2.3: Frozen Balls .............................................9